By guest contributor, Jake Newcomb

Last year, philosopher Graham Priest published an article in the Journal of the American Philosophical Association titled “Marxism and Buddhism: Not Such Strange Bedfellows.” In the article, Priest aimed to highlight the complementary elements of Buddhist philosophy with Marxist political theory, while acknowledging that, as schools of thought, these two ways of looking at the world diverge drastically. The crucial similarity between the two, Priest rightly points out, is the fact that both schools “reject the existence of a self/soul; both see being human as being involved in natural processes and natural laws; and both move toward thinking of people in mostly structural terms,” (Priest 7). They also, according to Priest, both make the argument that people are subjected to illusions about the true nature of reality, and provide a framework by which people can see these illusions. Priest suggests that the structural analysis of capitalism provided by Marxism can help to elucidate the philosophy of the human condition presented by Buddhism, and vice versa. A comparative analysis along these lines appears to be possible, and there has been a long tradition of comparing Marxism to religion. The following essay will be a brief history of the relationship between Marxism and religion. It will attempt to highlight, through Hegelian philosophy, another similarity between Marxism and Buddhism, as well as describe the relationship between Marxism and Christianity.

The keystone which links Marxism to Buddhist philosophy is Hegel. Hegel’s conception of reality, as a series of dialectically intertwined processes, was reinterpreted by Marx and Engels as a framework by which all of reality could be explained without theology. The important element here is that these men believed that all the things and processes that make up reality could not be understood in isolation, but only in relation to other things and processes. Hence, in Hegel’s Logic, the very mention of “Being” implies the existence of “Nothing,” (Hegel, Logic, 82) This fundamental inseparability of objects and processes appears to be the primary way in which Marxist thought, which was inspired by Hegel, is similar to the Buddhist thought that Priest presents. In fact, the philosopher Michael Allen Fox’s book The Accessible Hegel presents the Hegelian dialectical framework as sharing this same fundamental quality with not just Buddhist conceptions of reality, but Taoist ones as well. Both of which, Fox argues, present reality as being a collection of interrelated processes, by which nothing can be understood in isolation. Fox says that “the idea that opposites are interrelated and define one another, as we have seen, conveys an insight that is truly cross-cultural,” because of its appearance in Hegelian, Buddhist, and Taoist thinking (Fox 48).

Despite this apparent connection between his philosophical framework with Buddhism, and Taoism, Hegel argued that Christianity was the highest expression of religious truth in Phenomenology of Spirit (Fox 99-100). According to Fox, Hegel wanted to merge Christianity with the belief the reason governs the development of the universe, although this caused major backlash from non-Christians and Christians alike such as Marx and Kierkegaard (Fox 100). Hegel was not unaware of the existence of philosophical frameworks from Asia. In fact, in Reason in History, Hegel suggested that the “highest thought” of the metaphysics that came from Asia rested in their proposition that “ruin is at the same time emergence of a new life, that out of life arises death, but out of death life,” (Hegel, Reason in History, 88) However, despite this acknowledgement, Hegel argued that the religions of China and India “lack completely the essential consciousness of the concept of freedom,” which, he argued, was what separated these philosophies from those of Europe (Hegel, Reason in History, 86) Today, we consider this to be regarded as an expression of orientalism, à la Edward Said. But it’s important because it denotes the limits of what Hegel and his contemporaries could appreciate from systems such as Buddhism. According to Nicholas A. Germana in a recently published article in the Journal of the History of Ideas, Hegel believed the religions of India and Asia morphed into Christianity over time.

