By Gloria Yu

Whether a man is wise can be gathered from his eyes. So thought the Anglican bishop Joseph Hall in his 1608 two-volume collection of character sketches, Characters of Vertues and Vices. The wise man, Hall advised, “is eager to learn or to recognize everything but especially to know his strengths and weaknesses…His eyes never stay together, instead one stays at home and gazes upon himself and the other is directed towards the world…and whatever new things there are to see in it” (quoted in Whitmer, The Halle Orphanage, 77). The wise man’s eyes are the entry points of both self-knowledge and worldly knowledge, and their divergent gaze betrays his catholic curiosity.

The eye plays a central role in two recent snapshots from the history of Western pedagogy that find it productive to ground the historical construction of norms for knowing in educational contexts. Kelly Joan Whitmer’s The Halle Orphanage as Scientific Community: Observation, Eclecticism, and Pietism in the Early Enlightenment (Chicago, 2015) examines the scientific ethos that permeated and vitalized the premier experimental Pietist educational enterprise of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Orit Halpern’s Beautiful Data: A History of Vision and Reason since 1945 (Duke, 2015) offers a genealogy of contemporary obsessions with “data visualization,” their ontological and epistemological consequences, and the pedagogies that spurred them. Both works centralize the eye as the object of training and discipline. Both accounts trace the pedagogical principles behind the ways in which seeing must be learned, extending the functions of the visual apparatus beyond the role of passive reception into an active mode of evaluating and constructing. Seeing, in these histories, is imbued with cognitive powers so as to be near congruent with knowing itself. Considering these two works together prepares us to use the recurring motif of the trained eye as an opportunity for gauging future directions for histories of pedagogy.

Whitmer informs us that descriptions like the one above of the ‘character of the wise man’ were regularly incorporated into the curriculum at the Halle Orphanage’s schools for the purpose of training a particular way of seeing. The Orphanage’s founder, August Hermann Francke, believed these character sketches could “awaken” in children a love of virtue so that they might emulate the figures depicted. The end goal was the cultivation of an “inner eye,” or “the eye in people,” which Francke equated with prudent knowledge [Klugheit] and pious desires. Indeed, a pedagogy of seeing permeated Francke’s administration of the Orphanage. The training of the inner eye was based on the honing of an array of observational practices that engaged senses beyond just the visual. On one level, visual aids such as scientific instruments (e.g. the camera obscura, air pumps), wooden models, and color-coded maps cultivated tactile, spatial, and relational knowledge. In Francke’s correspondence with the mathematician Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, the microscope figures as a particularly apt tool for lessons in seeing since it enhanced understanding of the configuration of parts and wholes while also providing the opportunity to reflect on the faculty of seeing itself. Through observing how minute changes in light transformed one’s image of an object, one could discern the possibilities and limits of human perception. On another level, visual aids, like the models of the geocentric and heliocentric heavenly spheres specially commissioned for the Orphanage, enhanced cognition and yielded spiritual benefits by teaching students how to behold incompatible representations of the world and to reconcile them. The Orphanage taught a manner of “seeing all at once,” wherein the eye was considered a “conciliatory medium” that could aid in transcending interconfessional disagreements.

For Whitmer, seeing and the eye operate as metaphors for perception, understanding, and cognition writ large, at times even as the privileged site for accessing divine truths. Notable is her use of the singular. If it is through seeing in a broad sense (materially, affectively, cognitively) that we encounter the world and acquire knowledge of it, it is the eye that mediates this encounter. From the ancient origins of the evil eye, to Avicenna’s comparison of the eye to a mirror, to the early modern possibility that a wrong stare could compel an accusation of witchcraft, the eye—and not only in the Western tradition—has perhaps always been overdetermined. Its activity always transcends the physiological processes behind mere visual perception. It was after all in tempting Eve to take from the tree of knowledge that the serpent said, “For God knows that in the day you eat of it, your eyes will be opened” (Genesis 3:5).

