by guest contributor Jonathon Catlin

The German historian Reinhart Koselleck (1923–2006) is best known as the founder of Begriffsgeschichte, or conceptual history, a historical methodology that culminated in the Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache, a massive eight-volume encyclopedia of fundamental historical concepts that Koselleck co-edited with Otto Brunner and Werner Conze. Toward the end of his life Koselleck moved away from his earlier project of conceptual history and directed his intellectual energies to issues of memory and iconography, as seen in his late collection of essays Zeitschichten (2000). Several essays from this volume, as well as some written after its publication, have been recently collected and translated into English as Sediments of Time: On Possible Histories (Stanford, 2018) with an introduction by Koselleck’s former student Stefan-Ludwig Hoffman (available free online).

Koselleck and conceptual history are having a veritable resurgence. One of the most interesting fruits born of this wave of interest is the three-part exhibition “Reinhart Koselleck und das Bild” (Reinhart Koselleck and the Image), which was displayed in Bielefeld, Germany, in spring and summer 2018. It was curated by Dr. Bettina Brandt and Dr. Britta Hochkirchen, two scholars affiliated with Bielefeld University, the history faculty of which Koselleck helped establish in the 1960s and where he taught until his retirement in 1988. Besides Koselleck’s conceptual history—documented in his archive and library at the Deutsches Literaturarchiv (DLA) in Marbach—he also took over ten thousand photographs, which are now housed separately at the Bildarchiv Foto Marburg and viewable online. Most of his photographs were part of two thematic projects, Politischer Totenkult (the political cult of the dead, with a focus on war memorials) and Politische Ikonographie/Ikonologie (political iconography and iconology, with a focus on equestrian monuments). These began as hobbies but matured into intellectual projects in their own right, with the former culminating in Koselleck’s 1994 co-edited volume Der politische Totenkult: Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne.

Selections of Koselleck’s photographs were displayed in three different locations around Bielefeld, each of which highlighted a different dimension of his work on iconography. Curators Brandt and Hochkirchen argue convincingly that the late Koselleck—and to some degree his earlier project of conceptual history as well—was deeply attuned to visual as well as linguistic semantics. They thus position Koselleck at the forefront of the recent “iconic turn” to aesthetics, political iconography, and metaphorology. Their curatorial work reveals that conceptual history’s traditionally logocentric tools of etymology, philology, hermeneutics, and historical semantics only achieve their true interpretive power when combined with the study of closely related icons, symbols, and images.

The exhibit thus links Koselleck to the Blumenbergian turn of recent works of conceptual and intellectual history such as the volume The Scaffolding of Sovereignty: Global and Aesthetic Perspectives on the History of a Concept (Columbia, 2017), co-edited by Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, Stefanos Geroulanos, and Nicole Jerr, which opens up a number of new approaches for conceptual history. This work illustrates through diverse case studies that sovereignty is at once a concept that can be “filled up” with different meanings in different times and places, an image inextricably linked in political modernity to the iconography of the Hobbesian sovereign, and a Blumenbergian “absolute metaphor” of the visualization of the body politic in one sovereign. This turn toward linking conceptual history with aesthetics and political theology has helped put some final nails in the coffin of the fallacies of rationality and coherence that has long constrained the history of ideas to narrowly conceived “philosophical” subjects. The fact that Brandt and Hochkirchen—like Koselleck himself—have training in art history is evident in their attempt to open up conceptual history to new audiences, both within the academic world and for a public interested in the politics of memory and representation.

One political icon in particular preoccupied Koselleck for much of his life: the horse. The exhibit “Political Sensuality” (Politische Sinnlichkeit) displayed in Bielefeld’s Center for Interdisciplinary Research (ZiF) explored the way the modern political “space of experience” (Erfahrungsraum) engages all five senses and the body. It presents everything from his photographs of political symbols, such as statues of Karl Marx, to dozens of figures of horses from his personal collection—ranging from everyday products and advertisements emblazoned with horse iconography to collectable figurines Koselleck displayed on the bookshelves in his office, to the stuffed horse he took naps with in his old age.

