By Editor Derek O’Leary, in conversation with curator Diana Greenwold

It can be easy to imagine the early American republic as rushing headlong into the future during its first half-century—westward with the suppression of Indian society, seaborne to new markets with the products of southern plantations and western farms, upward in the growth of manufacturing hubs and cities, and in all cases away from the colonial past. Newspaperman and staple of any US history survey, John O’Sullivan celebrated in this “Great Nation of Futurity” “our disconnected position as regards any other nation; that we have, in reality, but little connection with the past history of any of them, and still less with all antiquity, its glories, or its crimes.”

This forward orientation was a common enough sentiment during these decades, yet one bound up in a much broader and Janus-faced preoccupation with the nation’s place in time. Biography burgeoned as a literary form (finely explored in Scott Casper’s Constructing American Lives, 1999); leading authors leveraged historical fiction to fashion a mythic colonial and revolutionary past; historical, antiquarian, and genealogical societies flourished as civic institutions. And in innumerable households, individuals and families marked their passage through time during years of seemingly unprecedented change.

The Portland Museum of Art’s exhibit “Model Citizens: Art and Identity from 1770-1830” (on view through January 28) provides fascinating insight into that latter world. It assembles a diverse array of household and commercial practices of marking pivotal stages of life in the early United States. Drawing on rich collections in Maine and New England art, it places in conversation a range of self-representation, organized around the life cycle: birth and childhood, marriage, adulthood, death and mourning. The exhibition recognizes its bounds within the white household, but in this space explores a far greater variety of lives and likenesses than we would typically see from this period.

Gilbert Stuart (United States, 1755-1828), Major General Henry Dearborn (1751-1829), 1812, oil on panel, Gift of Mary Gray Ray in memory of Mrs. Winthrop G. Ray, 1917.23

Diana Greenwold, PhD., who curated the exhibition, situated “stalwarts of the permanent collections”—such as the large and familiar oil portraits by Gilbert Stuart— alongside less elite likenesses produced in households and more accessible markets, such as samplers, shadow cutters, paintings by itinerant artists, and mourning embroidery (shown below). “For a long time,” she explains, “that type of folk portraiture was understood as being less sophisticated and telling of the moment,” a bias which the exhibition helps to revise. “By using different media,” she continues, “you open up the opportunity to show how different social classes can get at a similar goal. Not everyone can engage Gilbert Stuart, but cut paper can serve in a similar way for families to represent themselves, to both themselves and those around them.”

