By Contributing Writer Craig Johnson

Alberto Ignacio Ezcurra Uriburu, the leader of Argentina’s first modern terrorist organization, was a frail, dark-haired, long-faced seminary dropout rarely seen without his thick black glasses. Right-wing power and ideology ran in his family. His father was Alberto Ezcurra Medrano, an important conservative jurist, who in the 1930s was a close personal friend with the fascist Spanish ambassador to Argentina. His paternal grandfather was the dictator General Uriburu, whose early 20th-century coup attempted to remake the nation into a Catholic, fascistic state. Through his mother, Ezcurra was a descendant of Argentina’s most important and influential caudillo of the 19th century, Juan Manuel de Rosas, who required everyone in Buenos Aires to wear badges with his faction’s red banner and to display his portraits in church beside the pulpit.

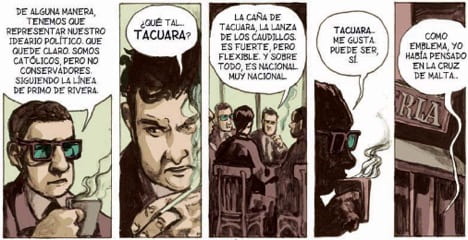

Ezcurra was well-off and had access to the highest echelons of Argentine politics and power. But in his twenties he found himself a failure. Having been forced to drop out of Jesuit seminary for his “introverted and confrontational personality” he turned to unfulfilling minor white collar work in his home of Buenos Aires. There, he drifted to the youth division of Argentina’s main right-wing political organization, the Alianza de Libertadora Nacionalista. But he didn’t stay long. One night in 1957 he and his dissolute elite friends were drinking at the hip, popular bar La Perla del Once, and, dissatisfied with the lukewarm fervor of the Alianza de Libertadora Nacionalista, decided to make a new organization: Tacuara, a knife tied to a cane, the makeshift spear Argentinian peasants had fought the English with when they invaded Argentina in 1806.

Tacuara would soon become Argentina’s first major guerilla and militant organization since the Second World War. Their symbol was to be the Maltese Cross of the crusading Knights Hospitaller. At its height in 1962-63 Tacuara boasted a membership in the thousands, spread across Argentina from Cordoba to Rosario to La Plata and in most of the country’s major universities and secondary schools. With these men Tacuara waged a campaign of violence and propaganda.

Ezcurra, standing and speaking at podium, with other members of Tacuara

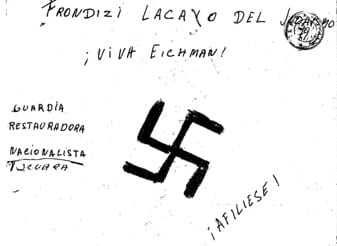

In 1960, Adolf Eichman, a Nazi official who had hid in Argentina after the Second World War, was abducted from his suburban Buenos Aires home by Mossad and taken to Israel, tried for war crimes and executed. In response Tacuaristas painted the streets of Buenos Aires with black swastikas and brutal slogans: Viva Eichman; In the future there won’t be enough furnaces for the Jews. They constantly attacked the perennial enemies of the wider Latin American right: the English, the Soviet Union, and the memory of the French Revolution. Graffiti even targeted 18th and 19th-century enemies such as the Masonic League. They threw bricks through the windows of politicians, businesspeople, and government officials. The office of the Senior British consul to Argentina, Mr. Puleston, was tar bombed and littered with fliers decrying the occupation of the Malvinas by the United Kingdom. Though Ezcurra himself isn’t known to have participated in these acts, he endorsed and defended them in newspaper interviews and public addresses, calling on more Argentine patriots to fight the nation’s long list of enemies.

Image of Tacuara graffiti in tar: “Frondizi (then President of Argentina), Jewish Lackey ¡Long Live Eichman! ¡Join up!

Ezcurra and the Tacuaristas didn’t just use slogans and stones to make their message heard. In 1960 a group of Tacuaristas invaded the Student Center of the Engineering College of La Plata, the capital of Buenos Aires province, shouting slogans, breaking windows, and firing guns at the rival student organization. Tacuaristas assaulted a peaceful demonstration by the Social Democratic Party in Miramar, ploughing a Ford into the crowd of protesters shouting “¡Viva Peron! Viva Franco! Viva Nacionalismo!” They shot at the students fleeing. One student was rammed against a tree. A dozen Tacuaristas once picked a fight with one hundred Jewish boyscouts at the beach — the resulting brawl had to be dispersed by the police. Dozens were injured.