The horse captivated Koselleck because it was employed by a wide range of modern political ideologies as a symbol of power and sovereignty. The equestrian statue was one of the fundamental symbols of political modernity and conveys the “space of experience” (Erfahrungsraum) of the Sattelzeit (1750-1850), the period of modern conceptual emergence at the center of Begriffsgeschichte. Koselleck characterized the horse as a privileged icon of the modern era and even wrote of an “equine age” (Pferdezeitalter).

As the horse lost its economic and military functions with the advent of industrial power, the automobile, and the tank, it was consigned to more trivial functions as a means of leisure and recreation. This was the meaning horses held for Koselleck in his own time, given his childhood passion for horseback riding. His impressive collection of figures captures this semantic shift, from commanding military figures to the playful carousel pony and rocking horse.

The curators argue that Koselleck was deeply attuned to the mediated quality of his images. He regularly took photographs of television programs, especially parades and ceremonies, that are marked by distortions, glare, and fuzziness, thus tangibly conveying their multi-mediated status.

Koselleck similarly kept poor quality photographs taken out of train windows that are often overcast by flash glare and others including reflections of his own face and hands. For the curators, these images seem to express a “double quality”: on the one hand, images seduce the eye and draw the viewer in, but on the other they create distance and distortion that keeps the viewer at a critical distance. This attention to visuality reflects Koselleck’s broader contention that history is always plural and contested: experiences, expectations, and interpretations pile up in layers and battle for significance and meaning. Koselleck’s photographs of statues of Karl Marx exemplify his attention to competing historical perspectives: a statue that from a distance looks imposing and commanding becomes an absurd caricature up close.

