By Contributing Editor Yitzchak Schwartz

In 1946, the artist and illuminator Arthur Szyk presented First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt with a signed portrait of her husband. Dated 1944, before the war had been won, the portrait depicts Roosevelt looming triumphant over his fascist enemies. It is inscribed, “To Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt from Arthur Szyk, F.D.R.’s soldier in art.” This portrait is one of the highlights and the namesake of the exhibition Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art, running through January 21st at the New York Historical Society.

In his day, Szyk (pronounced Schick) was most famous for his political art. During WWII he created countless political cartoons and political cover art for Collier’s, Time and the New York Times Book Review. According to Szyk scholar Allison Claire Chang, more than 25 exhibitions of Szyk’s anti-fascist work were held in 1941 alone to raise money for the war effort. At the height of his acclaim, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote of him in her January 8, 1943 “My Day” column that, “In its way [Szyk’s work] fights the war against Hitlerism as truly as any of us who cannot actually be on the fighting fronts today.” Recently, Szyk’s political art has been the subject of major exhibitions at the Library of Congress (1999), the United States Holocaust Museum (2002), and the Deutsches Historisches Museum (2008).

Although his political art looms large at the New York Historical Society, several of Szyk’s most profound illuminations are also on display. They are also a major point of emphasis in the exhibition catalog, Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art. The volume is edited by Irvin Ungar, the leading expert on Arthur Szyk’s art, who assembled the collection (now part of the Magnes Collection at UC Berkeley) of which many of the works featured in this exhibition are a part. It features essays by historian Michael Berenbaum, art historian James Kettlewell, art historian and President of the American Federation of Arts Tom Freudenheim, Ungar and a preface by former New York Times Art Director Steve Heller.

In the catalog, art historian James Kettlewell argues that during his career Szyk sought to elevate illumination to the status of a fine art in the modern age. His illuminations, especially when taken together with the voluminous supplementary images in the catalog, display Szyk’s astounding stylistic diversity. He often worked in several styles at any given time and combined elements of various historical and contemporary styles in the same works. In all of his mature work, however, Szyk took inspiration from historical illumination while maintaining a thoroughly modern sensibility. As former Village Voice film critic J. Hoberman notes in his review of the exhibition, Szyk’s unique style makes it hard to compare him to either contemporaries or predecessors, and his art is in many ways sui generis.

Szyk’s earliest extant works date from his teens, when he published satirical cartoons in various Polish magazines. His earliest paintings date from just after his return from art studies in Paris in 1912-1914. None of them made it into the exhibition but a few of them are featured in the catalog, intricate oriental fantasies replete with lively line and curve patterns and colorful geometric details.

Even as he created works in this vein, Szyk’s style began to shift. In 1918 a Polish-Jewish literary society sent Szyk and other artists on a tour of Palestine. There he made contacts in the Bezalel art academy, which sought to recreate a Jewish national artistic tradition in the Land of Israel. Many extant works from this period in Szyk’s career contain signature elements of that movement such as vistas of the land of Israel, themes of national redemption. and the use of Near-Eastern artistic styles and archaeological forms. In Szyk’s 1925 Book of Esther, for example, King Ahasuerus is depicted as a neo-Assyrian king, with a long, braided beard and conical helmet, a human-headed winged lion in the background. Bezalel was influential in Szyk’s work but during this same period he also evinced very different influences in other works, such as his 1926 surrealist-expressionist interpretation of Flaubert’s La Tentation de saint Antoine.

