By Andrew Klump

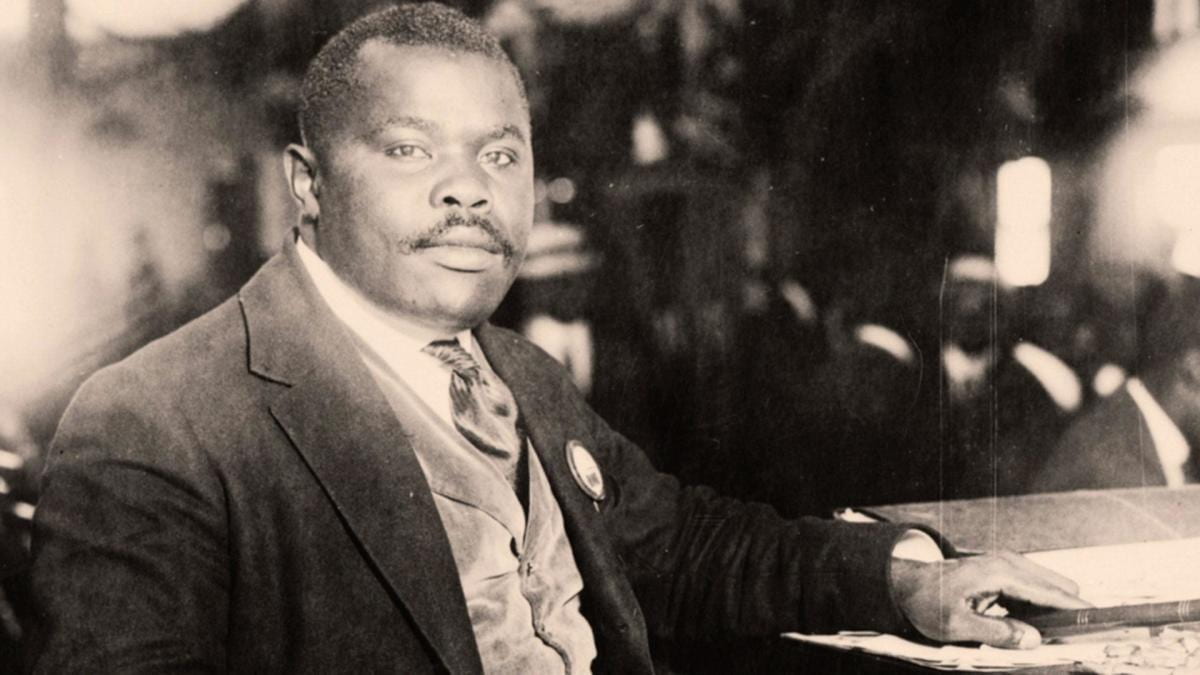

Evangelists, statesmen, and academics once dominated many histories of religious ideas, but in Tisa Wenger’s recent Religious Freedom: The Contested History of an American Ideal (UNC Press, 2017), they are eclipsed. Figures like the Moros Muslim sultan Kiram II, black nationalist Marcus Garvey, archbishop of the Philippine Independent Church Gregorio Aglipay, the founder of the Moorish Science Temple Nobel Drew Ali, and the Native American Shaker prophet John Slocum take center-stage. Spanning the decades from the Spanish-Cuban-Filipino-American War until WWII, this study weaves together diverse communities ranging from Filipino Muslims to Jewish immigrants, the Nation of Islam to practitioners of Native American traditions such as Peyote and the Ghost Dance. Although globetrotting in scope and diverse in its subjects, Religious Freedom’s persistent attention to how interpretations of religious freedom relied on the formative relationship between race, religion, and empire effectively ties the study together.

Much like Wenger’s first book, We Have a Religion (UNC Press, 2009), which investigated the formation and use of the category of religion among Pueblo Indians, Religious Freedom focuses on a fundamental concept, in this case religious freedom, and explores its formation and re-formation by those outside of the halls of power in the United States. In doing so, it offers a fresh perspective on central questions about religious liberty, nation-states, and global empire. It also provides a window into engaging trends in how historians of religion and ideas approach their work and frame their questions.

Forged at the nexus of race, religion, and empire, religious freedom, Wenger argues, was not always universally beneficent. Consequently, when various communities invoked the ideal, winners and losers emerged. She convincingly demonstrates that white American Protestants, in particular, deployed the ideal of religious freedom to assert their supremacy and highlight the deficiencies of others.

