By Contributing Writer Shane McCorristine. See Shane’s book-length study around this topic, The Spectral Arctic (2018).

For centuries British explorers and their audiences imagined the Arctic as a place of magic and mystery, an otherworldly environment where ships and men could vanish beneath the enchanting rays of the Aurora Borealis. This Arctic imagination went beyond aesthetics: notions of a spectral Arctic inspired people to develop new relations to the region, through practices such as consulting psychics, reporting strange dreams, and engaging with Inuit shamans in the field.

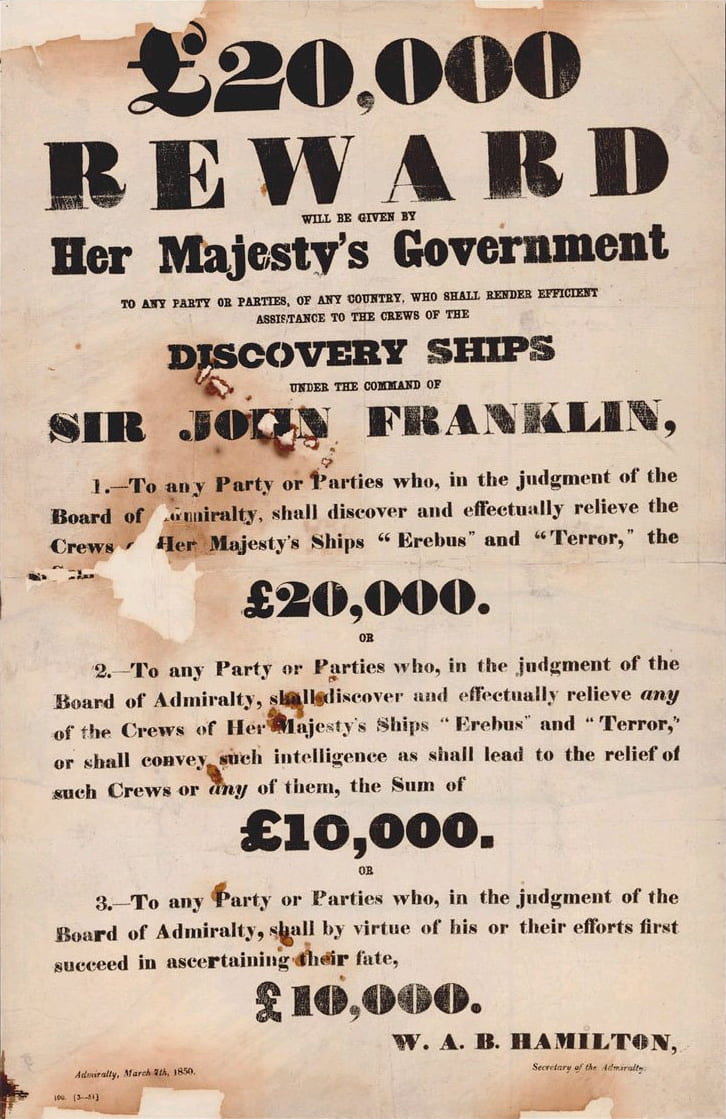

Poster offering a reward for help in finding the lost expedition

At the center of this story is the disappearance of Sir John Franklin’s Northwest Passage expedition. In 1818 the British Admiralty rebooted the early modern quest to explore and map what is now the Canadian Arctic, in order to discover a maritime shortcut to Asia. After several failed attempts, in 1845 Franklin was headhunted to lead 128 officers and crew into the Arctic ice onboard the restructured bomb vessels HMS Erebus and Terror. In their second winter, the ships became locked in the ice near King William Island and after dozens of deaths (including that of Franklin) in April 1848 the survivors abandoned the ships and launched the first of several doomed attempts to reach the Canadian mainland.

The disappearance of the expedition, a loss perhaps comparable to the recent MH370 plane disaster, sent shock waves through Victorian Britain, inspiring an outpouring of gothic speculations on the mystery and causing the Admiralty to downsize its subsequent polar expeditions. Early search and rescue attempts by the Admiralty and other polar experts came to nothing, and this created a powerful information vacuum.

Ordinary people in Britain quickly seized the opportunity to speculate wildly, and in 1854 revelations about cannibalism among the starving survivors led to further dark imaginings. Through media such as panorama shows, ghost stories, letters to newspapers, seances, and dreams, people felt they could intervene in the mystery, creating new ways to connect with the Arctic. The Frozen Deep, a play written in 1856 by Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens, emerged from this confluence of Arctic exploration, popular culture, and supernatural experience. This was a democratisation of the culture of Arctic exploration and a challenge to the long-held authority of the Admiralty over the region.

