By guest contributor Julie van den Hout

Do you ever get an uneasy feeling that something is missing from your wider scholarly realm, even though, on the surface, you have everything covered—and while this nagging sense seems to come and go, you can never quite put your finger on what it is? While I am no psychologist, recent developments have led me to believe that this intangible void could be a lack of seventeenth-century Dutch history in your academic toolkit. This idea came to me after launching the blog, 17thCenturyDutch.com, an online resource for researchers learning to read and translate seventeenth-century Dutch. The site offers learning strategies, tips on grammar and orthography, handwriting guides, sample manuscripts for paleography practice, links to dictionaries and courses, and a forum for posting questions. The blog has been more popular than I imagined and I might know why. Think about it. Have you ever been away from home and overheard Dutch being spoken? The Dutch seem to turn up everywhere. The truth is, the Dutch do not simply seem to be everywhere—they actually are everywhere, and have been for several hundred years. In fact, it is almost impossible to avoid them. And that brings us to the crucial question: Why would you want to? As deeply rooted players in the global marketplace, the Dutch—especially the seventeenth-century Dutch—left an impression, and a paper trail, on almost every continent. Learning to read seventeenth-century Dutch opens the door, not only to the language and history of a small country, but to everywhere the Dutch have traveled and to everything they touched.

The seventeenth-century Dutch impacted history around the globe through trade, exploration, and conquest. On their home continent, commerce took them to the Baltic for grains, to Russia for furs, and to Norway for hardwood. The accessibility to timber coupled with innovations in engineering propelled the Dutch to maritime dominance with the fluytschip, efficient for navigating the shallow river tributaries of Europe with its flat, wide hull and low crew-to-cargo ratio. It was not long before these ships ventured into wider waters, carrying trade goods, building materials, passengers, livestock, and provisions to newly conquered lands. The Dutch East India Company frequented the Indonesian archipelago for highly marketable exotic spices such as nutmeg and cloves. From there, trade took them to India for cotton and silk, to China for tea and porcelain, and to Japan, where they enjoyed exclusive access from the man-made island of Deshima. From Indonesia, explorer Abel Tasman mapped the coast of Australia, eventually touching down in New Zealand. Documents from the Dutch East India Company are now scattered throughout the world, including those occupying 1.3 kilometers of space in the Dutch National Archives.

