By Robert Greene II

“Remember the ladies.” This is a line from Abigail Adams’ famous letter to her husband, John Adams, defending the idea of rights and equality for women. “Remember the ladies,” however, could easily also serve as the defining idea of modern African American intellectual history. Many historians of the African American intellectual tradition have taken great pains to emphasize the importance—indeed, the centrality—of African American women to that intellectual milieu. At the same time, other fundamental questions have been raised of not just who to privilege in this new turn in African American intellectual history, but what sources are appropriate for intellectual history. Finally, the ways in which the public remembers the past animates newer trends in African American intellectual history. In short, African American intellectual history’s recent historiographic turns offer much food for thought for all intellectual historians.

The field of African American intellectual history has come a long way since the heyday of historians August Meier and Earlie E. Thorpe, both prominent in the then-nascent field of African American intellectual history in the 1960s. Meier’s Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915 and Thorpe’s The Mind of the Negro: An Intellectual History of Afro-Americans were both written in the 1960s and set the standard for African American intellectual history for decades to come. Both books were focused heavily on male intellectuals, however. As such they both set the standard for the field and, along with so much of African American history up until the late 1980s, left out the important voices of many African American women.

The rise of historians like Evelyn Higginbotham in the early 1990s ushered in new ways of understanding the intersection of race and gender through American history. Her book Righteous Discontent (1992) and essay “African American Women’s History and the Metalanguage of Race” (1992) both provided templates for how to easily meld women’s history and African American history into texts that became essential works of understanding the past through viewpoints and sources normally ignored by most male historians.

Today, the field of African American intellectual history has been influenced by the evolution of several related fields: African American women’s history and Black Power studies. Both fields have attempted to both overturn older assumptions about African American history and do so by focusing on previously marginalized sources and historical figures. Much of the recent historiographic trends in African American history—namely, a deeper understanding of Black Nationalism and its relationship to broader ideological trends in both Black America and the African Diaspora—would not have been possible without both a deeper understanding of the importance of gender to African American history, and a willingness to expand the definition of who are “important” intellectuals “worthy” of study.

In just the last year alone, numerous books about the intersection of Black Nationalism and gender have challenged earlier assumptions about the histories of both fields in relationship to African American history. Both Keisha Blain’s Set the World On Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and Ashley D. Farmer’s Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (UNC Press, 2017) stretch the time period in which historians should understand the origins of Black Power—getting further away from just understanding the 1960s-era context and situating Black Power and larger Black Nationalist trends in a long era of resistance and struggle led and strategized by African American women.

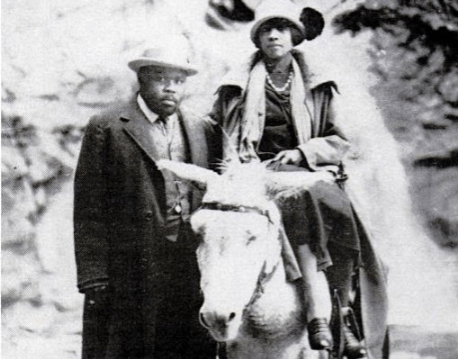

Set the World on Fire follows up on other works about the Black Nationalism of the 1920s, arguing that it did not end with Marcus Garvey’s deportation from the United States in 1927. Instead, argues Blain, it was women such as his spouse Amy Jacques Garvey who kept Black Nationalist fervor alive across the United States. Meanwhile, Farmer’s book shows how the ideas of women associated with the Black Power movement of the 1960s owe a great deal to the longer arc of radical black women’s history in the twentieth century—from the agitation of black women within the Communist left of the 1930s and stretching well into the 1970s and 1980s. For Farmer, the history of a radical black nationalism does not end with the collapse of the Black Panther Party in the late 1970s.

Meanwhile, other trends within African American intellectual history point to the utilization of previously ignored or forgotten sources to provide a deeper understanding of the past. Derrick White’s The Challenge of Blackness: The Institute of the Black World and Political Activism in the 1970s (University Press of Florida, 2011) argues for diving deeper into relatively recent African American intellectual history to provide a fuller picture of the post-Civil Rights Movement era. For White, the African American think tank was an important ideological clearing house for not just African Americans, but the broader Left in the 1970s.

A third movement within the field is the study of African American history itself. Pero Dagbovie has led the way in this, writing several key works detailing the rise of African American history over a broad timespan. Works such as African American History Reconsidered (University of Illinois Press, 2010) and The Early Black History Movement (University of Illinois Press, 2007) detail not only historiographic trends in the field, but the ways in which the institutions necessary for the growth of African American history were born and nurtured against the backdrop of Jim Crow segregation.

Finally, the importance of understanding memory to African American intellectual history has changed the way African American intellectual historians think about the intersection of ideas with public discourse. In reality, much of the understanding of “memory” by African American intellectual historians concerns forgetting by the vast public. Books such as Jeanne Theoharis’s A More Beautiful and Terrible History (Beacon Press, 2018) emphasizes how much of the American mainstream media—along with most politicians—have been complicit in hiding the deeper, more complicated histories of the Black freedom struggle in the United States.

African American intellectual history offers plenty of new opportunity for scholars interested in linking intellectual history to other sub-fields. African American activists and intellectuals never existed in a vacuum, whether geographic or ideological. They made alliances with a variety of groups and forces, all for the sake of freedom across the African diaspora. The new turns in African American intellectual history reflect this aspect of black history.

Robert Greene II is a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Claflin University. He studies American intellectual and political history since 1945 and is the book review editor for the Society of US Intellectual Historians.

Featured Image: Amy Jacques Garber, with her husband, Marcus Garvey.

September 24, 2018 at 9:40 am

Reblogged this on Project ENGAGE.