by guest contributor Jake Newcomb

Several scholars published essential works in the past decade that excavate the history of mass incarceration in the United States. Scholarship by historians Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Heather Ann Thompson, and Kelly Lytle-Hernandez have helped to create an emerging historiography of the carceral apparatuses of the United States. These new histories explore the origins and developments of the United States prison system, criminal justice system, police practices, and the structural causes of crime. A major focus of the new scholarship is the history of unjust state violence and incarceration that targeted African-Americans. The discrimination against African-Americans and inmates in general, throughout American history, led to protests against the police, prisons, and the judicial system.

Many works in this new historiography recount stories of musicians who have likewise protested unjust incarceration and state violence. These new works have analyzed two specific types of protest musicians: legendary American musicians that used their music to protest alongside inmates while, at the same time, innovating the genres of the blues, country, and rock; and inmates who used music as a tool to accompany their more direct forms of protest. One such example of a legendary American musician, is, Bessie Smith. Smith played a significant role in popularizing the blues in the 1920s and made more profit than every other black entertainer at the time, partly because she ridiculed social norms in her music. Smith’s brash performances and sharp lyricism that critiqued poverty, gender roles, and violence resonated with a national audience, which thrust her into the spotlight. Sarah Haley’s book No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity gives context to Smith’s activism with the argument that black women in the postbellum South were subjected to “gendered racial terror.” Which often manifested in violence, racism, unjustified incarceration, and sexual assault. (Haley, 3) These forms of violence and incarceration helped create the gendered logic of Jim Crow, and further justified the exploitation of black women. According to Haley, Bessie Smith and other women who played the blues denied the legal validity of gendered racial terror by openly protesting prisons and the judicial system in their lyrics. They recognized its moral illegitimacy and used its existence as a target in their lyricism.

Bessie Smith (1936) by Carl Van Vechten.

The blues was, according to Haley, “sonic sabotage” that called into question the moral reasoning behind the punishment of African-Americans. The women blues musicians that Haley analyzes, including Bessie Smith, created an “imaginative world of carceral dismantling, not by merely recounting the terror of gendered regimes of imprisonment but by challenging the very foundations of ideologies justifying carceral control.” (Haley, 214) Songs like “Sing Sing Prison Blues” by Smith and “Booze and Blues” by Ma Rainey damned the judicial system and prisons as institutions that wielded unjust power. The lyricism of Smith, Rainey, and the blues, in general, expanded beyond critiquing carcerality, but Haley’s analysis indicates that this thematic element in their music was key to the construction of the “blues epistemology.” “Blues epistemology,” theorized by the late Clyde Woods, countered and condemned the logic of white supremacist ideology that expressed itself through Jim Crow. Musicians who practiced genres of music that were heavily influenced by the blues continued to use the medium of music as sonic sabotage.

Rock and country musicians in the mid-twentieth century, like the blues musicians who preceded them, also used their music to protest prisons. Julilly Kohler-Hausmann argues in Getting Tough: Welfare and Imprisonment in 1970s America that in the late 1960s and early 1970s preeminent musicians of the era aligned themselves with movements determined to alleviate structural injustices of the judicial and prison systems. In February of 1968 organizers inside of and outside of San Quentin prison in California called for a strike among the prisoners to unite and demand better living conditions. The Grateful Dead, a pioneering rock group who had formed a few years earlier, played live outside of the prison to an audience of inmates on strike, and activists showing support

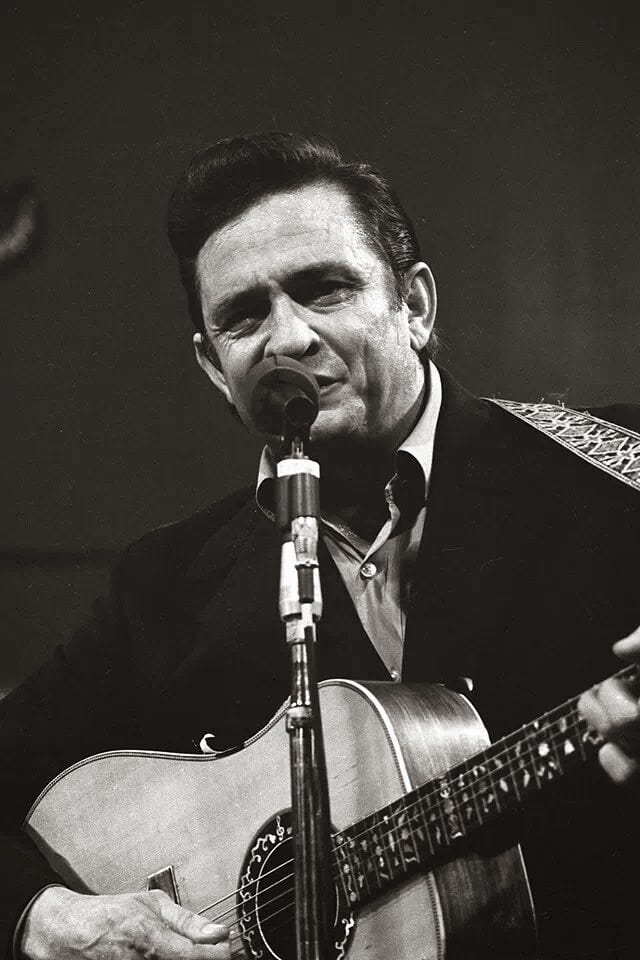

Johnny Cash at San Quentin, 1969.

