By Contributing Writer Sara Friedman

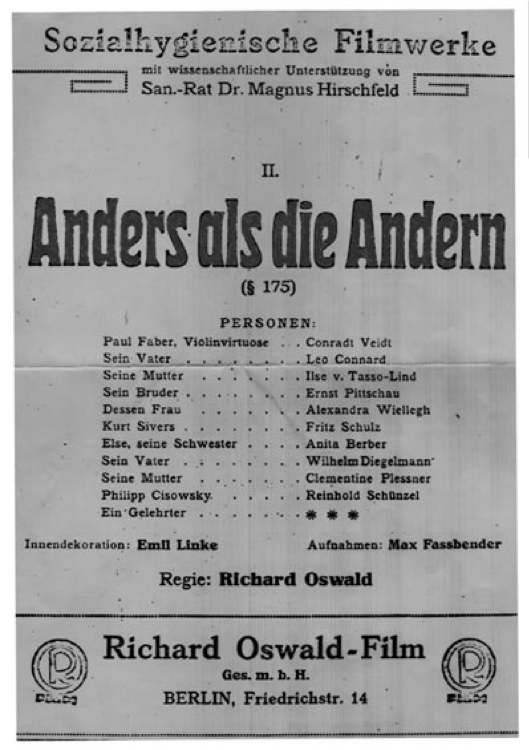

On May 28, 1919, the first gay rights film was released in German theaters. Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others) follows the story of a homosexual violinist who is blackmailed and forced to commit suicide once his orientation becomes public knowledge. It is also a love story; the violinist comes to terms with his sexuality with the help of a sexologist played by the real-life Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, and a relationship blossoms between the violinist and one of his students. Through an in-film lecture, Hirschfeld develops an argument that bears repeating a century later: variance in sexuality, gender, and gender expression are natural and normal – the problem is societal intolerance.

How was a gay rights film made in 1919? In Germany?

Germany had a well-established gay rights movement dating from the mid-19th century. With the German Empire’s 1871 unification and adoption of the Prussian penal code, a sodomy provision (Paragraph 175) became national law. Scientists, cultural figures, and even August Bebel, leader of the Social Democratic Party, fought to repeal the law. In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific Humanitarian Committee) in Berlin (where the police were relatively tolerant of homosexuality) to advocate for the rights of sexual minorities.

Anders als die Andern continued this decades-long campaign through new means. On November 12, 1918, three days after the German republic was (twice) proclaimed, the provisional government abolished censorship, even for the new medium of film. Before censorship was reintroduced in May 1920 – and only for film – a genre optimistically known as “Aufklärungsfilme” (literally “enlightenment films” but more accurately “sex education films”) flourished They included all manner of “risqué” films, from earnest attempts to address and rectify societal problems such as prostitution to what amounted to early 20th-century clickbait – films with titles like Hyänen der Lust (Hyenas of Passion). Some, like Anders als die Andern, were produced under medical supervision, a testament to the didactic power moving images were assumed to have. The term would specifically be linked to the Vienna-born director-producer Richard Oswald (director of Anders als die Andern), who packaged arguments for social reform in a feature-length format suitable for entertaining mass audiences.

silentfilm.org [San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Different from the Others, A Day of Silents 2016]

New medium, new republic

Film at the time of Anders als die Andern’s release had established itself as mass entertainment. With their bold, blunt messages, the Aufklärungsfilme imagined new roles for the medium. They also posed a possibly existential threat to the art form’s fragile respectability. In virtually every article on Anders als die Andern in German newspapers, sexual minority or scientific journals, and film magazines, the film’s aesthetics and plot were barely discussed. Instead it became an excuse to talk about something else. Between Anders als die Andern’s release and the Lichtspielgesetz, unconscious fears bubbled up for the future of the new German republic.

