by contributing author James Farquharson

‘[t]he lack of American diplomatic initiative [in the Nigerian Civil War] is very apparent. The will to clear the “political hurdles” in this genocidal tragedy lies lost somewhere in the swamps of the Mekong Delta’. Washington Notes on Africa, American Committee on Africa, December 1968.

On the evening of the 15th October 1969, Senator Eugene McCarthy strode on the stage at the Philharmonic Hall in New York. The senator from Minnesota, and former Democratic presidential candidate, was one of the main speakers at an ‘Evening for Biafra’ a sell-out concert to raise awareness about the humanitarian emergency sparked by the outbreak of the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970). Alone on stage, McCarthy delivered a short, sharp rebuke to the policies adopted by the erstwhile Johnson and the current Nixon Administration towards the civil war. ‘We want to change American policy on Biafra’, boldly declared McCarthy, ‘[i]t doesn’t take much analysis to come up with a position on Biafra. Two million have died in over two years of war. That alone is enough to warrant a change in policy’. The so-called Republic of Biafra, the Eastern Region of Nigeria whose secession had prompted the outbreak of hostilities needed to be supported argued McCarthy, both in the provision of humanitarian aid but also politically. ‘If you support Biafrans’ intoned McCarthy, ‘you must support Biafra’.[1]

1968 Eugene McCarthy for President Flyer

McCarthy’s challenge to American foreign policy in Nigeria channeled the same energy that drove his quixotic primary challenge to President Lyndon Johnson in New Hampshire in March 1968. Running on an anti-Vietnam War platform, McCarthy condemned the escalation of the war in Vietnam, a war that by January 1968 looked increasingly unwinnable following the massive communist offensive which had shattered the notion espoused by the White House that victory was imminent. Although McCarthy did not win the primary, in gaining 42% of the vote he undermined Johnson’s standing within the Democratic Party which ultimately led to Johnson’s decision not to run for a second term. McCarthy continued to condemn the Vietnam War and, in a speech on the floor of the Senate in March 1969, McCarthy linked that conflict to Nigeria, declaring that ‘[i]t is time to re-examine our policy of “One Nigeria”, which has resulted in our accepting the deaths of a million people as the price for preserving a nation that never existed. The pattern of American diplomacy in this area is a familiar one, not that different from that in Vietnam. It began with misconceptions, was followed by self-justification, and is ending in tragedy….’[2]

The year both the Vietnam War and the Nigerian Civil War reached their punctum, 1968, was crowded with dramatic events. While Tet didn’t lead to the overthrow of the anti-communist regime in Saigon, the dramatic offensive undermined the American war effort and fed increasing domestic unrest. In July 1968, photographs and television images of mass starvation in the blockaded Biafran enclave caused a global outcry. Reports of a potential death toll in the millions and images of skeletal children, drew unnerving comparisons with the Holocaust. Historian Brian McNeil has noted that ‘Biafra and Vietnam were connected by visions of morality’. The excesses of U.S involvement in Vietnam, that included the unrestrained use of force, massive human rights violations, and support for an authoritarian regime promoted American politicians, civil rights leaders, journalists and academics to view the American response to the Nigerian Civil War as a way for the U.S to reclaim ideals and virtues lost in Indochina. The radical historian Eugene Genovese, writing as fighting raged in both warzones, acknowledged that Vietnam had caused a ‘spiritual crisis’ that had shattered ‘our celebrated sense of national virtue and omnipotence to crumble’. This article aims to show that although very different conflicts, one driven by the exigencies of the Cold War the other by tribal and religious tensions within the Nigerian polity, the two became enmeshed in the minds of many Americans as they questioned the United States role in the world. One such organisation that saw the Nigerian Civil War as an event that would reshape American foreign policy was the American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive (ACKBA).

ACKBA, the largest NGO dedicated to providing humanitarian relief for civilians in the warzone, was an organization that aimed to mobilize American public opinion in favour of a values-based foreign policy. Founded by the British-born chemistry student Paul Connett, a former campaign worker on Senator McCarthy presidential campaign, the aim of the organization was not only to raise awareness about the humanitarian emergency in Nigeria but to also challenge the Cold War foundations of American foreign policy. ACKBA was staffed by many former Peace Corps volunteers that had served in Nigeria. According to these members, ACKBA embodied the third goal of the Peace Corps in that it emphasised the importance of bringing ‘back to the American people insights into our international obligations and to educate citizens to undertake purposeful action’. If Vietnam had sapped this sense of idealism and mission, Biafra offered, according to the ACKBA, the opportunity for the United States to redeem itself.

