By guest contributor Max Norman

On November 16th, Alain Juppé, mayor of Bordeaux, made an important announcement: the bones of Michel de Montaigne have been discovered.

Or, at least, the bones might have been discovered. “Let’s keep our cool,” said Juppé at a press conference that morning. “We haven’t yet found Montaigne. But if it were the case,” he continued, “it would be a great moment for Bordeaux.”

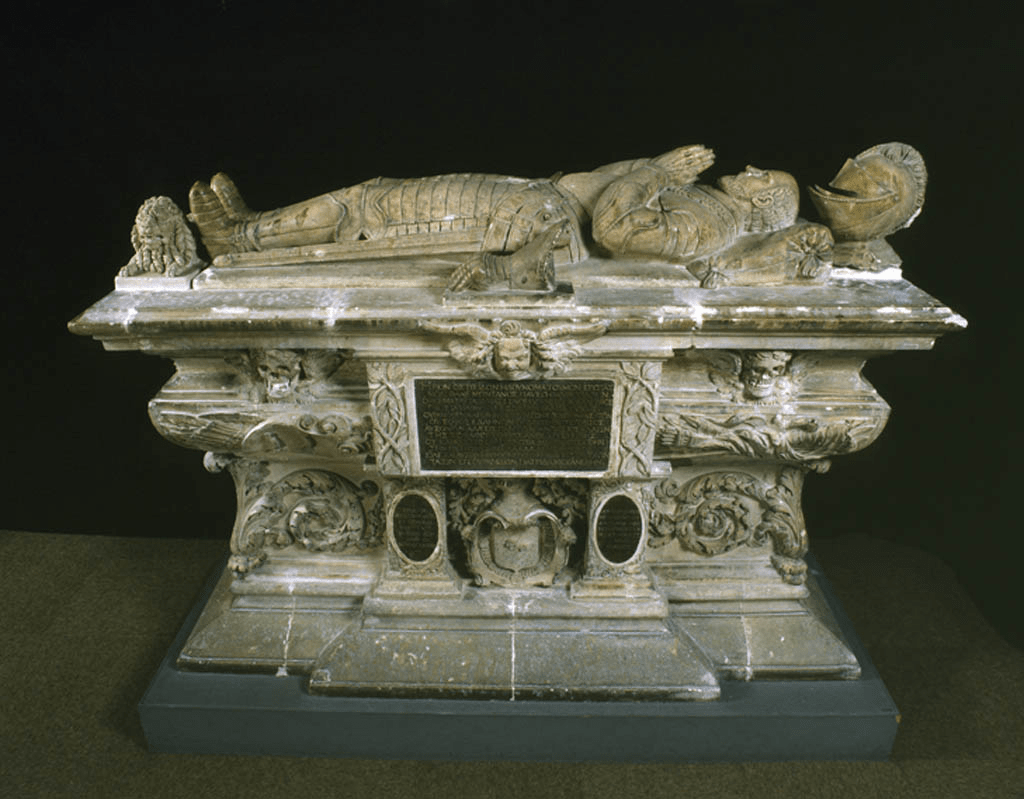

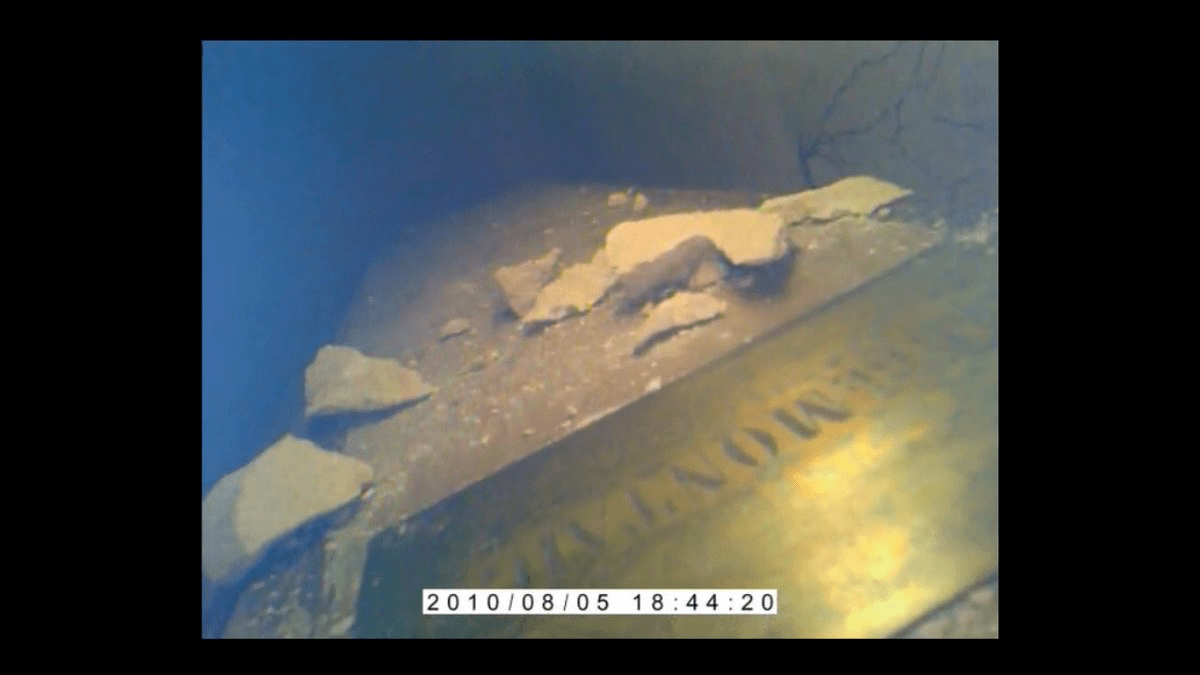

Montaigne, two-time mayor of Bordeaux, minor aristocrat, and inventor of the essay form, died in his tower in 1592, cause of death unknown. The next year the essayist was interred in a chapel on the west bank of the Garonne, the current site of the Musée d’Aquitaine. Montaigne’s cenotaph—a gaudy white marble affair—has been on more or less continuous display since it was carved in 1593. But his physical remains were lost in one of their 19thcentury translations to and from the nearby Chartreuse cemetery, for safekeeping when a fire devastated the chapel. No one seems to have looked for them until last year, when a curator at the Musée, Laurent Védrine, decided to investigate a mysterious crypt in the museum’s basement, sealed since 1886. Miniature cameras returned grainy images of a dusty wooden box, with the big black letters “MONTAIGNE” clearly visible beneath some chunks of fallen plaster. Researchers announced their intention to inventory the contents and to track down a descendant for DNA confirmation, but we’re still waiting for the results.

After the announcement, Juppé sounded a philosophical note in a mid-morning tweet: “In a world in which we speak of anger, and where we confront violence, we must return to our heritage and to the values that are dear to me [sic]. #tolerance #balance #Bordeaux.” Juppé of course knew that the Gilets jauneswould march for the first time the next day, flooding the streets of cities across the country in protest against the economic policies of Emmanuel Macron.

*

Michel de Montaigne

“C’est moy que je peins,” Montaigne writes in his opening preface “To the reader.” “It’s me that I paint.” The Essays are an intellectual portrait of one of history’s great minds, whose gentle humaneness and grinning wit are as familiar as the high forehead, ruffled collar, and thin moustache with which he is depicted in paintings and on frontispieces. But the book is also the portrait of one of history’s most average bodies, a very particular specimen that readers get to know with the intimacy of a doctor or a lover. We learn, among other things, that Montaigne didn’t like salad but was fond of melon, that he liked to ride on horseback, preferred to make love lying down, not standing up, and walked with a firm gait. This is a book, after all, “consubstantial with its author” (Villey-Saulnier edition, 665C). Finding bones, then, is almost as good as finding a manuscript.

Montaigne’s idiosyncrasies give the Essays much of their charm. They’re also one important source of what might be called Montaigne’s philosophy—a philosophy, or at least an ethics, that is rather accurately summarized by Juppé’s hashtags. “There is no quality so universal in our image of things than diversity and variety,” he writes in “On Experience,” his final essay (1065B). Human beings are simply too complicated to be theorized: “I study myself more than any other subject. It’s my metaphysics; it’s my physics” (1072B). Metaphysics and physics collapse when “every example limps”—every case is peculiar, every example is imperfect—and therefore every inference and every assumption is a kind of violence (1070C).