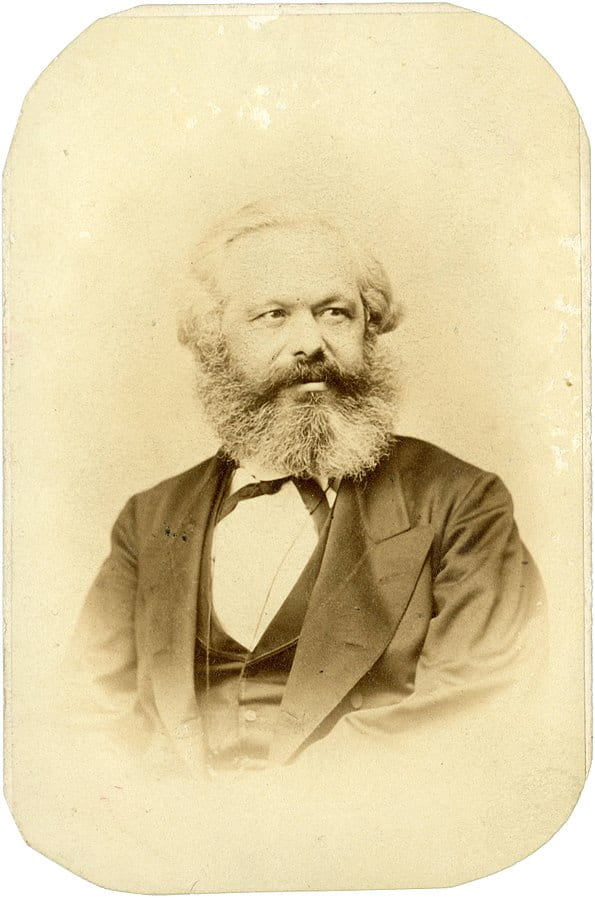

It was Hegel’s support of Christianity that Marx first took issue with in Hegel’s schema, which he himself was heavily influenced by. In 1844, Marx published Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. In the introduction, Marx wrote the now famous line, “[r]eligion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the sentiment of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people,” (Tucker 54). Here, as elsewhere in this essay, Marx is clear in what he believed to be religion’s function in human society: a human-constructed refuge from the suffering of life. A few lines down from this oft-repeated quote is a fundamental claim made by Marx which helps contextualize his later work:

“The immediate task of philosophy, which is in the service of history, is to unmask human self-alienation in its secular form now that it has been unmasked in its sacred form. Thus the criticism of heaven is transformed into the criticism of earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics.” (Tucker 54)

The self-alienation in its “secular form” that Marx claimed existed, appears as the form of commodity fetishism in Capital Vol. 1, published in 1867. Here, Marx argued that the pricing of commodities depended on the total aggregate relationships between people, and not the utility of the object itself (Marx, Capital, 165). This reality, according to Marx, tricks people into thinking that commodities have an autonomous value, independent of the sum of human relationships. An illusion of the mind which Marx liked to the illusions of reality brought upon by theology. Capital, as a project, was an attempt to demystify the pricing of commodities and the capitalist system of production as a whole, in a similar fashion to the deconstruction of Christianity that he participated in during the 1840s. The mystification of capital, for Marx, created alienation in people in the way that he argued Christian theology did. In Marx’s world, capitalism and Christianity were not so strange bedfellows (Marx, Capital, 174-175).

But, as numerous scholars have pointed out, Marx and further proponents of Marxism carried on the legacies of Christianity in several respects. William Clare Roberts, for instance, argues in Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital that Marx based the structure of Capital on Dante’s Divine Comedy, specifically Inferno. Even though Marx rejected the Christian moral ontology, espoused by Dante, that “[n]o one is responsible for their sins but themselves,” Roberts argues that he replicated the structure of Inferno in order to liken capitalist society to a social hell (Roberts, Marx’s Inferno, 21). Then there is Bertrand Russell, who in 1946 published History of Western Philosophy which clearly cast Marxism as a secularized substitute for the Judeo-Christian understanding of history. Russell argued that Marxism simply cast the theological understandings of history’s teleological trajectory in new terminology:

“Yahweh = Dialectical Materialism

The Messiah = Marx

The Elect = The Proletariat

The Church = The Communist Party

The Second Coming = The Revolution

Hell = Punishment For The Capitalists

The Millenium = The Communist Commonwealth”

(Russell 338)