Critics, perhaps expectedly, took offense at Anders als die Andern’s subject matter. The Film-Kritik commentator B.F. Lüthar was one of the first to review it. His article “‘Anders als die Andern’: the new Aufklärungsfilm” appeared only three days after the premiere. For someone claiming to be baffled, verklempt, rendered speechless (“indeed, I don’t know what I should say”), his prose is surprisingly voluminous. On whether the topic is appropriate for film, he said “well, it’s done, it’s been decided.” It can’t be undone and joins such disturbing works as Death in Venice. Others painted a more sinister picture. Pastor Martin Cornils, for the Kieler Nachrichten a “Call for Censorship” wrote ominously “with ANDERS ALS DIE ANDERN, the realm of the Perverse has been entered.” More than other Aufklärungsfilme, he continued, this one sneaks in “on soft feet,” quietly endangering the social order.

Almost everyone majorly involved in this film was Jewish, with the exception of Conrad Veidt, who plays the main character, and the dancer Anita Berber. Dr. Johannes Ude, in an article entitled “Scientific Movie-trash” in the Christliche Volkswacht railed against Anders als die Andern and was particularly critical of Hirschfeld, writing “Hirschfeld is Jewish, that explains something.” For Ude, Hirschfeld is not scientifically credible, and while he does not link this assertion specifically to Hirschfeld’s Jewishness, it is implied. “Dr. Hirschfeld,” he wrote, “although he appears to be an assimilated Jew, is still in no condition to empathize with our German people in these hard times. With his scientific movie-trash, he did an extremely bad service to our German people.” Oswald mostly attracts attention for his moneymaking abilities.

