By guest contributor Hannah Leffingwell

As I walk through the rain toward the neon sign reading BOOKS, I am aching for some guidance—or what might otherwise be called “theory”—in the likeness of a known name. Having just left the David Wojnarowicz exhibit at the Whitney, I find myself unable to simply return home.

“I’m looking for Susan Sontag,” I tell the man at the bookstore.

“She’s in a graveyard somewhere,” he responds flatly. “She told me once this was her favorite bookstore.”

Affirming at once Sontag’s mortality and her fame, the bookseller answered a question I hadn’t asked in a tone I didn’t expect. It should have been obvious, I thought, that the work of the author existed, while the author herself had ceased to be.

But perhaps the bookseller had a point. I had gone in search of someone, a voice to guide me. And in truth she was nowhere—only words on a page.

Two nights later, alone in my New York apartment, sleep eludes me. I have been reading Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives in the dim light of street lamps through the window. I think perhaps something will be revealed to me this way, attuning myself to the artist’s hallucinatory rambles. He was meant to be a writer, after all, a secret they say was deeply buried in him for years.

I think of the friend who helped to bury him and then took a photograph—for posterity.

I think of everyone we have buried, most lacking the privilege of a wall text, of a frame.

The fear of AIDS imposes on an act whose ideal

is an experience of pure presentness (and a creation of the future)

a relation to the past to be ignored at one’s peril.

Sex no longer withdraws its partners,

if only for a moment from the social.

It cannot be considered just a coupling;

it is a chain, a chain of transmission, from the past.

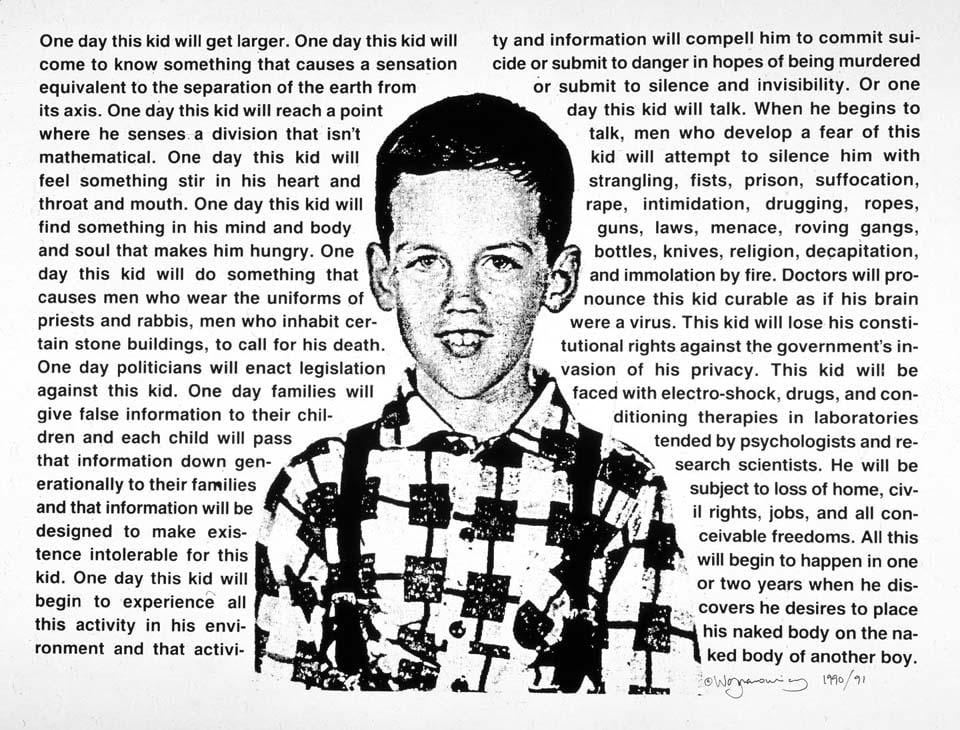

I realize I have come in the wrong way of the exhibit, beginning at the end. It is no gentle transition into skeletons, this way, but death first: full-frontal. In the final gallery, the desperate attempt to say it all—to get it all out. One must work, ironically, to take it all in. And I do, walking slowly from one image to the next, deciphering. The final image, hung along the wall between the end and the beginning, is fittingly that of a child. His toothy grin and earnest features belying a framing of destruction.

