By Jonathon Catlin

“I am not at all afraid of the term ‘ivory tower,’” said Theodor Adorno in a Der Spiegel interview three months before his untimely death in 1969. The German critical theorist had been accused of being politically “resigned” by the same Frankfurt student activists who had credited him as an inspiration in 1968: He cultivated a “liturgy of critique” in the hallowed halls of the university, they said, but then rejected their radical calls for violence against the state as mere “tactics” and “actionism” born of despair rather than liberation. In response to students asking, ‘‘What is to be done?’’ Adorno said, “I usually can only answer ‘I do not know.’ I can only analyze relentlessly what is.” In December, 1968, Adorno signed an open letter entitled, “we support the protest of our students.” But one month later he called the police on students occupying his institute. They and his old friend Herbert Marcuse never forgave him. Adorno’s last course was disrupted by the so-called “breast assassination,” in which students rushed the podium demanding that he renounce his earlier positions. They scrawled on the chalkboard: “If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease.” Three female students bared their breasts and showered him with flower petals. He fled the hall, and students distributed a leaflet: “Adorno as an Institution is Dead.” He cancelled the rest of his course and went on holiday to Switzerland, where he died of a heart attack. In his last weeks he complained to Marcuse: “Here in Frankfurt, the word ‘professor’ is used condescendingly to dismiss people, or as they so nicely put it ‘to put them down,’ just as the Nazis used the word ‘Jew’ in their day.”

These days, there is good reason to fear the pejorative “ivory tower.” It has now been shown that many of America’s more than 4,000 colleges and universities perpetuate inequality more than they advance class mobility. This means that the story many institutions have been telling us about increasing access and the American dream is at best a fiction and at worst an ideological cover for deeply unequal outcomes. The numbers behind these trends are striking. Washington University in St. Louis takes the cake for the most “elite” college in America: 84 percent of students come from the top fifth of family incomes, and 21.7 percent come from the top one percent alone. Only 6.1 percent of students come from the bottom 60 percent, and less than one percent come from the bottom fifth. The median parental income of all students at WashU is $272,000. At Dartmouth, over one fifth of students come from families earning $630,000 or more per year. Can such institutions be called “democratic” when they so disproportionately serve the American aristocracy? In light of such figures, the recent college admissions scandal implicating Felicity Huffman is merely a flare-up shedding light upon broader structural inequalities—the pin that may have finally burst the balloon of colleges’ meritocracy myth.

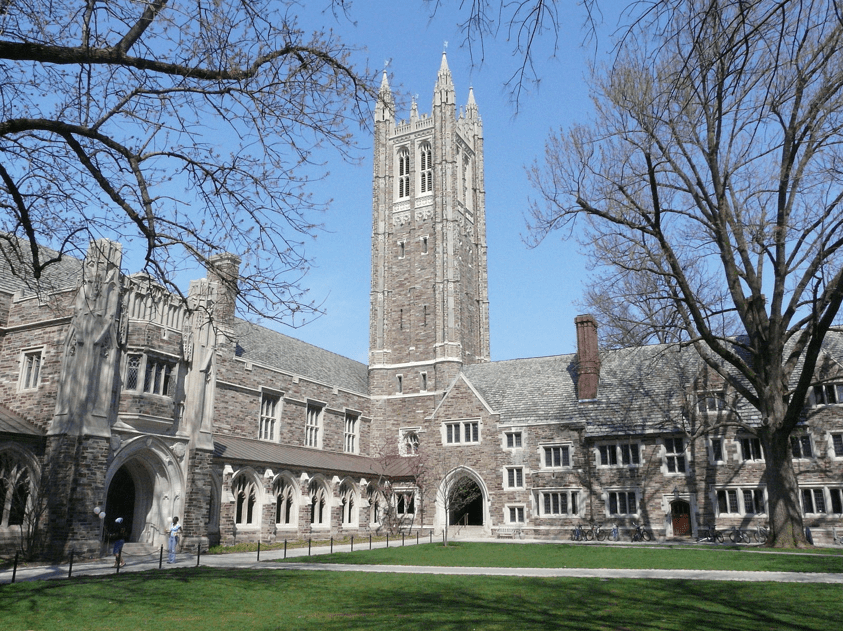

Taking a stroll around my university campus at Princeton and reading the names of the buildings offers a lesson in the history of capitalism: Rockefeller, Firestone, Forbes, Bloomberg, Icahn, Whitman (these days, all eyes are on Bezos).

