By Cindy Kok

Look closely at the lower left corner of Jan Weenix’s 1693 group portrait: a pineapple grows amidst a cluster of exotic plants (Fig. 1). At first glance, Weenix’s depiction of this family suggests a familiar narrative of Dutch Golden Age wealth and success. To the right, merchant Sybrand de Flines (1623-1697) wears a luxurious kimono-inspired robe; his wife and children pose at a country estate, surrounded by objects of knowledge and art. However, Weenix draws the viewer’s attention to the pineapple, composing the family members in a diagonal leading to the plant. In addition, the artist shows the pineapple on its stem—still relatively small—rather than an imported ripened fruit.

Why is an American botanical a focal point of this composition? More than a family portrait, Weenix’s painting celebrates matriarch Agneta (Agnes) Block (1629-1704) and her achievements as a naturalist and botanist. Scholarship on women naturalists has highlighted their role in shaping a domestic relationship to European exploration. Botanical illustrations by artists like Maria Sibylla Merian and Rachel Ruysch—as well as the images’ afterlives in crafts like embroidery—made fragments of the larger world accessible to a European audience (Tomasi, “La femminil pazienza,” 160; Kinukawa, “Science and Whiteness as Property in the Dutch Atlantic World, 93-94). Block, however, purchased an estate outside Amsterdam in 1670 to engage directly in theoretical and experiential sciences from which women were commonly barred (Fig. 2). In 1687, she successfully grew the first European pineapple plant in the Vijverhof hothouses. With her pineapple, and this portrait, Block locates herself intellectually within a network of (predominantly male) European naturalists taxonomizing, codifying, and propagating the flora and fauna of the New World.

European explorers did not discover the pineapple, nor were they the first to cultivate it. Pineapples are indigenous to the tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, originating between the Paraná and Paraguay rivers (where modern-day Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay meet) (Okihiro, Pineapple Culture, 74). Native Americans first domesticated the plant for its fruit, which they believed stimulated the appetite and aided digestion. By the seventeenth century, the pineapple is well-documented in European writings such as Pietro Martir de Anghiera’s De Orbo Novo and Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdéz’s Historia General y Natural de las Indias.

Oviedo describes the pineapple as having a “beauty of appearance, delicate fragrance, [and] excellent flavor” that affects all the senses in a way in which “none of the other fruits…can compare, by many carats” (Oviedo y Valdéz, Historia General y Natural de las Indias, in Collins, 9-14). He quantifies its value in commercial terms typically reserved for precious materials. Indeed, European interest in the pineapple grew with trading companies’ investment in commercial botanicals, or “green gold” (Schiebinger, “Prospecting for Drugs,” 119). Plantation owners cultivated these profitable plants in American and Asian territories; trading companies carried the products back to eager consumers in Europe. Undergirding this imperial economy was the study of natural sciences, which used European scientific methods to monetize plant resources from outside territories (De Vos, “The Science of Spices,” 401-402). Block’s pineapple, particularly its reliance on hothouses that replicated equatorial colonial climates, is inextricably linked to this imperial-commercial complex.

To have greater control over cultivating tropical plants, gardeners had to understand how to manage the instruments of a hothouse. The Dutch first pioneered the design and use of hothouses in 1685, prompting European elites to send their gardeners to the Netherlands to study Dutch methods and buy Dutch pineapple plants (O’Connor, Pineapple, 24). Most prominently, Gaspar Fagel, adviser to stadhouder William of Orange (later William III of England), established a tropical garden at his estate Leeuwenhorst; after his death, part of his collection transferred to Hampton Court in 1689, accompanied by Dutch gardeners who maintained, expanded, and documented the collection (Arens, “Flowerbeds and Hothouses,” 266). The European gardener needed to be a mechanical as well as a natural scientist, bringing together technical knowledge with field and laboratory research (Fleischer, “Rooted in fertile soil,” 1). Hothouse technology, in combination with botanical knowledge, allowed gardeners to grow tropical plants year-round in cold Europe, subverting natural seasons and climates.