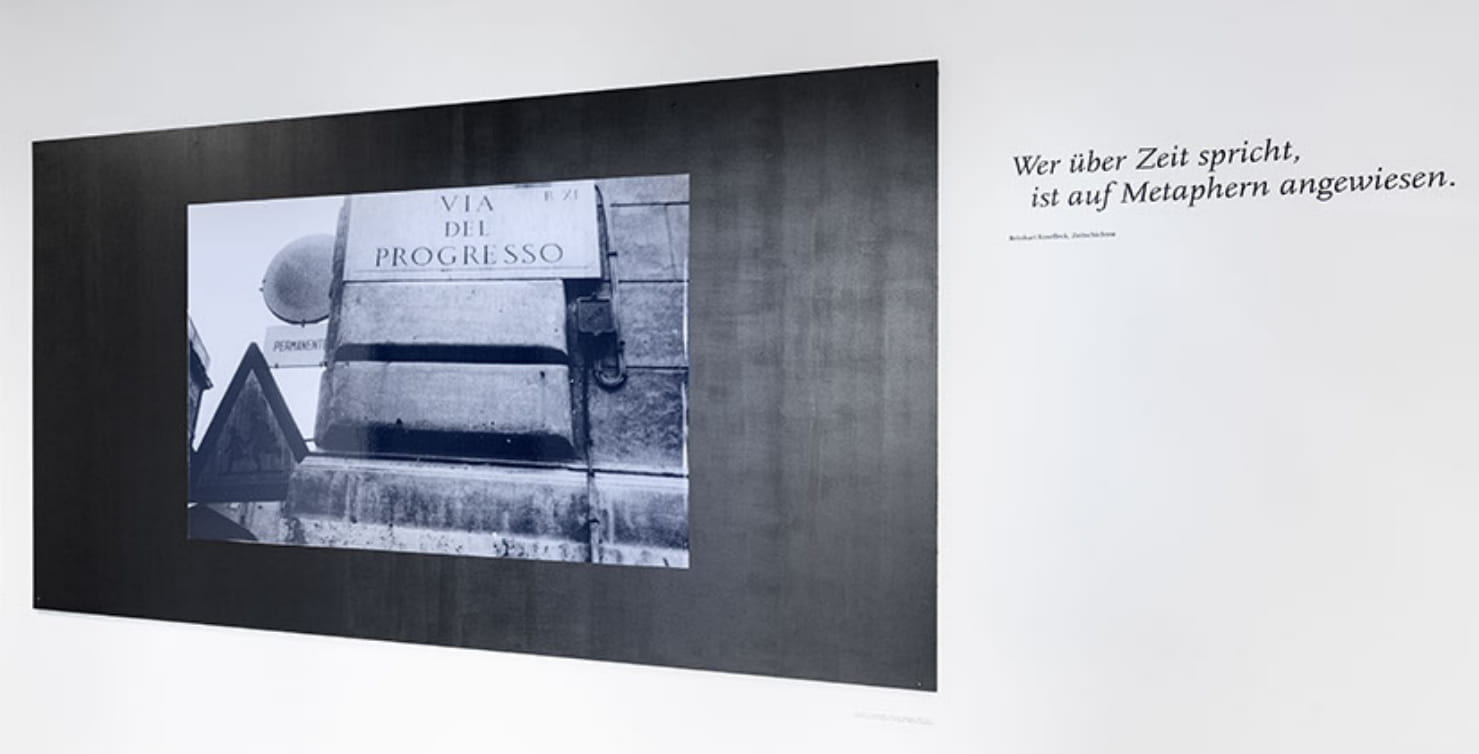

“Layers of Time” (Zeitschichten), which takes its name from Koselleck’s late collection of essays, is displayed in Bielefeld University’s History Faculty. It presents dozens of clusters of Koselleck’s photographs concerning historical objects, time, and experience, revealing his sharp eye for spotting layers of history, memory traces, anachronisms, uncanny juxtapositions of time, repetitions, and multiple modernities—what he, following Ernst Bloch, called “the simultaneity of the non-simultaneous” (die ‘Ungleichzeitigkeit’ des Gleichzeitigen). The visual aspect of the title layers or sediments of time recalls a quotation by Koselleck featured at the beginning of the exhibition: “Whoever speaks about time is dependent upon metaphors.”

