By Editor Derek Kane O’Leary

The monumental, bronze face of Leif Erikson gazes westward from Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue toward the nearby Charles River, which wends by Cambridge toward its modest source in Hopkinton. Since 1887, Leif has towered there as a pioneer in contrapposto, powerful, jaunty, and lightly arrayed in a nineteenth-century rendition of Medieval chic. Leif’s red sandstone pedestal rests on the prow of a diminutive knorr, the infamous Norse vessel of commerce and warmaking. In Old Norse runes, “Leif the Lucky, son of Erik” is engraved on the block’s front. On its back, in English, “Leif the Discoverer, Son of Erik, who sailed from Iceland and landed on this continent, AD 1000.” On one side of the block, Leif in miniature holds the same pose atop the craggy shore of the New World, as his crew clambers behind him. We peer out with him upon the continent. As the late nineteenth century contemplated the eleventh, we contemplate both from the twenty-first.

Leif stands along the central axis of the entrancing neighborhood of Back Bay. Lined with manicured Victorian brownstone houses, shaded by its nineteenth-century elms, Back Bay is the version of Boston that travel guides feature and visitors seek out. A mile away, a row of monuments begins at the Boston Commons. An imposing equestrian statue of George Washington heads a series of significant Bostonians–Phillis Wheatley, William Lloyd Garrison, Samuel Eliot Morrison, among others. The monumental path ends with Argentinian President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and the Norseman, Leif.

Argentinian President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and the Norseman, Leif.

The statue owes much to Eben Norton Horsford, an outstanding nineteenth-century American chemist and Harvard professor, who in his last decades immersed himself in the history and archaeology of the area. With the considerable wealth generated from his chemical patents (including a reformulation of baking soda and lucrative Civil War contracts with the government), he commissioned, donated, and dedicated the statue of Leif with great fanfare in the nearly-completed Back Bay. At the dedication, elite Bostonians, Scandinavian societies, and eager lookers-on heard celebratory speeches at Fanueil Hall before proceeding across the city to the statue’s unveiling. With this, Horsford realized what a coterie of like-minded Bostonians had dreamed of over the preceding decade (a fine discussion of the creation, form, and reception of the statue, here).

But why should late nineteenth-century Brahmins be so compelled by an eleventh-century Norseman? Horsford was convinced that Leif had once alighted on Boston’s shores. In nearby Watertown (a short walk from Horsford’s own home), Leif would have planted the obscure settlement of Norumbega, whose location had been a mystery to scholars for centuries. Horsford wrote several books on local archaeology, which superimposed this story of Medieval European settlement onto Boston’s backyard. (As Patricia Jane Roylance insightfully explains, he reinterpreted a local landscape through the prism of Norse settlement, placing the mundane within this compelling past.) Leif became the metonymy for this settlement and the alternative hemispheric history that it furnished.

In the late nineteenth century, it was not a uniquely Boston or Brahmin phenomenon to announce the Norse as the first European settlers of North America, at some beachhead or another on the jagged coast between Newfoundland and New England. The American fascination with the antecolumbian Norse settlement emerged earlier, cultivated by the Dane Carl Christian Rafn, the guiding force of Denmark’s Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries. From the society’s founding in 1825, Rafn built a network of American readers in key literary and scientific institutions along the East Coast. He also undertook an extended publicity campaign about his research into the Norse settlement of North America.

