By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich

This post is a companion piece to Spencer’s article in volume 80, number 1 of JHI, “Hagiography by the Book: Bibliomancy and Early Modern Cultures of Compilation in Francisco Zumel’s De vitis patrum (1588).”

He slept, and was transported. There seemed to be an olive tree of spectacular size rooted in a spacious hall, beneath which he saw himself walk, and sit down from time to time. What is more, certain solemn and noble men approached him, who said they had been sent by a great king to aid him, lest any uproot the tree beneath which he sat. Now other men came towards them, bearing axes and shovels; in the greatest haste, they attempted to uproot and unearth the beautiful tree. And yet, as they were making the attempt, the more they tried to destroy this lovely olive tree, they more they became stuck in the thickest and hardiest roots. Indeed, just then innumerable, splendid sprigs emerged from the surviving roots, filling the entire hall. (Zumel 65–66)

“He” is Saint Peter Nolasco, the thirteenth-century founder of the Mercedarians, a Catholic religious order dedicated to ransoming captive Christians. The text comes from De vitis patrum (1588), a life of the saint composed by the Mercedarian theologian Francisco Zumel and the subject of my article in JHI. I show that De vitis patrum incorporates text from nine other saint’s lives, and argue that Zumel chose these sources by opening a hagiography collection at random—that is, bibliomancy. The article explores the implications of Zumel’s divinatory method of composition for early modern authorship; here I want to highlight the consequences for the Mercedarians.

The vision of the olive tree, symbolizing Nolasco’s task to defend the Church, is easily the most striking and most substantial importation among Zumel’s appropriations. The episode comes from a 1054 life of the Benedictine reformer and bishop Saint Godehard of Hildesheim (960–1038), penned by the latter’s disciple Wolfhere. The theme itself is likely indebted to Psalm 52:8, whose speaker declares, “But I am like a green olive tree in the house of God” (NRSV).

No extant medieval source refers to Nolasco having such a vision, but after De vitis patrum this scene, and the olive tree or branch, became staples of Mercedarian literary and visual culture (see García Gutiérrez), beginning with the campaign for papal recognition of Nolasco’s sainthood. 1588 saw the end of a 65-year drought in papal canonizations; drought was followed by flood, as Tridentine Catholicism embraced the cult of the saints as a weapon against the Protestants. When, in the 1620s, influential Mercedarians began to agitate on behalf of their founder, their timing was impeccable. This high tide of canonizations was particularly favorable to religious founders, such as Frances of Rome (canonized 1608), Teresa of Ávila (1622), and Ignatius Loyola (1622) (Burke 48–62). In 1628, Nolasco joined their number, by decree of Pope Urban VIII.