Throughout, the black and white invectives deconstruct the framing. Not only the cause of his destruction (his naked body on the naked body of another boy) but the effect (He will be subject to loss).

When I was told that I’d contracted this virus it didn’t take me long to realize that I’d contracted

a diseased society, as well.

There is word and there is flesh but not always where you would expect it. There is black and white, but then there is color and there is whiteness.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Buffaloes), 1994.

I pause to consider the falling buffalo, the burial ground, the reference to a “Native American boy”—scattered through the rest of the room as though part of the same history. I wonder about the ramifications of this reproduction, the taking of something already taken, believing this calculation ends in some kind of double negative. Not the negation of death, per se, but of its pre-invention.

I have my camera in hand, in the spirit of must-not-forgetting, but I find I cannot pull the trigger. Not on the skeletons. But also not on the face, the hands, the feet of Peter Hujar, Wojnarowicz’s dead “brother,” “father,” “emotional link to this world.”

There are some things, I think, that are sacred.

In the Donna Gottschalk exhibit, the next day, I think I will begin at the beginning for once. There is no double entrance this time, only the one. I follow the progression laid out for me—from young to old. I experience aging, this way, as a foregone conclusion. I follow the black and white portraits along the wall as though dragging my fingers along fenceposts, touching the faces of ones more familiar, less obscured.

Donna Gottschalk, Revolutionary Women’s Conference, Limerack, Pa. 1970. Image courtesy of Donna Gottschalk.

A woman naked, in the eyes of her lover, stepping into a bathtub; naked bodies, sleeping, packed like sardines onto a mattress on the floor; the smiling portrait of two lovers on a journey to the coast; a woman’s face half-obscured by the face of her child.

And there is, I think, a not unnoticeable sense of relief. The Man has no place here, no crosshairs aimed. By halfway through I think maybe they have escaped him.

A lesbian is the rage of all women

condensed to the point of explosion. – W.I.W.

It is said that Wojnarowicz skipped town the day he found out he had made it. He left his apartment and headed West. I do not know the reasons, only that his journey felt familiar. The writing on the wall: Young man, disillusioned, goes West in search of Something. A rough translation of the actual wall text that reads: “his rightful place is also among the raging and haunting iconoclastic voices, from Walt Whitman to William S. Burroughs, who explored American myths, their perpetuation, their repercussions, and their violence.”

In the other museum, in a room as small as one of his eleven galleries, the wall text speaks not of Gottschalk’s rightful place, but of her invisibility. Not of an iconoclast, but of a woman “protective of the lives and trust of those who had revealed themselves to her camera.”

There is the question of preservation. Whom to preserve, and how.