“Vision,” as Halpern notes, “is thus a term that multiples—visualization, visuality, visibilities” (24). Dexterity in handling the conceptual differences of this plurality allows Halpern to explain how, since the end of World War II, we have come to bestow such a capacious range of talents to our ocular organs. In the context of increasing computational and data scientific approaches in information management, architecture and design, and the cognitive sciences, Halpern argues, vision has taken on a highly technicized form, meditated by screens, data sets, and algorithms that fundamentally expand the epistemological prowess of perception. In particular, postwar cybernetics and design and urban planning curricula had a hand in transforming the ontology of vision. Cybernetics’s preoccupation with prediction, control, and crisis management foregrounded information storage and retrieval and, thus, transformed the eye into a filter and translator of sorts, selecting relevant information for storage within a constant flow based on algorithms for pattern recognition. Whereas the eye at the Halle Orphanage dwelled on contradictory images, the eye of twentieth-century cybernetics constantly made choices.

The works of these authors suggest the advantages of approaching questions central to intellectual history—concerning the transmission, unity, and cultural impact of ideas—from the perspective of histories of pedagogies. Analyzing pedagogy allows Halpern to trace how philosophical ideas were transformed into teachable principles and how a certain paradigm of vision was promulgated through the materiality of our media environments. In her narrative, industrial designers, drawing from cybernetics, developed an “education of vision” grounded in “algorithmic seeing” (93). Here, vision mimicked the activity of a pattern generator: rather than representing the world, this ‘new’ vision captured the multitude of ways something could possibly be seen. Vision was about scale and quantity, about producing as many representations and recombinations of the visual field as possible. No longer could any pedestrian see the world; one had to learn through credentialed training to be considered an “expert” in vision (94). The screen-filled “smart” city of Songdo, South Korea is an embodiment of this paradigm, where older ways of seeing lose out to a vision continually registering and ordering human and environmental metrics toward the goal of “perfect management and logistical organization of populations, services, and resources” (2).

Furthermore, histories of pedagogy, whether central to a project (as in Whitmer’s case) or part of a larger investigation measuring the scale of cultural transformation (as in Halpern’s), can answer questions that animate the intersection of history of knowledge, history of science, and historical epistemology. These fields have offered a robust vocabulary for interrogating the historical contingency of observation and objectivity; the historical, social, and cultural criteria for knowledge; and the methodological goals and tactics involved in fortifying scientific persona. Beside the fact that pedagogy is a science and set of practices specifically concerned with communicating knowledge, Whitmer and Halpern show that, in addition to articulating what it means to learn in certain moments and institutional contexts, pedagogical theories can contain latent or overt temporalities, subjectivities, and modes of vision that deepen our understanding of what in the past has made knowledge count as knowledge.

Yet, histories of pedagogies have even more fruits to bear. If earlier histories focused on matriculation rates, student body demographics, and the longevity of institutions, these two works prove future research capable of taking on the relationship between science and religion, the convergence and divergence of intellectual traditions, the crests and troughs in the history of humanism, and episodes in the centuries long contemplation of what it means to be human. Future research would follow precedent histories of pedagogy, not least the scholarship of our discussant, in treating sensitively the gaps between ideals of education and their execution, the slips between the social and political aims of education and their imperfect applications (Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine, From Humanism to the Humanities: Education and the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Europe). That pedagogy is a tradition embedded in text, reliant on practices, and crucial to the scaffolding of intellectual traditions places the excavation of its pasts well within the purview of intellectual historians.

