By guest contributor Christopher Porzenheim

Even the smallest display of virtuous conduct immediately inspires us. Simultaneously we: admire the deed, desire to imitate it, and seek to emulate the character of the doer. […] Excellence is a practical stimulus. As soon as it is seen it inspires impulses to reform our character. -Plutarch. [Life of Pericles. 2.2. Trans. Christopher Porzenheim.]

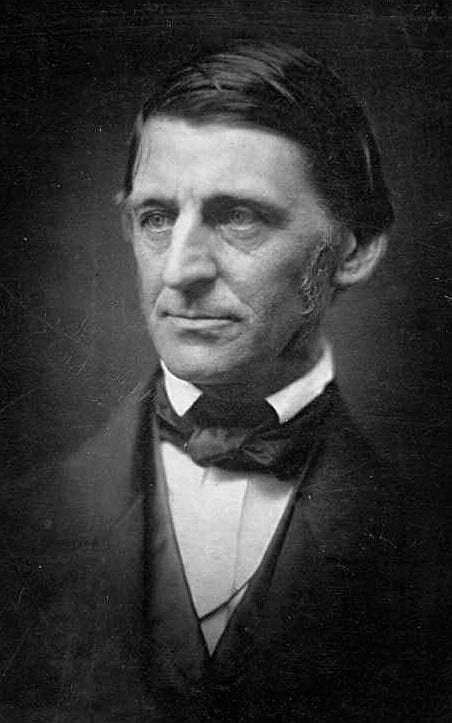

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson has been characterized as a transcendentalist, a proto–pragmatist, a process philosopher, a philosopher of power, and a even “moral perfectionist.” While Emerson was all of these, I argue he is best understood as a philosopher of social reform and virtue ethics, who combined Ancient Greco-Roman, Indian, and Classical Chinese traditions of social reform and virtue ethics into a form he saw as appropriate for nineteenth-century America.

Reform, of self and society, was the central concern of Emerson’s philosophy. Emerson saw that we as humans are by nature reformers, who should strive to mimic the natural and spontaneous processes of nature in our reform efforts. As he put in one of his earliest published essays, Man the Reformer (1841):

Reforming oneself, with models of moral and religious heroes from the past, and through one’s own example, others, and eventually society itself, was the idea at the center of Emerson’s philosophy. He would often echo the virtue ethicist Confucius’s (551–479 BCE) advice that “When you see someone who is worthy, concentrate on becoming their equal; when you see someone who is unworthy, use this as an opportunity to look within yourself [for similar vices].” [A.4.17.]

For example, in the essay History (1844), Emerson wrote that “there is properly no history; only biography” and argued that this “biography” exists to reveal the virtues and vices of exceptional individuals character:

For Emerson, the task, of all literature and history, was offering people enjoyable and memorable examples of virtue and vice for them to pattern their own character, relationships, and life by. “The student is to read history, actively and not passively; to esteem his own life the text, and books the commentary.” History is a biography of our own potential character.

The logical result of these beliefs, was Emerson’s later work, Representative Men (1850) a collection of essays which provided biographies of “wise men,” “geniuses” and “reformers” each illustrating certain virtues and vices for his readers to learn from.

Plato for example, represented to Emerson the virtues and vices of a character shaped by philosophy, Swedenborg a mystic, Montaigne a skeptic, Shakespeare a poet, Napoleon a man of the world, and finally Goethe, a writer.

Representative Men was in part a direct response to the work of Emerson’s friend Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes and Hero Worship & The Heroic in History (1841). But both men’s works shared a common ancestor well known to their contemporaries, Plutarch’s Parallel Lives.