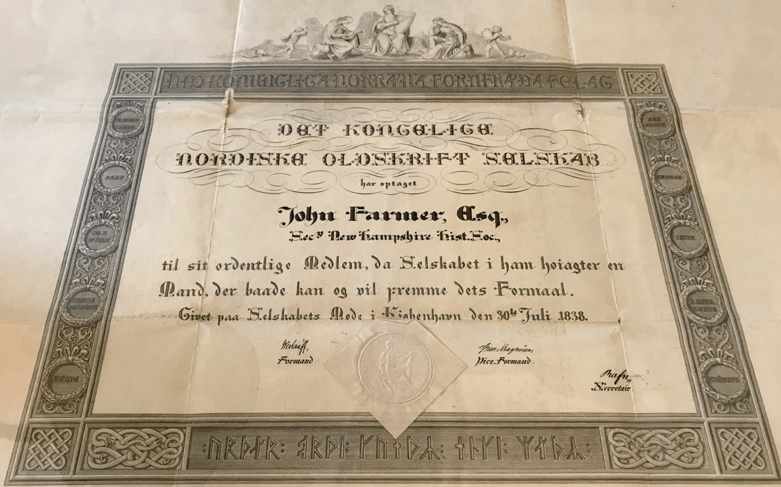

Carefully preserved, the large 1838 recognition of leading American genealogist John Farmer’s membership in Denmark’s Royal Nordic Society of Northern Antiquaries, led by Carl Christian Rafn. It represents the paper rituals that connected historians and antiquarians around the Atlantic, as well as the cachet that Rafn’s institution and its version of antecolumbian Norse settlement attained in the antebellum U.S. Over the years, Rafn was also inducted as corresponding member in many, including the American Antiquarian Society and the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

One of his many correspondents, New Hampshire historian-genealogist John Farmer received word from Rafn in 1828 via the Danish minister resident in the U.S. Farmer was the seminal American genealogist of the nineteenth century. His years of soliciting masses of dispersed biographical data from a network of eager, meticulous New Englanders coalesced into his 1829 Genealogical Register of the First Settlers of New England. Farmer was obsessed with situating his contemporaries vis-à-vis their puritan progenitors, “those who first landed on the bleak and inhospitable shores of New England” (iii). However, Rafn’s claim about a far older and non-English historical narrative resonated with him. “From a very early period of our history,” he responded to Rafn, “it has been the opinion of some of our learned men that America was known to Europeans long before it was discovered by Columbus…but materials for such a work being few at that time in our country, and there being but little intercourse between our learned men and the learned bodies in Europe, the work was necessarily small and imperfect.”

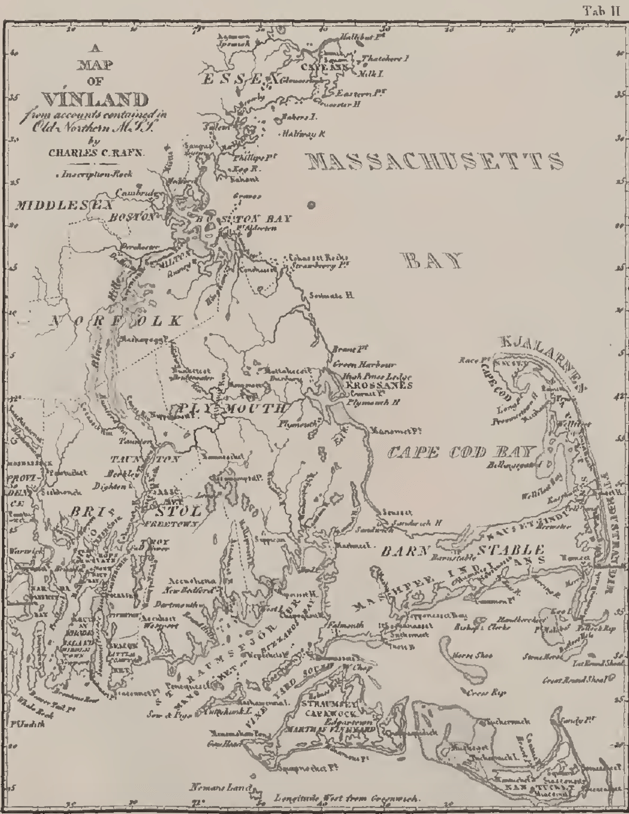

Carl Christian Rafn’s 1841 Supplement to his Antiquitates Americanae, which depicts Massachusetts and Rhode Island within the sweep of the Norse’s Vinland colony.