Tacuaristas and Ezcurra had a purpose behind their violence. They were ideologues, giving media interviews, penning pamphlets and statements, reaching out to political allies and enemies, negotiating with the government to protect the members of the organization. Their violence served an ideological, nationalizing, invigorating purpose: it defended the nation from its enemies; it built new, battle hardened, Catholic men; it cemented the preeminence of Argentina’s Catholic and Spanish identity before the modernizing, Western alternative. Behind each of their targets, justifying each tactical move, were centuries of counter-revolutionary, conservative Catholic, and fascist thinking. Tacuara’s newsletter, which Ezcurra edited and wrote for, went so far as to issue reading lists full of difficult texts in multiple languages: from Jacques Maritain, to Thomas Aquinas (in the original Latin of course), to a treatise on the history of Protestantism in Spain from the sixteenth century onward. Tacuaristas weren’t uneducated men of the street but, like Ezcurra, disaffected members of high society, the falling stars of fading families. Their thuggishness was balanced with their embrace of conservative cultural theory and scholastic theology.

Eventually Ezcurra’s band of young men disintegrated into several splinter groups, much as Tacuara itself had originally separated from its parent organization. Some held true to the organization’s original radical right wing principles, but others became Trotskyists – one of their leaders is even said to have traveled to Vietnam to fight the US imperialists. These betrayals were hard on Ezcurra, who continued to lead the main branch of Tacuara until the late 1960’s, after which he returned to seminary in Paraná, capital of Entre Rios Province, and left the heart of Argentine civilization and power forever.

After he was ordained as a secular priest Ezcurra fulfilled various offices in the Church until finally landing in San Rafael, a small city in the dry and distant Mendoza province, where he was both a parish priest and attached to the local Seminario Mayor, educating future generations of clergy. There he lead his life relatively disconnected from the political world he had spent his youth influencing, performing the rites of his office, developing syllabi, and giving lectures at the seminary to seated, studious young men.

Ezcurra as priest

By contrast the lives of most Argentines had become vastly more dangerous and deadly in these years due in no small part to the destabilizing influence of Tacuara. After oscillating between civilian and military governments from the mid fifties to the mid seventies, in 1976 the Peronist government was overthrown by a military coup that ushered in a period known as “the Dirty War”, in which tens of thousands of Argentines suspected or accused of involvement in leftist politics were killed by the country’s far right military government and its paramilitary allies. Ezcurra was an open supporter of the military government, which he saw as a culmination of the the struggle against the Marxist, secular left. The Church had a complex relationship to the military government, with some priests ardently in favor of the national political cleansing and others in relatively silent opposition, like the man who would later become the Catholic Pope Francis I, who was at the time the provincial superior of the Jesuits in Argentina.

Ezcurra died peacefully in San Rafael in the early 1990’s, prompting a small flowering of eulogies and statements of grief and loss from the right-wing organizations that still look to his Tacuara for inspiration. Argentine nationalists have dedicated books, lecture series, YouTube tributes, short films, and even a webcomic to its legacy, and particularly to Ezcurra, loyal to his nationalist, right-wing, Catholic politics to the very end.

Webcomic, Ezcurra (glasses) speaking with other Tacuara founder José Baxter (smoking).

Ezcurra was a consummate reactionary who believed that only the better sort of people should rule, and that he and his fellow downtrodden elites should form the center of a political order that hearkened back to the Middle Ages, before the Protestant Reformation, before the rise of capitalists and businessmen, before the rule of the masses, when the bearers of natural and divine authority ruled as kings and clergy. And yet in another sense this story is as modern they come: a young man, down on his luck, who bands together with friends to try to change the world according to their vision for the future. This tension, between Ezcurra’s claim to believe only in tradition and the old, natural way of things, and his modern methods and tactics, runs through every other far right organization from Accion Francoise to the Nazi Party to the alt-right of today. This unstable marriage of the reactionary and the revolutionary is what makes far right and fascist politics so volatile – it captures the minds and bodies of young men, like Ezcurra, and demands that they build a new world in the image of the past with the weapons of the present.

Craig Johnson is a Ph.D. candidate in History at the University of California Berkeley, and holds a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from the University of Chicago (2011). His primary interest is the mid to late twentieth-century Southern Cone, principally Argentina and Chile, and at the confluence of religion and politics. Craig’s current research analyzes why and how the right-wing of Latin America engaged with a wider Catholic sphere, and how this should inform our understandings of right-wing politics and the contested place of religion in the modern world.

Leave a Reply