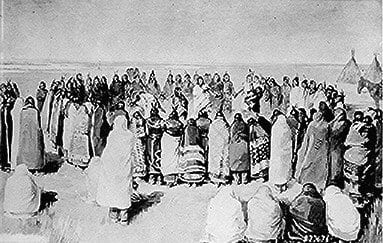

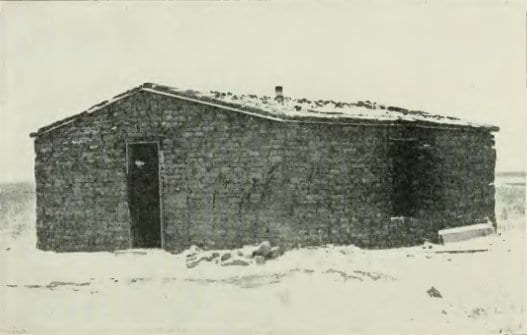

In order to further these broader arguments, Religious Freedom explores contexts ranging from Muslim settlements in the Philippines to Native American reservations in the Dakotas. For example, perceived racial inferiority meant that Christianity served as a key civilizing force in the Philippines after the U.S. conquest of the islands. Nevertheless, this otherness also kept Filipino Catholic priests under the thumb of a Western bishop. Racial otherness also cast suspicion on Native American religious practices. Missionaries and government officials nursed a longstanding skepticism about Native American religious practices including Peyote, the Ghost Dance, and the Native American Shaker tradition, even when these traditions exhibited some of the trappings of Christianity.

Wenger also deftly reveals how some groups leveraged their religious identities to minimize perceived racial otherness and inferiority. American Jews in both the Reform and Orthodox communities tended to lean into their religious identities and minimize their racial and ethnic distinctiveness. By framing their differences as religious rather than racial or ethnic, Jews, as well as Catholics, wielded the language of religious freedom to secure a spot standing shoulder to shoulder with white American Protestants.

Overall, Wenger’s book is remarkably successful. It explores an understudied chapter in the definition and deployment of religious freedom ideology and expands its study to a broad and engaging collection of individuals and communities. Nevertheless, Religious Freedom is, somewhat disappointingly, largely a story of men. Only a handful of women appear throughout the entire text. This is particularly unfortunate because of the tradition of exploring the relationship between gender, race, and civilization, yet this vein of inquiry remains underexplored. Some of this is due to the sources Wenger uses and the prominence of men in the military, government agencies, and religious leadership at the time. Nevertheless, a woman like Alice Fletcher—discussed as an example of the of the interplay between race, gender, and civilization in Louise Michele Newman’s White Women’s Rights (Oxford University Press, 1999)—was active in the Women’s National Indian Association, and women like Fletcher might provide valuable insight about this topic. In this way, Wenger’s work provides an excellent platform for future explorations of the role of women in discourses about religious freedom, race, and empire.

Taken on its own, Wenger’s work is excellent scholarship and a valuable contribution to the field, yet it also provides an enlightening lens through which to appreciate some of the trends in the history of ideas, particularly as it relates to those of us who study religious history in the United States. At the most fundamental level, Religious Freedom deftly balances many of the lessons learned from social and cultural history—notably its attention to minority communities and global contexts— while remaining decidedly a history of ideas. Wenger’s study looks beyond politicians, preachers, and government officials, and that significantly reorients her history. Men like William Howard Taft, the governor-general of the Philippines and future president, or W.E.B. Du Bois appear only briefly. The focus remains on the leaders and members of each of the religious communities she explores.

In doing so, Wenger offers her take on whose ideas contribute to intellectual history. Is the history of ideas primarily about those who wrote books, set policy, and preached sermons, or is it broader than that? Wenger unequivocally answers with the latter definition. To be sure, she does not discount men like Theodore Roosevelt or William James, yet her attention to Jewish immigrants and colonized Filipinos (both Catholic and Muslim), as well as Native Americans and African-American religious movements, tells a more complicated and robust story. Though government agents and prominent religious thinkers engaged with the ideal of religious freedom, this approach to the history of ideas does not privilege their voices. Wenger illumines an expansion in the subjects studied by those of us who work in the history of ideas by intentionally integrating previously overlooked voices.