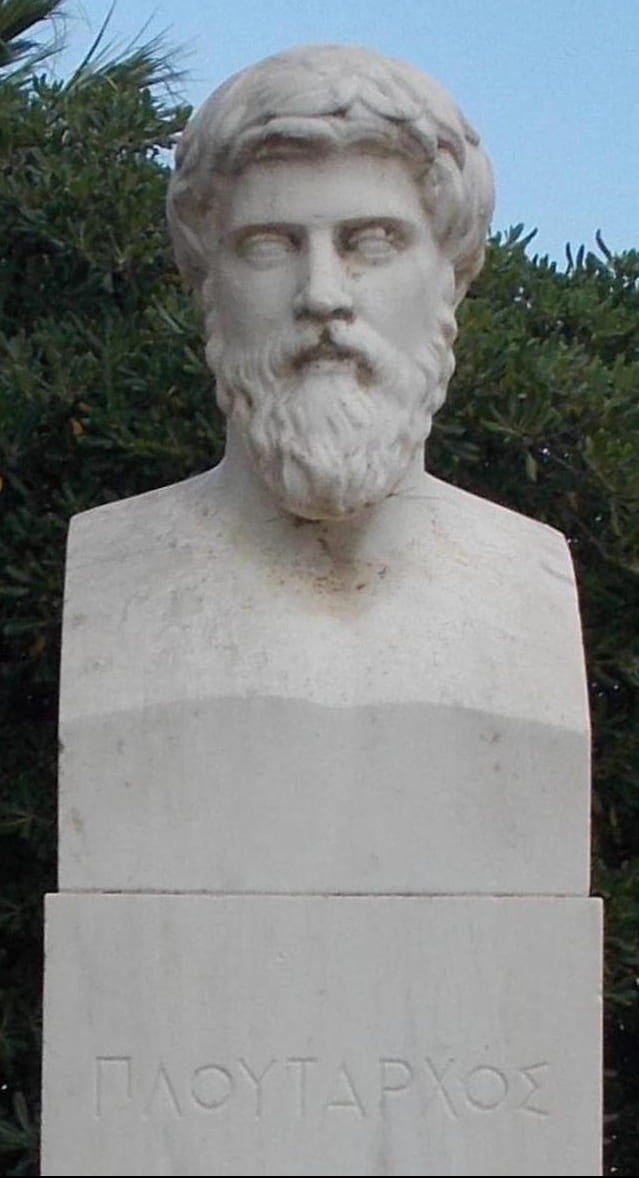

A bust of Plutarch in his hometown of Chaeronea, Greece

Plutarch (46-120 CE), a Greco-Roman biographer, essayist and virtue ethicist, who was deeply influenced by Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoic and Epicurean philosophy, wrote a collection of biographies (now usually called The Lives) and a collection of essays (The Morals) which would both serve as a models for Emerson’s work.

Plutarch’s Lives come down to us as a collection of 50 surviving biographies. Typically in each, the fate and character of one exceptional Greek individual, is compared with those of one exceptional Roman individual. In doing so, as Hugh Liebert argues, Plutarch was showing Greek and Roman citizens how they could play a role in shaping first themselves, and, through their own example, the Roman world. In an era that perceived itself as modern, chaotic, and adrift from the past; Plutarch showed his readers how they could become like the heroes of the past by imitating their virtuous patterns of conduct.

Plutarch’s Lives provoke moral questioning about character without moralizing. They give us a shared set of stories, some might say myths, by which we can measure ourselves and each other other. They show in memorable stories and anecdotes what is (and is not) worth admiring; virtues and vices.

We might, for example, admire Alexander the Great’s superhuman courage. But, what of the time he “resolved” a conflict between his best friends by swearing to kill the one that started their next disagreement? Or, even worse, what of when he executed Parmenion, one of his oldest friends? The Lives are not hagiographies.

Instead, they are mirrors for moral self-cultivation. For Plutarch, the “mirror” of history delights and instructs. It reflects the good and bad parts of ourselves in the heroes and villains of the past. The Lives are designed as tools to help reform our character. They help us see who we are and could become because they portray the faces of virtue and vice, as Plutarch put it at the start of his biography of Alexander the Great:

I do not aim to write narratives of events, but biographies. For rarely do a person’s most famous exploits reveal clear examples of their virtue and vice. Character is less visible in: the fights with countless corpses, the greatest military tactics, and the consequential sieges of cities. More often a person’s character shows itself in the small things: the way they casually speak to others, play games, and amuse themselves.

I leave to other historians the grand exploits and struggles of each of my subjects – just as a painter of portraits leaves out the details on every part of his subject’s body. Their work focuses upon the face. In particular, the expression of the eyes. Since this is where character is most visible. In the same way my biographies, like portraits, aim to illuminate the signs of the soul. (Life of Alexander. 1.2-1.3. Trans. Christopher Porzenheim)

Eighteenth-century European depiction of Confucius

Emerson was in firm agreement with Plutarch about the relationship between our everyday conduct, virtue and character. In Self Reliance (1841), he wrote that “Character teaches above our wills. Men imagine that they communicate their virtue or vice only by overt actions, and do not see that virtue or vice emit a breath every moment.” This idea is axiomatic for Emerson. Hence why, in his essay Spiritual Laws (1841), he quotes Confucius’ claim: “Look at the means a man employs, observe the basis from which he acts, and discover where it is that he feels at ease. Where can he [his character] hide? Where can he [his character] hide?” [A.2.10] For Plutarch and Emerson, our character is revealed in the embodied way we act every moment; in the way we relate to others – in our spontaneous manners, etiquette, or lack thereof.

As Emersons approval of Confucius suggests, Plutarch’s Lives, and Greco-Roman philosophy in general was merely one great influence on Emerson ideals of self and societal reform. It is to these other influences, from Confucian philosophy in particular, that we will turn in a subsequent post, in order to clarify Emerson’s philosophy of virtue ethics and social reform.

Christopher Porzenheim is a writer. He is currently interested in the legacy of Greco-Roman and Classical Chinese philosophy, in particular the figures of Socrates and Confucius as models for personal emulation. He completed his B.A. at Hampshire College studying “Gilgamesh & Aristotle: Friendship in the Epic and Philosophical Traditions.” When in doubt he usually opens up a copy of the Analects or the Meditations for guidance. See more of his work here.

1 Pingback