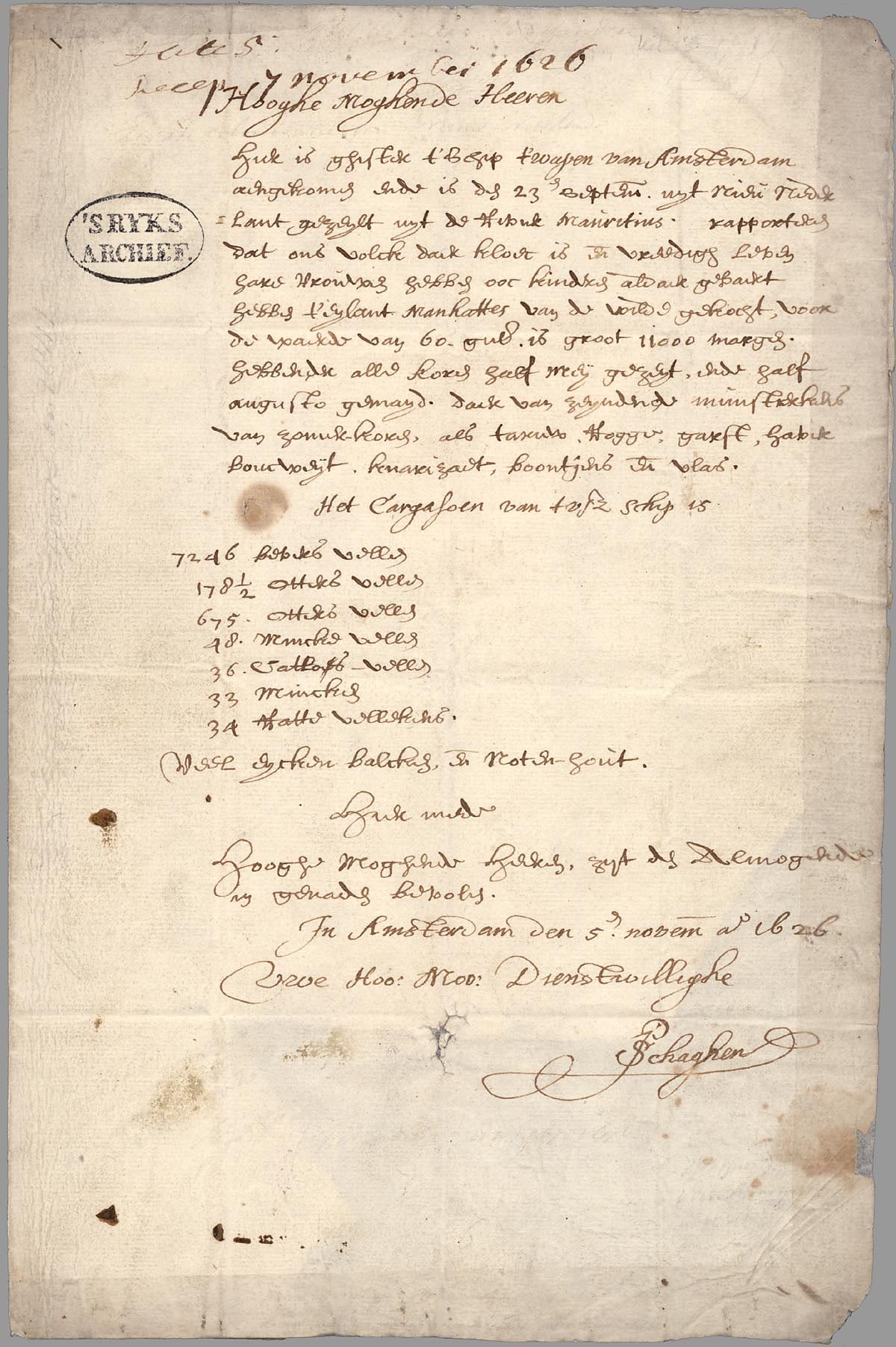

In an attempt to gain control of the spice trade by securing a faster route to Asia, The Dutch East India Company commissioned Henry Hudson to search for the fabled Northwest Passage. Hudson tried four times before failing miserably, cast off in a dinghy by a mutinous crew in the bay that bears his name. An earlier voyage, however, had taken him into the mouth of the Hudson River, where he claimed the area for the Dutch. Though the Dutch did not appreciate this little piece of waterfront property until it was too late, the States General gave a monopoly on the fur trade there to the newly formed Dutch West India Company. Predominantly tasked with disrupting Iberian concerns in the Atlantic under the auspices of trade, the Dutch West India Company wasted no time doing just that, plundering forts in the Caribbean and Brazil that they turned into military outposts and plantations, and seizing Portuguese strongholds in Africa that stimulated their engagement in the slave trade. The colony they founded in what is now New York was short-lived, though digitized records in the New York State Archives testify to the colony’s rich and colorful history and challenge Anglo-centric narratives of seventeenth-century America.

Seventeenth-century Dutch expansion fueled advances in science and philosophy that were instrumental in defining the broader intellectual world. The prosperity, dynamism, and comparative tolerance of the Dutch Golden Age attracted thinkers from throughout Europe. Celebrated Flemish mathematician, Simon Stevin, whose family had fled the Catholic Spanish Low Countries, introduced the mainstream use of fractions, along with music theory and military engineering and design. While a certain Italian astronomer usually gets credit for the invention of the telescope, Dutch lens maker Hans Lippershey applied for the first patent in The Hague in 1608. On the other end of the spectrum, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek developed the microscope, documenting observable microorganisms in letters to the Royal Society in London. Law prodigy Hugo Grotius wrote Inleidinge tot de Hollandse Rechtsgeleerdheid, or Introduction to the Jurisprudence of Holland in 1631, ushering in a new era of practical standards for the application of natural law. Astronomer and physicist Christiaan Huygens studied wave theory, identified the rings of Saturn, created the pendulum clock, and wrote mathematical treatises. As one of the movers and shakers of the Scientific Revolution, Huygens was a member of seventeenth-century Dutch intellectual circles that included French philosopher and ex-pat René Descartes. Letters written between Grotius, Van Leeuwenhoek, Huygens, Descartes, and other scholars have been transcribed and made available online through the collaborative project, Circulation of Knowledge and Learned Practices of the 17th-Century Dutch Republic, at http://ckcc.huygens.knaw.nl/. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall.