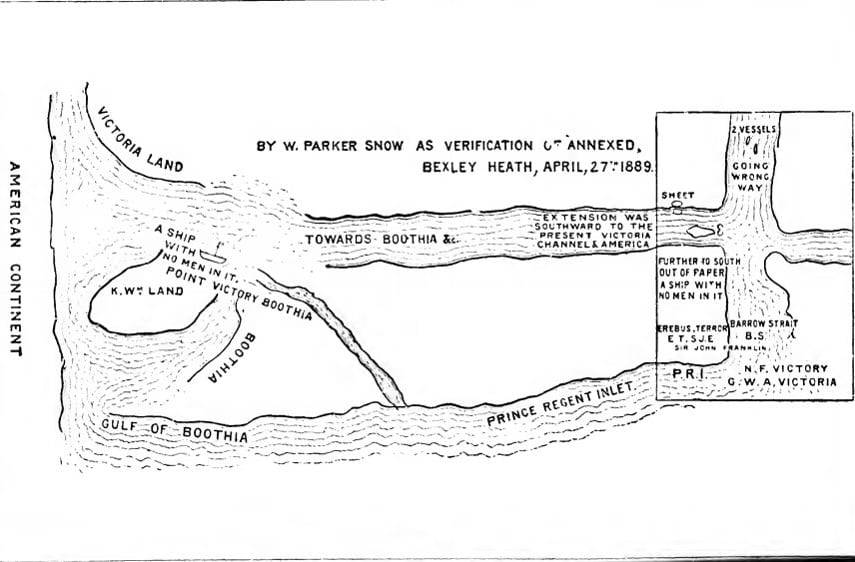

Chart of a vision experienced by the explorer and mystic William Parker Snow (Skewes, 1890).

A good example of this can be seen in an anonymous letter sent by a “Humble and true dreamer” to Jane Franklin, wife of the explorer, in 1850. In it the correspondent detailed a “remarkable dream” they had of two “Air Bloon’s” in the Arctic, one which was destroyed and another which “stands well” among the inhabitants of the region – a providential sign, the correspondent believed, that Franklin would return to Britain soon on his ship (Polar Archives, Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, SPRI, MS 248/335; D). This link between dreaming, ballooning, and the Arctic is worth exploring further because it demonstrates how a spectral Arctic imagination was expanding the relationship between ordinary people and a region that was previously only accessible to Admiralty explorers.

By the time of the Franklin expedition aeronautics had caught the public imagination, appealing to scientists, dare-devils, monarchs, and the massive crowds that paid to attend ballooning spectacles and experiments. The balloon was attractive by virtue of its novelty, danger, and potential, but it also highlighted the links between air, emotions, and mobility. As things which affected, and were profoundly affected by, atmospheres, balloons confused the boundaries between materiality and immateriality, between technology and dreams (McCormack, 2010).

In the context of Arctic exploration, ballooning has mostly been associated with the Swedish expedition led by Salomon August Andrée in 1897. In July of that year Andrée and his two companions left Danskøya, northwest of Spitsbergen, in the hydrogen balloon Svea on a voyage towards the North Pole. Andrée’s expedition vanished without a trace until 1930 when passing sealers discovered the remains of their bodies and final camp on the island of Kvitøya in the Svalbard archipelago.

“Salomon Andrée’s balloon takes off from Danes Island”

Andrée’s balloon expedition became a gathering point for dreams and fantasies as rumors circulated, untethered, around the disappeared object. Indeed, barely two weeks after Andrée’s departure, reports reached Britain of a “Parisian prophetess” who had followed the balloon expedition “in spirit” to the North Pole. There she discovered that it was not made up of “ice and perpetual snow, but of luxuriant grass and umbrageous trees” (The Aberdeen Journal, July 22, 1897).

However, Andrée was not the first to propose using balloons to navigate the Arctic regions that naval and land-based expeditions found so difficult to traverse, nor was his expedition original in taking to the air. In fact it was the disappearance of the Franklin expedition decades earlier that activated aerial fantasies of exploration.

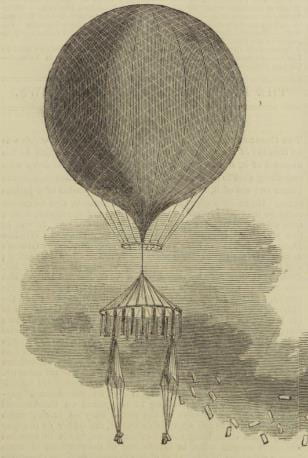

“Mr. Green’s Signal Balloon, Dispatches, and Parachute for the Arctic Expedition”, Illustrated London News, May 11, 1850.

