by guest contributor Shahrukh Khan

Max Weber

Max Weber was a reluctant modernist. He understood that the major social and political trends of the modern world were irresistible, but this understanding came with a tinge of regret. In January 1919, months after Germany’s unconditional surrender, Weber delivered a lecture in Munich, on “politics as a vocation.” In this lecture, Weber defined the state in his famous formulation: “Like the political organizations that preceded it historically, the state represents a relationship in which people rule over other people. This relationship is based on the legitimate use of force (that is to say, force that is perceived as legitimate).”

Though the definition of a state in these terms has been useful, it has become, as anthropologist Stanley J. Tambiah notes, “a sick joke.” “After so many successful liberations and resistance movements in many parts of the globe,” Tambiah writes, “techniques of guerrilla resistance are now systematized and exportable knowledge.” (Leveling Crowds 6). But we need not even go as far as “guerrilla resistance” to see that political violence based on, for example, religious fervor has taken hostage the notion that the state is the sole custodian of violence. Across the globe, groups and leaders with a foothold outside the confines of ‘government’ vie for legitimacy with the instruments of the Weberian state. In the postcolonial world, Pakistan is a striking example of the working through of statehood and force, particularly as its founding on the idea of religious sovereignty sits anxiously with the boundaries of state (often regarded as a secular space, in opposition to “church”) and non-state.

In this context, debates over the viability of “democracy” in the postcolonial world intersect with assumptions about the compatibility of an effective state and the presence of religious conflict. Debates about the compatibility of democracy and Islamic public morality in Pakistan often turn on the question of effective political authority, which for Weber is compromised by bureaucracy. Bureaucracy is a form of human organization that rests on norms rather than persons. But Muslims, especially those who protest blasphemous remarks against the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), may not entirely support this characterization of bureaucracy or governance. After all, for many observant Muslims, allegiance in daily life or religious practice is not to the bureaucratic state but rather to Allah and His Messenger.

However, a religious reader might find particular sympathy with Weber, because for Weber, the only way that the world could be saved was through a person who is holds a “gift of grace” that legitimizes his rule. Naturally, such reasoning has led critics like Wolfgang Mommsen to accuse Weber of being a fascist well-wisher. But “grace” as the possession of an authoritarian figure, and “grace” as a holy thing might well be in the eyes of the reader. Attending to the history of blasphemy in South Asia – and how the British attempted to regulate interconfessional life – illustrates this intersection.

For many Muslims, the Prophet holds ultimate sway in how they practice their religion. Muslims do not simply follow the Prophet’s advice or admonitions, but also “try to emulate how he dressed; what he ate; how he spoke to his friends and adversaries; how he slept, walked, and so on.” (Mahmood, Is Critique Secular? 75) Such actions and behaviors are collectively referred to as the Prophet’s sunnah, and though they are not divine commandments (Muslims hold the Prophet in a venerable, non-divine light), they are virtues that Muslims attempt to embody. As such, insulting the Prophet is not like an ornery attack on one’s family member or teacher. It is an attack on ways of being. The Prophet is a materially grounded figure (in religious signs, for example) that holds unique semiotic value as a matter of spirituality, lifestyle, and morality. The Prophet and his sunnah represent a connection between corporeality, religious practice, and otherworldliness. Put more bluntly, attacking the Prophet is not just hate speech, but an attack against an entire repertoire of sensibilities that govern proper, moral conduct and serve as a conduit for Muslims to please Allah. However, the semiotics of the Prophet’s corporeality are only part of the reason why blasphemy is so politically sensitive in Pakistan today.

The British were quick to realize that the conquest of India required dominating geography as well an epistemological terrain replete with a litany of social, religious, and political persuasions (Cohn, Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge, Bernard Cohn). Brute force and military campaigns would not work on their own. Administrators of company rule and later, of the colonial state, had to compromise somewhere, and compromise found its most robust manifestation in the allocation of legal authority.

