By guest contributor Jake Newcomb

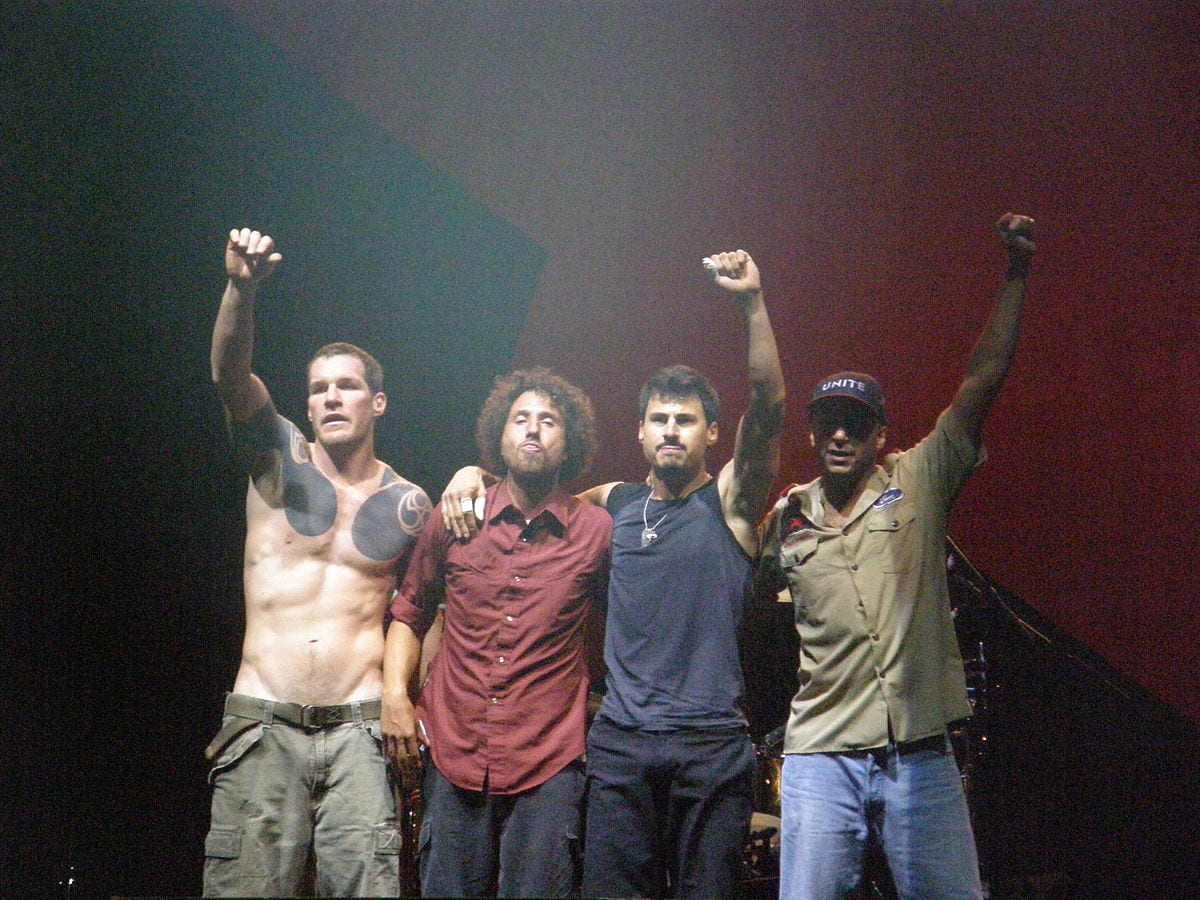

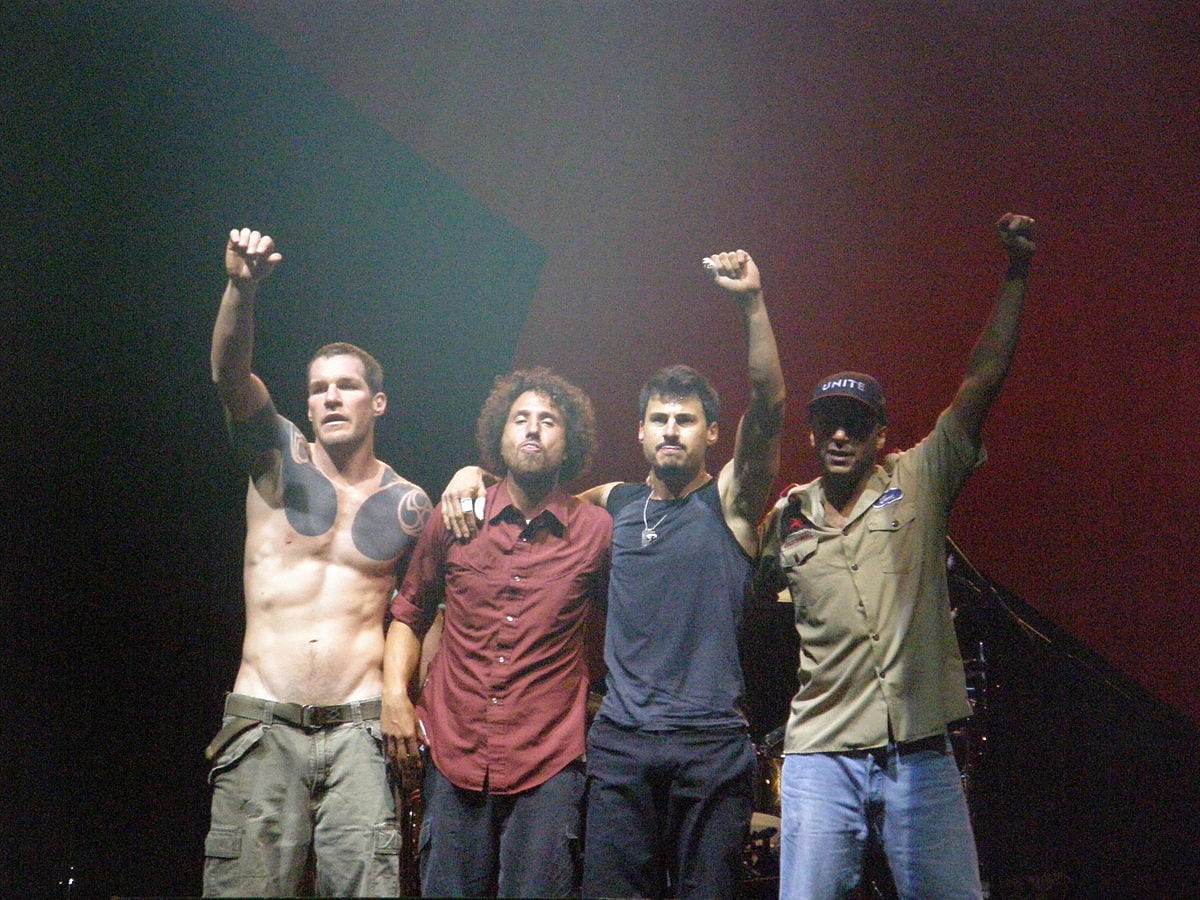

Rage Against the Machine End of set, before leaving stage

Vegoose Music Festival, 28 October 2007. https://www.flickr.com/photos/penner/1977294428/

With the publication of Rhythm and Noise: An Aesthetics of Rock, philosopher Theodore Gracyk made the first breach into a modern ontology of rock music in 1996. Gracyk’s ontology postulated the idea that rock music is separated from other genres of music by identifying sound recording as the most important facet of the genre of rock music – which contrasts the centrality of live performance in classical music. By downplaying the role of live performances, songwriting, and songs themselves in the ontology of rock, Gracyk’s left his assertion open to critique. Some of the critiques that followed Gracyk’s ontology, like Andrew Kania’sin 2006, keep the ontology of rock music “recording-centered,” but try to refine the exact contours of what “recording” is. Kania also acknowledged that rock music is a recording centered phenomenon, and argued that the primary goal of rock musicians is to “construct [recorded] tracks,” as opposed to writing songs. Kania used this assertion to then make the claim that recording tracks precedes the existence of a song, and that it isn’t until after a track is recorded, that a “song” can exist. In 2015, Franklin Bruno entered the debate, arguing not only that songwriting and the existence of songs can precede the recording of a track, but also that the quality of songwriting and songs are as important to the fans of rock music as the skill of recording tracks. Bruno emphasized the viewpoint that songs and recordings are not mutually exclusive, but mutually dependent.

This chain of argumentation leaves out the cultural and social dimensions of rock music, which could be of particular interest to historians. Rock musicians have openly defied the status quo and socio-political norms of their times, and became symbols of resistance to the social structures that surrounded their art. Defining moments in the development of rock, and how that development was perceived by the public, are entangled with the contemporary political and economic situations that surrounded those moments. The examples below demonstrate how rock musicians have symbolized social and political conflict.

