[mc4wp_form id=”12317″]

By contributing editor Jonathon Catlin and guest contributor Lotte Houwink ten Cate

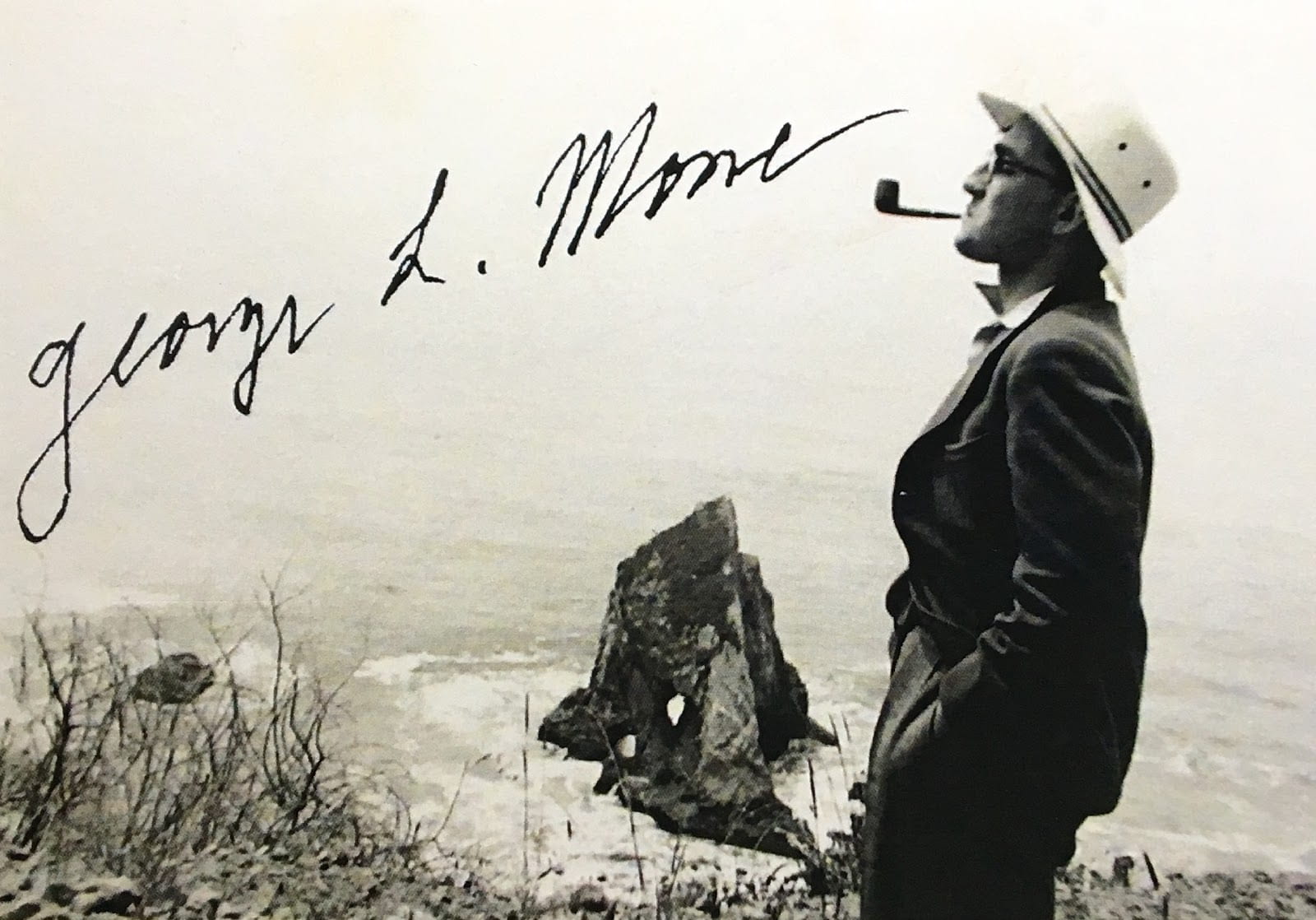

From June 6–9, 2019, over thirty eminent scholars of German and Jewish history and culture gathered in Berlin at the conference “Mosse’s Europe: New Perspectives in the Study of German Judaism, Fascism, and Sexuality” to critically reassess and carry on the legacy of the pathbreaking German-Jewish historian George L. Mosse (1918–1999) on the occasion of the centenary of his birth. Presentations concerned both Mosse himself, including reminiscences from the many students he trained during his long career, and also new research inspired by his more than two dozen books. Of particular importance is new work about women, queer history, and the study of sexual violence that complements Mosse’s earlier work on masculinity and male sexuality.