Elsewhere in the Ivy League, Harvard’s art museum still bears the name of the Sackler family, which made billions selling deadly opioids. My own stipend as a Princeton graduate student comes in large part from an endowment given to my department by the investment mogul Shelby Cullom Davis. Yet precisely because of its privileged access to elite wealth, Princeton—the richest university in the world on a per student basis—also has a robust financial aid program that allows students to graduate with some of the lowest debt levels of any American institution. This fact makes for more than nice headlines defending elite universities’ right to hold onto their enormous endowments. For behind those other familiar headlines about soaring tuition rates (this year the University of Chicago became the first institution to break the $80k threshold) lies the growing practice of what economists call price discrimination: Students from wealthy families are now asked to pay more through increased sticker prices, but this can also enable the majority of students from more modest backgrounds to pay little or nothing. Nevertheless, many elite colleges disproportionately enroll and reproduce the “professional-managerial class,” and less wealthy universities continue to saddle poor and middle-class students with debts as high as six figures. Is it at all surprising that the majority of elite universities built by and for elites facilitate—and then normalize and legitimize—the growing inequality of American society?American academia can indeed be called “democratized” in more than one sense. Professors registered as Democrats outnumber Republicans 10 to 1. Yet the resulting self-perception of being “progressive” also blinds many academics from recognizing the production of inequality in their own midst. In sheer numbers, enrollment in U.S. colleges and universities has grown in the past several decades, partly as a result of recruiting international students. 36 percent of Americans ages 25–34 now hold a bachelor’s degree, a figure that continues to rise. However, the number of students enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities peaked in 2010 and has since declined slightly. Small, rural, and women’s colleges in particular are struggling with rising costs and tuition fees, declining state funding, and falling enrollment due to a “demographic crisis.” Confronting these limits to growth may help us recognize that these issues will not resolve on their own. Similarly, sending all Americans to college, the elusive dream of Barack Obama, is not a panacea for deep racial and economic inequalities. Too many students haven’t been adequately prepared for college to succeed once there. As Yale professor Daniel Markovitz writes in his new book The Meritocracy Trap, the “academic gap between rich and poor students now exceeds the gap between white and black students in 1954, the year in which the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education.”

A recent anthology of Keywords for academic life writes: “the function of academia in its current form (if not always its explicitly stated mission) is that of the university in its modern configuration: service to the global economy through the production of monetizable knowledge, together with the rearing of students into desirable employees for profitable firms.” William Deresiewicz’s 2015 polemic Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life similarly bemoaned elite college students like those he once taught at Yale selling out into profitable industries. Since 2007, he writes, about half the graduating class at elite schools including Harvard and Princeton have gone to work in finance or consulting (p. 17). Between 1995 and 2013, the number of top-ten colleges with economics as their most popular major increased from three to eight—“a stunning convergence.” Hence the late Yale alumna Marina Keegan puzzled in 2011 as to why her alma mater bothers to attract the most gifted students in the world, with myriad interests and passions, when it spits out a plurality of them into finance and consulting: “I conducted a credible and scientific study in L-Dub courtyard earlier this week—asking freshman after freshman what they thought they might be doing upon graduation. Not one of them said they wanted to be a consultant or an investment banker.” It’s not just the cost of college and professional school and aggressive recruiting by big firms that fuels this exodus from creative, public, and non-profit sectors into today’s dark satanic mills of finance capitalism, where the levels of burnout and depression are as outrageously high as the salaries. It’s also that elite universities indoctrinate students into a culture of what Cornel West dubs “neoliberal soulcraft”: “I want to be smart. I want to be rich. I want to have high-visibility.”