For Farmer and others, this moving Norse past could displace the narrative of American founding anchored in Columbus’ voyages and the depredations of Spanish colonialism. Through his correspondence and eventual publication of Antiquitates Americana in 1837, the Dane introduced Farmer and a range American history writers and readers to this counter-narrative of the hemisphere.

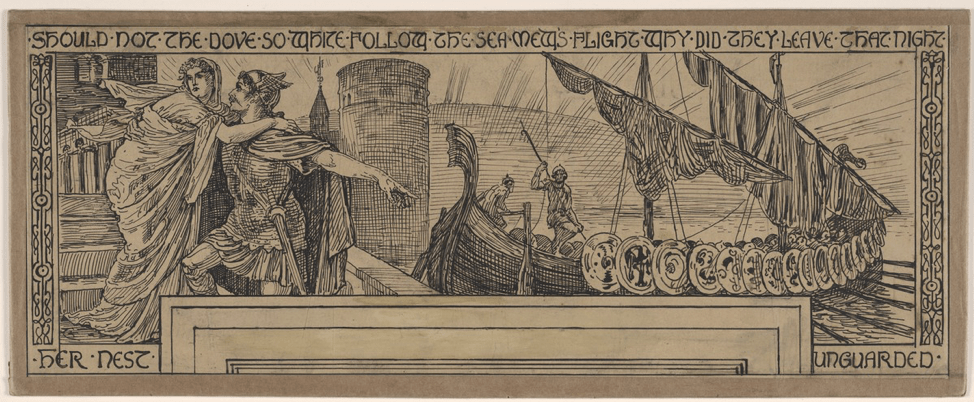

Walter Crane, “The Skeleton in Armour” (1883). “Four sketches, ink and graphite on board, for a six-panel mural frieze designed for Catherine Lorillard Wolfe as a room decoration for Vinland, her Scandinavian-style house at Newport, Rhode Island.” (Beinecke Rare Book and Manscript Library). Rafn projected the lost Norse colony of Vinland over the familiar landscape of New England, inspiring New Englanders to imagine a new history for themselves. In his 1841 poem “The Skeleton in Armor”, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow recast Newport Tower, a colonial windmill in Rhode Island, as a Medieval Norse edifice (center-left). Before it, an armor-clad skeleton previously unearthed in nearby Fall River, Massachusetts is reanimated as a medieval Norse settler. (For most contemporaries, the skeleton was clearly an indigenous American.)