The conference began with the remarkable story of Mosse’s family, who owned and published the Berliner Tageblatt, a leading liberal newspaper that has been called the New York Times of Weimar Germany. They lived in magnificent estates in Berlin and the neighboring countryside, and young George enjoyed an idyllic bourgeois childhood. However, the family’s fortune was not without its costs. Roger Strauch, Mosse’s great nephew, remarked that Mosse’s grandfather, the tycoon Rudolf Mosse, was “the George Soros of his day,” as Hitler and Goebbles often invoked the Mosse name to stoke myths of Jewish power and conspiracy. Despite the pressure of antisemitism, it seems, remarkably, that no Mosses converted to Christianity. Meike Hoffman also noted a decisive error in the biography of the family by Elisabeth Kraus: The Tageblatt was declared bankrupt on 19 September 1933—and not 1932, as Nazi documents claimed; hence the newspaper was not sold or handed over willingly to an “Aryan” owner, but rather seized under the fictitious pretense of bankruptcy.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, when George was fifteen, his family fled to France, Switzerland, and then America. He attended a Quaker boarding school in England, then Cambridge and Haverford College, and earned a Ph.D. in history from Harvard in 1946. Mosse began his scholarly career as a specialist on English constitutional history of the 16th and 17th centuries. By 1955 he moved to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he began teaching the modern German and Jewish history that had profoundly shaped his own life. As he concluded his memoir in 1999:

“The Holocaust was never very far from my mind; I could easily have perished with my fellow Jews. I suppose that I am a member of the Holocaust generation and have constantly tried to understand an event too monstrous to contemplate. All my studies in the history of racism and volkish thought, and also those dealing with outsiderdom and stereotypes, though sometimes not directly related to the Holocaust, have tried to find the answer to how it could have happened; finding an explanation has been vital not only for the understanding of modern history, but also for my own peace of mind. This is a question my generation had to face, and eventually I felt I had come closer to an understanding of the Holocaust as a historical phenomenon. We have to live with an undertone of horror in spite of the sort of advances that made it so much easier for me to accept my own nature…. The issues of the Third Reich were writ large in my consciousness, a part of my personal transformation from the irresponsibility of youth, a past which had to be faced. I had rejected the worlds of my past and had sought to transform myself, but in my anxieties, fears, and restlessness, I was still a child of my century.” (Confronting History: A Memoir, p. 219)

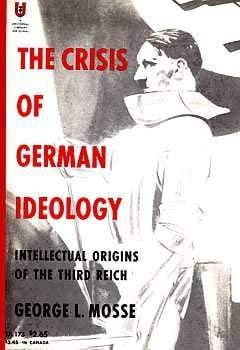

In order to understand European fascism, his former student Steven Aschheim (Hebrew University) said, Mosse “de-ghettoized” Jewish experience. He pioneered a unique cultural approach that broke out of the essentialist and closed practice of Jewish history he encountered in Israel. Hence, for example, Mosse’s classic The Crisis of German Ideology: The Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (1964) describes the rise of Nazism not only as an “anti-Jewish revolution” but also as a broader “spiritual revolution” that drew upon and weaponized older volkish ideas and other forms of racism.

In his four decades at Wisconsin, Mosse trained dozens of graduate students until his retirement in 1987. As an entertaining graphic novel about his life illustrates, Mosse resisted the radicalization of the campus in the 1960s, proudly asserting to his students: “This course is designed to rid you of your slogans.” The mob of student activists apparently stood in violation of his dictum, “let us be wary of forced conformity,” or, as Aschheim put it, “beware of normalcy.”

