By guest contributor Edward Maza

In a 1953 letter, Alfred H. Barr Jr.—the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art—wrote: “in our civilization with what seems to be a general decline in religious, ethical, and moral convictions, art may well have increasing importance quite outside of aesthetic enjoyment” (204). Per Barr’s logic, MoMA’s founding marked more than an effort to build a new home for western art in Manhattan; it was an explicit attempt to reframe art as the moral and ethical source of knowledge in a secularizing world. It was, in other words, a stand-in for biblical religion.

In fact, nearly half a century before the founding of the museum, God had died in the minds of many thinkers. Friedrich Nietzsche, for one, proclaimed: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, the murderers of all murderers, comfort ourselves?” (trans. Walter Kaufmann, 181). Nietzsche lamented the loss of God as the loss of societal and individual values. Life, the philosopher observed, had no significance, no “comfort,” in a world without a priori meaning. Furthermore, the Bible had long informed a shared human experience with “roots in a continuum of tradition”—and yet, in a godless world, there ceased to be a unifying cosmic entity (Nochlin 41).

The void that God’s death created had unique resonance in the United States. As Linda Nochlin notes, there was “a sense of alienation from history as a shared past—an alienation central to the Americans’ experiencing their own condition as a purely contemporary one, without roots in a continuum of tradition” (136). In 1929, when MoMA was founded, the United States had only a century and half of shared history. In the interwar years, the US was not yet the global superpower it would become after the Second World War. The modern era was marked by a need to create a shared narrative of history and values to inform the future of the nation (Nochlin 136). The Museum of Modern Art, I contend, was an institution born of modern necessity—designed to provide a structure of shared value and meaning to undo the newfound alienation in the godless future.

The question posed by Nietzsche’s observed deicide remained contested throughout the early twentieth century. Jean-Paul Sartre centered the human subject as the source of meaning. In the modern era, Sartre argues, the individual subject is thrown into a godless world and is forced to forge a meaningful relationship with the world for himself. Sartre explains that “before the projection of the self nothing exists; not even in the heaven of intelligence: man will only attain existence when he is what he purposes to be” (quoted in Kaufmann349). There is no divine mandate that inherently imbues life with meaning and structure. Man exists innately without purpose and must actively create meaning in the world for himself through relation with the world around him. At MoMA the individual is forced to forge a meaningful existence for themselves in relation to the works of art on display. Objects are spaced apart from one another highlighting their individual importance while allowing the viewer sufficient space to view a single work of art. The works are then hung on unadorned white walls so nothing distracts the viewer from the object on display. The artworks provide a guide for the individual to develop themselves as a locus of moral thought. In an attempt to fill the void left by God’s absence in the world MoMA centered the artist as the subject of worship, assembling a pantheon of artists arranged by the curator-priests of the museum in the hallowed halls of the building on 53rdStreet.

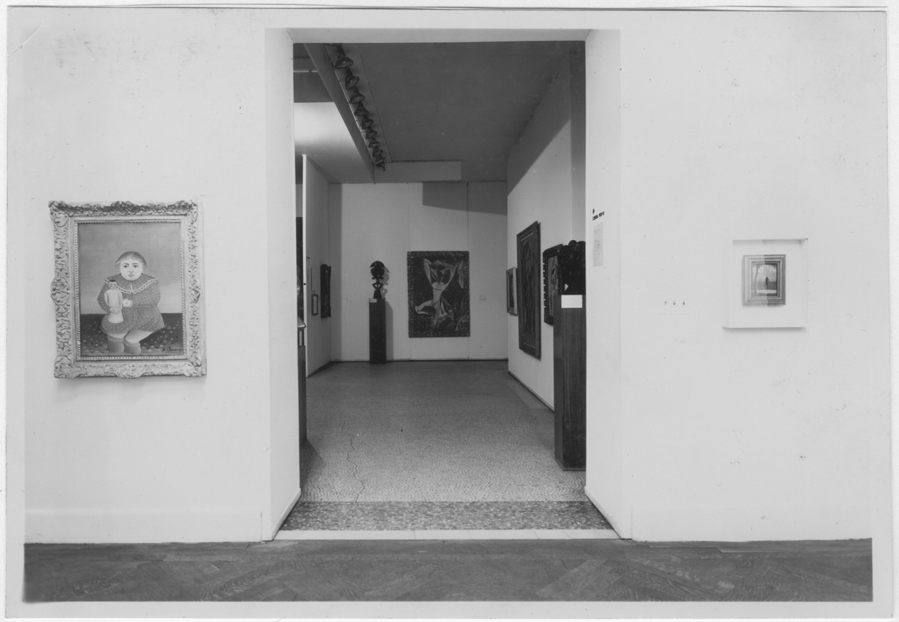

Figure 2. Photograph by Beaumont Newhall, Installation view of the exhibition, “Cubism and Abstract Art,”(including an African sculpture and works by Picasso, Rousseau, and Seurat), March 2, 1936–April 19, 1936. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN46.21.

