By Guest Contributor John D’Amico

On April 1, 2019, the government of Japan announced the name of the new era. With the abdication of Emperor Akihito and the accession of Crown Prince Naruhito, the curtain falls on the Heisei period (1989 – 2019), and on May 1st, the new era, dubbed Reiwa (literally: “Ordering Harmony,” but the government suggested “Beautiful Harmony” as the official translation), begins.

The practice of changing era names upon the succession of a new emperor — one only established with the post-1868 emergence of a modern Japanese nation-state — might seem like an empty ritual. But the two character phrases that make up the era names are meant to “bear a meaning appropriate to serve as an ideal for the [Japanese] people,” and so serve an important ideological function (1979 Cabinet Report).

In contrast to earlier reign names, all based on phrases from Chinese classics, Reiwa comes from the Man’yoshū, the earliest extant vernacular poetry collection in Japan. It is the first reign name sourced from a Japanese work.

Critics quickly latched onto the authoritarian ring of “Ordering Harmony.” The right-wing bona fides of current Prime Minister Abe Shinzo are well known. He has called for the return of Japan to the status of a “normal” country through remilitarization and the rewriting of the postwar constitution. But what does his evocation of the Man’yoshū mean politically?

To help answer this question, it is worth quoting the prime minister’s remarks at the announcement of the new era at length.

Today, we have decided as a cabinet on the change in era name. The new era name is Reiwa. This is from the Man’yoshū passage, “An auspicious month (reigetsu), the beginning of spring. In the fine weather a fair breeze blows gently (kaze yawaragi[wa]). Plum blossoms bloom, scattering like powder before a mirror, and orchids give off the fragrance of perfume.”

Thus, “Reiwa” means that when people beautifully bring their hearts together, culture is born.

The Man’yoshū, though compiled over 1,200 years ago as Japan’s oldest poetry collection, featured poems from a broad spectrum of society: not only from the emperor, the imperial family, and nobility, but also from people like border guards and farmers. It’s a national work that represents the rich national culture and long tradition of our nation.

An eternal history and an elegant [literally: “aromatic”] culture, beautiful nature changing with the seasons. This Japanese national character should firmly be passed on to the next generations. Like the proudly blooming plum blossoms that herald the coming of spring after a long winter, each and every Japanese person, along with their hopes for tomorrow, can make their flowers bloom. That’s the kind of Japan I want to see. With that hope, we decided on the name “Reiwa.” Bearing heartfelt thanks for peaceful days where we can cultivate culture and appreciate the beauty of nature, I want to open up a path to a new era full of hope along with the people of Japan.

In spite of their classical trappings, the links drawn by Abe between poetry, social harmony, and cultural unity are of a more recent vintage. They hearken back to a pre-World War II discourse that idealized Japanese antiquity and the idea of a classless polity united under the divine authority of the emperor.

Readings of the Man’yoshū played an important role in the construction of this discourse, one that Abe drew on in his speech. The text was seen to represent an overcoming of the barriers of class and status and a repository of the raw, unfiltered emotions of the Japanese people. Abe’s appeals to culture, similarly, mirror the turn of many thinkers in the politically charged 1930s and 40s to see aesthetics as a solution to the mounting contradictions and conflicts inherent in modern life.

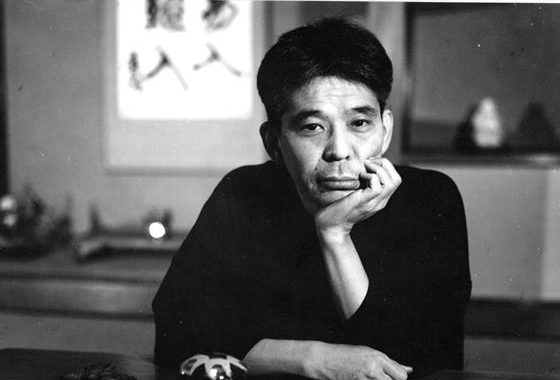

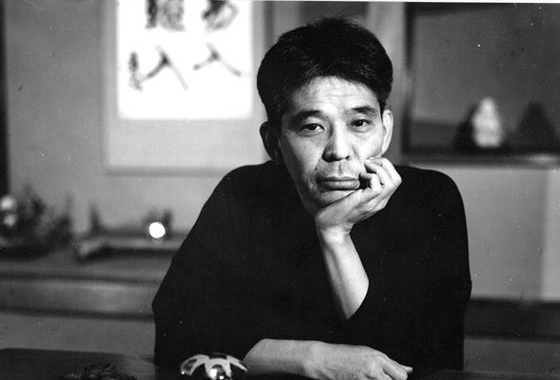

Writing in 1942, literary critic and leader of the Japanese Romantic school Yasuda Yojūrō argued in his The Spirit of the Man’yoshū (Man’yoshū no seishin) that, “In the Man’yoshū is the faith to establish the nation, expressed in a confidence in the nation itself…I felt deeply, painfully the idea behind the Man’yoshū: to protect the spirit of the nation’s history in an era of incommensurable darkness, shining forth an unextinguishable light” (426).