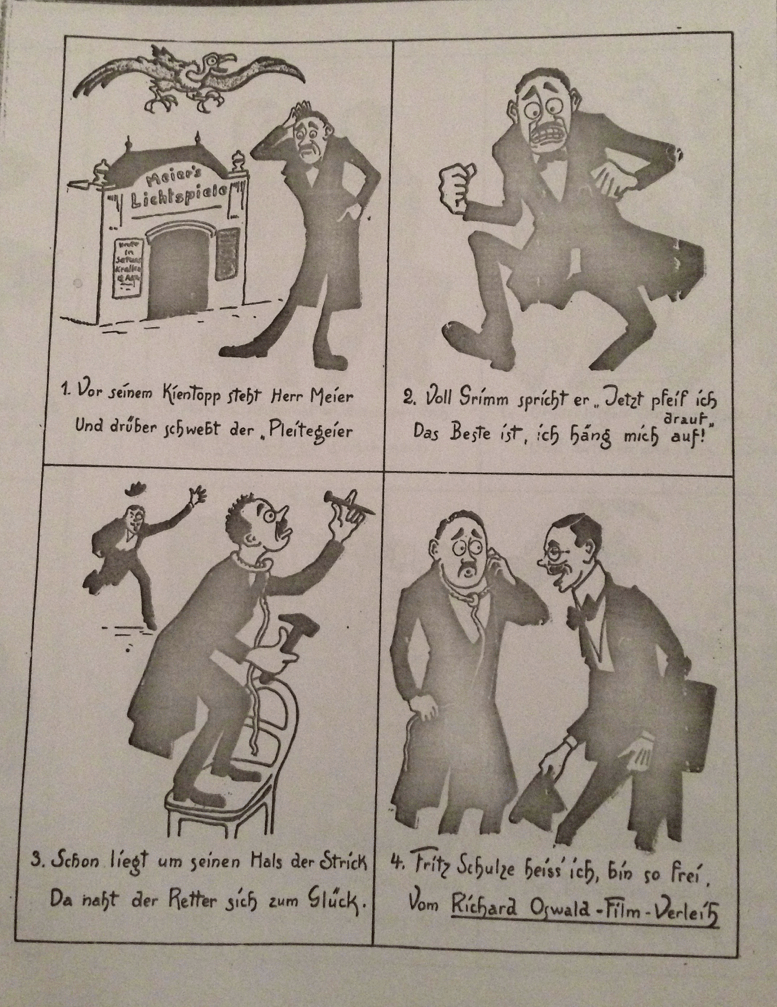

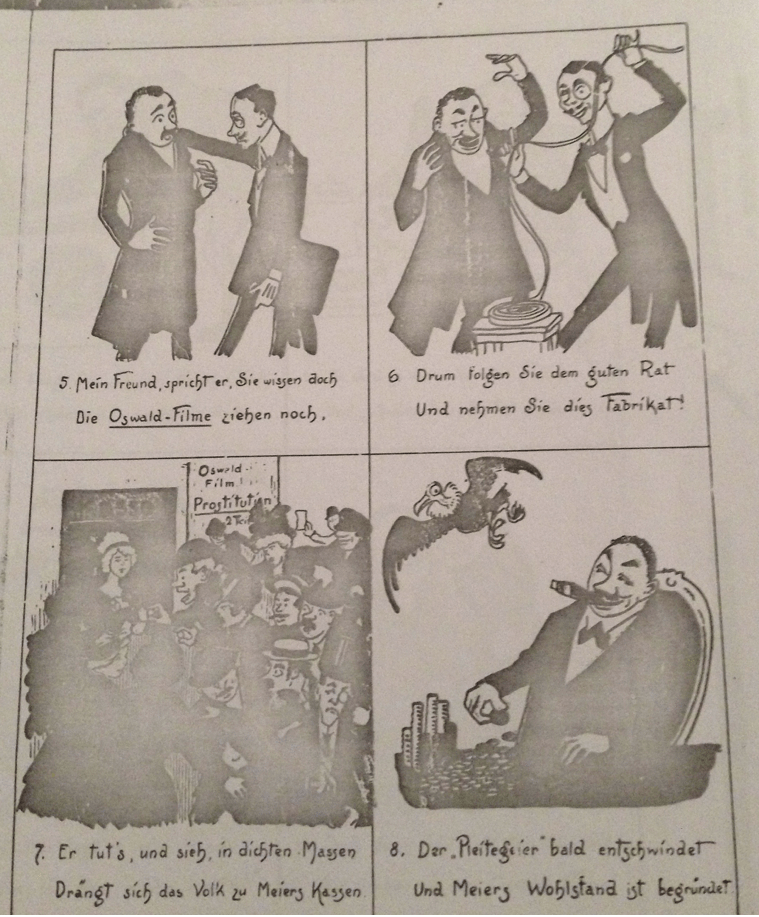

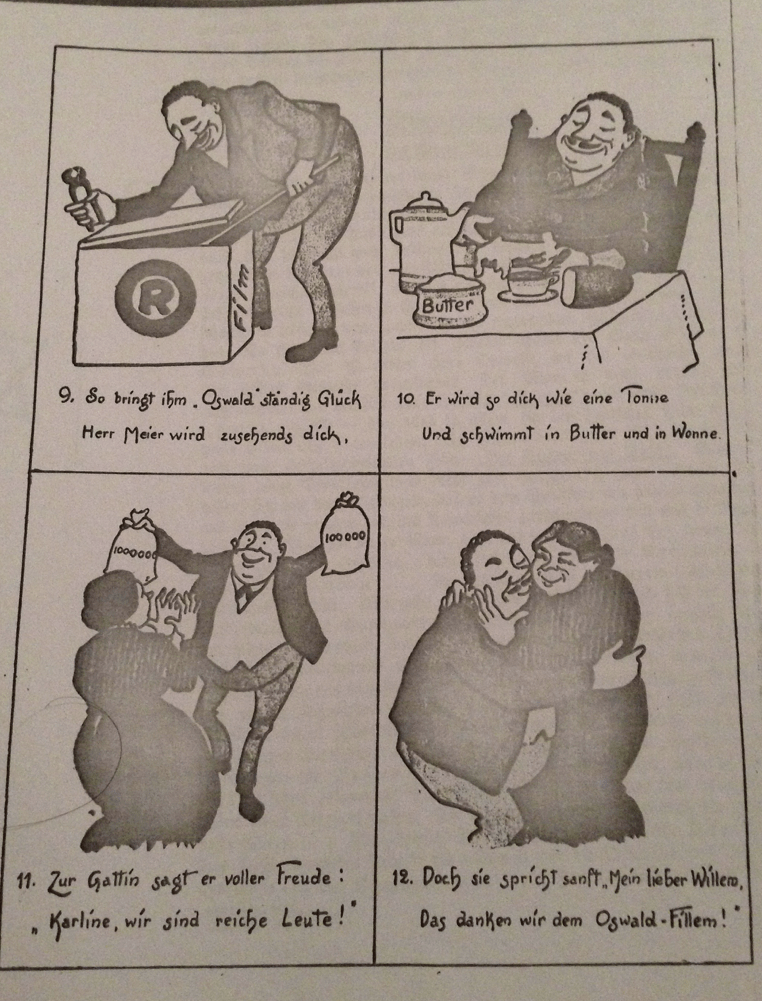

Oswald’s films were so lucrative that their profitability became its own phenomenon. Dismissing the films’ messages, commentators saw the Aufklärungsfilme as vulgar, silly indications of an enormous public appetite for smut. A humorous take in the Film-Kurier told the story of Herr Meier, a movie theater owner threatened by the bankruptcy vulture:

1.In front of his movie theater stands Herr Meier / and over him hovers the bankruptcy vulture 2. Furiously he says “Screw it / the best thing is, I’ll hang myself” 3. Already the noose was around his neck / and the rescuer luckily neared. 4. Fritz Schulze I’m called / from Richard-Oswald-Film-Verleih.

5. My friend, he says, you surely know / the Oswald films are still drawing [crowds]. 6. So follow the good advice / and take this make! 7.He does it, and look, in thick masses / the people pressed towards Meier’s ticket window. 8. The bankruptcy vulture already gone / and Meier’s wealth is established.

9.So “Oswald” brings him constant luck / Herr Meier becomes noticeably fat. 10. He becomes as fat as a ton / and swims in butter and happiness. 11. To his wife he says full of joy / “Karline, we’re rich people!” 12. But she said softly “My dear Willem” / We owe that to the Oswald-Fillem!” [From the Deutsche Kinematek archive in Berlin, issue of Film-Kurier from 18 July, 1919.]

Disappearing act

Anders als die Andern’s disappearance is well-documented. Die Freundschaft published several articles with more or less veiled accusations that critics had not seen the film. Critics argued that it was not necessary to see Anders als die Andern to find it offensive. Oswald wrote to the National Assembly