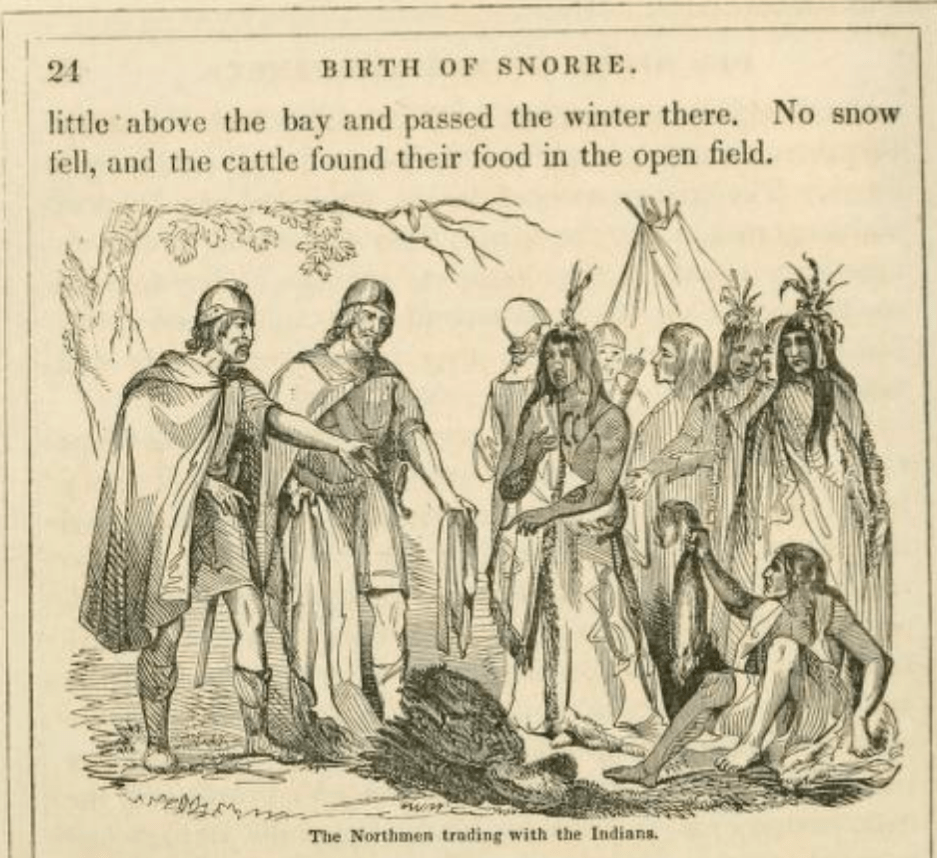

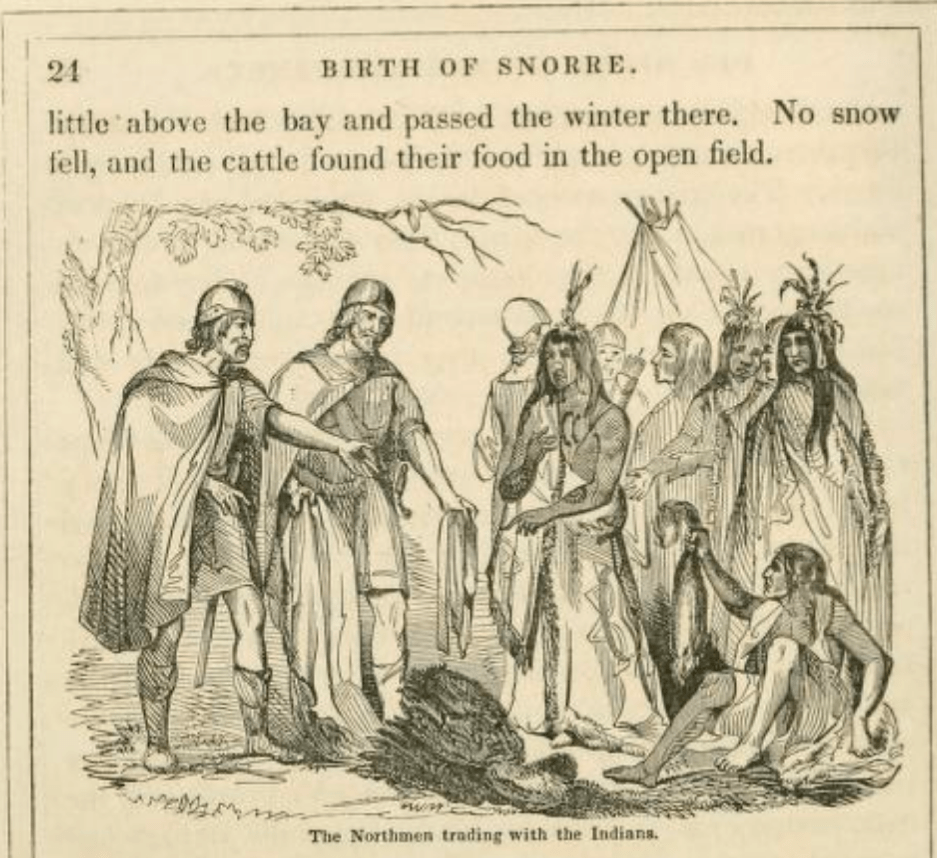

American children watched the Norse sail into their schoolbooks in the 1840s as the first European settlers of the continent, among other firsts (see figure 2). Into the 1850s, audiences pondered prolific lecturer Asahel Davis’s query: “it is not a laudable curiosity that leads one to ascertain what white men first trod regions in which the modest wild flower waster its sweetness on the desert air?” Emanuel Leutze, famed German-American artist “Washington’s Crossing” (1851), “Departure of Columbus from Palos (1855), and “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way” (1860), preceded those dramatic passages of American history with another: “The Landing of the Northmen” in 1845 (since disappeared, it seems). After the Civil War, historians along New England’s coast disputed the location of Norumbega. Yet in all such expressions of national history, Leif’s endeavors along the early eleventh-century New England coast could predate Columbus on the first page of national history: the first European born on the continent, the first Christian mission to the natives, the first commercial exchange and productive use of the land–all pivotal moments in the narrative of seventeenth-century puritan settlement, too.

In his 1844 Pictorial History of the United States, secondary school educator John Front positioned Norsemen in tableaux paradigmatic of the seventeenth-century Puritan colonies on those very shores.

All agreed that the Norse settlement of America was fleeting, leaving no human lineage on the continent. The New England settlers documented by Farmer remained the genealogical touchstones that many Americans turned to. Nonetheless, American historians, authors, artists, and audiences could conscript the Norse into their national story. Through the second half of the century, the early Christianity and seemingly free government of the Norse were increasingly cast as historical antecedents to the founding of the Anglo-Saxon nation, which for nineteenth-century readers seemed destined to steward world history forward.

