Here are some highlights from what our editors have been reading this month—with another installment next weekend. Let us know what you’ve been reading, or if one of your favorites is here.

Sarah

Elaine Mokhtefi moved to Paris from New York in 1951. She hoped that there she might ‘drink at the fountain of the past’ through immersion in the literary and cultural capital that had drawn so many revolutionary luminaries. As it happened, she became one of those revolutionaries herself, swept up in the anti-colonial movements of the 1950s. When she returned to New York in 1960, it was to work in the provisional headquarters of the unrecognised Algerian government. Two years later, after Algeria finally won its independence from France, Mokhtefi moved to Algiers to take part in building the new nation. Her memoir, Algiers, Third World Capital, is a testament to her time there. It is filled with tantalising recollections of Mokhtefi’s interactions with pivotal activists such as the psychologist and writer Frantz Fanon and the Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver. At the risk of sounding dictatorial, it is an unmissable read.

Elaine Mokhtefi

I’ve been meaning to revisit Achille Mbembe’s Critique de la raison nègre since I finished my dissertation and this summer seemed the perfect time to do so. The work remains an indispensable guide to the genealogy of the historical category of blackness, bringing together both francophone and Anglophone postcolonial thinking. It has also just come out in English translation by Laurent Du Bois. I was particularly enamoured by Du Bois’ introductory lines to the book. They encapsulate both his philosophy of translation and the intellectual elegance of Mbembe’s work. I could do no better than to reproduce them here: ‘If a language is a kind of cartography, then to translate is to transform one map into another. It is a process of finding the right symbols, those that will allow new readers to navigate through a landscape. What Mbembe offers us here is a cartography in two senses: a map of a terrain sedimented by centuries of history, and an invitation to find ourselves within this terrain so that we might choose a path through it— and perhaps even beyond it’ (ix).

I’ll finish this month’s recommendations with another firm declaration: everyone should read Imaobong Umoren’s Race Women Internationalists. It came out in May this year and is a brilliant reconstruction of the lives and activism of three incredible women: the American Eslanda Robeson; the Martinican Paulette Nardal and the Jamaican Una Marson. From the 1920s through to the late 1960s, these three women traversed the globe and built activist alliances against racism, imperialism and fascism. Umoren’s meticulous scholarship not only enhances our understanding of these women but gives great insight into the dynamics of black internationalism in the mid-twentieth century.

Brendan

Just what on earth is natural for humans to do? Is it natural for us to tuck and barter? To dominate and kill? To cheat on our spouses? To marry at all? To be religious? To eat wheat and drink milk or almonds and bacon? To run barefoot? A big trend today is to search for a moral example in our primate past. You can see this in hip American in our paelo diets and barefoot running shoes. You also see it in the reactionary right’s fundamentalist appeals to strict gender norms and racial purity.

Most of these treatments promise that if we could just see the moment of our emergence as a species, then we could know what kind of society we should have today. It’s troubling that the picture that often emerges is, as Paul Seabright says, one of “a shy, murderous ape.” Our closest genetic relatives save the bonobo, the chimpanzee, have frequent male violence. Some reports from hunter gatherer societies show high murder rates. And most evolutionary psychology agrees. Men kill. They rape. They wage war. Is this our nature? There is a book called Demonic Males whose cover portrays a bestial chimera, horned, one-half snarling human, one-half snarling chimp.

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Mothers and Others; The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011).

But in her recent book, Mothers and Others, Sarah Blaffer Hrdy presents a very different image of pristine humanity. We are not violent at all. In fact, the puzzle is how we came to be so peaceful. Consider the fact that we very rarely feel the urge to kill anyone on an airplane, even though people on airplanes regularly commit very killable offenses like eating blue cheese next to you, or stealing your arm rest. Chimps, or any other great ape, wouldn’t stand for that—they would be red in tooth and claw before the flight touched down in Pittsburgh. Why? Why are we able to cooperate so well?

To explain this deep history of the pro-social emotions—what Hrdy calls our ‘emotional modernity’—Hrdy look at that other peculiarity of humans: our weird life histories. We have long and very helpless childhoods (a baby human needs perhaps a million calories to grow to an adult human), and long reproductively-useless old ages. The extended childhood of humans means that no single person—nor even a devoted couple—can conceivably care for a child on their own. We need help. And in our distant past, children were raised by whole communities, not by pairs of dutiful hunter-gatherer wives and husbands. Allo-parents (non-parent child-rearers who may or may not be related to the child in question) pick up children, take care of them, and often share food with them. In technical terms, humans are cooperative breeders. This also explains our extended non-reproductive dotages. Grandmothers and grandfathers are important allo-parents. But mostly grandmothers. In some hunter-gatherer societies, the presence of a grandmother can cut child mortality in half. Tellingly, a chimpanzee mother will not let even her own mother touch her child except in the direst circumstances. This makes sense, as a key cause of infant death are other chimpanzees. But human mothers are fine with friends, family members, and annoying uncles picking up their defenseless newborns from the very moment of birth.

A young human child raised by parents and friends and grandparents and aunts and uncles, needs to be able to read the emotions of the people around them, to know who will take care of them, and cutely manipulate allo-parents to parent them. At the root of human society, then, Hrdy puts not a snarling chimp, but a cooing child.

Pranav

Early modern sermons are some of the most important primary sources that I work with. While I tend to read them primarily to ascertain the intellectual commitments of the preachers, several scholars have now begun to study them within a wider cultural and commercial context. The results of some of these studies have been nothing short of fascinating.

