By Luna Sarti

Something that always surprises me in the perception of river flooding is how we tend to reduce different floods to recurring iterations of the same phenomenon. Historical river floods are in fact usually evoked by means of the year in which they occurred and in relation to the most noticeable urban area that they affected. On one hand, this way to refer to different floods standardizes each event and effectively erases the heterogeneous causes that contribute to their occurrence. On the other hand, the ‘by-year-label’ allows a low degree of difference which is functional to comparatively measure the magnitude of devastation that each iteration causes. This way of thinking about floods contributes to divert the discussion of how and why each flood takes place towards a more “sensational” narrative, which is typical of “disaster culture” (Robert C. Bell and Robert M. Ficociello). Is a flood just a flood among others? Shouldn’t we learn to reflect on each flood separately?

The Trinity River in the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex provides an interesting case for a reflection on river floods. Between 1908 and 1949, in fact, following the occurrence of increasingly severe flooding events, local authorities created a system of levees that will soon be dismantled. According to the Trinity River Vision Authority, in fact, the current levee system is not only inadequate for contemporary flood risk, but prevents the development of river ecology as well as direct access to the river. Launched in 2002 and supervised by the Trinity River Vision Authority, the Trinity River Vision Project promises flood damage reduction, ecological renewal, and opportunities for recreation and development. The project advocates for the Renaissance of local river culture and draws on a “holistic approach to flood protection” in order to safeguard Fort Worth and transform it into a riverfront city.

The language of the Master Plan prompts a certain level of risk, that of flooding, and at the same time provides us with a well-designed solution that guarantees safety while enhancing beauty. It enables a positive vision of the future that capitalizes on fears of loss caused by uncontrollable events as well as on the feeling of awe that providential technology can inspire. The reference to the theme of “renaissance” seems not coincidental in that in its “holistic” vision the project advocates for a beautified city which redirects the community towards the river as a source for pleasure, entertainment, and relief. Much could be said on this reference. However, what concerns me here is that the Trinity River Vision Authority capitalizes on the tension between an enhanced sense of flood risk and an already-made providential solution without providing an adequate contextualization of flooding.

