Sarah

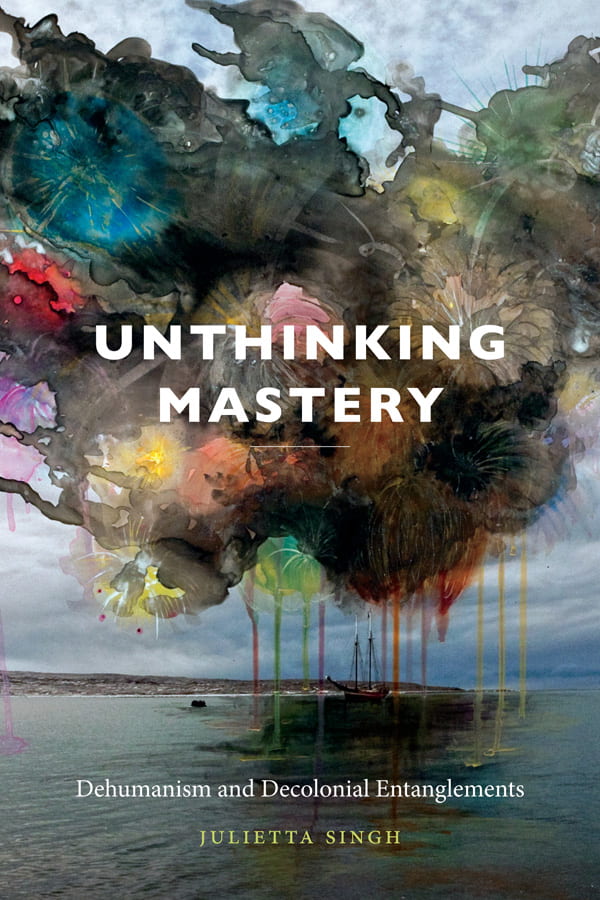

Julietta Singh, Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

From childhood we have all been warned against ‘judging a book by its cover.’ I suppose then that I should be somewhat ashamed that I first picked up Julietta Singh’s Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016) precisely because I was enchanted by the glorious colours of its cover. Luckily for me, Unthinking Mastery is the exception that proves the rule. In the introduction to this work of critical theory, Singh sets herself the task of beginning ‘to trace some of the desires and aims of mastery’ from the decolonization movements of the mid-twentieth century through the discourses of anti- and post-colonialism in order to show ‘how the cultural politics of colonialism remain intact and to trace the entanglements of ideological practice and material fact as they signal the legacies of colonialism.(2)’ She does this elegantly and persuasively, examining both political and literary discourses through the frame of two posthumanist lenses: the question of animal and new materialism. The first half of the book engages with anti-colonial thinkers who themselves are thinking through the question of mastery whilst the second builds a close reading of postcolonial literary works that embody the workings of mastery. Ultimately, Singh leaves the reader with a critical toolkit for thinking through the legacies of empire that I have certainly found very useful.

It was certainly an excellent book to read alongside my second recommendation for March: Robert Gildea’s Empires of the Mind: the Colonial Present and the Politics of the Past (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019). Whereas Singh’s work is very much a work of theory, Gildea’s is a sweeping comparative history of the legacies of empire in France and Britain. He begins the book, and indeed draws its title, from a September 1943 speech delivered by Winston Churchill. In front of a group of Harvard graduates, he declared that ‘the empires of the future would be the empires of the mind.’ Churchill was imagining an end to World War Two that allowed empires to live alongside each other in peace. It was not a vision of the future that included the fragmentation of the British and French empires. Nonetheless, as Gildea observes, the concept of ‘empires of the mind’ is a useful way of thinking about the legacies of colonialism and their continued importance for making sense of our contemporary political moment. In many ways, the book is a call to arms, a persuasive argument that the problems of our time can only begin to be resolved if the British and French are prepared to genuinely reckon with their histories of colonialism. It is, as Gildea admits, not an easy task but a necessary one. As we stare down the barrel of Brexit negotiations, I cannot help but agree.