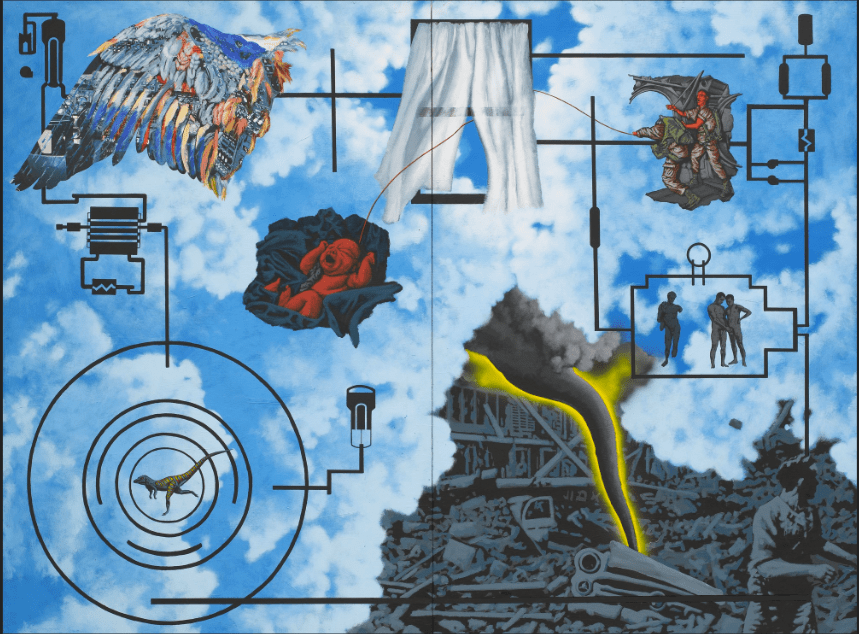

Halfway through his eleven rooms, I study the four elements, beginning with fire and ending with earth. There is the dream, and behind it the reality, and behind that the fear. Not of destruction, I realize, but of nothing. As I trace the red chord out of the baby’s head, through the window, into the hands of the soldier, I notice that something is missing. Not color, or the lack of it, but a sense of its creation. Amidst a succession of childhoods, I realize, there are no mothers, only Gods.

With Gottschalk, there is no shortage of mothers: dead center in a world without men. The story is cleaved in two—youth, age, but in between: an exuberant, collective becoming. Not only the “woman-identified-woman” but her children. And in the center of that center, the whiteness of her body—a Madonna of the lesbian agenda—eyes half-closed as though she hadn’t taken the time to see where she was going. A prophecy not of destruction, but of cleavage: of a movement cleaved by color, or the lack of it.

I am your worst fear / I am your best fantasy

At the end (the beginning) of his art is darkness. A cage of black walls surrounding a papier-maché globe, a burning face. I am told that Wojnarowicz’s series of disembodied heads means something, politically speaking. The outsider. War. Corruption. Perhaps, I think, the blackness is meant to put the other colors in relief—the brightness, an endeavor to prove difference. To prove that he is not-one-of-them.

And it’s not that I don’t believe him or want to. It’s not a matter of believing, really, but of attunement. The hallucinatory rambles have led me somewhere, after all. Not the haunting I was expecting, given the ending of things. But a young man, poised on the brink of his life, playing with masks.

I was wrong about the ending, or lack of it. The assumption being that if the artist lived—survived the work, like Gottschalk—the aching could be for something else. Not guidance, but transmission—the continuation of the known into the unknown.

I was wrong to think that death belonged only to the dead, as I watched first Gottschalk’s friend Marlene, and then her sister Myla disappear in snapshots, becoming a “Xerox” of their former selves, as Wojnarowicz would say of himself in the dying years. Her brother, her sister, her “emotional link to this world”—ravaged, all the same.

Donna Gottschalk, Marlene resting with a beer, Oregon, 1974. Image courtesy of Donna Gottschalk.

At the beginning of the beginning (the end of the end) is not darkness, not light, but illumination. The past by the present. A role reversal in line with all the others.

I have come out, into the light, and they are not who I thought they were. He, the “angel of history,” she, the “brave beautiful outlaw”—both of them catapulted into fame, into tragedy. Neither of them, dead or alive, able to escape the gaze of the present on their past.

I think, perhaps, it was not the repetition of history that kept the artist awake at night.

It was the burden—his, and hers—of making it.

—

David Wojnarowicz: “History Keeps me Awake at Night” closes at the Whitney Museum of American Art on September 30th.

“Brave, Beautiful Outlaws” is open at the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art until March 17th, 2019. There will be a special opening reception featuring the artist on September 29th.

Hannah Leffingwell is a doctoral candidate at New York University. Her research interrogates the intersections of gender, sexuality, race, and class in contemporary French feminism. More of her work can be found on publicseminar.org.

Leave a Reply