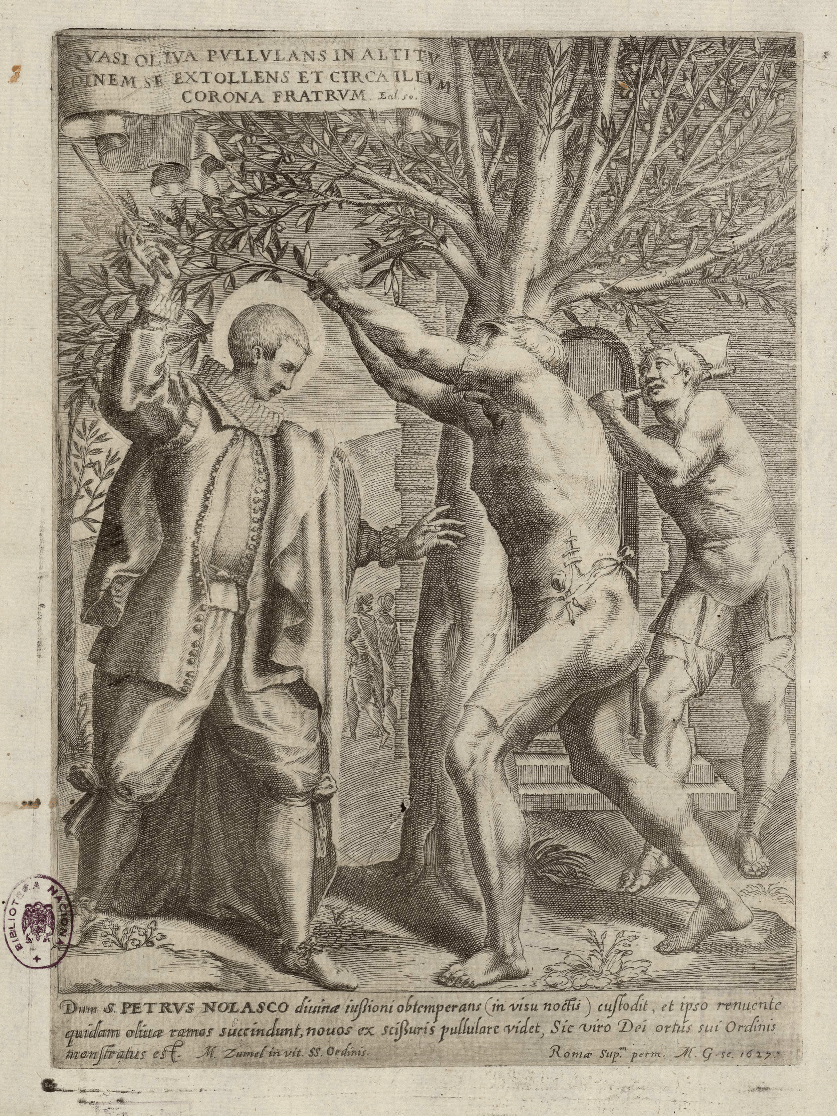

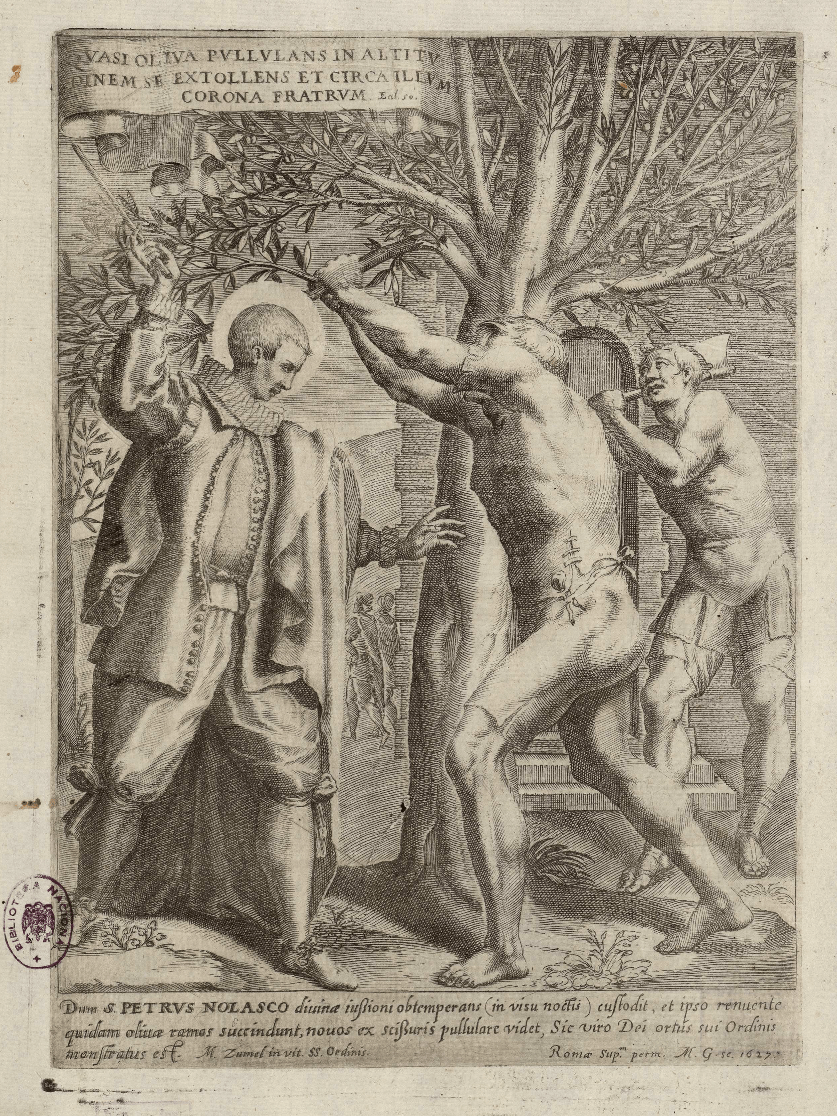

In 1956, the Mercedarian scholar P. J. M. Delgado Varela discovered a visual component to the canonization campaign, a set of engravings designed by Jusepe Martínez and executed by Johann Friedrich Greuter (see Barrera). These images, depicting Nolasco’s life and legend, are largely inspired either by De vitis patrum or by later Mercedarian authors who in turn relied upon Zumel. (Other artists employed by the Mercedarians were referred to De vitis patrum for historical material [Olson-Rudenko 71]). Mártinez understandably seized upon the dramatic episode of the olive tree.

Johann Friedrich Greuter and Jusepe Martínez, Vida de San Pedro Nolasco (1627), image 5 (Image credit: Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España).

This memorable image, capturing the saint mid-strike beneath the instantly recognizable foliage of the olive tree, not only as an illustration of Nolasco’s divine vocation but also as a demonstration of his iconographic potential as a saint-to-be.

