by guest contributor Richard Calis (April 2015)

For those who care to look closely enough, the world of early modern philology has many treats in store. Contrary to its reputation as nit-picking, dull scholarship, philology is in fact a discipline full of love, strife, passion and emotion. One such passionate and dedicated, yet now sadly unknown practitioner was Pieter Fontein (1708-1788). A student of the renowned Dutch philologist Tiberius Hemsterhuis in Leiden, Fontein became a teacher at the Mennonite Church in Amsterdam in 1739 and would remain so until his death some fifty years later. Over his career, Fontein amassed an impressive collection of Latin and Greek classics, all of which he bequeathed to his church, except for a small group of related books on the Greek philosopher Theophrastus. It is this collection of forty-three Theophrastiana (currently in the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam) that brings back to life the philological achievements of a scholar who never made it into the annals of classical philology.

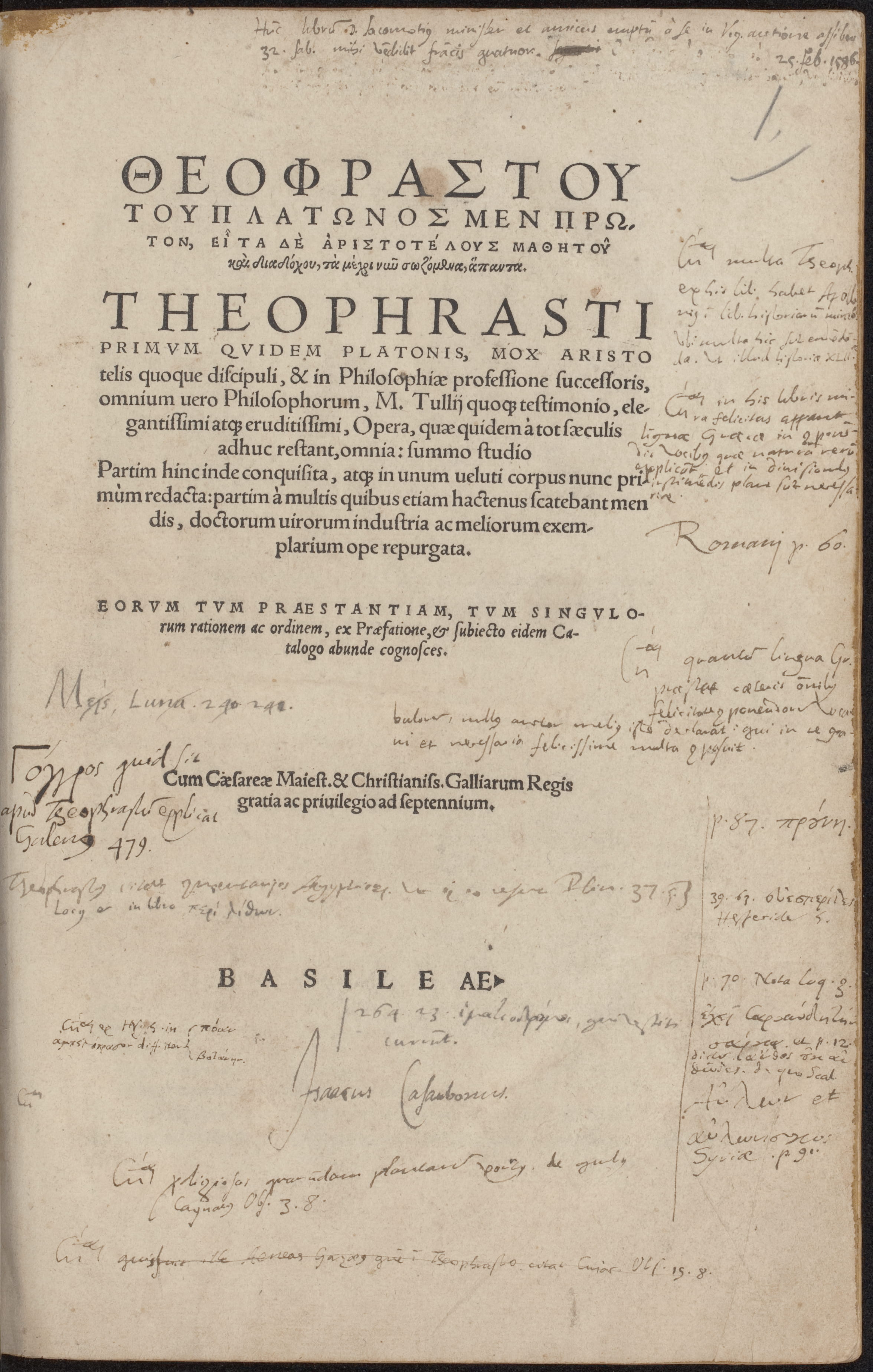

Casaubon’s annotated copy of Theophrastus. By permission of the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. Shelf mark: OTM: Hs VII D17.

It is still unclear when exactly Fontein amassed his books, but our story begins in 1754, when he was spending his days reading a rather special book from the collection of the then-famous botanist and Professor of Anatomy Willem Röell (1700-1775). The book that Fontein found so absorbing was a 1542 edition of Theophrastus’ Opera Omnia, printed at the famous Froben press in Basel. Moreover, the book was nothing less than a working copy of that great Theophrastus scholar Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614), who, over a century earlier, had adorned its pages with numerous notes and annotations.