At the 1887 celebration of Leif’s statue, Harper’s Weekly mused that in his gaze gleamed the

prophetic of the future, of the later republic founded by kinsmen of the Icelanders, who for love of liberty dared the harshness of the bleak New England, as the Norsemen before them had braved the rigors of that uninhabited Iceland, with its geysers and jokuls, in the ninth century, to establish their republic of law and letters. The knit brow and noble bearing of Leif tell not only of the firm resolve and daring of the explorer, but also that he was a worthy forerunner of the Pilgrims.

Here, the Norse are placed in the Pilgrim mold, and the Pilgrims are themselves depicted as intrepid, freedom-seeking individuals (as opposed to long-standing critiques of their religious extremism). Horsford argued as much himself, lauding that Leif’s “ancestry were of the early pilgrims or Puritans who, to escape oppression, emigrated 50,000 of them in sixty years from Norway to Iceland, just as the early Pilgrims came to Plymouth” (quoted in this fascinating discussion of the broader appeal of Medieval history and aesthetics in the second half of the century, by Robin Fleming). If this late nineteenth-century depiction of New England’s settler generation could be used to rarefy the image of rapacious Norsemen, the revision of Norse identity could also affirm the values and identity espoused by Americans claiming descent from it. More specifically, as Fleming argues, it linked a socially, culturally, and racially-select cohort of the living to an imagined Teutonic past, conceived as the Old World origin of the exceptional institutions and ideals brought to fruition in the U.S.