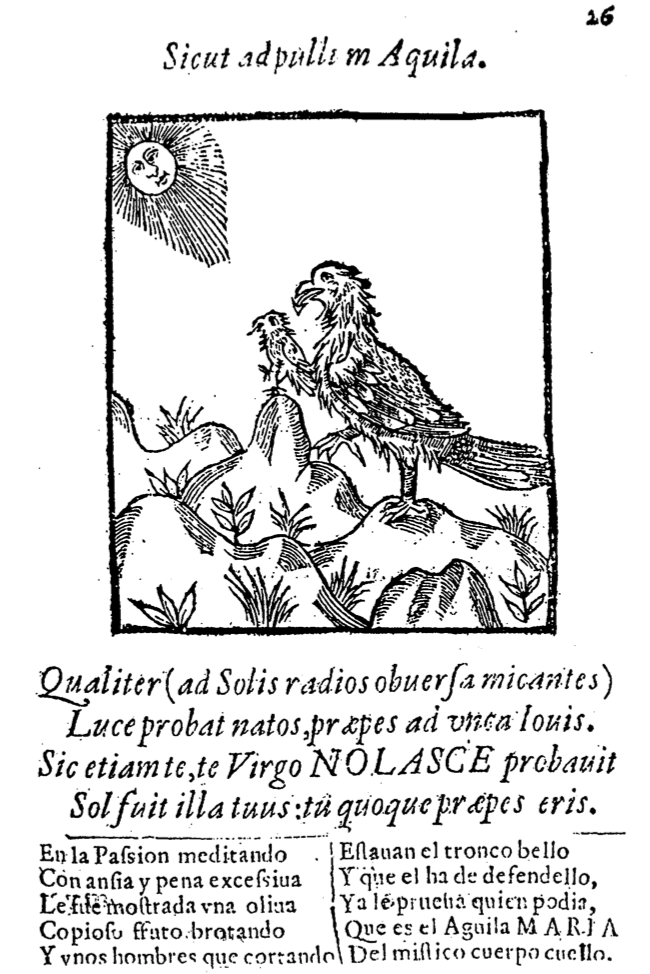

The engravings were not the only visual arguments for Nolasco’s sainthood. The same year, the Mercedarian Alonso Rémon published Discursos elógicos y apologéticos (1627), narrating Nolasco’s life in the recherché medium of a book of emblems (erudite, symbolic juxtapositions of texts and images).

Alonso Remón, Discursos elógicos y apologéticos (1627), 26r.

Remón’s sixth emblem concerns the vision of the olive tree. The Latin lemma (heading) reads, “Sicut ad pullum Aquila” (“Like the eagle to the chick”). The image is an eagle holding up a chick to the rays of the sun. Two sets of verses caption the construction: the first quatrain, in Latin, runs,

Just as (held up to the sun’s shining beams)

She proves the newborn birds by Jove’s hook;

Thus the Virgin proved you, Nolasco:

She was your sun, you will be the bird.

The second, Spanish set of verses are as follows:

Meditating upon the passion

With extreme care and woe,

He was shown an olive tree,

Budding with copious fruit,

And several men who were

Cutting away at the beautiful trunk.