outside the prison. A year later, Johnny Cash played a concert within San Quentin for the inmates. Throughout the performance, which came a year after his famed performance at Folsom Prison, Cash “explicitly allied himself with the prisoners and often in stark opposition to the state, mainstream society, and prison administrators.” (Kohler-Hausmann, 230) He debuted a song called “San Quentin” which he sang from the perspective of an inmate of San Quentin. The lyrics severely criticized the psychological effects that the conditions of the institution had on inmates. Both the Grateful Dead and Johnny Cash used their platforms to ally themselves with the late 1960s movements that fought to create better living conditions for inmates. Both the Grateful Dead and Johnny Cash went on to have immensely successful lifelong careers while fundamentally changing the nature and direction of American rock and country music, respectively.

Inmates themselves used music as a medium to accompany more aggressive and concrete forms of protest and resistance. Dan Berger and Toussaint Losier argue this in Rethinking the American Prison Movement. Tennessee miners and inmates in the 1890s protested the actions of Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (TCIC) because they used forced prison labor in order to maximize profit, a phenomenon known as convict leasing. Convict leasing kept wages low for free laborers, and forced labor upon predominately African-American inmates. Inmates performed work songs that ridiculed the convict lease system in tandem with practicing more aggressive forms of resistance, specifically, targeted bombings of TCIC’s infrastructure. Tennessee abolished laws that allowed convict leasing in 1895 because miners and inmates continuously staged dynamite attacks against the infrastructure of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company. The musical protest itself did not end convict leasing in Tennessee, but it accompanied the resistance. Berger and Losier describe the music of these inmates as a part of a lexicon of non-violent protest against the TCIC, a lexicon which also included feigning illness to avoid forced labor, not working at all, purposefully breaking mine equipment, and running away. These non-violent forms of protest were addendums to the staged dynamite attacks. While not explicitly stated by Berger and Losier, it could be the case that the performance of the work songs generated and preserved group solidarity among the inmates who wanted to end the convict lease system. If so, the inmates would have used these performances to maintain unity in between targeted bombings, which took place over several years.

Almost a century later, a similar phenomenon happened in Attica, New York. Heather Thompson argues in Blood In The Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy that on the first night of the Attica prison uprising, in which over a thousand inmates took control of a portion of the prison, some inmates spent the night in the outside yard. It had been the first time they had seen the night sky since before their incarceration. That first night had been so emotionally cathartic for the inmates, whose lives and bodies had been regimented by prison officials for years, that some of them cried and embraced each other. According to Thompson, inmates played music (on drums, a guitar, flute, and saxophone) outside in the yard on that first night, which could have stimulated or heightened some of the emotional catharsis that had been felt by the protesting inmates. The uprising at Attica in 1971 was significantly different than the five-year-long insurgency against the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company. It lasted only four days, the inmates tried to achieve their reform demands through negotiation with the state, and was broadcast live on the news to the entire nation. However, in both circumstances, the performance of music occupied a space in time between the main tactics of protest, the targeting bombings of the Tennessee inmates and the negotiations of the Attica inmates respectively. They are both, also, examples of how music was used a medium by inmates to bond with each other in extremely intense circumstances.

These are but a few examples of the history of musicians protesting prisons in America that have been analyzed by scholars in the past few years. Today, the United States has both the highest rates of incarceration and population of inmates. One of the first popular rock songs released this year, “Land of the Free” by the Killers, carries on this tradition of protesting incarceration. The song questions the soundness of “land of the free” as a phrase that can be used to describe the United States because of the rate of incarceration, discrimination against non-white citizens and immigrants, and the motivations of profit that expand the prison system. The new carceral historiography helps to show that contemporary music which protests incarceration, even though it might be inspired by current events, carries on an artistic legacy that stretches back over a century in the history of the United States. This emerging historiography, which is primarily concerned with the development of American criminal justice infrastructure, highlights the recurring tendency of American musicians using their musicality to protest carcerality. American musicians of different periods, styles, and geography are united in this historiography with this common theme: using music to protest prison.

Jake Newcomb is an MA student in the Rutgers History Department, and a musician. His essays on his personal experience with music can be found at jakenewcomb.tumblr.com