Simon Anekwe, the Nigerian-born columnist for the New York Amsterdam News, called on the U.S government and the American public to adopt the moral attitude of the recently-deceased civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in approaching the civil war in Nigeria. In his Riverside speech, on 4th April 1967, King had insisted that the American war in Vietnam was immoral and needed to be ended by non-violent means. He declared that ‘Now it should be incandescently clear that no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war. If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read “Vietnam.”’’ King emphasized that Vietnam was part of a broader American attitude towards the world that placed a premium on anti-communism and the protection of American economic interests. While he was critiquing the war in Vietnam, he was also organizing with his fellow civil rights leaders in the American Negro Leadership Conference on Africa (ANLCA), a peace mission to Nigeria to help bring the warring parties together to resolve the conflict. Although the mission never accomplished its stated goal, due to the assassination of King in April 1968, Anekwe saw King’s ‘concept of peace and justice’ as applicable both in Vietnam and Nigeria. The Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe recalled in his memoir that the arbitration of Dr King and the ANLCA during the Biafran struggle was ‘an intervention that brought succour to millions and helped place a moral lens on the atrocities taking place in my homeland’.

While supporters of the provision of humanitarian aid and Biafran independence were not calling for U.S combat troops to be deployed to West Africa, voices were raised about the prospect that humanitarian intervention could inadvertently lead to U.S involvement akin to Vietnam. Two of the most prominent spokesmen were two of the highest-ranking African American politicians in the country, Congressman Charles Diggs and Senator Edward Brooke. Diggs challenged Senator McCarthy’s linkage between Vietnam and Biafra. In an interview published in the Afro-American he stated that he cannot ‘equate it with Vietnam’. For Diggs, the humanitarian crisis in Biafra was heartbreaking, but the morality of provided massive humanitarian relief or supporting Biafran independence on moral grounds came with untoward consequences to post-colonial Africa. Senator Brooke, who had adopted a relatively nuanced stance on the war in Vietnam, increasingly worried about how calls for the United States do to more in Biafra could lead to ‘a Vietnam type of situation’. Brooke rebuked his fellow Senator Edward Kennedy, who called for the United States to unilaterally provide aid to Biafra, declaring that ‘Kennedy and I differ on the political involvement in Biafra… I fear a Vietnam-type situation if the federal government should intervene in the problems of a sovereign country, Nigeria’. Brooke warned that ‘[I] don’t think the United States should be the policeman of the world’.