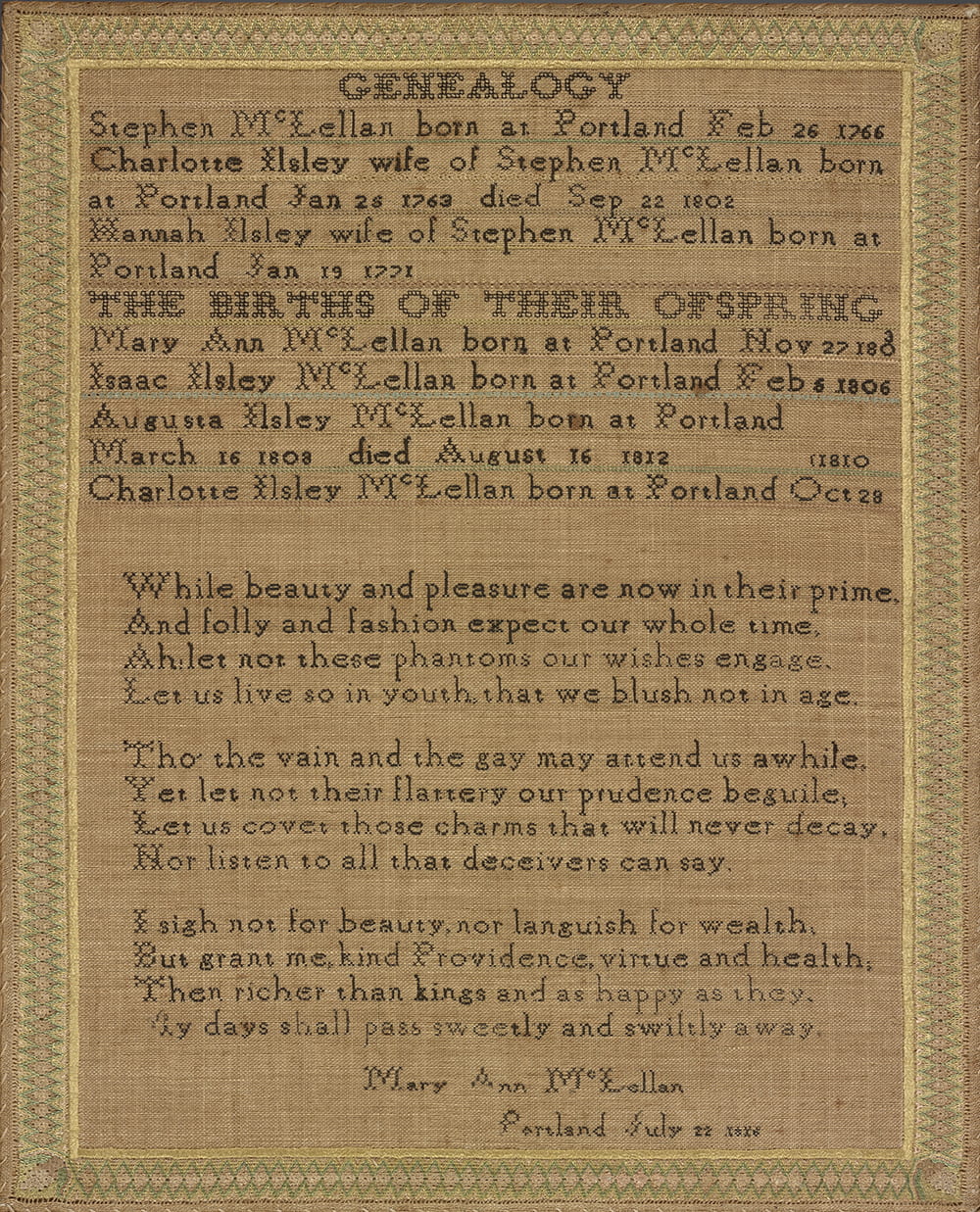

In depicting the shared life cycle of individuals of such disparate means, the exhibition thoughtfully examines the uses of these varied self-representations. Sewn samplers produced by middle- and upper-class girls in finishing schools served as stages to perform discipline, literacy, numeracy, and piety. But alongside sewn renditions of the alphabet, numbers, and biblical verses, girls might also inscribe their own name and age, or indeed, as in this peculiar rendition of a genealogy, a truncated, textual family tree.

Mary Ann McLellan (United States, 1803-1831), Stephen McLellan Genealogy Sampler, circa 1816, cotton on linen, museum purchase, 1981.1063

By the 1830s, genealogy would develop into a widespread household and academic practice, equipped with institutions, periodicals, and specialists who manipulated transatlantic connecting networks. (Francois Weil’s Family Trees (2013) is the recent major work on this phenomenon in the US.) Often, it sought to link the living in an unbroken chain backward, at least to the first Anglo-American settlements, and ideally eastward to their English origins. Yet, in a decade when genealogy had yet to emerge as a widespread practice, Mary Ann McLellan’s genealogical sampler (above) is striking: it places her father atop a small familial hierarchy, above his first and second wife and their four children. Paternity is overt; maternity only deducible by examining dates of birth and death. In this riff on a genealogical tree, more important than connecting the present to the past is inscribing an inter-generational duty: overseen by an elder generation, undertaken through a younger, promised to a future. “Let us live so in youth that we blush not in age”, the poem insists. The admonishment is surely a basic feature of gendered household management, but one cannot help but hear echoes of the broader national anxiety about the character and prospect of the country during these years, when the trope of the cyclical rise, corruption, and fall of republics was most potent.

Expanding on this analogy, Greenwold explains that “these domestically-scaled ways of representing self or family could become proxies for larger questions of national identity.” Especially in the works of childhood (produced both of and by children), “for a person in the early US, memorializing their children as the first generation of native-born citizens could be an act of establishment, visualized in a permanent and lasting way around virtues that were stressed for a new republic: industry, piety, family, etc. This notion of a domestically-scaled object had bearing not just on how folks were understanding their own families, but within a larger-scale participation in a budding national family.”

Though many of these were household products intended for a domestic space, perusing the exhibition, one can also imagine the markets for likenesses springing up in these decades before the more mechanized means of the daguerreotype and its successors. The shadow-cutters are the cheapest, visually starkest, and perhaps most arresting of works on display. Greenwold notes that these profiles cut into beige paper and pasted on black background (and sometimes vice versa) were produced at once by itinerant artists, as a popular parlor game, or in such venues as Charles Willson Peale’s Museum by means of a physiognotrace. The exhibition explains the special appeal of the profile—which features the chin, nose, and forehead—in the field of physiognomy, which sought to discern character in the subject’s facial features. In these shadow cutters of the women of the Stone family, distinctive hair styles have been inked around the silhouettes. Historian Sarah Gold McBride, whose work examines the significance and uses of hair in the nineteenth century, argues that in addition to physiognomy, hair style, texture, style, and color conveyed clues to one’s character in this period. (See her dissertation “Whiskerology: Hair and the legible body in nineteenth-century America” (2017) for more on this.)

Unidentified artist (United States, 19th century), Cut paper silhouettes of the Stone Family, 1917.11-.18

These were often products of fleeting popular or commercial transactions. However, in addition to revelations of character, as small and easily transferable objects these likenesses-and more specifically portrait miniatures painted in watercolor on ivory-could be more intimate than the finely painted portraits of Stuart or John Singleton Copley. Greenwold elaborates, that “they are meant to be very portable and physically held, near the heart or the body. That sort of physical embodiment of a loved one does something categorically different than something that hangs in a parlor, such as an oil on canvas portrait, that would be both for family and the larger group of visitors who would be in your home.”

If girls mainly executed the works of childhood in this collection, and mostly men those of adulthood, women undertook the tasks of mourning represented here. Though there are cases of men making some of the outlines of such mourning embroidery, Greenwold discusses that “in this nineteenth-century moment, women were becoming the vessels through which a family performs its mourning—the public face through which a family expresses grief, for instance.” Bedecked in Greco-Roman iconography, balanced around a central urn inscribed with the dates of the departed, these “classically-draped figures intertwine with a lexicon of Christianity, forming a hybrid language of pagan and Christian.” It is a common aesthetic aspired to by the middle to affluent classes in this period, but one which suggests again how the marking and performance of the life cycle in the early US was enmeshed with the larger concerns of the place of the American citizen and republic in history.

Susan Merrill (United States, 1791-1868), Memorial to Mrs. Lydia Emery, 1811, watercolor and needlework on silk, Gift of Helen Harrington Boyd in memory of Susan Merrill Adams Boyd, 1968.4

January 17, 2018 at 1:04 pm

Thank you for the review of this local exhibit!

January 17, 2018 at 8:58 pm

Thanks, Michelle! It’s a wonderful museum and city.