Learning to read seventeenth-century Dutch also facilitates access to Dutch religious history that has bled into several disciplines. Distinctively grounded in the Eighty Years’ War, the tug-of-war between Spain and the Dutch Republic over the Catholic South and the Protestant North ended with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, but not before internal conflicts inspired the Synod of Dort that anchored Calvanist Protestantism in Europe. On the advice of the Synod to make the bible accessible to everyone, the Statenbijbel (States Bible) was commissioned and translated from original manuscripts in 1637 as the first authoritative Dutch-language Protestant book. Jews fleeing Spanish and Portuguese persecution also played an active role in seventeenth-century Dutch history. Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza, the son of Portuguese Jews, was both influential and controversial for his outspoken views on religion, eventually excommunicated from the synagogue in Amsterdam. Even the Pilgrims settled temporarily in the relatively tolerant Dutch Republic between leaving England in 1608 and establishing the Plymouth colony. Dutch records of their twelve-year stay in Leiden are kept at the Pilgrim Museum there.

Perhaps the most visible representation of the seventeenth-century Dutch is the art of the Dutch Golden Age. Artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, and Frans Hals reflect the era’s prosperity and expansion of theoretical boundaries as timeless foundations of the art world. Works like Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, set in the Anatomy Theater of Leiden University, graphically displays the scientific curiosity of the era, while Vermeer’s Officer and a Laughing Girl suggests the application of mathematics and science, more subtly, in its geometric and optical effects. The map in Vermeer’s painting is a strikingly accurate rendition of the original, published by renowned seventeenth-century Dutch mapmaker Willem Janszoon Blaeu. True to Vermeer’s representation, such maps graced the walls of many affluent seventeenth-century Dutch households, their popularity spurred by fascination with the New World, superior Dutch mapmaking, and the flourishing print industry in Amsterdam. While, in the words of Art Historian Mathilde Andrews, “you can’t write a painting,” there are primary sources aplenty for researchers delving into the Dutch Masters and their work. More than 500 documents related to Rembrandt are housed at the Municipal Archives in Amsterdam, including an inventory of goods in his home at the time of his death.

Prophetically, the words, “If you build it they will come,” floated through my mind like I was Kevin Costner in Field of Dreams. The enthusiastic response to the blog’s launch confirmed what I already suspected—that researchers are interested in accessing the primary sources of the seventeenth-century Dutch, if they can find help reading them. Whether your field is Early Modern Europe, Early America, Colonial History, Atlantic History, African Studies, Asian Studies, Religion, History of Science, Philosophy, or Art History—the list goes on—the Dutch were there, for better or for worse. The rich and prolific history the seventeenth-century Dutch produced crosses geographic borders and resonates deeply into surrounding temporal spaces, but much of it lies understudied in archives around the world. It is accessible with a basic foundation in Dutch or German, and now, with online support for learning. Twenty-three million people speak Dutch today as their primary language. If you feel you are somehow missing out, or find you are suffering from a vague, unsettled feeling that something is lacking from your scholarly endeavors, perhaps it would help if you looked into what the Dutch have been talking about all this time. It just might be exactly what you have been looking for.

Julie van den Hout is a graduate student in History at San Francisco State University focused on the seventeenth-century Dutch, Early America, and the Atlantic. She is currently working on a digital humanities project, through a grant from the New Netherland Institute, on ships that made port in New Netherland. She is the author of Adriaen van der Donck, A Dutch Rebel in Seventeenth-Century America, published April, 2018 from The State University of New York Press. She can be reached at jvandenhout@mail.sfsu.edu.

Featured Image: Officer and Laughing Girl, Johannes Vermeer, ca. 1657. Wikimedia.

October 3, 2018 at 7:58 am

excellent post. Fits in very well with the Teaching Company Course— Dutch Masters: The Age of Rembrandt. Professor William Kloss, M.A. Independent Art Historian— which I am now watching. Thank-you.

December 17, 2018 at 7:14 pm

A very good essay!