Simon

There are many books that cover the same historical territory as Ellen Meiksins Wood’s The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (London: Verso, 2017), but there aren’t many books like it. I had seen the title recommended recently by journalists, activists and historians, all with their own reasons, and after I started reading I could understand how it manages to appeal to a mix of audiences that academic monographs rarely reach. Wood succeeds in doing two things at once that many scholars might imagine as two poles between which they have to navigate and compromise: covering dense historiographical and theoretical debates in a way that convinces readers of the profound political significance of the stakes involved. The book is not a work of original archival research, nor was Wood a historian with that project in mind. She was a political theorist who recognized that the shape of the histories we tell about the origins of capitalism and the “transition” from feudalism can lead us down particular paths in political thinking and action today. She catalogues common narratives of “commercialization” and the rising middle classes and finds again and again the same assumption embedded in each: that modern capitalism is a “natural” condition and some individual, group or class was waiting to bring it to the rest. That repetition doesn’t just uncover the pervasiveness of the premise, it also reminds the reader that accepting it has seriously constrained the possibilities for imagining political and economic systems that do not, in those stories, appear natural at all.

Wood’s argument goes beyond the critique of accounts that try to present artificial structures as natural landscapes, however. She surveys a theoretically complex and politically divisive debate on the development of capitalism in early modern Europe and intervenes to provide her own account. She argues, alongside historians like Robert Brenner, for the “agrarian” origins of capitalism, particularly in England in the seventeenth century, when landlords, large tenants and their landless laborers were all forced to charge higher rents, improve productivity and work more “industriously” to sustain themselves. None of them were the modern heralds waiting to unleash capitalism through their own natural inclination to “truck, barter and exchange,” in Adam Smith’s terms. Wood proceeds to spell out the implications of this one position in a seemingly arcane debate, grappling with difficult debates held mostly among Marxist scholars several decades ago, for the way we ought to understand pressures on labor discipline and the the imperative to political mobilization in the present. Throughout, The Origin of Capitalism disabuses readers of the unnecessary contrasts that scholars often feel they need to choose between — elegant prose and theoretical rigor, historiographical engagement and popular appeal, argumentative clarity and political urgency — and shows how they can be written together.

Spencer

There is a charming pair of expressions to describe the confessional churn between Anglicanism and Roman Catholicism: “to swim the Tiber” is to convert from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism; “to swim the Thames” is to go in the opposite direction. Though I haven’t converted to anything, I’ve been swimming the Elbe in the last few weeks, straying from my usual Calvinist environs to navigate the unfamiliar waters of Lutheranism.

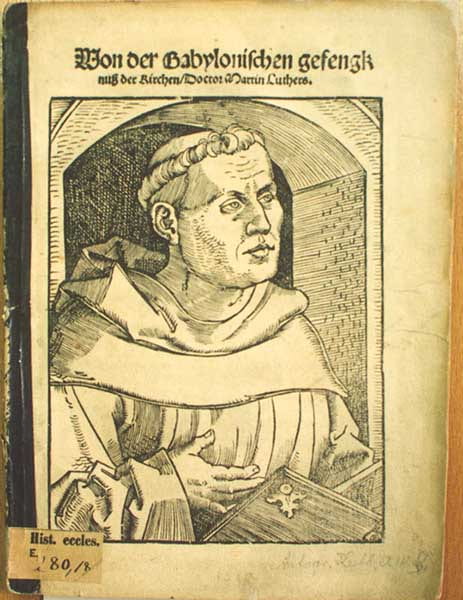

Frontispiece to On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church (1520)

From the horse’s mouth, as it were, I’ve been enjoying Luther’s Three Treatises (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1970), a collection of three landmark texts all published in 1520: To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian. Even at the distance of five centuries, the radical nature of Luther’s vision is breathtaking.

If your superiors are unwilling to permit you to confess your secret sins to whom you choose, then take them to your brother or sister, whomever you like, and be absolved and comforted. Then go and do what you want and ought to do. Only believe firmly that you are absolved, and nothing more is needed. (70)

At a stroke, Luther subverts the church hierarchy, the sacrament of penance, and generations of theology explicating the crucial role of the priest in confession. The other, sharper edge of the sword, however, is the message of consolation, as revolutionary as it is humane: confession can be a painful task, so confess to whomever you feel most comfortable talking to. And then you are free of your sins—no rites of absolution, no works of penance, no vows, “Only believe firmly that you are absolved, and nothing more is needed.” Heady stuff.