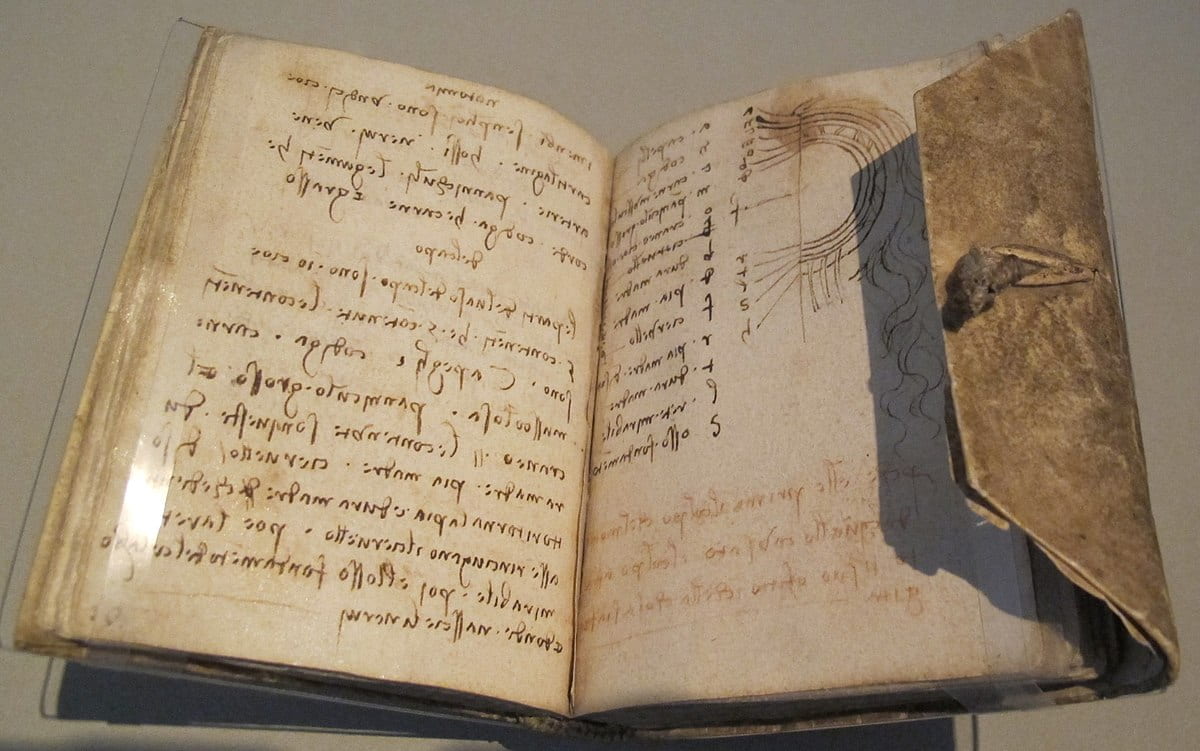

Leonardo Da Vinci, taccuino forster III, 1490 ca.

Here is the third installment of some of the books that the Blog’s editors have lined up for summer. From art history to critical theory, from fiction to poetry, we’ve got you covered if you’re looking for something to pick up during the academic off season.

A.J.

Aside from my research-related and departmental work, my summer list is a bit wide-ranging, owing to the fact that it’s also basically a stack of books that have been set aside for when I had the time. Either way, I’m very excited about all of them. I’d love to hear your thoughts if and when you get to one of the books below!

The Drama of Social Life, Jeffrey Alexander: I studied under Alexander while I was at Yale and his theoretical approach has had a profound impact on my thinking, so I’ve been excited to get around to reading his latest for a while now. In it, he combines elements from dramaturgy and social theory to explore the central role “cultural pragmatics” plays in the political possibilities of social life. Gary Fine, a professor at Northwestern, said the book is one that “demand(s) to be read and discussed”.

Finding Mecca in America, Mucahit Bilici: What does Islam look like in the United States? Bilici draws from Simmel and Heidegger and develops a novel approach examining the gradual process by which American Muslims have navigated the journey from social periphery to citizenship. I’ve been meaning to get to this book for too long and have heard nothing but wonderful things from a wide variety of people.

Islam Translated, Ronit Ricci: Another book that’s haunted my shelf for longer than I’d like, Islam Translated explores the translation of the Book of One Thousand Questions into various Southeast Asian languages as a means of investigating the connections between Muslims in different contexts. It is, by all accounts, beautifully written, novel, and insightful. And given my area of study, probably critical.

The Ticket that Exploded, William S. Burroughs: I’ve never actually ready Burroughs’ prose before, but this book in particular has quite the reputation. The first of three novels that he wrote using the cut-up technique, it’s evidently mind-bending, dark, and enthralling. Personally, I’ve found that my brain works best when it sits with genius in fields far from my own. And that is certainly an apt description of Burroughs.

Sarah:

My recommendations come from the vantage point of the southern hemisphere, where we’re heading into the winter break and thus academic conference season. Consequently my reading time will be snatched in broken fragments from ‘plane flights and train journeys. It is fitting then that my list begins with Zone, a 2015 collection of some of Guillaume Apollinaire’s poetry and a book that can be read all at once or dipped into for a page here or there. Each poem is printed first in French and followed by an English version translated by Ron Padgett. Padgett is himself an accomplished poet and his talents as a wordsmith shine through in these translations. The result is a beautiful collection that showcases the richness and potentiality of both languages.

Earlier in the year I picked up a copy of Nobel Prize Winner Svetlana Alexievich’s The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II. As the title suggests, the book brings together hundreds of interviews conducted by Alexievich with Russian women about their experiences during the War. The result is a compelling and immersive history of the Second World War and a testament to how that war shaped the lives of the Russian women who survived it. It certainly gave me a great deal to contemplate as I embark upon a new research project that entails working with oral histories. Alexievich is definitely a master of the genre. She is probably best known for her sensitive rendering of the human cost of the Chernobyl catastrophe, Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, through the eyewitness accounts of hundreds of survivors. If you enjoyed that, I guarantee The Unwomanly Face of War will also appeal. If you haven’t read Voices, then you should add that to your summer reading list too!

And finally, I cannot wait to read Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”. The book is the story of Cudjo Lewis, born Oluale Kossola, one of the last slaves brought to America. Kossola was brought across the Atlantic to Alabama from Dahomey (present day Benin) on the Clotilda in 1860, half a century after the slave trade was officially abolished. Hurston, studying to be an anthropologist, conducted a series of interviews with him in the late 1920s. By then, Kossola was the last living survivor of the middle passage crossing. The conversations between Hurston and Kossola are at the heart of Barracoon which Hurston wrote in the early 1930s. She took great pains to relate the cadence and form of Kossola’s storytelling in the book, capturing the African Creole of his speech patterns. This choice is, in part, why Barracoon has just been published for the first time. Publishers declined to take on her manuscript unless she ‘anglicized’ Kossola’s speech. Hurston defiantly refused. As a result, the manuscript languished in the archives for decades, read only by select historians who came across it in a private collection at Howard University.

Leave a Reply