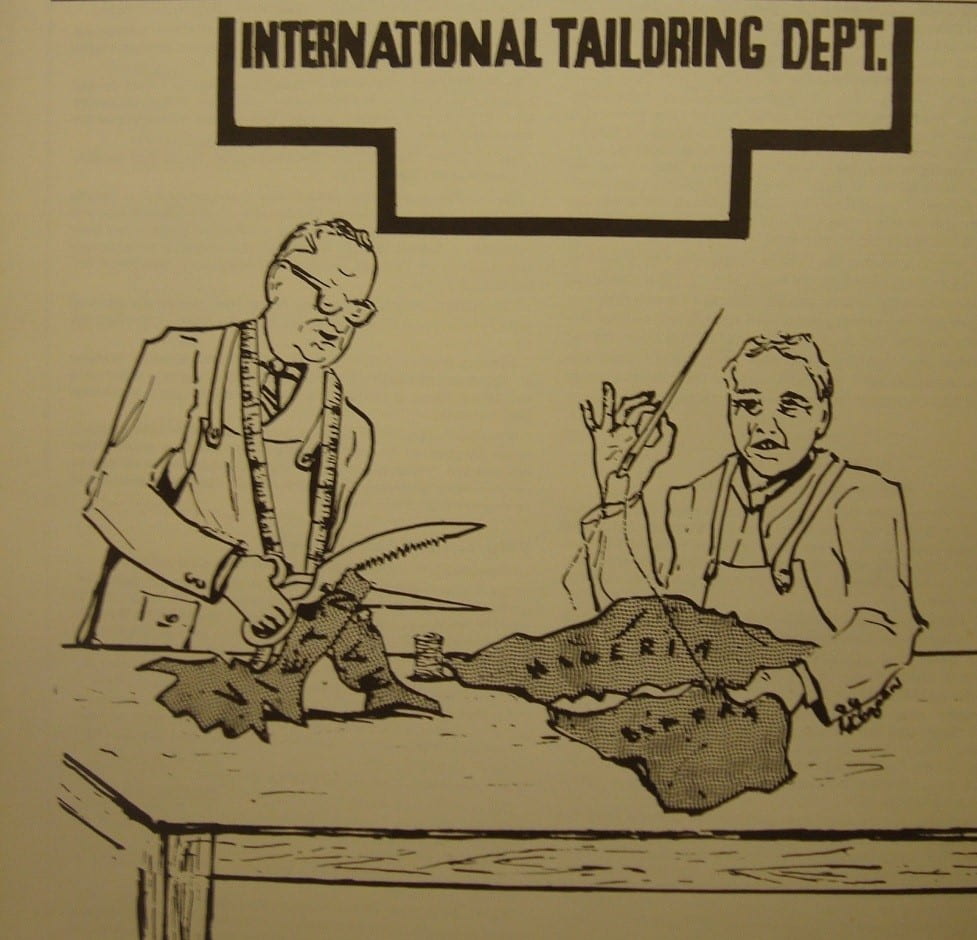

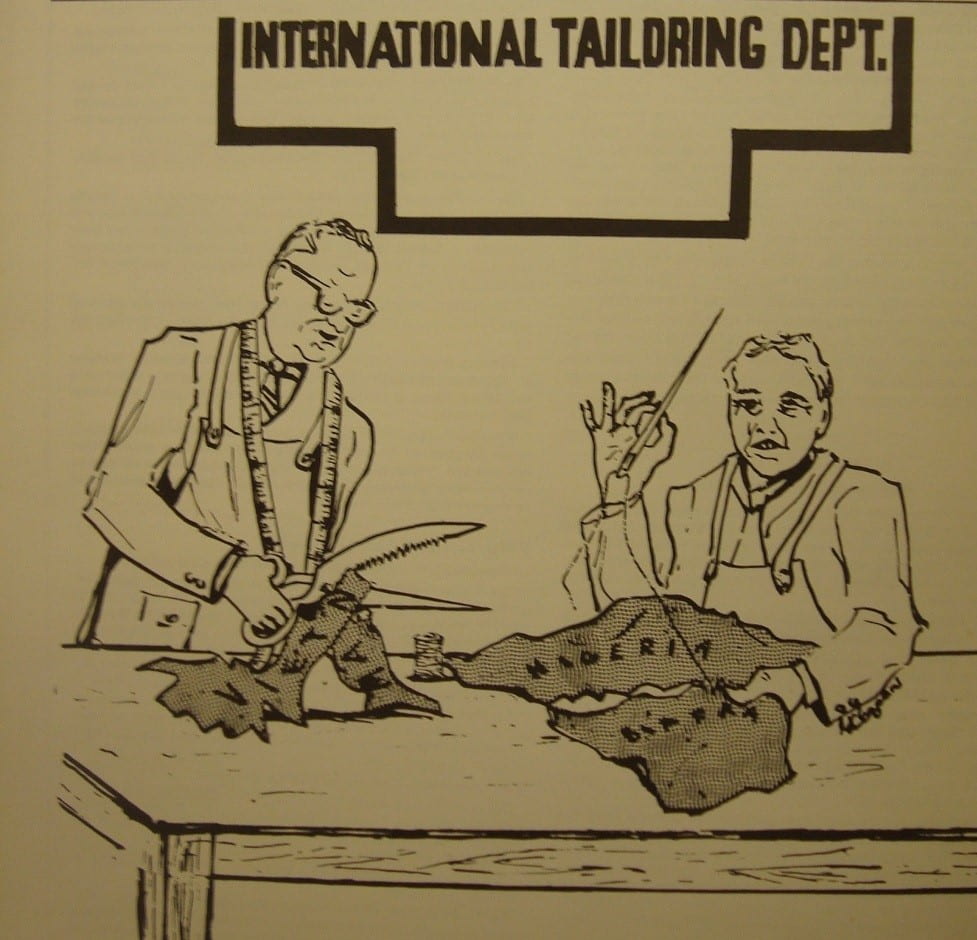

If some Americans saw supporting humanitarian aid and even Biafran independence as a way to return morality to American foreign policy, and others saw further intervention – even on humanitarian grounds – in the civil war as a recipe for a repeat of the horrors of Vietnam, a cross-section of individuals and groups in the United States endorsed the idea that the ongoing self-determination struggles in Biafra and Vietnam were interlinked. In the Biafra Review, a booklet produced by pro-Biafran activists, a cartoon titled ‘International Tailoring Dept’ depicted President Johnson deliberately cutting Vietnam in half while hard at work next to him British Prime Minister Harold Wilson methodically sewed Nigeria and Biafra back together. ‘In the eyes of the new colonialism of Russia, Britain and America’, stated an editorial in the same issue of the Review, ‘the Biafrans, like the Vietnamese, are “contaminated” with the virus of national liberation’.[3]

‘International Tailoring Dept.’, Biafra Review, January 1969, New York, File Biafra Government publications, Box 7, Clearing House Nigeria-Biafra, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

In depicting Biafra as a vital link in the ongoing struggle of the Third World, Biafran supporters were tapping into a growing sentiment in the United States, particularly amongst New Left activists, that the United States was a reactionary great power intent on snuffing out indigenous struggles for self-determination in Vietnam but also in Biafra – through its failure to provide humanitarian aid, its support for continuing British arms shipments to the Nigerian government and its failure to diplomatically recognize Biafra. The Africanist Stanley Diamond wrote in an essay The Biafran Possibility that ‘[t]he subcontinent [of Africa]…remains subject to continued manipulation from abroad’ due to ‘traditional societies [that] have been shattered, and there is no revolutionary thrust to transform and heal them in the future’. ‘Biafra’ according to Diamond, ‘has the potential to become the first viable black state in Africa and the crystallizing center around which a modern Africa could built itself’.[4]