One of the museum’s early exhibitions Cubism and Abstract Art serves as a clear example of the curatorial style established at MoMA. Paintings are hung on clean white walls, spaced apart from one another, and in a linear fashion drawing a clear teleology from Rousseau, and Seurat to Picasso. This image also demonstrates how Barr cast African art a “primitive” artform whose relevance is tied to its influence on Western painters.

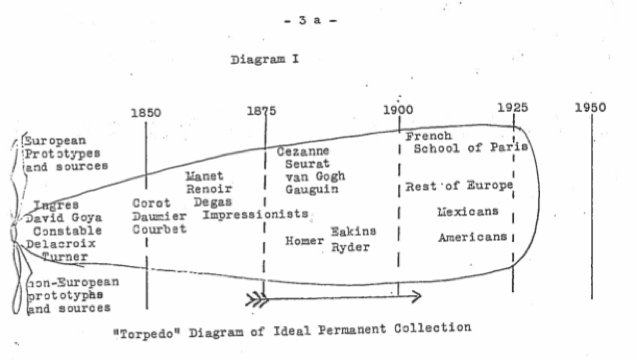

When Barr asserted that MoMA would be the definitive arbiter of artistic quality in the modern age, he constructed an art historical future in which he hoped the museum would remain focal. As the museum’s director, Barr strove to be the omnipotent force determining that history. In Barr’s 1933 “Report on the Permanent Collection,” he reveals his teleological understanding of art history in a description of the guiding principles of the museum’s acquisitions. “The permanent collection may be thought of graphically as a torpedo moving through time, its nose the ever advancing present, its tail the ever-receding past of fifty to a hundred years ago” (MoMA archives, Barr Papers II.C.17). Barr even included an image of his torpedo metaphor, anchoring the collection in the works of Ingres, Goya, Constable, Delacroix, and Turner, with supplemental influence from the general categories of “non-European prototypes and sources” and “European prototypes and sources” (Fig 1).

This diagram refers to one of the early instantiations of the theological ramifications of MoMA’s organization and collecting practices. In 1889, Henri Bergson penned his paradigm-shifting essay, “Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness,” which serves as an intellectual antecedent to the torpedo model developed by Barr. In his essay, Bergson outlined the implications of teleological readings of history for the present and for free will. In Barr’s sketch of the arc of art history, the “ever advancing present” is a direct result of the “ever receding past.” The present art scene is an inevitable fruition of the formalist innovations of the past vanguard. In his diagrammed comparison, Barr converts the passage of time into a material, spatial form: the torpedo. Bergson warned that “time, conceived under the form of a homogenous medium [space], is some spurious concept, due to the trespassing of the idea of space upon the field of pure consciousness” (98).

Barr’s Torpedo

The transformation of time into measurable space, as Barr suggests doing to organize modern art, limits the individual’s ability to make free choices, as it makes the past the basis for the future. In Barr’s organization, artistic innovation must flow linearly from the past into the present. Once an idea has been around long enough to be absorbed into the present, it is done away with as it passes through the tail of the torpedo. Bergson insists that “we could not introduce order among terms without first distinguishing them and then comparing the places they occupy; hence we must perceive them as multiple, simultaneous, and distinct; in a word, we must set order in what is successive, the reason is that order is converted into simultaneity and is projected onto space” (102). By claiming that converting time into space allows one to “project time onto space,” Bergson is arguing that this space-time can be projected onto the future, nullifying the possibility for free choice. Time, when measured in space, is predetermined.

