by Madeline McMahon (November 2015)

After midday on August 14, 1483, the Dominican friar Felix Fabri and his fellow pilgrims to Jerusalem began to prepare for their celebration of the feast of the assumption of Mary. They constructed a small kind of tent around the altar in the very “place from whence the blessed Virgin was carried off” to heaven after her death and created “a beauteous holy grove,” adorned with “leafy boughs of olive and palm trees, strewed with grass and flowers.” In the evening, incense intermingled with the scent of the branches, and the pilgrims sang “Et ibo mihi ad montem myrrhae.” After the service, a group of Eastern Christians used the same space, although Fabri was unimpressed with their hymns: “they seem to wail rather than to sing.” Nevertheless, the liturgical calendar dictated when both Fabri’s Western Christian companions and their Eastern Christian neighbors celebrated this particular feast. But because they were in Jerusalem, the actual place associated with the Virgin’s death also played a central role in their liturgical celebrations: they circled her sepulchre in a procession and sat vigil around it throughout the eve of her feast (Fabri, Evagatorium, trans. Stewart, 7.193-4).

Later in his journey, Fabri returned to where “Mary departed from this world,” but described it very differently. On a walking tour, Fabri’s group “came at no great distance to another place enclosed with a higher dry stone wall, wherein tradition says that the house of the blessed Virgin stood, wherein she lived a domestic life for fourteen years” (8.328). Rather than singing solemnly and adorning the place with branches, Fabri elaborated on the tradition surrounding the Virgin’s life after the death of Jesus. In fact, his understanding of that tradition is perhaps surprisingly inclusive (although mediated and confirmed by a Christian source, Nicholas de Cusa): “We are told in the Alcoran of Mohamet that she only survived five years [‘after our Lord’s ascension’], and that her years in all were fifty-three, as is said also by Nicholas de Cusa, Book II, chapter xv” (ibid.). The physical location (or locus) of Mary’s house led Fabri to cite two passages (loci) in order to solve—or at least state possible answers to—a chronological conundrum. Two meanings of the Latin word locus, textual passage and physical place, overlapped.

As the center of the liturgical celebration, Mary’s grave might be seen as a lieu de mémoire, a site for formally memorializing a long-ago and otherwise inaccessible event (Nora, ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire’, Representations, 26 (1989), 7-24). But in Fabri’s walking tour, Mary’s house functioned as a kind of commonplace heading on the topic of her life after Christ and death. By analogy, the landscape could become a commonplace book, with each new holy site a potential topical heading to organize various related texts and relevant oral knowledge. Text could be inscribed on the terrain.

A book inflecting the way space was approached was nothing new, of course—that was the essential premise for pilgrimage itself. Petrarch populated his 1358 Itinerarium to the holy land with famous literary figures. He celebrated the cities on route to Jerusalem for being where Vergil wrote the Georgics, or Pliny the Elder died in volcanic ash (trans. Cachey, 10.3). And he assumed that his reader was comparing his itinerary with the words of famous authors ringing in their ears: “It should not surprise you that Virgil in the third book of the divine poem [the Aeneid] apparently placed [Scylla and Charybdis] otherwise. He was describing in fact the voyage of one who was arriving while I the voyage of one who is departing” (12.1). He also expected them to see “everything through the Gospel, which is fixed in your mind as you look” (16.4). But the reader’s familiarity with scripture often meant Petrarch felt he could pass over enumerations of minor holy sites and instead recount classical texts and histories. In contrast to Fabri’s later narrative, Petrarch’s imagined itinerary did not elicit the same references to specific texts, though he referred readers to Josephus for further information on a historical point (16.6). His guide to the holy land was meant to help his reader appreciate the landscape. The itinerary itself only loosely organized the texts that Petrarch alluded to reference to it.

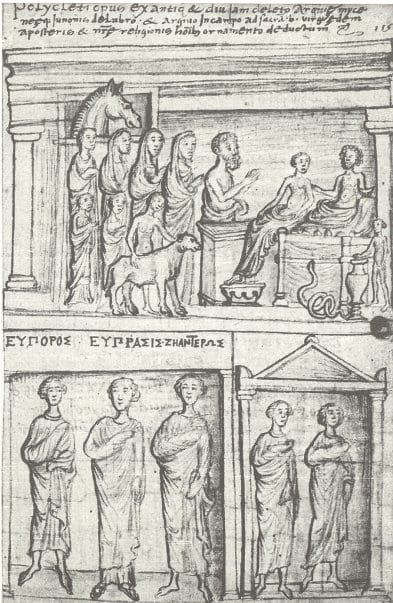

Cyriac of Ancona’s drawings of stone carvings on the Church of the Dormition of the Virgin in Agia Triada, Greece (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Cod. Trotti 373, f. 115r, nauplion.net)

Sometimes, though, the landscape could provide textual loci of its own. Cyriac of Ancona (1391 – 1452) traveled for mercantile business from a young age in the Mediterranean and was struck by the remains of classical and (to a lesser extent) Christian antiquity. He wrote six travel diaries, describing how his friends and hosts in Frankish towns and Venetian colonies guided him through fields to inspect “remnants” (reliquiae or monumenta) of antiquity, including ancient temples, floor mosaics, and hundreds of inscriptions (Diary V, trans. Bodnar, II.307 – 9). He believed, as his lifelong friend Francesco Scalamonti wrote, that “the stones themselves afforded to modern spectators much more trustworthy information about their splendid history than was to be found in books” (Scalamonti, Life, trans. Mitchell, Bodnar, and Foss, I.48 – 9).

Nonetheless, Cyriac frequently made use of texts to make sense of objects in the landscape. He identified the iconography of the Parthenon—then dedicated to the Virgin Mary— “from the testimony of Aristotle’s words to King Alexander” (quoted in Brown, Venice and Antiquity, 84). The landscape induced both Fabri and Cyriac to turn to texts, but Cyriac was more concerned with the material buildings and remains than Fabri, who used pilgrimage sites in his account to recount memories or textual loci. Texts made the landscape interesting to Petrarch, but both fifteenth-century travellers toggled back and forth between physical and textual loci to make them speak to each other. Cyriac even replicated the loci in the landscape for his friends, sending drawings and transcriptions of monuments across the Mediterranean. Most of his own manuscripts are now lost—as are many of the inscriptions he copied. But his writings circulated widely through scribal copies in his circle, preserving the landscape that so fascinated him in text.

Madeline McMahon is a 4th-year PhD candidate in history at Princeton University (and a former editor of JHI Blog). She studies the intellectual, religious, and cultural history of early modern Europe. Her dissertation examines episcopacy and scholarship in the Church of England and the Catholic Church in Italy after the Elizabethan Settlement and the Council of Trent, when the ancient institution of episcopacy was reimagined for a changed present.

Leave a Reply