After finding no sign of Franklin through land and naval expeditions, in the early 1850s officials in the Admiralty began experimenting with aerial means of search and rescue. Rockets and kites launched from ships in the Arctic were not very successful, but the Admiralty placed more hope in a newly designed messenger balloon – an apparatus made of oiled silk and filled with hydrogen. The balloon’s basket contained a slow-match that would, after a launch from a ship, cause a gradual scattering of hundreds of colored pieces of paper and silk on the ice for hundreds of miles, giving lost explorers details of rescue ships in the vicinity. In practice the furthest distance these papers were found from a ship was only 50 miles.

This was a period of “ballooning mania” in Britain and the mystery of the Franklin expedition started to attract aeronauts who vied for attention from the general public and the Admiralty. In October 1849 Lieutenant G.B. Gale wrote to Jane Franklin volunteering to voyage by balloon in search for her husband’s expedition. Gale’s proposal was to ascend from an expedition ship in his balloon where, if he gained a height of two miles, a “panorama of at least 1,200 miles would be placed within observation”. Gale’s idea received a mixed reception in the press. The Era balanced its ribbing of this “‘Columbus of the skies’” with an admission that it could be of great benefit (The Era, October 28, 1849). A rather more scathing riposte came from Punch which, predictably, could not resist lampooning the aeronaut’s unfortunately appropriate surname:

Imagination forms icicles on the tips of our nose as we figure to ourselves the daring GALE ‘blow high, blow low’, with the thermometer 15 degrees below zero, his gas contracted, his balloon congested into a flying iceberg, or like the head of an airy giant with his night-cap on, while the poor frozen out aeronaut surveys his brandy-bottle solidified into a mass of ice à la Cognac, and his cold fowls too cold for his knife to penetrate them. The mere picture throws us into a chilly pickle; and we trust GALE, for his own sake, will not be able to raise the wind for so absurd a purpose (Punch, 1849)

Yet as affectual forces traveled back and forth from the Arctic, balloons actually did allow people to think with the Franklin expedition, in terms of their ability to “balloon back” with news. Around this time it was reported that a woman in a mesmeric trance claimed to have “ascended in a balloon, and proceeded to the North Pole in search of Sir John Franklin”. The woman found Franklin alive and well “and her description of his appearance and that of his companions was given with an inimitable expression of pity” (Carpenter, Quarterly Review, 1853).

As with clairvoyantes, balloons drew the Arctic and Britain into new spatial relationships because they enacted an aerial subjectivity that was untethered by the Franklin disappearance. As a metaphor for a geography of the spectral Arctic, balloons unsettled the “where” of the Arctic, activating techniques and technologies of what McCormack calls “remote sensing”, a geographical practice that is also spectral in that it “is always remote yet always potentially sensed as a felt variation in a field of affective materials” (2010).

Dreams of polar flight did not decline with the passage of time and shift to a different geographic quest. During the preparations for his final North Pole expedition (1908-9), Robert Peary received a flood of “‘crank’” letters from members of the public offering unsolicited advice and counsel, and “flying machines occupied a high place on the list”. One inventor even gamely proposed that Peary play the part of a “‘human cannon ball’”: “He was so intent on getting me shot to the Pole”, Peary wrote, “that he seemed to be utterly careless of what happened to me in the process of landing there or how I should get back” (Peary, 1910).

Yet “crank” letters like this remind us that Arctic exploration could be performed in many ways. Now that the Northwest Passage had become a labyrinth crowded with cumbersome and bumbling search and rescue expeditions, movement through the Arctic was fantasized to be dreamlike and flighty.

From the throbbing silences of the Arctic diverse audiences sensed a multiplicity of voices which meant that Franklin was now circulating uncontrollably through strange dreams, rumors, mesmeric visions, and balloons. Through clairvoyance and mesmeric trances, women were suddenly a major part of these cultural productions of remote sensing, taking on the “Icarus” perspective that characterized so much of masculinist fantasies of actual polar exploration. As someone who was affected and affecting, Franklin went from being a contained explorer outside the world to a body that gathered together the heterogeneous thoughts, dreams, and emotions of unsolicited audiences and new international explorers. In all this, the otherworldly was worldly; dreams had a social history and were not sudden eruptions of the irrational.

Shane McCorristine is a lecturer in Modern British History at Newcastle University where he specializes in the cultural histories of exploration, death, and the supernatural. He graduated from University College Dublin in 2008 and then gained postdoctoral fellowships in Maynooth University, University of Cambridge, and University of Leicester. His website is http://www.shanemccorristine.net and his new book (available in open access) is entitled The Spectral Arctic: A History of Ghosts and Dreams in Polar Exploration (UCL Press, 2018).

Leave a Reply