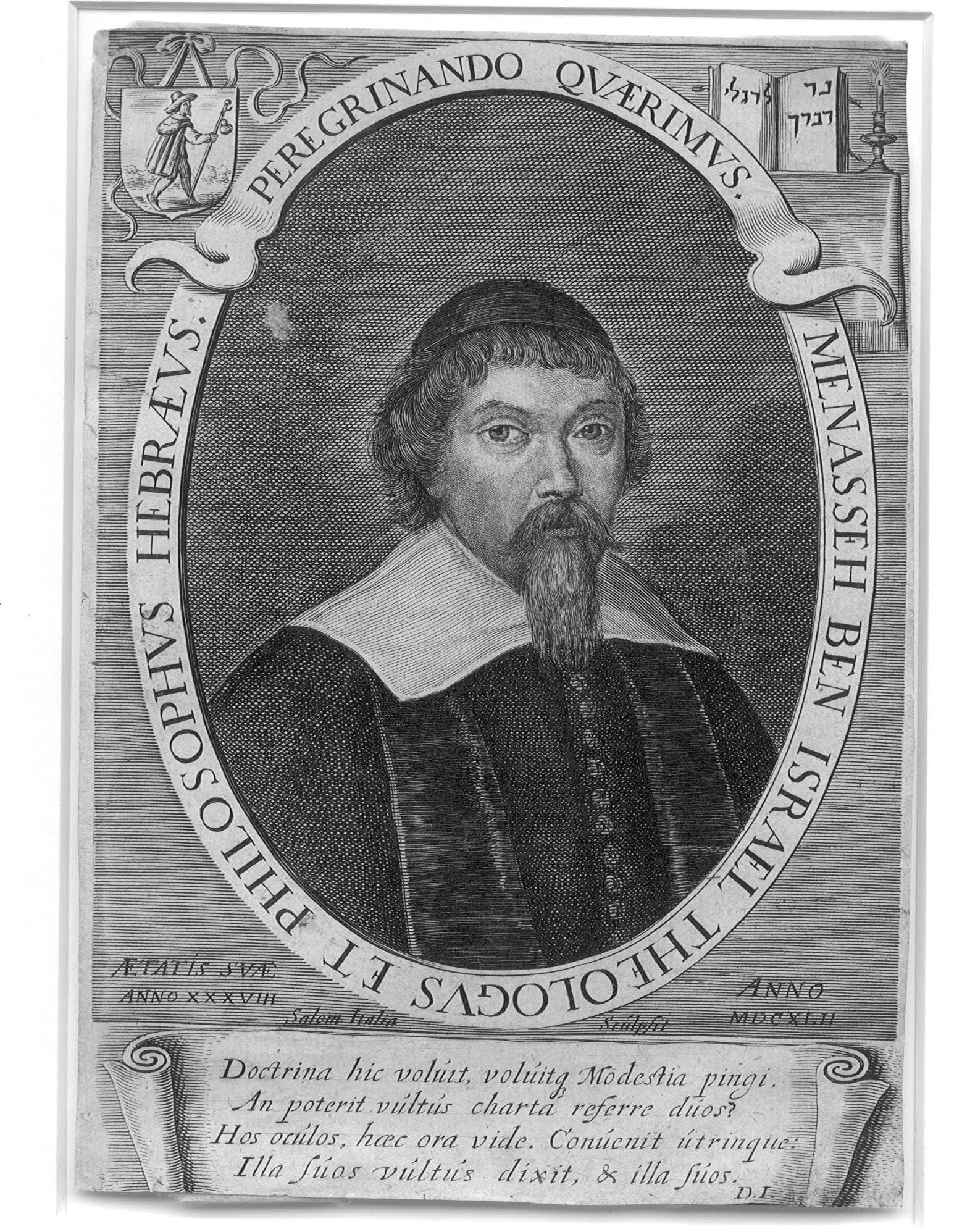

By Professor Steven Nadler

Read Professor Nadler’s full article from this season’s JHI, “Spinoza and Menasseh ben Israel: Facts and Fictions.”

It just goes to show: even a rabbi can sometimes bend the truth a little, especially in the heat of debate.

In this article, I considered how, during his 1656 “friendly and extemporaneous conversation” in London with the Huguenot minister Jean d’Espagne, the Amsterdam rabbi Menasseh ben Israel claims that the Jewish people do not “anathematize” people. Here is the exchange:

Menasseh: Do you think our rabbis are fools?

D’Espagne: Well, at least crazy. For what do you think about those who think and speak about God in such a blasphemous way? Indeed, why do you not anathematize them?

Menasseh: We are not accustomed to cursing people.

As I note, Menasseh’s remark is striking because this debate took place just two months before Menasseh’s own Talmud Torah congregation of the Portuguese-Jewish community of Amsterdam decided to “excommunicate, expel, curse and damn” the young Bento de Spinoza for his “abominable heresies and monstrous deeds”, punishing the future philosopher with the most extended and vitriolic herem (ban or ostracism) ever pronounced by the parnassim (leaders) of that community.