And he was to defend it.

Now let all who can prove

That the eagle is Mary,

The neck of the mystical body.

Once again, the vision guarantees the divine impetus of the order’s foundation, this time following Zumel in invoking the Virgin Mary. On this score, Remón’s view was shared by a contemporary of considerably greater talents and renown: the terrifyingly prolific playwright Lope de Vega.

Lope de Vega

Lope de Vega, one of the leading lights of Spain’s literary golden age, revolutionized Spanish theater. Though best remembered today for his moral dramas, such as The Dog in the Manger (1618) and Fuenteovejuna (1619), he was no less energetic as an author of plays and poetry on religious themes. One such sacred drama was La vida de San Pedro Nolasco, premiered before the royal family in 1629 and published in 1635, the year of the playwright’s death. The play relies heavily on the standard Mercedarian narrative of Nolasco’s life, which is to say on Zumel and his imitators.

Trees begin to emerge in La vida well before Nolasco’s vision. In the first act, personifications of Spain and France take the stage to quarrel over the saint’s glory. Spain insists, “the order and the way of life that awaits Peter Nolasco, you shall soon see founded in me, as it is spread through you. A tree transplanted from where it is born to some other place” (I.402–07). France retorts, “It seems an ungrateful thing to give the fruit to some other land, for it is owed to the place it was born” (I.408–10). Spain, however, wins out with the reply, “The tree owes more to the water than to the earth, for it is heaven that sustains and irrigates it. And so, since heaven wishes to sustain it in me, do not resist its intentions” (I.411–13).

Having established Spain’s God-given prerogative, Lope de Vega can turn to the iconic moment itself. Toward the end of the first act, Nolasco recounts his dream to Pierres, a servant and comedic foil invented for La vida:

Things are different with me since I was shown a noble olive tree above a carpet of a field, so verdant in its twigs and branches that it seemed a blessing for Spain, such as the Prophet-King paints. But against it with headstrong ferocity came several frenzied men, who tore at its shoots. The heavens themselves, taking pity upon the echoing cries of the sundered branches, begged the world for aid. […] With all this I cannot rest, hoping that heaven will instruct me in something I know not, encoded within this olive tree. (I.640–55, 660–63)

A certain dramatic irony obtains, for the audience knows what the baffled Nolasco does not: he is presently to become a saint. Pierres hazards a rather crass interpretation: “Perhaps that olive tree is the sheaves of Joseph, and a day will come when your kin shall reverence you” (I.667–70). Nolasco does not even bother to respond to this (an indication that the audience may do likewise). Instead, Pierres falls asleep—onstage—while the saint begins to pray for insight.

Wondrous Virgin, the olive tree whose flowers give the oil that gives us life, immaculate dawn, who, clothed in the sun, covers heaven and earth with splendor. […] What olive tree is this, which they seek to abuse, which calls me to its aid with the tongues of leaves, while the world falls silent? (I.700–03, 708–10)

At this point, dea ex machina intervenes, in form of the Virgin herself, “upon a throne of angels drawing back a cloud.” The Mother of God supplies the correct gloss:

I am the olive tree of the field: you are the one who must take the branches of a heavenly militia for my defense. With my name and my favor, create an order, garbed in white for my unspotted purity. Imitate my son Jesus’s title of redeemer in rescuing the Christians held captive by the barbarians. This is what the savage men and the olive tree signify. (I.718–31)

This revelation colors the rest of the play, as Lope de Vega continues to weave references to the vision into the text. In the second act, Pierres describes joining the order as “having taken these branches” (II.99–100), while in the third he mentions Nolasco’s continued visions of different trees, including olives (III.20). These reprises reactivate the audience’s association between the dream, the Virgin Mary, and Nolasco’s divine mission.

My aim in tracing the olive tree’s German roots is not to play the iconoclast; far be it from me to stand in judgment upon sincere piety. And I have no doubt that Zumel wrote in the sincerest piety—he turned to bibliomancy precisely in order to let God’s providence, not his own judgment, guide the narrative of Nolasco’s life. That decision had far-reaching artistic, literary, and devotional consequences, integral to the foundation story of an order that last year celebrated its octocentenary, and counts some eight hundred friars spread across five continents. Nolasco’s spiritual children continue his defense of the olive tree.