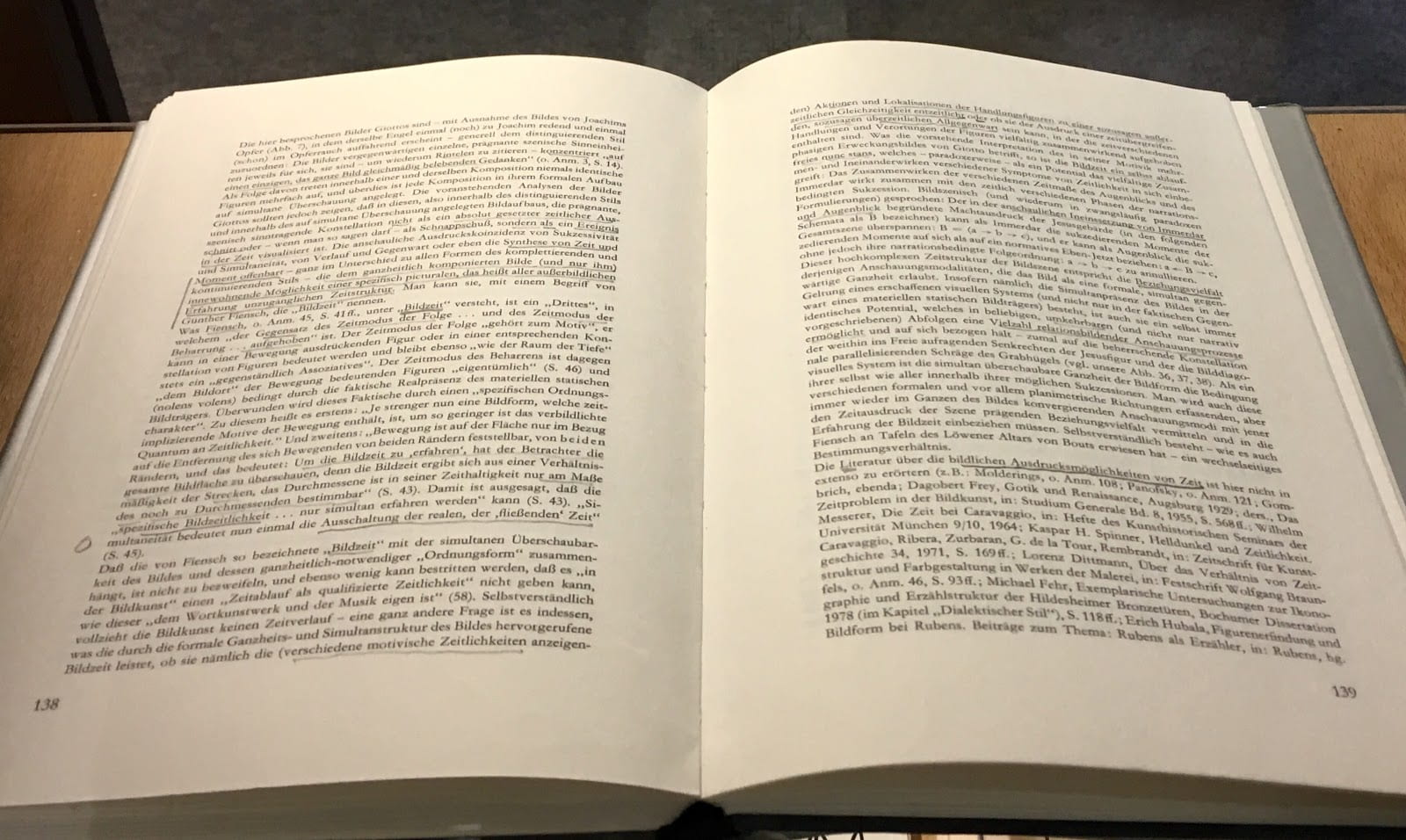

This exhibit also provides a bit of intellectual history behind Koselleck’s “image praxis.” He initially wanted to attend an art academy and become a caricaturist. He abandoned this plan in favor of history, but while studying in Heidelberg he continued to attend art history seminars. One of the few physical objects on display is Koselleck’s heavily underlined copy of Giotto – Arenafresken: Ikonographie, Ikonologie, Ikonik, a 1980 work of art criticism by his friend and colleague Max Imdahl (a fellow member of the group Poetics and Hermeneutics, which met around Germany from 1963–1994). Koselleck took particular interest in Imdahl’s notions of “Bildzeit” (image-time) and “Bildzeitlichkeit” (image-temporality), which theorize pictorial expressions of time—the layers of history sedimented within every image.

Koselleck’s underlined copy of Max Imdahl, Giotto – Arenafresken: Ikonographie, Ikonologie, Ikonik. Munich, 1980. Held at the Deutschesliteraturarchiv Marbach.