I’m now a private school brat, but this world is relatively new to me. I was born to a lower-middle class single mother in northern Wisconsin but adopted by relatives who lived in the white, upper-middle-class suburbs of Chicago, where everyone went to good public schools. The Northeast’s culture of elite private high schools was alien to me. But then I went to the University of Chicago, a school than provides relatively limited social mobility and financial aid compared to peer institutions. It occurred to me at some point in my first year that about half my friends there were either legacies or had siblings who had also gone there. This helped me put a finger on what it meant to be “first-generation to college,” an otherwise obscure box I had checked on my applications. The contrast of spending my days studying in a literal ivory tower and then stepping off campus into extreme urban poverty made America’s deep racial and class divides palpable for me. I was puzzled when students I knew who came from the most privileged backgrounds and had gone to high schools like Andover and Exeter took up jobs they didn’t need at alternative student coffee shops and dressed in shabby, thrifted clothes. They attired themselves and imbibed like my father, an uneducated long-haul truck driver who drank cheap liquor from plastic bottles. It felt to me like Marie Antoinette playing poor in her peasant village at Versailles. But this game of dress-up didn’t negate class distinctions and privilege when it came time to graduate and many such students ended up working in tech or finance.

Contrast this with a very different experience: Some of my closest friends and colleagues attended and were politically radicalized at Montreal’s McGill University, which is sometimes called “the Harvard of Canada.” There’s one essential difference between these institutions. McGill is an elite public university, an expression almost oxymoronic to American ears. Tuition costs in Canada are lower and enjoy more public support. Many faculty and staff are unionized and regularly strike alongside students, adjuncts, and graduate workers. Solidarity is built into the structure of the university. Public systems like Canada’s or the U.K.’s no doubt perpetuate inequality in myriad ways, channeling privileged students disproportionately into coveted places at McGill and Toronto or Oxford and Cambridge. Still, these are all public universities. When tuition fees are raised, students protest nationally. When faculty pensions are under threat, workers from the most elite universities strike alongside local and regional ones.

I often imagine how much more equitable American higher education could be if it were considered a public good. Of course, in the fabled golden age of the GI Bill, one could get a terrific public education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where funding, faculty governance, and tenure were gutted by former Republican governor Scott Walker, or the University of California at Berkeley, which until 1975 was tuition-free for state residents; the 54 percent of its budget provided by the state in 1987 has shrunk to 12 percent today. Public systems like the City University of New York, once known as “the public Harvard,” is one of the country’s rare genuine engines of class mobility but increasingly defunded and in disrepair. Luckily, some state (New York, New Mexico) and local (San Francisco) initiatives are picking up the slack to ensure access to quality education at public universities and community colleges.

Blocking these vital efforts to reinvest in higher education there lies a powerful conservative defamation campaign that exemplifies all the risks of retreating into the “ivory tower” today. One of its main charges is unfortunately true: that academia is too often an isolated, liberal, and out-of-touch bubble—as was realized in the disastrous intellectual failure of so many academics to foresee Trump’s election. An “education gap” now maps onto the partisan divide in American politics: Educated people increasingly vote for the Democratic Party, which in certain respects has recently become “the party of the elite.” In 2016, 57 percent of college graduates reported voting for Clinton and only 36 percent for Trump. Nate Silver wrote that education was “the critical factor” determining who voted for Trump: “Education levels may be a proxy for cultural hegemony. Academia, the news media and the arts and entertainment sectors are increasingly dominated by people with a liberal, multicultural worldview, and jobs in these sectors also almost always require college degrees. Trump’s campaign may have represented a backlash against these cultural elites.” This partly explains why colleges have become the latest battlefield in the culture wars: 59 percent of Republicans now think higher education has a negative impact on the country, a figure that has nearly doubled since 2012. The reported reasons: liberal bias among professors and a culture of protecting students from offensive views. Watch an episode of Tucker Carlson—hardly a fringe figure, as his show is one of the highest ranked on cable and watched by millions—and you’ll hear him rant about “safe spaces” and political correctness, while he frames conservatives as victims of liberal thought police and as martyrs defending “free speech.” It’s worth quoting at length a recent feature of Carlson’s on the student debt crisis:

We can’t begin until we reform the student loan system. Why haven’t we done that yet? Well, a hugely powerful lobby stands in the way—colleges and universities. Their lobbyists swarm Washington. Not surprisingly, these are the people who benefit from student loan debt. Drive through rural America, and you see how well they’ve done. In a sea of poverty and despair, you will notice gated islands of affluence. These are colleges. Outside the gates, people are unemployed and dying of opioid overdoses. Inside the gates, it’s like the Ritz on South Beach. If you haven’t been to an American university lately, see it for yourself. Everything is new. There’s been a building boom underway for decades on campuses, all of it funded by debt that is destroying a generation of American kids. A hundred schools now have endowments over a billion dollars. They are hedge funds with schools attached.

Conservatives like Carlson depict universities as decadent and snobbish—the ivory tower with a new steel and glass facade, surrounded by a lazy river. The 2017 Republican tax bill that now taxes university endowments higher than $500,000 per student is rooted in these cultural biases. On the one hand, such policies contradict conservatives’ purported economic priorities, for universities serve as major engines of research, innovation, and training for the economy. But it is also rooted in the understandable feeling that many universities have too long been in effect private instruments of the wealthy and do not serve the whole citizenry. A handful of Carlson’s talking points raise actual issues: bloating student debt, debt-fueled campus building, and overpaid administrators. But when he describes colleges as a “scam” and “racket,” he conflates the essential work they do in our society with fraudulent and for-profit institutions that are still in need of regulation—an issue Democratic presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren has done much to address. In reality, there are gaping yet solvable structural problems behind the student debt crisis, including declining state funding and predatory for-profit loans. (“Once that sustainable public funding was taken out from under these schools,” The Atlantic noted last year, “they started acting more like businesses.”) But Carlson merely directs his populist animus at cheap targets, like the idea “that taxpayers should shoulder all the risk so that Wesleyan or Brown can build another diversity and inclusion center and hire more useless overpaid Deans of Sensitivity.” Meanwhile, politicians on the Left are busy structurally rethinking how college is paid for.

The term university, says Keywords, derives “from the Latin substantive denoting the all-encompassing totality of the universe as such,” which “apparently came to designate this circumscribed pedagogical entity without irony.” What happened to this grandiose mission? How did we let our universities give up on it? “And yet,” the entry concludes, “universities do remain significant (potential?) sites of resistance to the increasingly pervasive incursion of market forces into every aspect of individual and collective existence.” As Foucault taught us, sites of power are also sites of possible resistance. Yet today “resistance” within the American academy takes a very different form than the ’68ers’ campaign against Adorno. Students are no longer against the university as such, seeing it as a conservative bastion of tradition aligned with the state; rather, they now aim to use the university’s power for their own progressive ends—twisting the arms of image-conscious administrators until they recognize and defend students’ values. Faculty are no less assimilated into “corporatized” university culture: No matter how “critical” one’s academic posture, teaching and scholarship ultimately serve to perpetuate the institutions that enable them. For the growing academic precariat, most efforts are simply directed toward securing an elusive living-wage position in a system in which only 25 percent of jobs are now tenure-track. These grim realities leave academics, not unlike their students, “always already” professionalized, pursuing success as the existing system of incentives and opportunities has defined it. This bind makes the task ahead all the more daunting: to challenge American higher education’s glaring complicity with rising inequality, lest current disdain for the ivory tower become justified.

Jonathon Catlin is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM) at Princeton University. His dissertation in progress is a conceptual history of “catastrophe” in modern European thought, focusing on German-Jewish intellectuals including the Frankfurt School of critical theory.

Featured Image: Holder Hall (1911), part of Rockefeller College at Princeton University Wikipedia.