Beginning in 1969, Mosse spent a semester each year teaching at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, several Mosse family properties appropriated by the Nazi state and then East Germany were restituted to Mosse. Upon his death in 1999, he donated the restitution to the University of Wisconsin–Madison (whose unsightly humanities building still bears his name), home to the Mosse Program, which facilitates scholarly exchanges between Wisconsin and Hebrew University and also sponsors annual lectures in Madison, Jerusalem, and Berlin. Collaborative efforts to restitute the family’s art collection are ongoing at the Freie Universität Berlin.

Alongside historians such as Peter Gay, Carl Schorske, Fritz Stern, Walter Laqueur, Arno Mayer, Raul Hilberg, and Saul Friedländer, Mosse was part of an intellectual cohort recently considered together in The Second Generation: Émigrés from Nazi Germany as Historians (2015). While others shared Mosse’s turn to cultural history, Mosse’s open homosexuality helped lead him to original insights about the centrality of sexuality and masculinity to nationalism. On this front, Kilian Harrer has written a fascinating piece about Mosse’s missed encounter with Foucault. While Mosse’s published writings are generally dismissive of the more radical French theorist, he read Foucault with great interest. Mosse wrote in the margins of his copy of Histoire de la sexualité: La volonté de savoir (1976): “Yes, sex part not of traditional legal power but of symbolism and myth of new politics.” He explored such ideas further in his late reflections on homosexuality, such as “Why Gay History?” (1996).

In opposition to many German historians who fled from politics into the social history of structure and bureaucracy, Mosse saw fascism as a cultural totality that satisfied the need for “a fully furnished house” of normative order and a sense of stability (George L. Mosse’s Italy, p. 42). Fascism offered a new vision of man, a dynamic worldview, a secular “liturgy” for the politicized masses. Mosse wrote in his memoir that he was by no means above these longings himself: he found certain currents of Zionism seductive and was awed by the spectacle of a Hitler rally as a teenager. As Aschheim noted, in order to understand fascism, Mosse studied its internal self-representations, exploring such “irrational” topics as its obsessions with gymnastics, the “Jewish nose,” and “degenerate” masturbation.

As Darcy Buerkle (Smith College) noted, Mosse called Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectability and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe (1985) his “coming out book.” This book has been described by his former student Anson Rabinbach (Princeton) as “a path-breaking study of how stereotypes like ‘healthy’ and ‘degenerate’ and ‘normal and abnormal’ underlay what became the persecution of Europe’s Jews, homosexuals, Gypsies and the insane.” As Aleida Assmann (Konstanz) noted, for Mosse, the “heil und gesund” (well and healthy) national body invented outsiders as a moral yardstick against which to assert its own respectability. Ideal types exist in a dialectic with anti-types. The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity (1998) further expanded the way the figures of the feminized Jew and homosexual figured as “others” to the bourgeois ideal of “the soldierly man.”

Mosse’s work defied conventional periodization by highlighting cultural continuities across historical caesuras. For example, he argued that Nazism simultaneously embodied and transcended earlier notions of bourgeois respectability. Assmann credited his attention to everyday habits, symbols, and rituals as influential for her own field of memory studies. Mosse’s late work argued that memory regimes including the “cult of the fallen soldier” and the “myth of the war experience” after the First World War led to “the brutalization of German politics” and paved the way for another war. Assmann, in turn, explores the gulf between horror and glory at the Second World War in national memories.

