By guest contributor Trish Ross

For the full companion article, see this Winter’s edition of the Journal of the History of Ideas.

“Human nature is the only science of man; and yet has been hitherto the most neglected.” Thus David Hume simultaneously lamented the past and hailed a bright future for the sciences humaines in the eighteenth century. Historians have, by and large, assumed the narrative eighteenth-century thinkers like Hume devised, tracing the development of the social sciences, and in particular, anthropology, to the Enlightenment and colonialism. (Popular pastiches like Steven Pinker’s purvey a whiggish knockoff of this narrative with little concern for precision and care.) But had the study of human nature really been neglected? If the study human nature was not ignored before the eighteenth century, and if it is the foundation of the human sciences, how might that change our historical narrative about the goals and the development of disciplines familiar to us?

Contrary to Hume’s claim, dozens of learned early modern humanists, physicians, theologians, and philosophers of all religious confessions produced a series of texts that show them laboring to study and understand what Hume charged past thinkers with disregarding: human nature. They often spoke explicitly of their topic as “natura humana.” Operating across what we retrospectively classify as distinct scientific, social scientific, and humanistic disciplines, they integrated empirical research and experimentation with intricate natural philosophy and complicated theologies in a wide-ranging attempt to understand human bodies and souls. Focusing on one of the names they gave their study is as revealing as the undertaking itself. They termed it “anthropologia.”

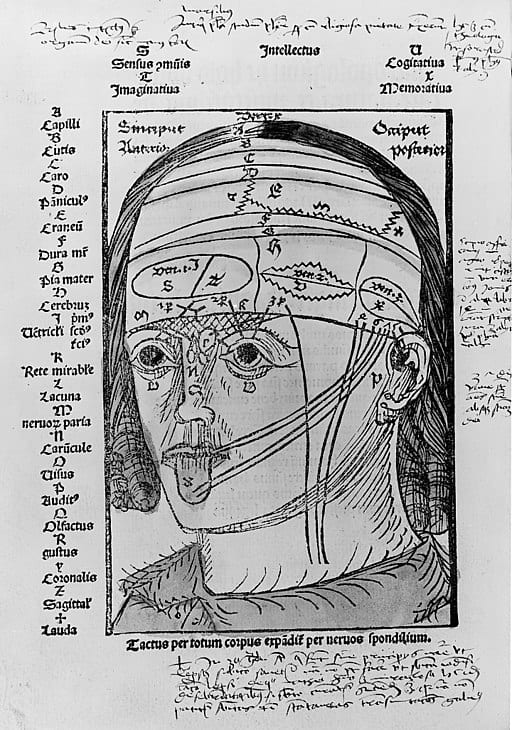

Magnus Hundt, Anthropologium (1501).

Long before the development of the eighteenth-century human sciences and before anthropology became a modern academic discipline, over thirty books appeared in Europe between 1500-1700 that include the word anthropologia in their titles, starting with the earliest so far identified: Magnus Hundt’s Anthropology, on the Dignity, Nature and Powers of a Human Being [and] the Elements, Parts, and Members of the Human Body (1501). Studying these texts and what their early modern authors meant by the term anthropologia requires suspending impulses anachronistically to read our own disciplinary divisions into the past. Yet doing so offers insight into the ways in which sixteenth- and seventeenth-century religious and philosophical debates intersected with scientific developments and, as time went on, with reports about new lands and peoples from beyond Europe to encourage the development of what would become the modern human sciences.

At first glance, the content of these works bears little resemblance to anthropology as we think of it. Sixteenth-century texts with the term covered everything from detailed anatomies to discussions of the soul inspired by the long tradition of commenting on Aristotle’s De anima to a humanist dialogue about gender to descriptions of the history and customs of peoples. Around the beginning of the seventeenth century, the term started to be used primarily to describe studies of the body (anatomy and physiognomy) and the soul (philosophical and theological anthropology). The German physician Johannes Magirus’s Anthropologia (1603), a fulsome commentary on the more famous Philip Melanchthon’s works on natural philosophy and the soul, was a turning point. After Magirus’s book appeared, anthropologia texts by philosophers, physicians, and theologians came off the presses in greater numbers. Thereafter anthropologia, as a multi-faceted study addressing the physical, religious, and moral aspects of human nature, provided grounds from which eighteenth-century (and later) human sciences developed.

James Drake, Anthropologia Nova (1707).

Anthropologia and its vernacular variants continued to be used in this way to denote the study of anatomy and the soul up to and even through the eighteenth century, such as in James Drake’s Anthropologia nova (1707). Out of this usage grew eighteenth-century French “anthropological medicine,” described by Stephen Gaukroger and Elizabeth Williams, with its focus on the body-soul nexus and its concern with moral questions and human nature.

Moreover, anthropologia developed out of and fortified a tendency to understand human bodies as disclosing moral or theological truths, as well as out of post-Reformation debates about the extent of sin’s effects on human souls and bodies. Some took this to what seem to us perhaps amusing extremes, such as the Lutheran theologian Christoph Irenaeus, who argued that sin is the reason defecation smells. In its study of bodies and souls with a view to understanding what they revealed about human nature, anthropologia was related to the flourishing early modern practice of physiognomy, widely tied by scholars to early theories of race and and social order. This search for truths about human nature, stripped of their inherited natural philosophical and theological roots, in turn encouraged the development of anthropology.

Kant, Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht (1799)

Early modern “anthropologists” used this interest in the truths discernible from body and soul to ground arguments about natural law, and theories about the proper order of the world and differences between types of people on the study of bodies and souls. In this way, their longstanding interest in and study of human nature and souls eventually was combined with debates about the capacities of peoples encountered in the Americas and Asia, speculation about whether and how these people and Europeans descended from common ancestors, and widely popular travel literature to inform influential arguments about human nature and diversity as well as the first attempts to theorize race. This is the heart of the connection between anthropologia, natural law, and ethnography that developed among German intellectuals, leading up to Kant’s important lectures on anthropology. By 1808, the Englishman Thomas Jarrold utilized the term for a book on racial differentiation entitled, Anthropologia: or Dissertations on the Form and Colour of Man.

Notwithstanding Hume’s proud boast about founding the study of human nature, eighteenth-century studies of it grew out of a tradition of thought about it, summed up in words sometimes strikingly familiar to us today. Intra-disciplinary divides between histories of the Enlightenment and nineteenth-century science on the one hand, and early modern natural philosophy, medicine, and religion on the other have hitherto obscured the way in which earlier studies bearing the name “anthropologia” evolved into later ones. Taking this early modern study seriously in (literally) its own terms highlights how questions raised by physicians, natural philosophers, and theologians in recondite and seemingly repetitive Latin treatises and disputations gave rise to a discipline that is more familiar to us in range and content. Though not coterminous with the later sciences humaines, recovering this earlier effort by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European scholars to understand human nature by drawing on religious and scientific thought can deepen our understanding of what shaped the development of the human sciences, including what their eighteenth-century successors rejected from the past and what they quietly retained. Anthropologia reveals how disciplines we use to study ourselves developed from an all-but-forgotten natural philosophical and religious discourse that was slowly secularized in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Trish Ross is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Queensland, Australia.

Leave a Reply