What makes his remark even more interesting is that Menasseh himself was once put under herem by his community. Here are the circumstances:

In early 1640, according to a report in the community’s record book, some anonymous individuals had “put up certain posters or defamatory papers on the doors of the synagogue, on the bridge, at the market and in other places.”[i] The placards, which the report says touched on “the subject of Brazil”, were apparently impugning the business practices and character of certain members of the community involved in the South American trade (mostly sugar). Most likely they were directed at well-established merchants who did not appreciate any new competition and so were making things difficult for others seeking to enter the market. Dishonorable behavior in commerce was one thing, and it would be dealt with, but publicly shaming fellow congregants was yet a more serious violation of the community’s regulations. This kind of insolent behavior could not be tolerated. “It is well understood by all that this deed is abominable, reprehensible, and worthy of punishment.” And so, on February 9, 1640, the members of the ma’amad issued an at-large punishment on the unknown culprits.

We put under herem and announce that the person or persons who have made such papers and posted them are cursed by God and separated from the nation. Nobody may speak with them or do them a favor or give them assistance in any way.

A herem was an act of banning or ostracism (often, somewhat inaccurately, translated as “excommunication”) used by the Amsterdam parnassim to punish congregants who had violated communal regulations and generally to keep people in line. It was a form of religious, social and economic isolation. A person under herem was usually forbidden from participating in synagogue services, as well as from socializing and conducting any business with members of the community. It was an effective measure for maintaining Jewish discipline and social order among relatively new Jews—many of the Amsterdam Sephardim were, or descended from, former conversos—still getting used to an orthodox life.

Soon after the libelous posters appeared, the ma’amad learned who the guilty parties were—Daniel Rachaõ and Israel da Cunha—and the ban was applied to them the very next day. (It was lifted on Rachaõ a week later after he expressed contrition for his actions.)

However, a short time later, the ma’amad discovered that Jonah Abrabanel and Moses Belmonte were also involved in the “Brazilian matter”, either as participants in the original escapade or by circulating new posters again suggesting that certain Portuguese-Jewish merchants were less than honorable. Abrabanel and Belmonte were each given a herem, but were soon back in good standing after expressing deep and sincere remorse for their behavior and paying their fines.

Menasseh, however, was incensed by the way in which Jonah Abrabanel, his brother in-law, had been treated. He, of course, as Jonah’s partner, shared his sentiments about the merchants who were seeking to monopolize the Brazil trade, and he may even have been involved in distributing the offending material. But even more, Menasseh felt that the ma’amad had shown great disrespect to Jonah when the whole affair was made public in the synagogue during services, not least by failing to accord him the honorific title senhor when his name was read out. Menasseh lost his temper and protested loudly from the rabbis’ bench. According to the report of the ma’amad, “Menaseh [sic] came from his place and, with loud voice and all worked up, complained that his brother-in-law was not called ‘Senhor‘ – giving him the title that was owed to him.” The congregation’s gabbai responded that Abrabanel did not deserve the title, as it was to be used only with sitting members of the ma’amad. This only made Menasseh madder.

A large part of the assembly left its place, whereupon Menasseh turned on them, without being willing to calm himself, as he was continuously warned to do, until finally two parnassim of the synagogue stood up in order to make him be quiet, and indeed, since they could not do it with sufficient words, used the punishment of herem. They ordered him to stop and to return to his house. He countered with a loud voice: he would not. Then the parnassim, who were in the synagogue, came together, and since the disturbance continued further, they confirmed the punishment of the herem in order to make him [Menasseh] stop, and they ordered as well that no one speak with him.

The members of the ma’amad retired to their chambers, whereupon Menasseh followed them, burst in and

raising his voice and pounding on the table, said in a serious fashion all the unbridled thoughts that came into his mind, so that finally one of the parnassim apprised him that he is the cause of various disturbances … the parnassim told him to leave the chamber and that they regarded him as cut off. He responded to that with loud voice that he was putting them under herem and not the parnassim him, and other such shameful things.

It was an impressive display of righteous indignation. Out of respect for his position and years of service to the community, the ma’amad took some pity on him. Menasseh’s ban, recorded on May 8, 1640 and imposed “for the insubordination, the scene, and the curses, which he had spoken four times”, was in place for only one day.[ii] From sundown to sundown, he was forbidden from entering the synagogue and communicating with any members of the community. On top of that, however, “to serve as an example to others”, he was suspended from his rabbinical duties for a year. It was a heavy penalty for what was regarded as a serious breach of decorum. Unlike his brother-in-law, there is no indication that he ever expressed remorse for his behavior.

[i] The ma’amad‘s records of the event, from which the quotations that follow are taken, are in the Livro dos Acordos da Naçao e Ascamot, in the Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Archive 334: Archives of the Portuguese Jewish Community in Amsterdam, Inventory 19 (Ascamot A, 5398–5440 [1638–1680]). See fols. 55–56 and 69–70. These pages are accessible online as #71, 78 and 79 at https://archief.amsterdam/inventarissen/inventaris/334.nl.html#A01504000004.

They are transcribed in Carl Gebhardt, Die Schriften des Uriel da Costa (Amsterdam: Menno Hertzberger, 1922), pp. 212–19.

[ii] Livro dos Acordos da Naçao e Ascamot, fol. 70, accessible online as #79 at https://archief.amsterdam/inventarissen/inventaris/334.nl.html#A01504000004. On 8 September 1647, the page on which the herem against Menasseh was recorded was pasted over with a piece of paper by the ma’amad, “out of respect.”

1 Pingback