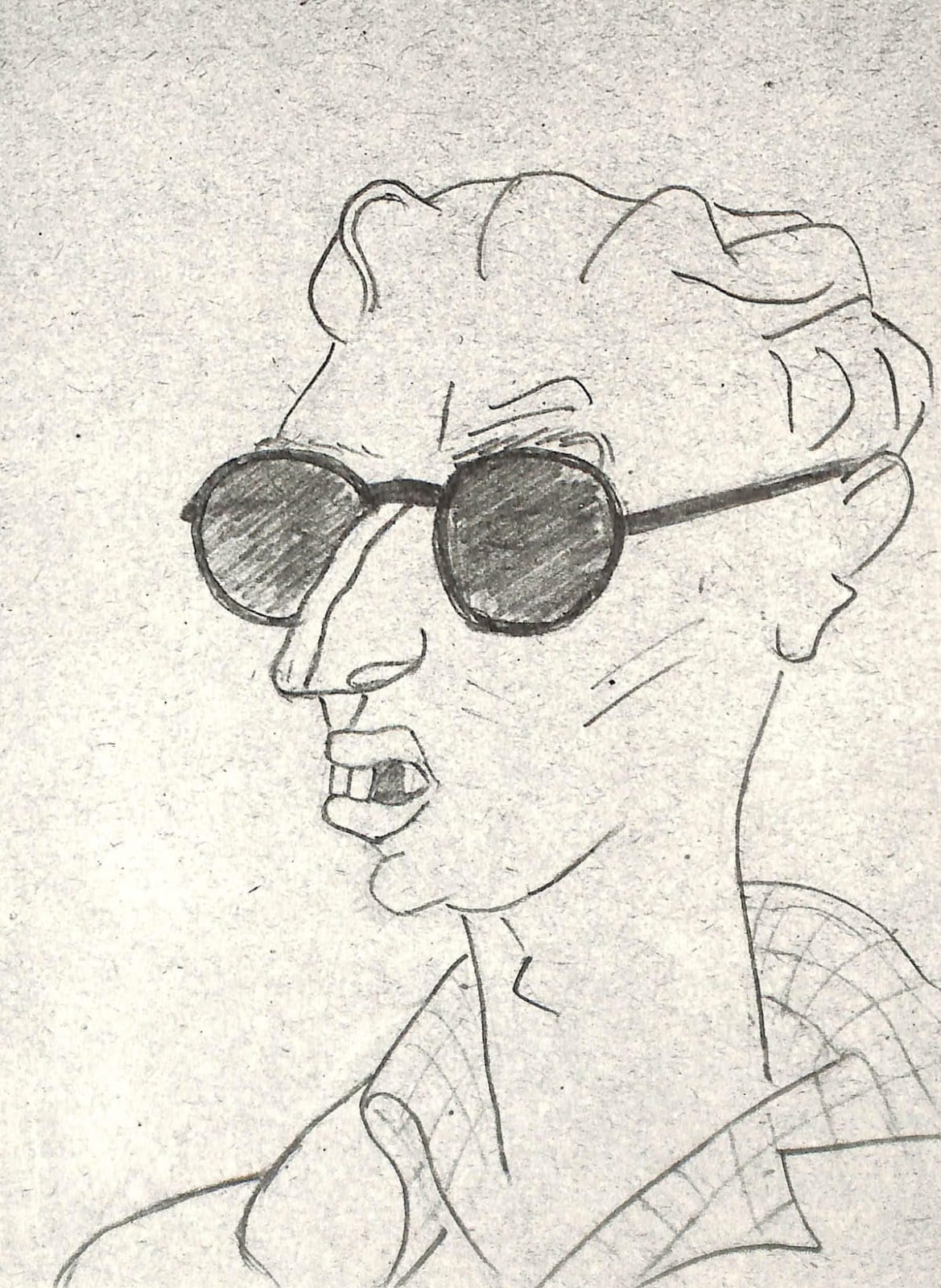

The exhibit also includes a small selection of caricatures from Koselleck’s own hand, which depict political figures such as Konrad Adenauer, Theodor Heuss, and Harry Truman, as well as his former professors Karl Jaspers, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Karl Löwith. In 1983, on the occasion of Koselleck’s sixtieth birthday, a volume of his drawings and caricatures was published as Vorbilder – Bilder, with a short introduction by Imdahl.

Koselleck’s caricatures, published in Vorbilder – Bilder, 1983. Top left: Konrad Adenauer in 1949 after his election as Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany; Top right: German Federal President Theodor Heuss on December 12, 1952, a few hours before his decision to rescind the judicial opinion of the Federal Constitutional Court against West German rearmament under pressure from CDU Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. The image is dedicated to Carl Schmitt, with whom Koselleck had a correspondence and whom he thanks in the preface to his first book, Critique and Crisis; Bottom right: “Oder? Oder?” comically depicts Polish leader Władysław Gomułka receiving Charles de Gaulle in 1967 to affirm the Oder-Neisse border between Germany and Poland.

Koselleck’s sketch of the British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, who taught Koselleck at a reeducation center at Göhrde castle in 1947.

Koselleck’s photographs often evoke temporal acceleration and the paradoxes of technological progress. In a single frame he frequently contrasts signs of progress and regression, utopia and catastrophe, forgetting and haunting. The most frequent image he sought to capture was the juxtaposition of a blurred modern high-speed train rushing past the stationary statue of a rider on horseback, representing the displacement of the horse by the train as the dominant mode of transit in Europe—yet also the persistence of equestrian iconography.

The final exhibit, “Memory Sluices” (Erinnerungsschleusen) was displayed at the Bielefelder Kunstverein and curated by its director, Thomas Thiel. It presents Koselleck’s foray into the politics of memory and the “cult of the dead”, which he argued was “one of the signatures” of political modernity in his 1983 essay “Sluices of Memory and Sediments of Experience.” As the European nation-state emerged as the center of modern life during the Sattelzeit, the Christian monopoly on the meaning of death through salvation and the afterlife gave way to the perpetuation of life through the political futurity of the nation. Koselleck’s work showed that this shift was evident in changing memorials for the dead. The French revolutionaries first sought to memorialize each individual fallen soldier regardless of rank, symbolizing the democratic principle of equality in sacrifice to the nation. Nations created a cult of those who died for them and erected magnificent monuments for their worship.