Take for example, the identity of Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain in the 1990s. In, The Man Whom the World Sold, Mark Mazullo argued that Cobain’s aggressive music and superstar status in the early 1990s for many people brought into the public consciousness a generational conflict between “Generation X” and the “Baby Boomers.” Nirvana’s confrontational music resonated with Generation X, who felt that the generation that directly preceded them, the Baby Boomers, had raised them in a system that could not provide the the pathways to happiness and prosperity that were promised to them by the idealism of post-war America. Mazullo quotes Sarah Ferguson, a journalist, who published an article after Cobain’s suicide saying that, “the hit ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ was… a …resounding fuck you to the Boomers and all the false promises they saddled us with.” Following Cobain’s suicide in 1994 “every major print venue in the country ran obituaries and commentaries on Cobain’s heroic cultural role,” and “suicide hotlines were established across the country,” because there was an immediate fear of copycat suicides. Lorraine Ali writing for the New York Times chalked up the significance of Cobain’s death to the generational tension that allowed Nirvana to sell “millions of albums to peers who can relate to their rootless anger.” Here, Ali uses the word “peer” to describe the people who purchased Nirvana’s music, not “fans,” because to many listeners of Nirvana, Cobain was one of them, not just a rockstar. Cobain, plagued by many of the same ills that the listeners of his music were, triggered a deep emotional response from others in his generation who suffered from drug addiction, depression, chronic illness, and childhood trauma, like himself. For many young people in his generation, those characteristics of his personality and the social conditions in which he published his music were as important as the songs he wrote and the tracks that he recorded, and it is a big part of the reason why Nirvana’s music had immense and immediate commercial success.