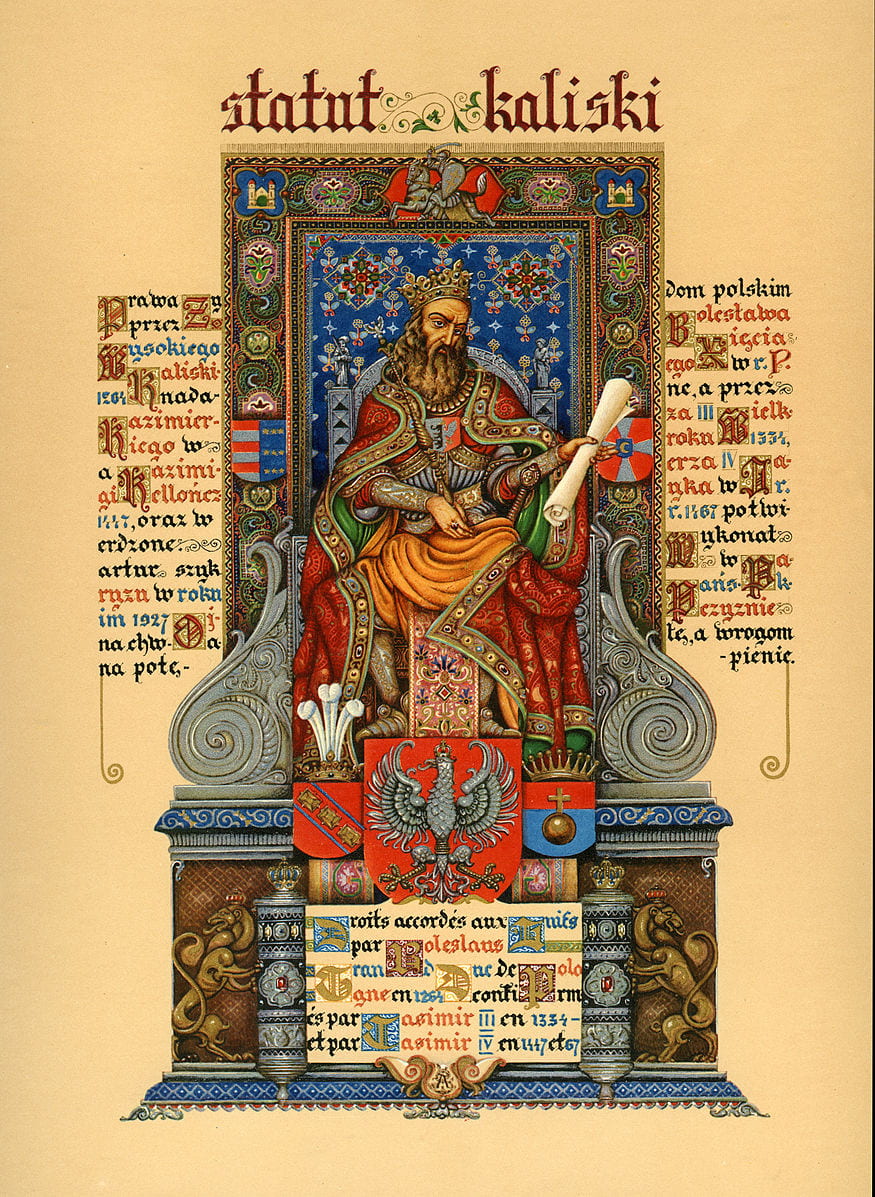

In 1929, Szyk exhibited his forty-five page illuminated Statute of Kalisz, a charter granted to Jews for settlement by the Duke of Kalisz in 1264, in Warsaw, Lodz and Kalisz. Szyk received the Gold Cross of Merit from the Polish government in recognition of the work, which depicts vignettes of Polish-Jewish history and Jewish contributions to Poland. Its title page features the Polish King Casmir III the Great enthroned above the statue itself, which resembles an open Torah scroll flanked by two rampant lions. The decorative program of The Statute is executed in a high Gothic idiom but many of the vignettes are unmistakably modern.

Statute of Kalisz, frontispiece (1927).