By converting the temporal history of modern art into a spatial organization, Barr limits the possibilities of future production through the canonization of present artists. The only artists acceptable in the torpedo model are those that can find their roots in the tails of the torpedo. As time (and art history) progress, the artists who are presently the nose of the torpedo will eventually become the tail, and new artists must root their practice in the works of those sanctioned by Barr and MoMA more broadly. All future relevant “modern art” must find its roots in the works that Barr and MoMA have validated as foundational to future production. The Museum of Modern Art, led by Barr, then controls the future of modern art, predetermining what forms of art will be accepted into the canon and which will be rejected because they cannot find grounding in MoMA’s torpedo. This model is designed to outlive Barr. By rooting the development in a canon, the torpedo model insures that all future “quality” art must forever be rooted in the canon as conceived by MoMA institutionally.

In the post-modern world, the seemingly solid framework of the Museum of Modern Art begins to melt into air. Alfred Barr attempted to use the torpedo as a closed system to describe the entirety of modern artistic production. The torpedo held modern art together as a unified system to overcome the modern preoccupation with alienation in the face of the death of God. But as Derrida notes:

If one calls bricolage the necessity of borrowing one’s concepts from the text of a heritage which is more or less coherent or ruined, it must be said that every discourse is bricoleur.The engineer, whom Lévi-Strauss opposes to the bricoleur, should be the one to construct the totality of his language, syntax, and lexicon. In this sense the engineer is a myth. A subject who supposedly would be the absolute origin of his own discourse and supposedly would construct it ”out of nothing,” “out of whole cloth,” would be the creator of the verb, the verb itself. The notion of the engineer who supposedly breaks with all forms of bricolage is therefore a theological idea; and since Levi-Strauss tells us elsewhere that bricolage is mythopoetic, the odds are that the engineer is a myth produced by the bricoleur. As soon as we cease to believe in such an engineer and in a discourse which breaks with the received historical discourse, and as soon as we admit that every finite discourse is bound by a certain bricolage and that the engineer and the scientist are also species of bricoleurs, then the very idea of bricolage is menaced and the difference in which it took on its meaning breaks down (trans. Alan Bass, 258).

Barr positions himself as the engineer of modern art; claiming to establish the truths of the discourse. Barr uses the teleology from the torpedo to construct a narrative of modern art that claims to be a closed, all encompassing, system. As the museum leaves the modern era of systemic discourse into the open systems of post-modernity, its authority imbued by Barr begins to waver. No longer can the museum claim to be the authority on the closed system of modern art, as said system begins to fall apart. As the world of contemporary art expands beyond the articulated confines of the western tradition and breaks free from (and expands beyond) its western roots, it can no longer be contained by Barr’s modernist model of artistic development: “Totalization, therefore, is sometimes defined as useless, and sometimes as impossible” (Derrida 289).

In the global age, art is the ultimate form of play. It takes signs of the past and alters them to have new and expanded meaning in the present with disregard for their historical meanings. Signs and their signified meanings are loosely related to one another, constantly and unpredictably changing with the progression of dissociated time.

Edward Maza is a master’s student at Oxford in the department of Theology and Religion. His academic work focuses on the intersection of religion and art history with a particular focus on the Hebrew Bible in modern art.

February 5, 2019 at 11:29 pm

I intuited this about MoMA without fully articulating it when I first started visiting the museum as an undergrad in the early to mid 70s. At first I loved the streamlined chronological succession and the pacing the layout controlled. After visiting several times, the experience became almost musical, the narrow corridors that opened up into a large room bursting with large, colorful Matisses (and a similar burst later when you arrived at Abstract Expressionism). And the placement of the Surrealists always made me laugh, tucked in a side chapel, as it were. Even at the age of 20, I could sense the curators’ panic at what to do with these embarrassing, non-conforming relatives. Later, when I was writing about the machine aesthetic in grad school, I was surprised at how much MoMA’s installation techniques and rhetoric smacked of propaganda. And I was dismayed realizing how controlled — nearly fascist — the experience Barr created for his patrons was. The floors of the original MoMA had stripes that dictated directional flow. It irritated me. Still, when I go there now I miss that orchestrated parade, miss rounding a bend to confront the Demoiselles d’Avignon and feel the force of a change in seeing, in art making that still, because of that clever, if not all that subtle installation, felt revolutionary, 70 years after the fact. Thank you for this excellent analysis.

February 6, 2019 at 5:23 am

Thank you very much for your comment! It very clearly articulates the tension inherent in the MoMA experience and touches on what underlies the success of the institution. It will be exciting to see how the experience changes with the upcoming renovation and rehanging of the collection. I’m glad you enjoyed the piece.