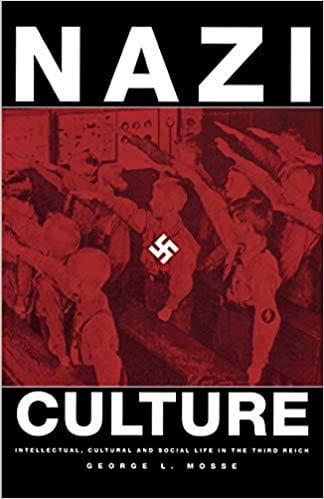

When Mosse’s anthology Nazi Culture: Intellectual, Cultural, and Social Life in the Third Reich appeared in 1966, this title was widely considered a contradiction in terms. Mosse insisted that one could only understand the Nazi regime from within its own framework of meaning. His many students, many of whom co-organized the conference, carried this insight further: Jeffrey Herf’s (Maryland) Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (1984) argued that Nazism was a modernism. Steven Aschheim illustrated the centrality of crisis, exile, and the “othered” figure of the Eastern European Jew in the German-Jewish imaginary. Anson Rabinbach developed a Marxist theory of fascism as a “cultural synthesis” and explored obsession with the masculine ideal of the energetic laboring body. Together with Jack Zipes and David Bathrick, Rabinbach co-founded New German Critique in Madison in 1973 amidst the intellectually rich and politically engaged community Mosse helped to foster in this liberal Midwestern oasis.

Amidst a sea of entertaining stories from former students about Mosse’s at times “outrageous” and pompous character, co-organizer Atina Grossman reflected upon why she chose not to study with Mosse: she was warned of his dismissive attitude toward women and the nascent field of women’s history. Given her interest in gender, she opted to study at Rutgers instead.

The most original work presented concerned the history of gender and sexuality. Stefanie Schüler-Springorum (Berlin Center for Research on Antisemitism) presented on the Nazi notion of “race defilement,” which entangled desire, fear, disgust, and sexual violence in what she called “pornographic antisemitism,” while Elissa Mailänder (Sciences Po) explored sexual violence against female concentration camp guards. Mary Louise Roberts (Wisconsin) presented a comparative study of the shifting significance of rape by American GIs in Britain and France, whereas Regina Mühlhäuser (Hamburg Institute for Social Research) analyzed the framing of rape as a weapon of war not as a “terminus technicus” but as an argumentative topos. Anna Hájková (Warwick) highlighted erased queer desires and same-sex experiences among victims of Nazi persecution. As Grossmann acknowledged, these presentations were spaced out in order to avoid all-male panels. While this commendable decision did lead to missed conversations among the presenters, discussion was hindered more because of a constant lack of time.

One panel reflected on the relevance of Mosse’s work on fascism today amidst resurgent right-wing populism. Mary Nolan (NYU) explored right-wing appeals to women in France and Germany, while Andreas Huyssen (Columbia) debunked the boogeyman of Jewish “cultural Marxism” on the contemporary right. Enzo Traverso (Cornell) drew careful lines of analogy between the 1930s and today, but argued, as per his recent The New Faces of Fascism, that contemporary rightwing movements draw upon historical fascism but are ultimately “post-fascist.” Traverso also skeptically noted several distinctive elements of Mosse’s account of fascism, especially compared to the theory of one of Mosse’s closest scholarly interlocutors, Emilio Gentile. Mosse saw both fascism and Jacobinism as mass “political religions,” and hence as reactionary and counter-revolutionary elements split off from the emancipatory Enlightenment tradition that spawned the French Revolution. Rabinbach also noted that Mosse refused to separate Italian Fascism, rooted in the state, from Nazism, rooted in racial ideology. Mosse’s expansive theory of fascism also included Francoism in Spain but paid less attention to anti-fascism, the mobilizing creed of the generation that resisted it in the Spanish Civil War. Despite the subtitle of his Toward the Final Solution: A History of European Racism (1978), Mosse also paid far less attention to the earlier atrocities of European colonialism than his fellow émigré Hannah Arendt.

The final day, current and former Mosse Fellows departed from the panegyrics of the older generation and presented new directions in a variety of fields. David Harrisville (Furman) presented new work on the role of ideology in the Wehrmacht based on his analysis of a large trove of correspondence by soldiers. Arie Dubnov (George Washington) applied Mosse’s notion of the cult of the fallen soldier to Israel, which as a young nation reburied many early Zionist leaders on Mount Herzl—its Pantheon—and created new holidays and liturgies to honor fallen soldiers in Israeli wars. Ethan Katz (Berkeley) gave a fascinating preview of his new work on the role of the Jewish insurgency in Algiers and its decisive contribution to Operation Torch, extending his previous scholarship on Jewish-Muslim relations and colonialism into the field of Holocaust Studies.