Monument to the Battle of the Nations, Leipzig, 1913 – Wikipedia.

World War One served as the high point of this practice of naming the dead regardless of their rank. In the battlefields of Flanders, the Somme, or Verdun, “no name could go missing” because “the equality of death becomes the symbol of the political unit of action” (Sediments of Time, pp. 218, 217). Koselleck connected such forms of memory back to structures of possible historical experience: “Wartime experiences could only be made and raised to the level of consciousness because they fitted into a grid of historically pregiven possibilities of experience…formed through language, ideology, political organization, generation, gender and family, class, and social stratum” (p. 213).

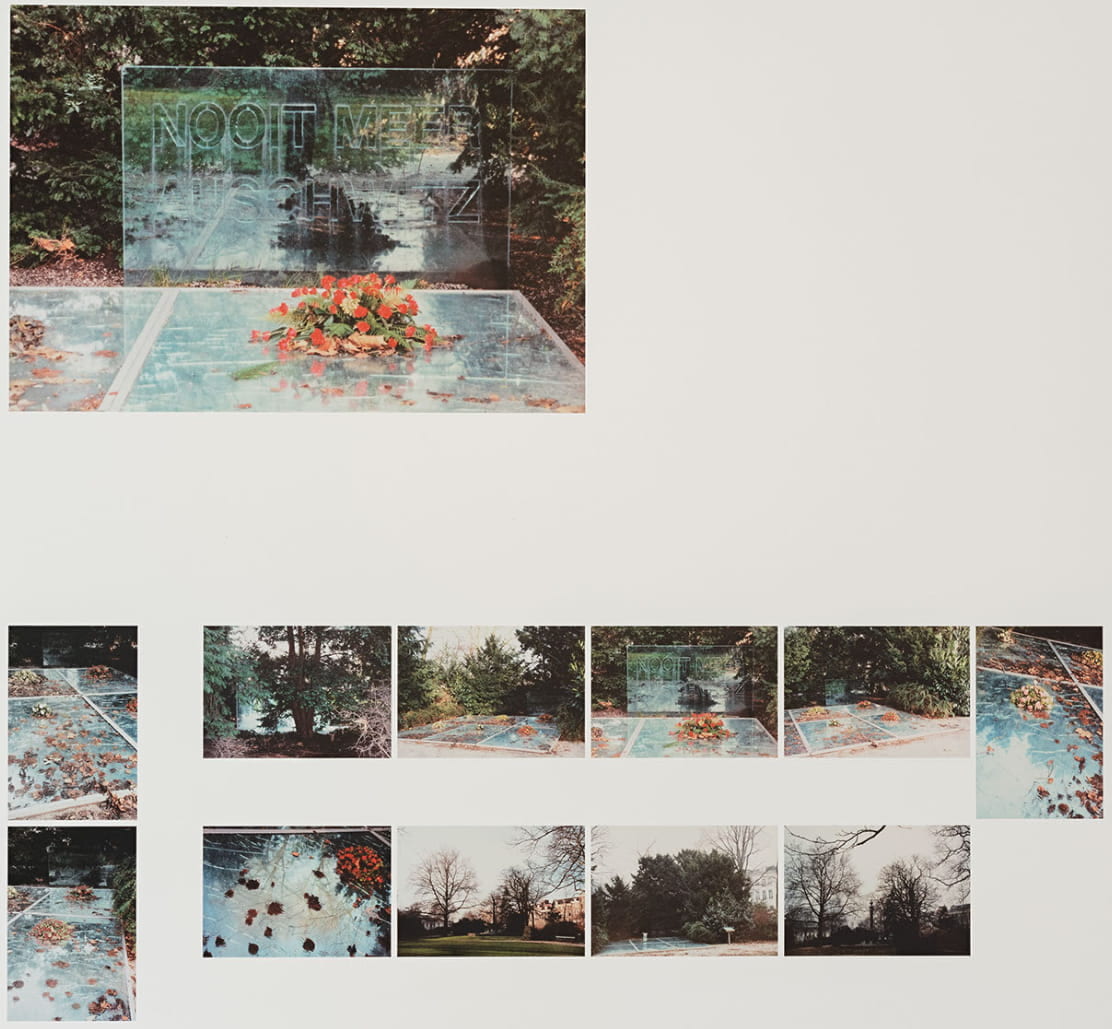

After World War One, however, and especially after World War Two, memorials ceased to name the individual dead because “sacrificial importance” could no longer be attributed to mass civilian death and genocide. In West German memorials for fallen soldiers and concentration camp victims, Koselleck wrote, “it becomes especially clear that death is no longer understood as an answer and instead only as a question, death no longer generates meaning, instead it calls out for meaning” (p. 218). In his 2002 essay “Forms and Traditions of Negative Memory,” Koselleck called this “negative finding” the “abysmalness” (Abgründigkeit) of remembering the National Socialist period: “Senselessness [Sinnlosigkeit] became an event. There is no attribution of meaning [Sinnstiftung] that could retroactively encompass or redeem all the crimes of the National Socialist Germans” (p. 240). Successful post-World War Two memorials such as those of Jochen Gerz—what James E. Young calls “counter-monuments”—thus attempt “to show that the question of meaning has itself become meaningless” (p. 248).

Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz, “The Monument Against Fascism,” 1986.

Koselleck contributed essays to debates about memorializing the Holocaust in Germany that culminated in Peter Eisenman’s 2008 Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. His positions center on the ambivalent relationship between perpetrator and victim, for he notes that during the National Socialist period itself, “victim” (Opfer) referred to soldiers who sacrificed themselves for glory of the Reich, whereas after the war it came to symbolize senseless and passive death. Memorials to the First World War that had been repurposed in