Yasuda Yojūrō, leader of the Japanese Romantics (日本浪曼派), writer, and literary critic. Image: Sankei News.

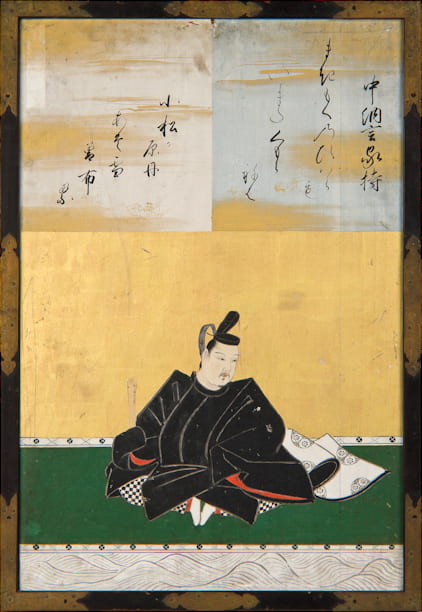

Yasuda saw in this ideal a transcendent spirit passed down from the Man’yoshū poet Ōtomo no Yakamochi (718 – 785) via the “national learning” scholars of the Tokugawa period. Yakamochi is an important figure in his own right. But in the 1930s and 40s, he was most well known among the general public for his verse Umi yukaba [If we go on the sea], set to music in a popular military song emblematic of the war years:

If we go on the sea, our dead are sodden in the water

If we go on the mountains, our dead are grown over with grass

We shall die, by the side of our lord [i.e. the emperor]

We shall never look back (trans. Cranston, The Gem-Glistening Cup, 458)

Ōtomo no Yakamochi, statesman, member of the “Thirty-six Immortal Poets,” and a compiler of the Man’yōshū. Image: Chūnagon Yakamochi by Kanō Tan’yū, 1648.

In 1942, the associations between the Man’yoshū, emperor worship, and militarism were impossible to ignore. That same year a conference on “overcoming modernity” was held by the Bungakkai (The Organization for Literary Studies), with members of the Japanese Romantics and the Kyoto School of philosophers also in attendance. Many of the participants saw their enemy as the relentless process of history itself. The Man’yoshū’s status as a repository of tradition and source of authenticity made it a potent tool in the hands of those searching to turn away from the contradictions of contemporary life and embrace a transhistorical “Japanese spirit.”

Yasuda did not participate in the conference, however. Philosopher Karatani Kojin contends that Yasuda sought instead to “overcome” the modern through an active rejection of “interest” through aesthetics, cultivating a detached “romantic irony” that spurned explicit ideological motivations. (Senzen no shikō 110-1) To participate in any kind of coherent, practical project would stink too much of “interest” for Yasuda. In Karatani’s words, Yasuda saw the war as “nothing more than an occasion for poetry” (111). This reading makes Yasuda, a former Marxist, more an amoral aesthete than a full-throated militarist.

What he shared with the conference participants, in the historian Harry Harootunian’s words, was “…a dangerous kinship with fascism in its desire to bracket history and hence the development that had propelled the country to its present in order to represent Japan as fixed and eternal. In all of those discussions about an ineluctable ‘spirit,’ the symposium shared with the prevailing discourse on cultural authenticity the fantasy that neither history nor techno-economic development had managed to change what was essentially and eternally Japanese” (Overcome by Modernity, 40).

Abe also wants to share in this fantasy. Cloaked in the language of valuing a rich “cultural life,” his remarks seem almost innocuous. But they speak to the enduring desire to transcend the modern through a retreat into the classical past, an impulse that should give us pause in light of its dark history.

John D’Amico is a second-year PhD student in history at Yale University. His research focuses on merchants and commercial networks in early modern Japan.

May 1, 2019 at 6:42 am

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.