Mosse is well known for his most personal scholarly book German Jews Beyond Judaism (1985), which Aschheim called “almost a confession of faith.” This work has been interpreted in Mosse’s Festschrift as a response to Gershom Scholem’s polemical denunciation of “the myth of the German-Jewish dialogue.” Former Mosse student David Sorkin (Yale) added that with this work Mosse aimed to highlight secular forms of Jewish culture beyond Zionism. Mosse emphasized the centrality of the German notion of Bildung (cultivation) in German-Jewish experience. He called it “the knighthood of modernity” and described it as a means of cultural redemption and a “secular religion” particularly important to Jews, such as his own family, who had given up traditional faith. The Germanocentrism and elitism of this thesis has received ample criticism from such scholars as Aschheim, Peter Jelavich, and Shulamit Volkov. Yet the ideal of Bildung continued to shape Mosse’s thinking and way of life well after his departure for the United States, informing his humanism and what Herf called his “Cold War liberal” politics.

On the final day, Herf claimed that not enough attention had been paid to antisemitism, apparently overlooking the persuasive arguments that had been made about its intersections with gender and sexuality (about which, according to Herf, “much had been said”). Herf took issue with Mosse’s view of the Sonderweg thesis of German’s path to the Holocaust for being “too short term” (though he walked back his Sonderweg position in later editions of The Crisis of German Ideology) and drew similarities between the fascist revolutions of the 1930s and “the global Jihad” today. As Ethan Katz (Berkeley) responded, Mosse’s work can be a source for thinking about antisemitism alongside other forms of othering, not least the current wave of anti-Islamic sentiments in academia.

These issues simmered just below the surface of Aleida Assmann’s concluding keynote, entitled “Mosse’s Europe: Can it be Saved?” Her talk at Berlin’s Jewish Museum was introduced by the museum’s then director, Peter Schäfer, a legendary scholar of Jewish history who recently resigned following a controversy over a tweet from the museum that linked to a letter signed by 240 Jewish studies scholars who oppose recent German legislation that conflates support for the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel with antisemitism. In such recurrent debates about the limits of acceptable discourse, academic freedom, and the place of politics in Jewish museums, the specter of the Nazi past continues to haunt postwar Germany.

Assmann returned to Mosse’s work as a resource for understanding nationalism today. She invoked his “outsiderdom” as a self-described “eternal emigrant,” a gay man, and a Jew, who saw his own German-Jewish Bildung as “building a dam of scholarly and intellectual authority against the flood that is threatening to drown all educated and rational minds.” He saw antisemitism as the core of the National Socialist state and described racism as its “secular religion.” Yet he also experienced antisemitism in the United States through exclusion from universities and clubs. Nazi Germany became Mosse’s principal historical case, but it was only one crucible of dark currents of othering that continue to pervade Western culture.

In her concluding words, Assmann turned to a side of Mosse few others addressed. In his youth, Mosse developed an affinity for socialism. As an adult this moderated into support for the social-democratic welfare state, but he maintained criticism of “uncontrolled capitalism.” Some of Mosse’s reflections on this front, Assmann suggested, speak directly to challenges faced in our contemporary political moment: “We are getting more and more accustomed to homeless people, as though this was quite a natural state of being. The rough tone in dealing with those who have suffered social damage has not at all changed. That people are no longer trying to alleviate these problems—that they are taking this for granted—this is a new development. This is a new phenomenon of the 1980s. The real outsiders are those who are damaged by this system.” The rich historical imagination of Mosse’s work may prove an essential resource as we find ourselves pressed to reimagine society and the nation today.

The conference papers will appear in a forthcoming volume in the George L. Mosse Series in Modern European Cultural and Intellectual History published by the University of Wisconsin Press.

Jonathon Catlin is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at Princeton University. His dissertation in progress is a conceptual history of “catastrophe” in modern European thought, focusing on German-Jewish intellectuals including the Frankfurt School of critical theory.

Lotte Houwink ten Cate is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at Columbia University, and a Visiting Fellow at the Freie Universität in Berlin. Her dissertation is an intellectual history of the classifying and criminalizing of domestic and sexual violence across western Europe since 1970.

July 28, 2019 at 5:11 am

If he was still alive, Robert Pois would have loved this gathering. Thanks for putting this together.