Punk rock, a subgenre of rock that influenced Nirvana, actively resisted the mainstream and commercial entertainment industry. According to Dawson Barrett, punk engaged in “direct action” politics and “built its own elaborate network of counter-institutions, including music venues, media, record labels, and distributors,” that acted as “cultural and economic alternatives to corporate entertainment industry,” instead of trying to “[petition] the powerful for inclusion.” Which, Barrett argues, “should also be understood as sites of resistance to the privatizing agenda of neoliberalism,” because creating their own institutions and economic circuits was a conscious political choice to not participate in the dominant cultural economic ideology and social system. Barrett’s article, DIY Democracy: The Direct Action Politics of U.S. Punk Collectives, asserts that punk culture descended from “New Left Principles,” like “consensus-based decision-making, voluntary participation, and relatively horizontal leadership structures,” in direct defiance of the neoliberal ideology that evolved alongside punk in the United States. The punk rock musicians who engaged in “DIY democracy” had no desire to exist within the neoliberal commercial entertainment structure and built their own structures. Punk musicians created new modes of living to accompany their art. The development of punk music is also a history of a counter culture openly defiant of materialism, consumer culture, and mainstream political thought.

Václav Havel, photograph by Jiří Jiroutek

The Czechoslovakian rock movement in the 1970s also created “counter-institutions.” The existence of these counter-institutions and the desire to create modes of living outside of the state-accomodated social structures of the communist regime came to a head in 1976 when the members of a rock band called “The Plastic People of the Universe,” were put on trial and convicted for their music and their concerts. The state believed that the music and community of musicians put Czechoslovakia at risk. The trial, and the verdict, were the catalysts for the creation of the Charter 77 organization in Czechoslovakia. Charter 77, made up of the Czech intelligentsia who feared that the state could and would remove their freedoms of speech and assembly, was instrumental in bringing down the communist regime in the Velvet Revolution in 1989. Vaclav Havel, a founding member of Charter 77 and a spectator at the trial of The Plastic People of the Universe, wrote in his highly influential essay “The Power of the Powerless,” that the trial between the communist judicial system and the rock band was a confrontation between “two differing conceptions of life.” The state feared that the rock band’s music and concerts could undermine the solidarity and the morality of the state. Havel criticized the state’s viewpoint and actions as an “attack on the very notion of living within the truth, on the real aims of life.” The state according to Havel, acting from fear, took judicial measures to prevent the rock band from living and acting according to principles of freedom of expression and individual choice, because the very act of “living within truth” put the rigid totalitarian ideology of the Czechoslovakian state into question.

Havel identified that the Plastic People of the Universe had created their own counter-institutions, and he defined them as a “parallel polis.” In the Czechoslovakian state structure, Havel theorized that rock bands, and dissident groups in general, created their own organizational and economic structures in order to perpetuate their existence, and these “parallel polis” structures developed naturally as a response to the state rigidity and limitations of communist Czechoslovakia. Creating and maintaining these “parallel polis” structures was the only way that these musicians could live out their truth, playing the music that they wanted to play and living out the communal experiences that they wanted to have. The parallel polis that The Plastic People of the Universe created had two enormous effects on Czechoslovakian society: 1) it forced the state to take judicial action and punish an entity that they perceived as a threat, which began a new crackdown on elements in Czechoslovakia that the state perceived to be subversive, and 2) inspired part of the intelligentsia to found the Charter 77 organization in order to protect the rights of free speech and criticism. The Plastic People of the Universe inspired immediate action on both sides of a political conflict. While Cobain embodied a generational conflict, the Plastic People of the Universe’s embodied a political one.

The ontologies of rock music developed by Gracyk, Kania, and Bruno all abstract rock music from the social and political conditions that surround the art. At best this is incomplete, but at worst it is misleading. The aforementioned examples elucidate rock music’s tendency to embody social and political conflict, and in the case of The Plastic People of the Universe, inspire action on both sides of a political conflict. Kurt Cobain became a spokesman for his generation not only because of his ability to write popular songs and record popular tracks, but also because he was seen by some as a martyr-like figure. Punk rock musicians often denied mainstream consumer culture and replaced it with counter-institutions and grassroots organization to avoid having to work within the neoliberal economic system. These aspects of rock music are as important to our understanding of its history as the fact that the artform is primarily mediated from the artist to the recipient through sound recording. To move toward a more comprehensive ontology of rock, the cultural and political symbolism that rock music and its practitioners embodied should be taken into account.

Leave a Reply