the service of Nazi propaganda were once again altered by the Allied occupiers: “References to fame and honor were removed, heroes were transformed into victims or the dead” (p. 223). To the extent that such memorials honored both war and terror in conjunction, they represent “a kind of despairing meaningless…more a loss than a founding of identity.” New “rituals” like painting over soldiers’ memorials with words such as “never again war” signal piling up layers of meaning but also breakthroughs into new forms of historical consciousness.

Koselleck was adamant about three points in Germany’s debates about remembering the National Socialist past. First, he wrote that the experiences of terror and useless suffering of the victims could not be transmitted: “They fill the memory of those affected by them, they form their memories, flow into their bodies like a mass of lava, immovable and inscribed….As a primary experience, the experience of absurd meaningless burned into the body cannot be carried over to the memory of others, nor can it be transmitted to the recollection of others who were not affected” (p. 241). He thus concluded that there was no German “collective memory” to speak of. One is confronted here with the senselessness of Koselleck’s own wartime experience: he served as a young Wehrmacht soldier on the Eastern Front and likely would have followed the fate of his brothers to the grave had he not been spared from battle by an injury. After the war he was taken prisoner by the Soviets, who held him on a work duty at Auschwitz and then in a prisoner of war camp in what is now Kazakhstan.

Second, Koselleck wrote, Germany had what his teacher Karl Jaspers called a unique political responsibility to remember not only victims of National Socialism, but also the perpetrators who carried it out its crimes (p. 245). It is no accident that Koselleck’s personal copy of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism, held at the DLA in Marbach, is almost entirely underlined and littered with annotations: political responsibility after the war entailed coming to terms with Germany’s genocidal past and pursuing justice for the victims where possible. Koselleck thus objected to the inscription on Käthe Kollwitz’s Neue Wache memorial for victims of National Socialism in Berlin, “To the Victims of War and Tyranny,” because it “disguises what happened and ignores the brutal and absurd truth of our history.” Instead he proposed: “To the Dead: Fallen, Murdered, Gassed, Died, Missing.”