accusing those favoring censorship of not having even seen the films they abhorred. These two arguments – that Anders als die Andern was so offensive it shouldn’t be seen or that it was tasteful and completely inoffensive – factored into its disappearance. The film that was supposed to jolt its audiences into compassion was repeatedly rendered harmless.

From our vantage point, Anders als die Andern makes for a strange emissary, encapsulating hopes for an imagined future from a brief window of time when that future was actually possible. The film exists now as a fifty-minute chimera, cobbled together from stills, as well as footage that survived the Nazi takeover and was found in the Soviet Union in 1970. This time around, it is easy to find on Youtube or Archive.org. Anders als die Andern becomes a “twice-told tale,” playing out at both ends of the 20th century, separated by a gap of literal disappearance. It reappeared into a world where the original antagonist, Paragraph 175, remained on the books in Germany; the law would finally be abolished in 1994 and its victims granted reparations in 2016. For us, the audience of the “second tale,” the film’s message of tolerance for sexual minorities continues to resonate on the hundredth anniversary of its premiere. In 1919, Anders als die Andern was ahead of its time; in 2019, it is ahead of ours.

Sara Friedman is a Ph.D candidate in History at the University of California, Berkeley, focusing on film and public health in Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany.

May 29, 2019 at 8:20 am

There’s an excellent book by James Steakley about the movie: “Anders als die Andern”. Ein Film und seine Geschichte. Hamburg: Männerschwarm Verlag 2007, https://www.hsozkult.de/publicationreview/id/rezbuecher-11081