The Joint Afro Committee on Biafra (JACB), a small but vocal group of African Americans that supported Biafran independence saw the struggle in West Africa not only as important for the broader Third World but also to African Americans. According to Mary Umolu and Shirley Washington, two of the key organisers of the JACB, Biafra was a symbol of ‘Black Power’ because it showed that ‘[Biafra was] a threat to the International white power structure and they have shown through their courage and blood in the past two years that they are capable of with-standing all the modern weapons the white world can throw at them. For it is a simple fact that the Biafrans are not fighting Nigeria but rather the great white powers of the world’.

In a year when revolutionary events reverberated from East to West and from the Global South to the Global North, the civil wars in Nigeria and Vietnam became conjoined in the mind of many Americans. Although the similarities between the conflicts was minimal in terms of origins, the course of the struggles, and the implications for the broader world, ‘Biafra’ and ‘Vietnam’ became synonymous with a broader debate about the United States’ role in the world. In 2018, as great power rivalry looms ominously in world politics, as humanitarianism and human rights are neglected, as American military interventions continue throughout the Greater Middle East, and growing numbers of Americans question the morality of these campaigns, the reoccurring dilemmas of Biafra and Vietnam in 1968 remain as important as ever.

[1] ‘Biafra benefit huge success’, Biafra, October 17, 1969, New York, File 3 American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive, Box 10, Clearing House Nigeria-Biafra, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

[2] ‘McCarthy and the media’, Current News from and about Biafra, May 19, 1969, New York, File 3 American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive, Box 10, Clearing House Nigeria-Biafra, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

[3] ‘Biafra and Vietnam: Victims of exemplary wars’, Biafra Review, New York, File Biafra Government publications, Box 7, Clearing House Nigeria-Biafra, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

[4] Stanley Diamond, ‘The Biafran Possibility’, Biafra, undated, New York, File 4 American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive, Box 10, Clearing House Nigeria-Biafra, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

James Farquharson is a PhD candidate on an Australian Postgraduate Award at the Australian Catholic University. He holds a Master’s degree in American diplomatic history from the University of Sydney. He is the author of a chapter on African American and the Nigerian Civil War in Postcolonial Conflict and the Question of Genocide: The Nigeria-Biafra War, 1967-1970 (Routledge).

Leave a Reply