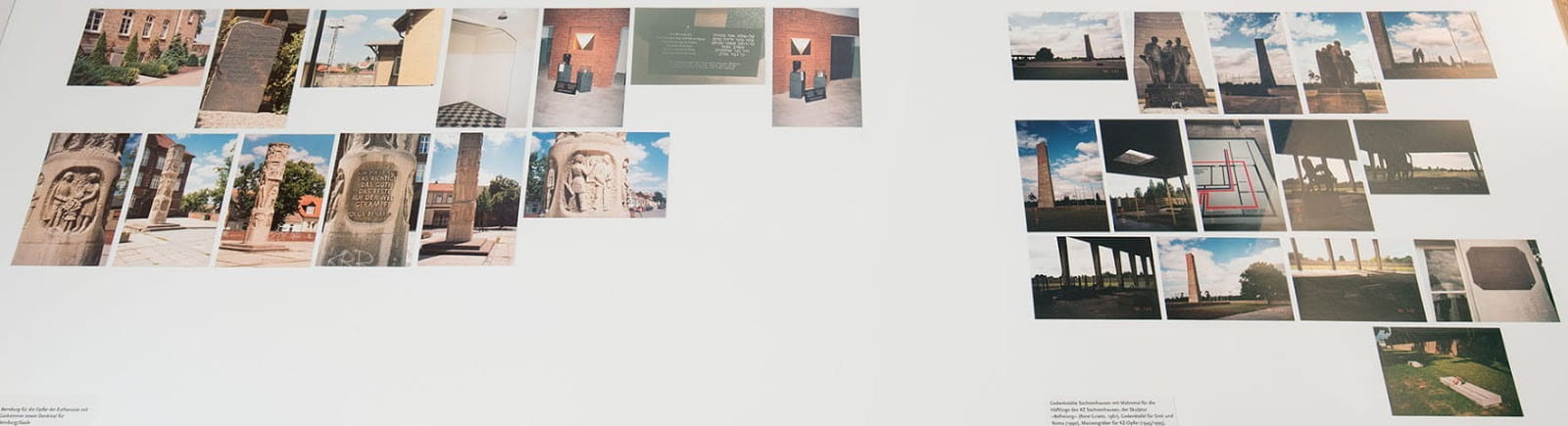

Finally, Koselleck argued that memorializing victims by same the “racial-zoological” criteria of the SS according to which they were sorted and killed only served to reproduce Nazi identity politics (p. 241). Instead he advocated a single memorial that would honor all victims of National Socialism, not just Europe’s Jews: “We as perpetrators are obliged to treat the other groups in the same way, because we killed all the victims in the same manner…. A perpetrators’ monument [Tätermal] should memorialize all the murdered” (p. 244). Koselleck worried that for Germany to focus on remembering Jewish victims like any other nation served as a “kind of unburdening” from memory of their own past as Germans (p. 246). He presciently noted that after the memorial to European Jewry was completed, Germany would be uniquely obliged as a perpetrator nation to erect separate memorials for Sinti and Roma, homosexuals, and victims of the euthanasia program, who, indeed, have since been remembered by smaller monuments nearby. Notably absent from this list, Koselleck noted, are the 3.5 million Soviet prisoners of war who died in German camps. “Mourning,” he contended, “is not divisible” (p. 245).

Euthanasia memorial and Sachsenhausen concentration camp

This need to simultaneously remember German, Jewish, and other historical subjects in the Second World War produced an aporia of memory that Koselleck argued could only be symbolized through monuments, not resolved by them. Hence the most successful memorials to both the Holocaust and German war losses, he wrote, were “negative monuments” or “process monuments,” which symbolized the senselessness of National Socialist terror and an ongoing need for working upon the past. Rather than healing wounds, such monuments serve to expose them and keep them open to public memory, debate, and historical consciousness.

Memorial at Treblinka death camp in Poland

“Koselleck und das Bild” is a striking testament to Koselleck’s visual legacy. His decades-long engagement with visual culture reminds us that images and icons are indispensable points of crystallization for historical experience and memory. Only with the tools of a historical aesthetics can we begin to heed Koselleck’s call to work through the aporias of historical memory that continue to confront us today: “we must think the unthinkable,… learn to speak the unspeakable, and… attempt to imagine the unimaginable” (p. 246).

Photographs by Reinhart Koselleck are courtesy of the Koselleck family and © Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte – Bildarchiv Foto Marburg. Photographs of the Bielefeld exhibition “Koselleck and das Bild” are courtesy of Philipp Ottendörfer.

Jonathon Catlin is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at Princeton University. His dissertation in progress provides a conceptual history of “catastrophe” in modern European thought, focusing on German-Jewish intellectuals including the Frankfurt School of critical theory.

1 Pingback