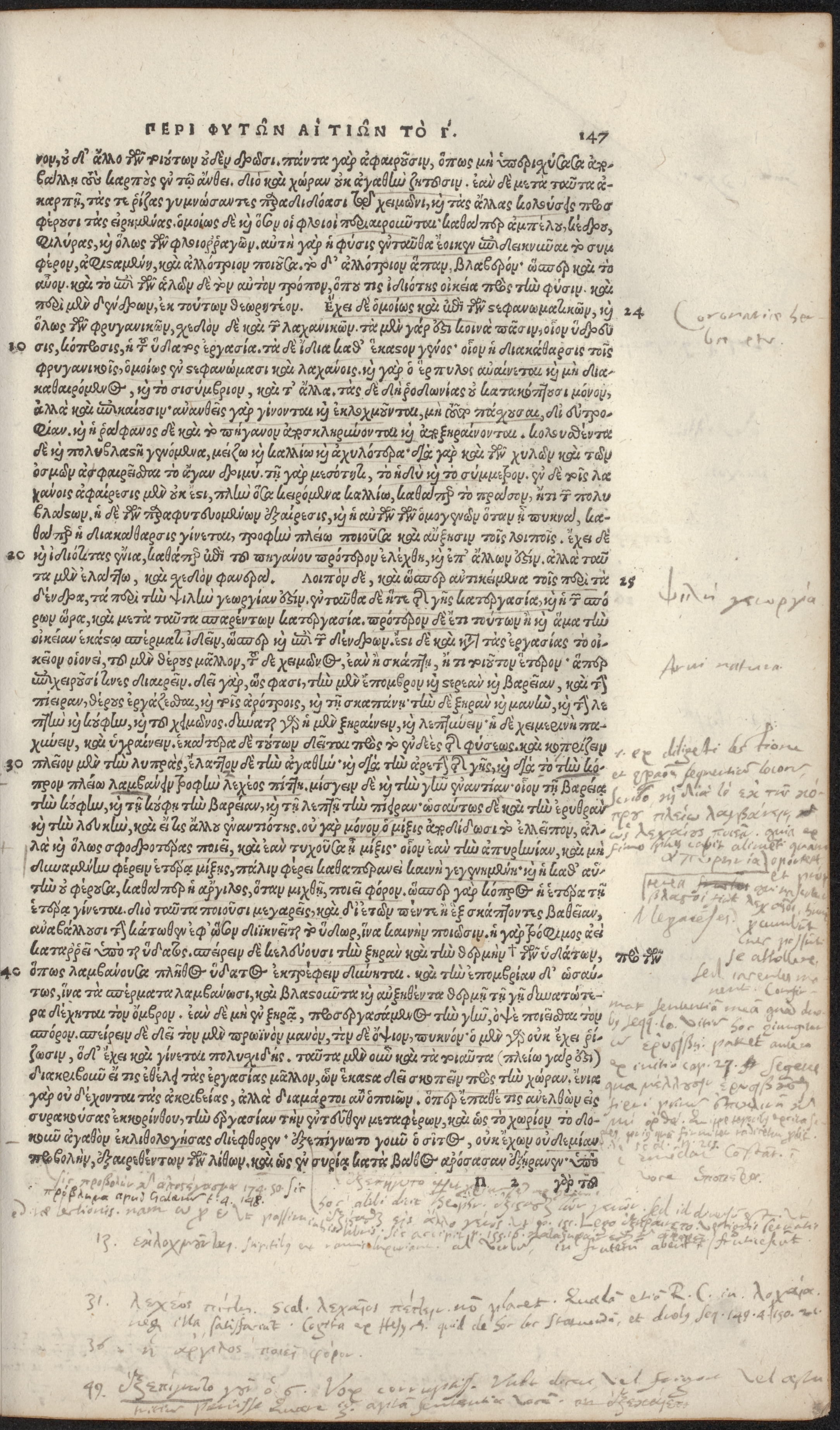

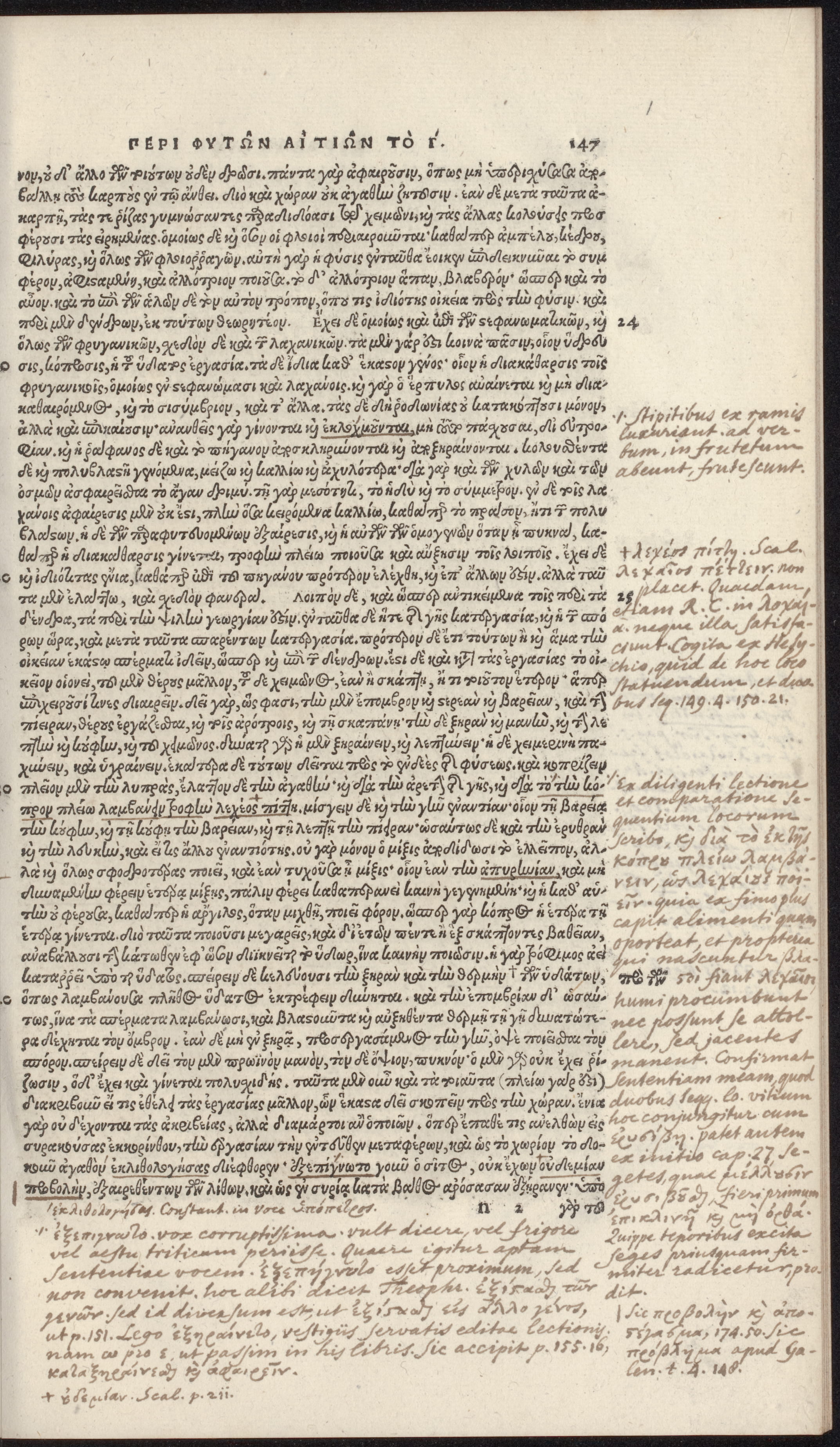

In 1591, Casaubon had published his own edition of Theophrastus’ Characteres, a lively set of character sketches known for its problematic text and manuscript transmission yet also the philosopher’s most popular work. Ever since, Casaubon was known to the world of scholarship as the single most important authority on Theophrastus, a reputation that was not lost on Fontein. In fact, the primary reason that Fontein took an interest in Röell’s book was because of Casaubon’s marginal notes. This, at least, is suggested by the way in which Fontein treated them: when he went to examine the book, Fontein bought and brought with him his own clean copy of the same 1541 edition —no mean feat more than two centuries after its publication— and herein copied nearly every single annotation that Casaubon had left in his book. For pages on end, Fontein faithfully transcribed Casaubon’s notes in his own beautifully regular eighteenth-century hand.

Casaubon’s marginal notes. By permission of the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. Shelf mark: OTM: Hs VII D17.

Fontein’s transcription of Casaubon’s annotations. By permission of the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. Shelf mark: OTM: Hs VII D19.

We may pause for a moment to appreciate the great intimacy of this —to my knowledge— unique practice of relocating marginalia from an annotated copy to a pristine one. To Fontein, these were not only notes explicating a text, but also the material evidence of the reading and annotating practice of one of his greatest predecessors. We know of scholars who organized their information in commonplace books but buying a two hundred year old edition to copy notes in was not everyday practice; not even for Fontein, whose book collection does not seem to include any other such inscribed copies. It will come as little surprise then that Fontein would even go on to buy Röell’s book in 1767, when the latter found himself in rough financial waters. After all, a transcription of Casaubon’s annotations was surely no replacement for the original.