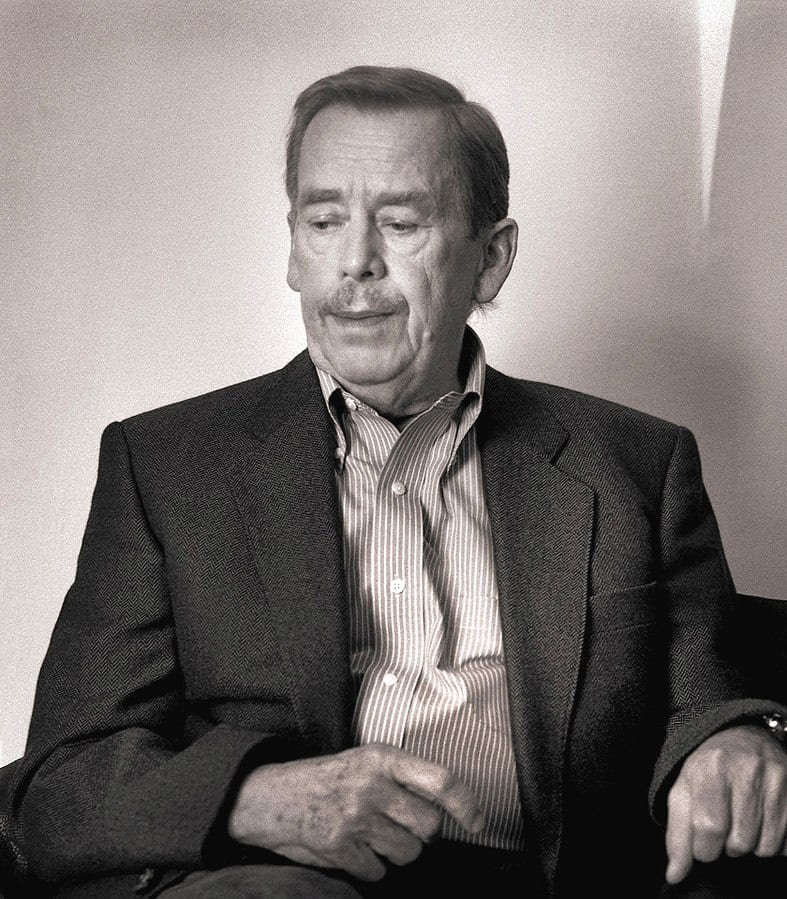

It stands to reason that Russell’s typecasting of Marxism as a new form of Christianity was influenced by the rise of the Soviet Union. Vaclav Havel, the last President of Czechoslovakia who presided over the collapse of the Soviet system, also likened the practical application of Marxism to a modern form of theocracy. In his masterful 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless,” Havel argued that the “hypnotic charm” of the Soviet ideology was due, in part, by its insistence that its legitimacy derived from the authenticity of the social movements that gave birth to the system, and the supposed objective righteousness of those movements (Havel, Open Letters, 129). This created a situation whereby ordinary people within the communist world, including Czechoslovakia, consigned “reason and conscious” to the state, who were the sole possessors and arbiters of truth. Which, for Havel, directly reflected a Byzantine-esque theocracy because the “highest secular authority [the state] is identical with the highest spiritual authority,” by having authoritarian control over truth and a claim to a sacred history (Havel, Open Letters, 130). These works indicate in differing ways the extent by which Marxism, in Marx’s Capital and in twentieth-century communist practices, bore resemblances to Christianity.

It stands to reason that Russell’s typecasting of Marxism as a new form of Christianity was influenced by the rise of the Soviet Union. Vaclav Havel, the last President of Czechoslovakia who presided over the collapse of the Soviet system, also likened the practical application of Marxism to a modern form of theocracy. In his masterful 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless,” Havel argued that the “hypnotic charm” of the Soviet ideology was due, in part, by its insistence that its legitimacy derived from the authenticity of the social movements that gave birth to the system, and the supposed objective righteousness of those movements (Havel, Open Letters, 129). This created a situation whereby ordinary people within the communist world, including Czechoslovakia, consigned “reason and conscious” to the state, who were the sole possessors and arbiters of truth. Which, for Havel, directly reflected a Byzantine-esque theocracy because the “highest secular authority [the state] is identical with the highest spiritual authority,” by having authoritarian control over truth and a claim to a sacred history (Havel, Open Letters, 130). These works indicate in differing ways the extent by which Marxism, in Marx’s Capital and in twentieth-century communist practices, bore resemblances to Christianity.

It is thus clear that there is sufficient cause to acknowledge similarities between Christianity and Marxism. Today, in the twenty-first century, there is a striking trend in Christianity that is adopting political positions that would be considered Marxist not so long ago. This is expressed most potently in Pope Francis’s Encyclical on Climate Change & Inequality: On Care for Our Common Home in which he argues that wealth inequality, climate change, and the loss of biodiversity are interconnected with the rise of global capitalism. Pope Francis considers this to be an issue that transcended national boundaries, and he advocates on global cooperation in order to adjust our value-systems in order to move toward ecological balance and wealth equality. Graham Priest forces us to recognize that there is a deep philosophical relationship between Marxism and Buddhism as well. These similarities are very different from the aforementioned similarities between Marxism and Christianity, but both sets of similarities invite us to reconsider the history of Marxism itself. Marxism has often been understood as an atheist political ideology, whose practitioners took drastic measures to curtail the influence of Christianity and Buddhism. But the work of Priest, Russel, and Havel beg the question: to what extent was Marxism a religion?

Jake Newcomb is an MA student in the Rutgers History Department, and a musician. His essays on his personal experience with music can be found at jakenewcomb.tumblr.com

[mc4wp_form id=”12317″]

June 5, 2019 at 9:08 am

I didnt know economics had something to do with being a Buddhist