John Tillotson

Seventeenth and eighteenth-century clergymen, both Anglican and nonconformist, preached regularly and intensively. They wrote sermons on a wide variety of topics and constantly refined them to suit the occasion and the needs of their respective audiences. While many sermons remained in manuscript form, others were printed in folios or as individual pamphlets. They constituted one of the primary means of intervening in political and theological controversies. As such, their impact on early modern religious and political debate was immense. Especially towards the end of the seventeenth-century, sermons became some of the best-selling printed materials. In the eighteenth-century, the copyright for the sermons of John Tillotson, former Archbishop of Canterbury, was sold for an enormous sum of £2,500.

Amongst the many studies on preaching and sermons in recent years, two stand out. Arnold Hunt’s The Art of Hearing: English Preachers and their Audiences, 1590-1640 is an exceptionally detailed study of what was preached from Elizabethan and Jacobean pulpits and how it came to define the religious culture of the time. Hunt deftly analyzes a whole series of manuscript sermons to show how the laity actively engaged with the content of the sermons and how its responses often forced preachers to revise the content. His analysis provides a strong critique of Keith Thomas’s somewhat dismissive thesis that most early modern parishioners lacked the sophisticated of an educated schoolboy. The Oxford Handbook of the Early Modern Sermon can be read with great profit along with Hunt’s study. It contains a number of vivid chapters on various aspects of preaching. Rosemary Dixon’s wonderful essay on printed sermons from 1660-1720 explores the economy of sermon printing and distribution and offers insights into the more commercial aspects of preaching.

These studies, however, are only the start of what appears to be a very exciting engagement with the extremely prolific and, at times, contentious world of early modern preaching and sermons. I look forward to learning more about the subject in the coming years.

Nuala

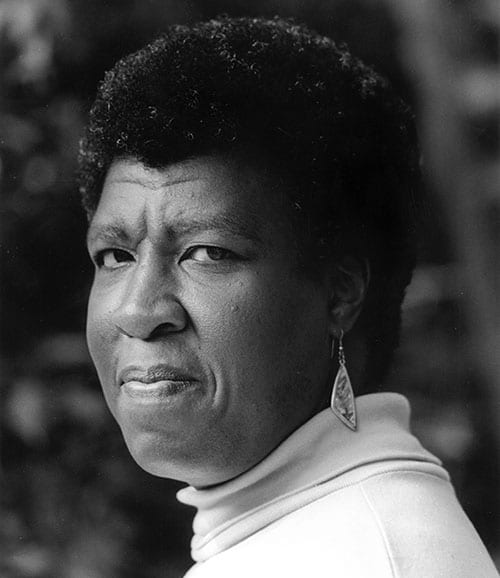

Octavia E. Butler

Queer Feminist Science Studies: A reader (edited by Cyd Cipolla, Kristina Gupta, David A. Rubin, and Angela Willey) begins with a transnational and trans-species approach to journey through a myriad of fascinating inquiries. Twenty essays probe into the intersectional nodes between science and technology studies and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. The authors interventions are significant as their overall goal is to “get inside” categories and ideas that seem self-evident areas of science study. The collection argues that a queer feminist analysis offers a pathway into two main bodies of knowledge about the production, construction and transformation of sexual and gender norms: science and technology. This approach to reading science offers a novel insight into enduring questions such as: What exactly is sex? What ideas and practices need to be tamed to normalization to maintain these fictional hierarchies? How do the categories of gender, sexuality and race interact to hold up these norms? For example, Sarah S. Richardson traces how the X chromosome became assigned as the “Female Chromosome” whilst Aimee Bahng’s treatment of slime molds and science-fiction writer Octavia E. Butler demonstrates how visions of the natural world created spaces for femi-queer conversations. This impressive volume seeks to queer not only the materiality of natural objects in science and technology that became elevated to ontological status but the discourse around such objects.

Spencer

Gilles Deleuze—not a name I am in the habit of citing—called Michel Foucault’s “The Lives of Infamous Men” (1977) a “masterpiece,” and for once I am in full agreement with the Abbot to Félix Guattari’s Costello. Foucault wrote this little essay as the introduction to “an anthology of existences” (76), a proposed volume of brief notices of criminals’ lives from the historical record, chosen because “in the shock of these words and these lives [are] born again for us a certain effect mixed with beauty and fright” (78). The first example he gives is worth quoting in full:

Mathurin Milan, sent to the hospital of Charenton, 31 August 1707: “his madness has always been to hide from his family, to lead an obscure life in the country, to have lawsuits, to lend usurriously and recklessly, to walk his poor spirit upon unknown paths, and to believe himself capable of the very greatest works.” (76)

Spellbinding as such a volume would have been, worthy of a Jorge Luis Borges or a Franz Kafka, this would-be introduction stands on its own merit, as Foucault reflects on his characteristic methods and on the ends of history. He writes that in order for these lives to become visible, “it was […] necessary that a beam of light should, at least for a moment, illuminate them” (79). This beam goes by the name of power: the peculiarities of each rogue in this gallery were recorded because each collided with authority in one way or another. Power, of course, has the same exhausting ubiquity in Foucault as does castration does in Freud or capital in Marx—it is the coin of his realm, the laws of his intellectual physics. And “Lives” contains a moment of charming self-awareness: Foucault writes, “It shall be said to me: that’s just like you, always with the same incapacity to cross the line, to pass over to the other side, to listen to and make heard the language which comes from elsewhere or from below…” (80). The essay goes on to run promiscuously through themes dear to Foucault’s heart: legal discipline, the state, modernity, public and private, sexuality, all channeled through the lettres de cachet, early modern French petitions to the king for the imprisonment of a putative malefactor. Though a collection drawn from this narrow compass was all that came of the project for “an anthology of existence,” even the dream of such a book offers a new window onto the work of calling to life the personages of the past.

September 22, 2018 at 11:16 am

Reblogged this on Project ENGAGE.