The centrality of race and racial hierarchies to the history of religion, both in the United States and in a global context, is another significant historiographical theme that Wenger continues to develop. She joins a bevy of excellent scholarship that has emerged at this intersection of religion and race, such as J. Spencer Fluhman’s “A Peculiar People:” Anti-Mormonism and the Making of Religion in Nineteenth-Century America, Rebecca Goetz’s The Baptism of Early Virginia: How Christianity Created Race, and Max Perry Mueller’s Race and the Making of the Mormon People. The history of religious ideas in the United States cannot be divorced from conversations about race. Wenger joins a growing chorus in making that point. As she argues in her book, race must be considered as a constitutive part of the development of religious ideals, not simply another factor to consider.

The consistent theme of the American empire also looms over this study. It forms a key part of Wenger’s argument and gestures toward another development in the history of religious ideas. Global contexts increasingly appear in the history of U.S. religion and religious ideas, even when focused on an “American ideal,” as Wenger’s title suggests. This study does just that, but it is not alone. For example, Cara Burnidge’s A Peaceful Conquest: Woodrow Wilson, Religion, and the New World Order or David Hollinger’s recent Protestants Abroad: How Missionaries Tried to Change the World but Changed America are just two examples of works that touch on similar themes of empire, American religion, and global contexts. Religious Freedom not only emphasizes this growing theme but also furthers the argument that a global lens is necessary for understanding the history of religious ideas in the United States.

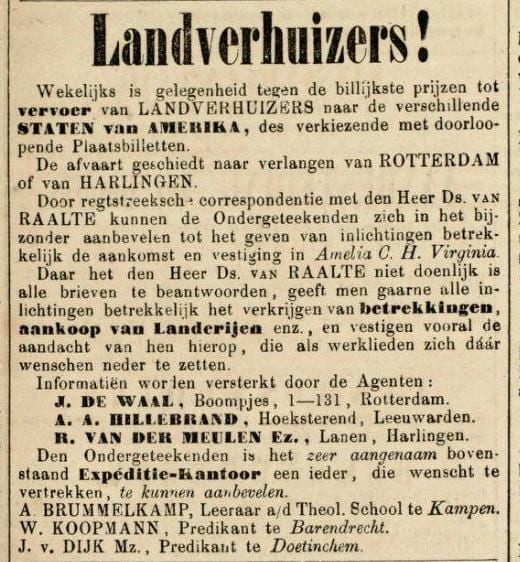

The themes that Wenger highlights—diverse voices, race, and global contexts—also resonate in the prairies and farmsteads that populate my own work as a historian of religion in rural America during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. In particular, her contention that global forces shaped far-flung communities rings true of the rural communities that I study. Increasingly in my own work, I find the tiny hamlets strewn across the Midwestern plains engaged with global forces and positioned themselves in order to benefit from them. Markets and commodities form the best-known examples of rural America’s place in a global network, yet I find that ideas flowed just as freely as crops, livestock, and other essential goods. For example, when rural communities rejected or embraced religious movements like the Social Gospel or Pentecostalism, they often drew upon their own self-conceptions of how their community fit into regional, national, and international contexts. Relatedly, these same networks allowed relatively homogenous rural communities to take part in discourses about race, revealing yet another central theme of this work that appears in my own. The international network that shaped, exchanged, and refined ideals of religious freedom did not pass over rural America.

Religious Freedom is engaging, rich, and valuable scholarship on its own, but when placed within the field, it is also an instructive guide to themes that are shaping the scholarship about the history of religious ideas in the United States. It answers the question of whose ideas can become the subject of intellectual history by casting a wider net, in a way that resonates with my own efforts to introduce rural voices into the scholarly conversation. Ultimately, this excellent piece engages readers, integrates compelling new voices, and inspires others to do the same.

Andrew Klumpp is a Ph.D. candidate in American Religious History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, TX. He holds degrees from Northwestern College in Orange City, Iowa and Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. His research explores how rural Midwestern communities engaged in nineteenth-century debates about religious liberty, racial strife and social reform.

Featured Image: Alice Fletcher speaking to Native Americans.

September 24, 2018 at 9:41 am

Reblogged this on Project ENGAGE.