The law is not only concerned with ending conflict but also nourishing its expansion. British colonial administration suggests a slight permutation of this argument, because it involved the allocation of power to different contingencies in Indian society – chiefs, princes, religious leaders, etc – as a way of enacting its own sovereignty. In other words, the British colonial state should be understood not through its expansion of power, but its limitations. This gave way to a system of fragmented, competing sovereignties and sources of legitimacy that presaged issues of sovereignty today.

While democratic principles of freedom would ostensibly celebrate such a “diversity” of voices, the same would not obtain for a modern legal apparatus whose legitimacy is secured by a monopoly on the means of violence. Much of nineteenth-century European academia exposited the state as omnipotent, casting it as symbolically pervasive and domineering.

Anthropology has empirically evinced this theoretical stance, against which Pakistan has often been labeled as a ‘failed state,’ as too reductive. The Pakistani state lacks the political and legal thrust, the failed state argument goes, to consolidate its sovereignty and become the sole warden of violence and physical power. And it is precisely this insufficiency that has enabled many factions to take the law into their own hands. The most prominent of these factions is the Tehreek-i-Labbaik, an Islamic political party founded by Khadim Hussain Rizvi. Its main goal has been to organize and lead street protests in an effort to secure (very) prejudicial enforcement of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws.

The distribution of power in colonial India, as it were, has made securing liberty for minorities and women in Pakistan in the present more difficult than the colonists might had have it.

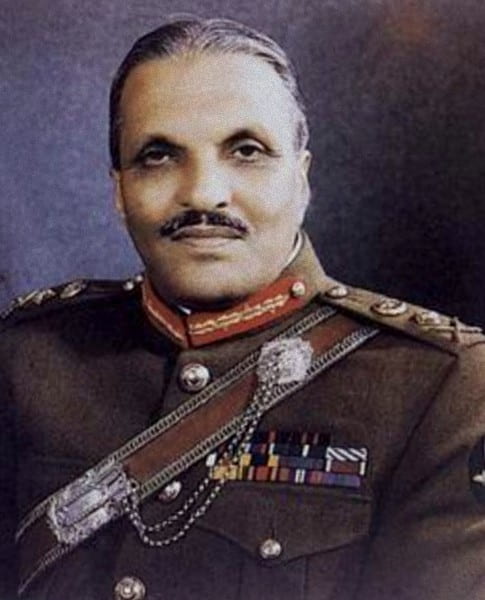

Zia-ul-Haq

The lack of the consolidation of power is what animated the Islamization project of General Zia-ul-Haq, the military dictator ruling over Pakistan during the 1970s and 1980s. Zia attempted to see Weber’s understanding of the state to its completion, with a modification: he wanted to secure state legitimacy and sovereignty on religious grounds, not secular ones.

During Zia’s rule, the Parliament added Clause 295-C to the penal code, criminalizing derogatory remarks against companions of the Prophet Muhammad and other religious figures. Punishment, initially limited to a prison term of up to three years, was expanded through a legal mandate issued by the Federal Shariat Court (FCC) in 1991. It ordered the government to remove the option of life imprisonment, leaving death as the only punishment for making blasphemous remarks.

Reading Weber’s state onto Pakistan’s blasphemy laws might seem like an eclectic pairing, not least of all because his “gift of grace” was hardly compatible with the precise ways in which the Pakistani state has taken up its so-called “religious” duties. Even so, the presence of “grace” in the authority of the state and the divine echoes of that virtue are one way to read the coming together of the authority of the bureaucratic state and the prohibition against blasphemy. The complex history of blasphemy law in Pakistan suggests that much of the violence enacted by non-state actors is filtered through the experiences and incentives of colonial administrators and post-colonial national elites whose goals were as diverse as the religious traditions they attempted to regulate.

Shahrukh Khan is a J.D. candidate at Emory University School of Law. His interests broadly focus on philosophy, secularism, and American constitutional law. He received his BA in Social Studies, with a focus in European intellectual history and linguistics, from Harvard College.

1 Pingback