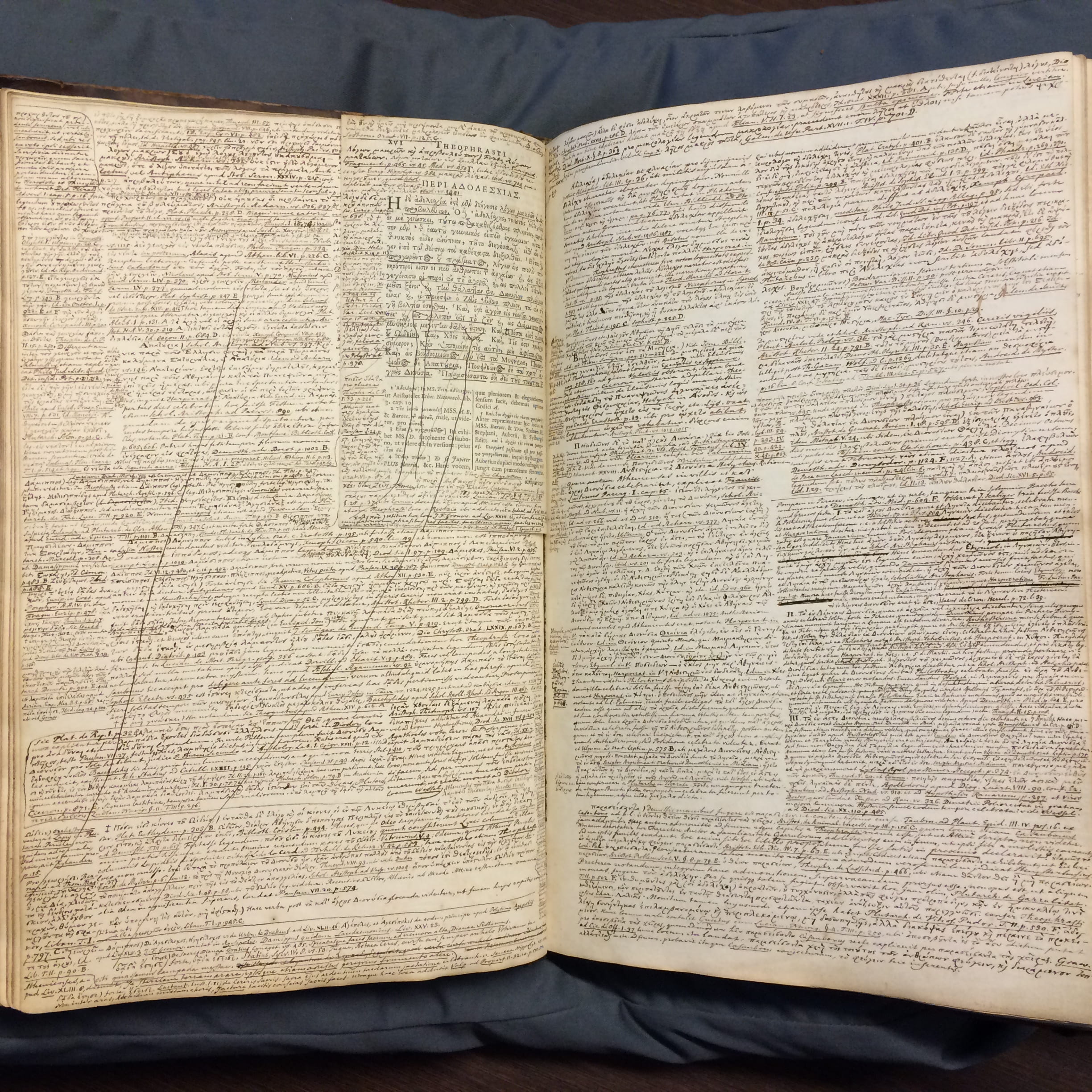

By then, Fontein had steadily collected more and more Theophrastus editions dating from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Some of them were densely annotated. This collecting spree was undoubtedly aimed at gathering every bit of information on Theophrastus that was available. As another copy from his library attests, Fontein was concurrently working on his own edition of the Characteres, Originally, he drafted his material in a small, handy octavo reprint of Casaubon’s edition, published in Cambridge in 1712. Yet today it can hardly be recognized as such: the edition is now completely interleaved with huge folio-sized pages, all of them awash with Fontein’s corrections, notes and interpretations. From these ‘additions’, one can observe how he continuously reworked the text. Fontein crossed out sentences, rewrote entire paragraphs, emended or explicated words, and crammed new notes in the margins of the margins. There are at least four drafted introductions to the work and its author, some prolegomena and countless comments and notes on the Greek; horror vacui takes on a whole new meaning.

Fontein’s working notes on Theophrastus. By permission of the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. Shelf mark: OTM Hs. XVI A5.

Sadly, the project came to nothing, as Fontein died before its completion. But even in his final days, the philologist’s passion for the project burned steadily. In his will —made in 1769, specified in 1775, and now in the Amsterdam City Archives— Fontein gifted all his books to the Mennonite Church with the sole exception of the Theophrastiana, which he wanted to keep to himself. We can almost see how the elderly Fontein with only a handful of necessary books unceasingly fine-tuned his views on a notoriously elusive text, while continuously adding new material to his already massive commentary. Again and again he kept revising, never gave up, and continually worked on a more accurate edition, with Theophrastus on his mind and his cherished Casaubon on his desk. What a character he was.

Richard Calis is a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate in history at Princeton University. He has worked for Annotated Books Online (ABO)—which provides online access to three of Fontein’s books— and is predominantly interested in books and their readers, antiquarianism, and the history of scholarship. His dissertation offers a microhistory of Martin Crusius (1526-1607) and his ethnographic interests in the Ottoman Greek world.

Leave a Reply