Even literary interpretation is risky, particularly when books are, like Montaigne’s, “members” of a life, and memorials to it. Montaigne learned this the hard way from the fate of Etienne de la Boétie, the friend of the famous essay “On friendship.” de la Boétie’s Discourse on Voluntary Slavery praised republican Venice and critiqued monarchy, arguing that, since people willingly grant a tyrant power, people can willingly take it away. The treatise was naturally appropriated by anti-monarchists in the Wars of Religion. But this was a misreading, Montaigne claims: if you knew de la Boétie like he did, you’d see that there was never a better subject, “nor a greater opponent of the disturbances and innovations of his time” (194A). If de la Boétie had written his own Essays, you would never have so misunderstood him. It’s possible, of course, that Montaigne himself was the one willfully misreading de la Boétie. Either way, his polemical interpretation reminds us that we should never entirely trust the fiction of artlessness that the essayist so often affects.

As he got older, Montaigne seemed to realize that his skepticism was, like de la Boétie’s Discourse, potentially dangerous, so in the Essays “I leave nothing to be desired or guessed about me” (“On Vanity,” 983B). Exhaustive self-description is not only a means to self-knowledge or literary immortality. It’s also an insurance policy: The flood of Montaigne’s words will overwhelm reductive misreadings with their sheer copiousness, as indeed the sheer size and labyrinthine complexity of the Essayshave defied all critical attempts at a unified interpretation. Eschewing systematic argument or organization, Montaigne prevents us from using his book, though we may profit from it. Just as we will never know if Montaigne’s representation of de la Boétie—grounded, he tells us, on intimate knowledge that is inaccessible to readers—was accurate, so we will never know for certain just what the Essays are supposed to mean, just what Montaigne is about. And that’s the point: the Essays, like the person who wrote them, ultimately prove to be something of a black box. “What I can’t represent, I point to with my finger,” he writes (983B). In the end, the Essays do no more and no less than point to their author, that infinitely peculiar human being, who, even with all the ink the world, could never be fully incorporated into his book.

*

Readers tend to remember Montaigne as individualist,as pioneer of a certain kind of Renaissance egoism. But in the final sighs of the Essays, Montaigne concludes that “the most beautiful lives to my mind are those which hew to the common human pattern, orderly, but without miracles or eccentricity” (1116B/C). When things are this complicated, the best policy is to mind your own business. Don’t assume you know better than anyone else (a lesson for Macron, who has publicly proclaimed that the French people never meant to kill their king)—and (for the Gilets jaunes) don’t try to rock the boat. Think of politics in human terms. Read your opponents charitably. Most of all, don’t be cruel.

The newly discovered box, like the cenotaph, may be empty. Part of me hopes that it is, and that readers have to keep searching for Montaigne’s bones in the Essays, reading them quite literally as a portrait, a vivid depiction of a “you” en chair et en os, in flesh and bone. This fleshly Montaigne has all too often been replaced in memory and imagination by a Montaigne made only of words. But you can’t separate the body from the book.

Max Norman studies literature at the University of Oxford.

[mc4wp_form id=”12317″]