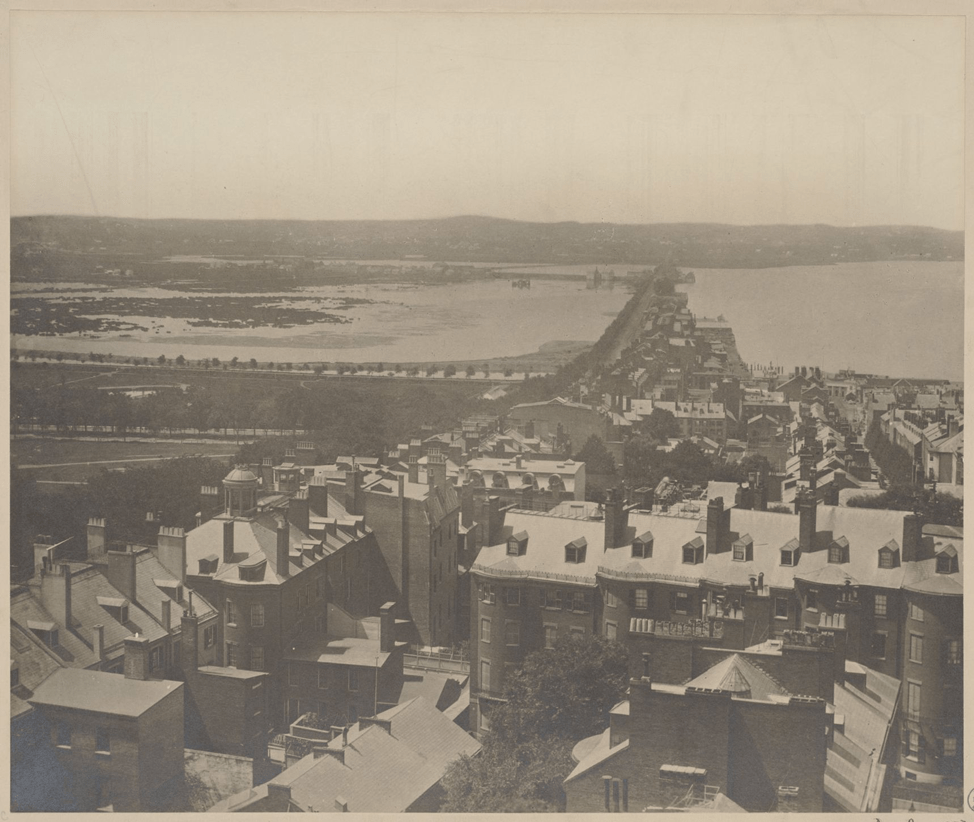

View of Back Bay, to the upper left, from the dome of the Massachusetts State House in 1857.

Alongside this longer transatlantic intellectual tradition and historical revisionism, three decades of colossal land reclamation had made Leif’s 1887 placement in Back Bay possible. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Boston’s population strained both the capacity of its scant landmass and, with the influx of impoverished Irish immigrants, the sensibilities of the native-born Protestants population. In Back Bay, city planners and proponents envisioned an orderly suburb that would staunch the migration of affluent Protestant Bostonians beyond the Charles River and craft a physically and morally pristine space within Boston. In its special planning committee’s words, the neighborhood would “secure upon the premises a healthy and thrifty population and business, and by inherent and permanent causes, forever to prevent this territory from becoming the abode of filth and disease” (In Stephen Puleo, City So Grand : The Rise of an American Metropolis, Boston, 1850-1900, Beacon Press, 2010, 87-88). Stately, rectilinear streets were laid over six hundred acres of formerly fetid, briny tidal basin to house the city’s Anglo-Protestant elite. Much of the labor was performed by the very immigrants Back Bay was supposed to be purified of. As Back Bay neared completion and Leif’s statue appeared in 1887, a new influx of diverse European immigrants to the region stoked old racial and class anxieties. Many of these were Italians, who could claim some lineage with Columbus as the quadricentennial of his landing in Hispaniola approached. In contrast to them, Scandinavian immigrants appeared the “fairest among the so-called white races”, having “been trained to industry, frugality and manly self-reliance by the free institutions and the scant resources of their native lands” (Professor H.H. Boyeson, “The Scandinavian in the United States,” North American Review, Nov., 1892).

When Horsford convened the Bostonian elite to sanctify Leif’s statue and the historical arc it embodied, he aligned this rendition of the nation’s past with the geographic reimagination of ethnicity and class within the city. In Leif, a version of the nation’s past coincided with the meaning embedded in that contemporary urban geography.

Back Bay disentangled the local Anglo-American and Protestant elite from a city transformed by the influx of struggling Irish and, by late century, Italian and Eastern European immigrants. And the statue consecrated a historical arc from Leif the New England settler, through the seventeenth-century colonists, and toward the individuals embedded in that very neighborhood.

Many thanks to Brendan Mackie for his thoughtful editing of this.

Leave a Reply