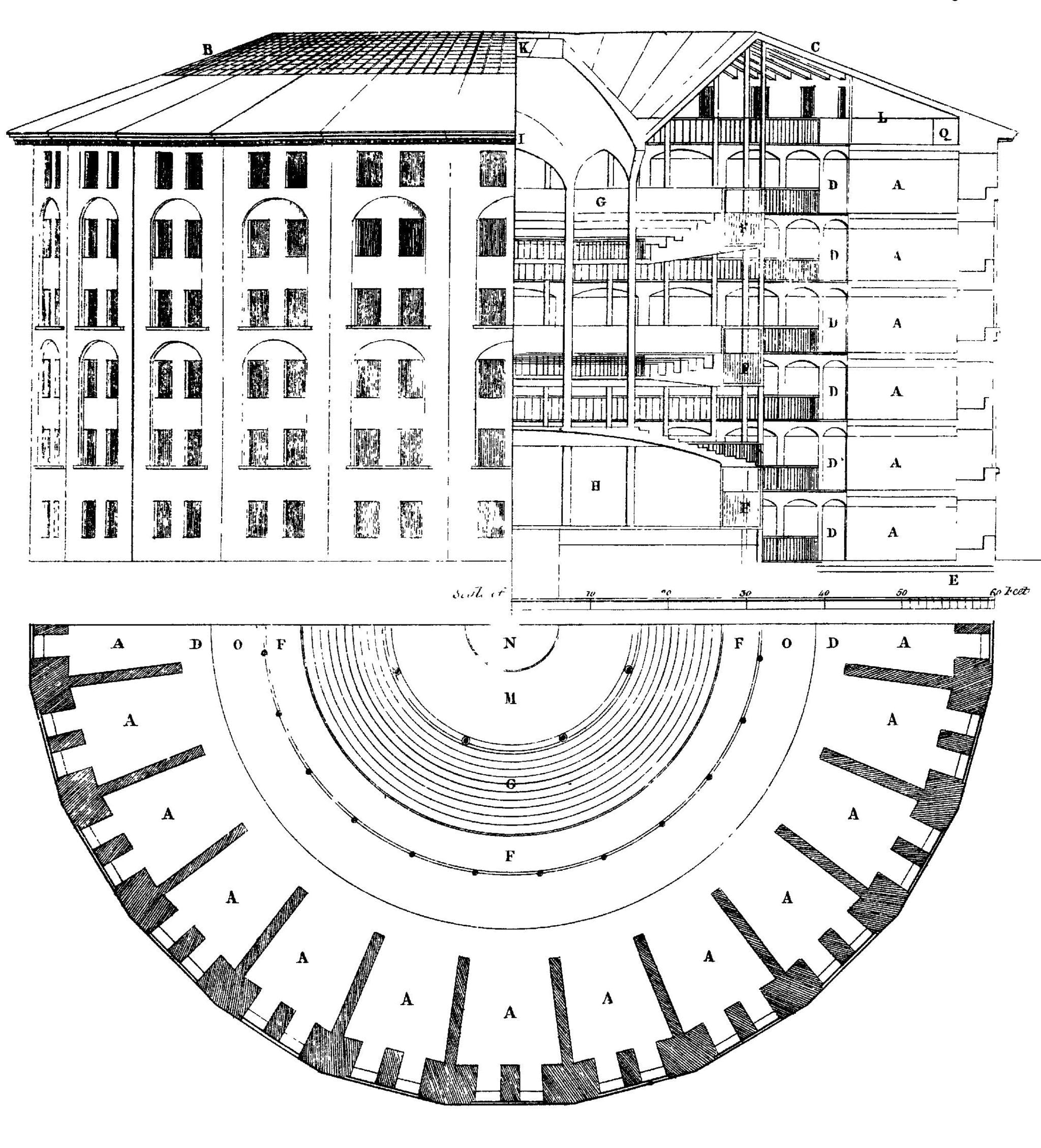

One last note on the eye. Mention of training the eye calls to mind the familiar narrative that forms of discipline often get inscribed on bodies. While this may be true, that there are multiple histories of pedagogy suggests the probability that we are trained in numerous contexts, at different times in our lives, and in potentially incompatible ways in how to see and how to know. It is possible, then, to become at once wise and childish, to become discerning in one way and docile in another. As to whether we are overwhelmingly determined by systems of power and whether there are multiple systems at play, I answer with an optimistic agnosticism that leaves open the question of the place of freedom. I rely on the vagueness of the term freedom here to underscore that the day-to-day exercises in learning may fail to yield desired results or, even when they do, may be useful in ways other than intended. For the researcher willing to question the Foucaultian schema that binds discipline with docility, the histories of pedagogy—of pedagogies with a range of reaches, in quiet pockets of Europe or in grander governmental programs—can be treated as an approach capable of accommodating histories of discipline that remains sensitive to the rough trajectories of learning. If the Panopticon’s surveilling gaze, both omnipresent and invisible, inspires the self-policing of behavior, how does the prisoner see when he looks back?

Gloria Yu is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research focuses on the history of psychology and the concept of the will in nineteenth-century Europe. She thanks David Delano, Elena Kempf, and Thomas White for their incisive comments on earlier drafts.

Featured Image: Joseph Hall might find the eyes, more than the books, to be the prominent ‘accessory’ in Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Book (1530s). While the left eye is directed outward, ‘towards the world’, the gaze of the right eye (our left) seems unfocused on what is directly before it. It is not a look that invites sustained eye contact with the viewer; rather, an apparent disinterestedness suggests that the man’s attention is elsewhere. The aimless stare is a marker of a gaze turned inward. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

2 Pingbacks