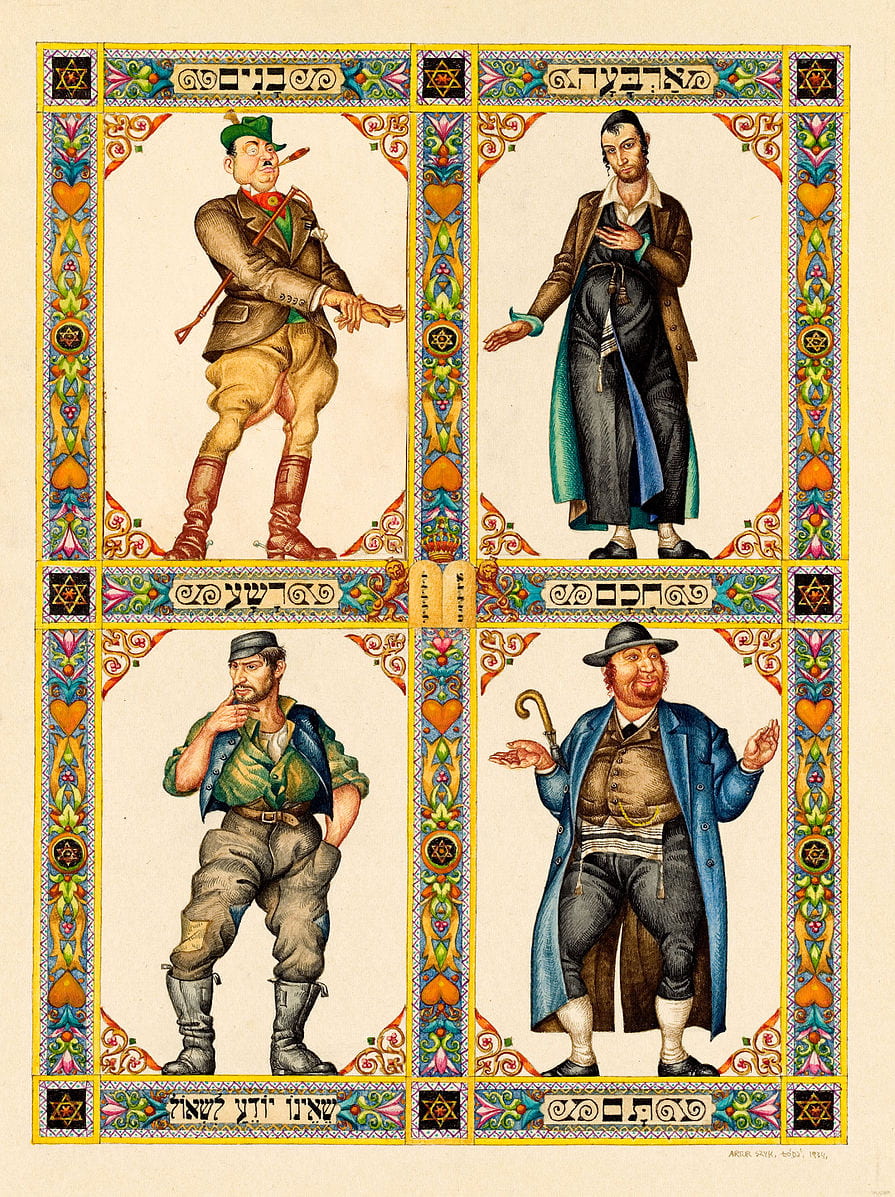

Szyk’s 1940 Haggadah, considered by many his magnum opus, evinces strong influence from medieval Jewish illumination but it is also thoroughly of his time, combining historical references with realist imagery. Szyk’s depiction of the four sons follows a medieval and early modern convention of making the sons into caricatures of contemporary types. His wise son is a classical yeshiva student, his uneducated son an Israeli Kibbutznik, his simple son a jolly hasid, and his wicked son a cigar-smoking German gentleman.

The Haggadah. The Four Sons (1934).