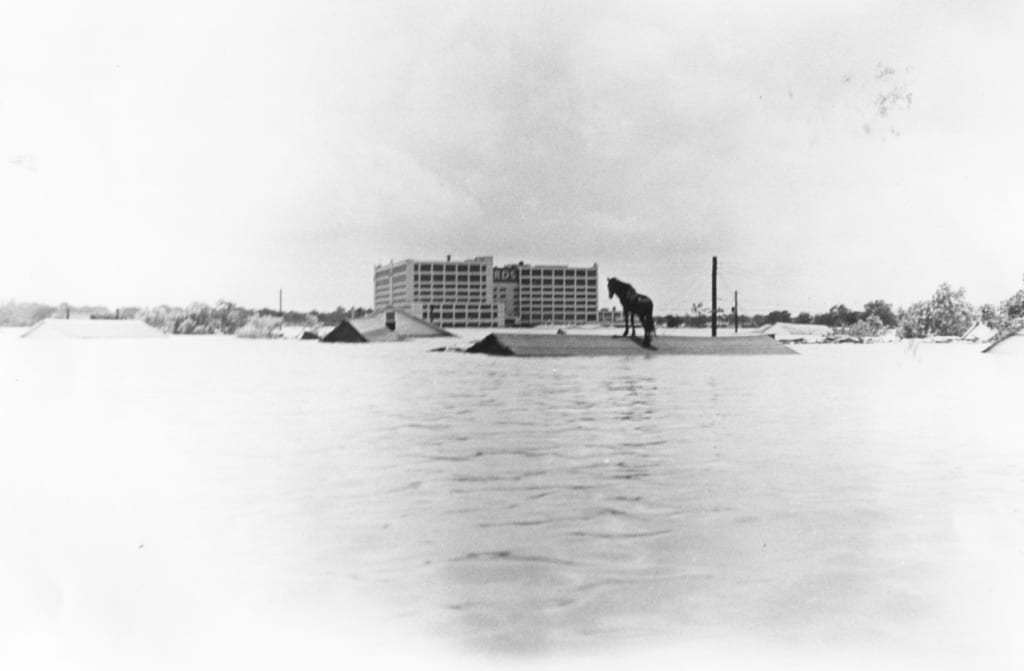

Located at the junction of Clear Fork and West Fork of the Trinity River, Fort Worth has experienced several episodes of extreme flooding, most noticeably in 1844, 1866, 1871, 1890, 1908, 1922, 1949 and 1989, while flash flooding is a frequent occurrence. The Plan only includes an introductory remark on the 1949 flood as “a massive flood” that “destroyed much of the city” and continues with “the river reached a depth of 52 feet and a width of 1.5 miles, killing 10 people and leaving 4,000 citizens homeless” (9). However, the Report on Trinity River at Dallas and Fort Worth, presented by the Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors on March 11, 1949 provides us with a much more complex scenario for understanding the occurrence of that “massive” flood (Committee on Public Works; id: 11324 H.doc.242). According to the document prepared by the Board of Engineers on March 11, 1949, in fact, the population of Dallas had increased from 295,000 in 1940 to 483,000 at the time, and of Fort Worth from 178,000 to 318,000 (5). The Board of Engineers connected flood risk to this “extraordinary growth” which “accelerated development and utilization of the reclaimed flood-plain lands at both cities for residential, commercial, and industrial purposes” (6). Drainage is thus identified as a significant issue, because existing infrastructures did not seem to be able to sustain both discharge and storm waters. Such a historical reflection allows a more refined understanding of the elements that produce flooding, which is less about nature and devastation, and more about policy and social behaviors.

The plan might well achieve its goals and represent a great solution for certain flooding patterns. However, as is often the case with landscape design and engineering, the solution might also be provisional. The question that remains open is if the plan effectiveness will be reduced by changing rain patterns and how layers of historical interventions will interact with such a future scenario. Reclaimed land, diverted rivers, forgotten creeks, and streams play a crucial role in the patterns that are followed by storm waters. It is not clear if the plan took such history into account, although some aspects seem to be partially informed by a historical perception, particularly in an effort to mimic the river’s original topography. A more systematic historical perspective would enhance important reflections on the interactions between the river and the urban fabric, with its shifting economic and cultural assets. Since the plan already aims to presents the river as a pedagogical site (17), it would be interesting to create learning opportunities that also aim to prompt flood culture as a preventive civic tool.

Engaging with local historical research contributes to enhance a different perception of the site’s present-day configuration and provides people with more accurate tools for developing a sense of flood risk and awareness. River flooding which often occupies the margins of our imagination, and thus rarely activates our sense of risk, has been in fact increasing and is expected to increase even more over the coming years, according to research presented in the Annual Disaster Statistical Review and in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. An intellectual engagement with a relational history of flood can enhance levels of awareness and thus reduce those psychological post-flood impacts, particularly anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, which are often unaccounted for and have been highlighted by recent publications such as Climate Change and Public Health, edited by B. S. Levy, and J. A. Patz and published by Oxford University Press. From this perspective, risk is not to be understood in Ulricht Beck’s sense as “the perceptive and cognitive schema” that “opens a world within and beyond the clear distinction between knowledge and not-knowing, truth and falsehood, good and evil” (5-6). On the contrary, an adequate discussion of the conditions that produce flood moves stories of flood away from the semantics of dreadful risk towards a vision of the future that is shaped by an informed sense of risk.

I became interested in the history of the Trinity River in Northern Texas because continuous warnings for local flash floods prompted me to wonder why flooding could occur in inland Texas. The site unsettled the axioms of my European sense of Texas by introducing unexpected elements such as green grass, magnificent trees, abundant rain, and encroaching waters. Acknowledging the Trinity River prompted me to reflect on the history of the relationship between settlers, water, and land in the Dallas/Fort Worth area. The river also prompted the crucial questions on flooding that opened this reflection.

Is it appropriate to classify each flood occurrence in relation to spatio-temporal categories, particularly in public historical discourse? Wouldn’t it be more effective to refer to each flood in relation to the specific processes that caused it? Engaging with more detailed stories of individual floods would contribute to enhance a defined sense of risk which is easier to navigate than undefined fears of the inexplicable and the unexpected. This informed sense of risk is as important a prevention measure as works of engineering, STEM, and public science.

Luna Sarti is a Ph.D. candidate in Italian Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research explores the shifting cultures and practices of water that bound the Arno river in Florence. In her dissertation, she analyzes site-specific medieval and early modern narratives of flooding to discuss if, when, and how flood is to be considered a “natural disaster.”

Featured Image: Flooded Homes Near Downtown Fort Worth in 1949 Flood of Trinity River (accessed June 24, 2019), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; courtesy of Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room.