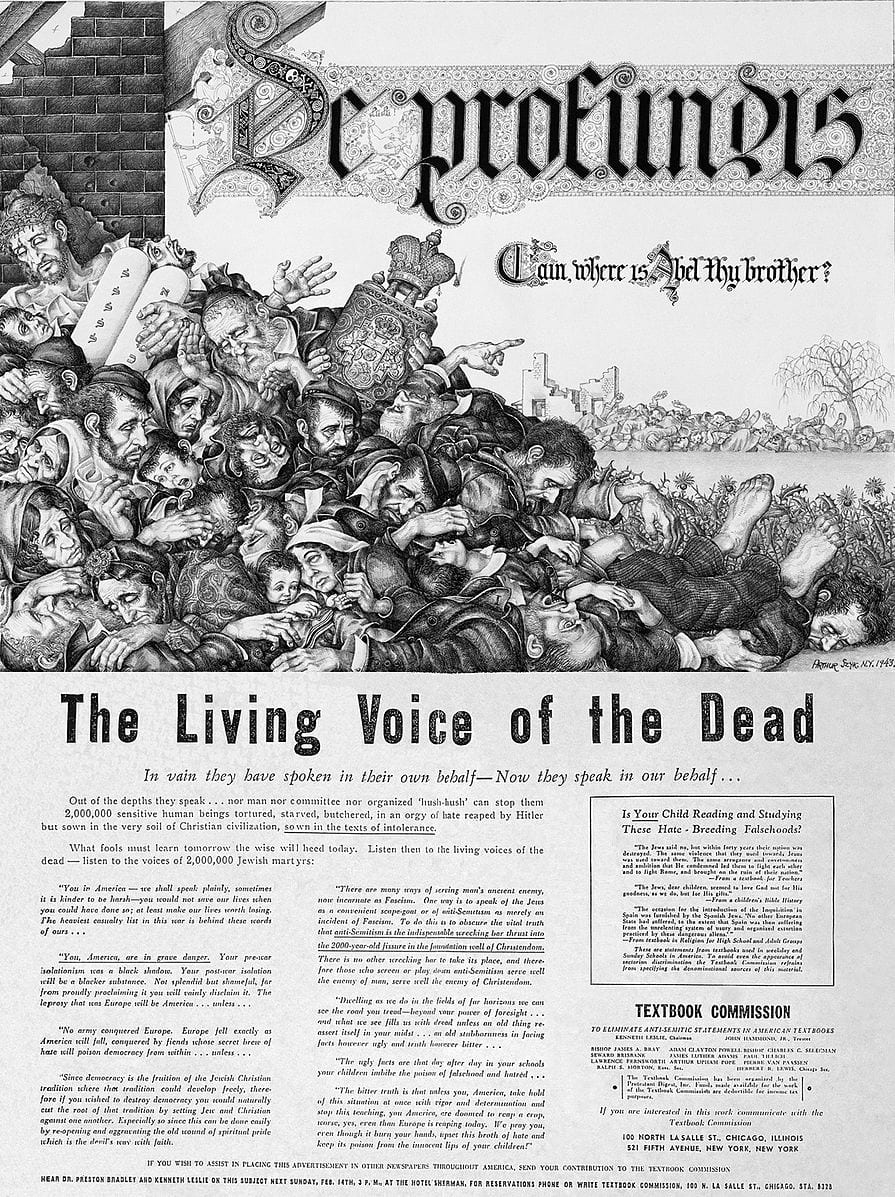

In addition to his illuminated books, several of Szyk’s political illuminations also stand out in the exhibition. Many of these are executed in a realist style very far from that of his illuminated books. One of these is a 1943 work titled De Profundis, a reference to Psalm 130. It was commissioned by the Christian Textbook Commission, an organization that aimed to excise anti-Semitism from Christian curricula. The black and white drawing depicts slaughtered Jews of varied religious and socio-economic backgrounds, Jesus with his crown of thorns among them, holding the ten commandments against his body. The caption reads, “Cain, where is Abel thy brother?” Irvin Ungar, the Szyk expert and collector, calls De Profundis Szyk’s Guernia.

De Profundis (Chicago Sun, 1943).

Szyk’s work has gained increasing popularity and scholarly attention over the past two decades as scholars have begun to explore early twentieth-century Jewish art and because of the exhibitions mentioned above. His place in American political art is increasingly well-documented but his work raises very interesting questions for historians of American Judaism, of Jewish art, and of Zionist art that remain to be explored. Thankfully, this exhibition leaves us with plenty of food for thought.

Leave a Reply