The hothouse became a way to appropriate even the environment of South American territories, overcoming distance, reordering non-native plants in a European taxonomy, and controlling them with European science. The wealthy and well-educated Block deployed this new technology at Vijverhof. In the humid hothouse, she planted a pineapple slip—a tuft of leaves taken from the base of the plant—acquired from the collection of tropical and subtropical plants at the Horticultural Garden in Leiden (O’Connor, Pineapple, 24; Oviedo y Valdez, Historia General y Natural de las Indias, in Collins, 12). Most likely she learned this indigenous American method of propagating pineapples from books such as Oveido’s. Although Block’s work intersected with colonial botany—whereby imperialists acquired and deployed indigenous knowledge—she was uninterested in growing pineapples commercially. Rather, her success was a personal achievement that gained her access to European intellectual and cultural networks. Vijverhof became a center for other painters and naturalists like Merian, Herman Saftleven, and Jan Commelin to study rare specimen firsthand.

Before the development of hothouses, the pineapple had been elusive: difficult to preserve in the transatlantic journey, impossible to grow in cold northern climates. Its rarity made it an impressive diplomatic gift. When unable to purchase the expensive fruit, English noblemen could still rent a pineapple to display at important dinners (Thompson, “Pineapples”). According to legend, royal gardener John Rose gifted a pineapple to his patron King Charles II in the 1660s. Although the pineapple was likely imported and not even grown in the royal gardens, Hendrik Danckerts chooses this career-defining exchange to commemorate Rose upon his death (Fig. 3). The moment of presentation, as mythologized by Danckerts, is ceremonious: Rose kneels before Charles presenting the pineapple, as if symbolically offering his monarch all the botanical resources of the New World.

Rose and Charles pose in front of an English estate, the gardener holding the pineapple as if it were a flower. Danckerts’ constructed image erases the origin of the pineapple and the work and knowledge of the indigenous American cultivators who grew it; he implies that the plant originated from the estate, reinforcing this idea with visual echoes of pineapple plants in leafy pots surrounding the fountain. The artist places Rose at the center of the narrative, positioning the European gardener as procurer of New World goods and proprietor of scientific botanical knowledge. Similarly, in her portrait, Block claims credit for the pineapple, seamlessly incorporated into her surroundings. Although central to his painting, Weenix situates the plant among other foreign flora and symbols of knowledge within a European landscape. These portraits fictionalize global natural history, perpetuating a narrative in which the pineapple is only available when mediated by European expertise.

Block also facilitated the normalization and circulation of the foreign through images. In particular, her successful cultivation of a pineapple prompted her to adopt it as her personal emblem. Around 1700, Albert van Spiers illustrated a frontispiece for an album of drawings Block collected from Heroldt (Fig. 4) (“Design for a floral frontispiece with a portrait medallion of Agnes Block”). The floral wreath includes Block’s portrait medallion, discussed below, as well as her family’s coat-of-arms. Floral motifs were popular for frontispieces but Spiers customizes his illustration for Block’s album by using tropical flowers, many of which he likely studied in her garden. Even the scales of the gold frame recall segmented pineapple fruit. In her visual program, exotic botanicals become associated with Block’s personal identity, rather than with non-European peoples or places. Once the botanicals are transplanted to her estate, they become absorbed into Vijverhof’s knowledge base for Block to (re)distribute.

Block also commissioned a portrait medal by Jan Boskam that references her expertise in horticulture (Fig. 5) (Vander Ploeg Fallon, “Petronella de la Court and Agneta Block,” 103). On the recto, the phrase “Flora Batava,” or Dutch Flora, is stamped alongside Block’s profile; on the verso, an anthropomorphized figure of Nature holds a tulip—originally from Turkey but popular and valuable in the Netherlands—and gestures to Block’s gardens at Vijverhof. To the right of Nature, as in the Weenix portrait, are a cactus and a pineapple plant, crown jewels of Block’s garden.

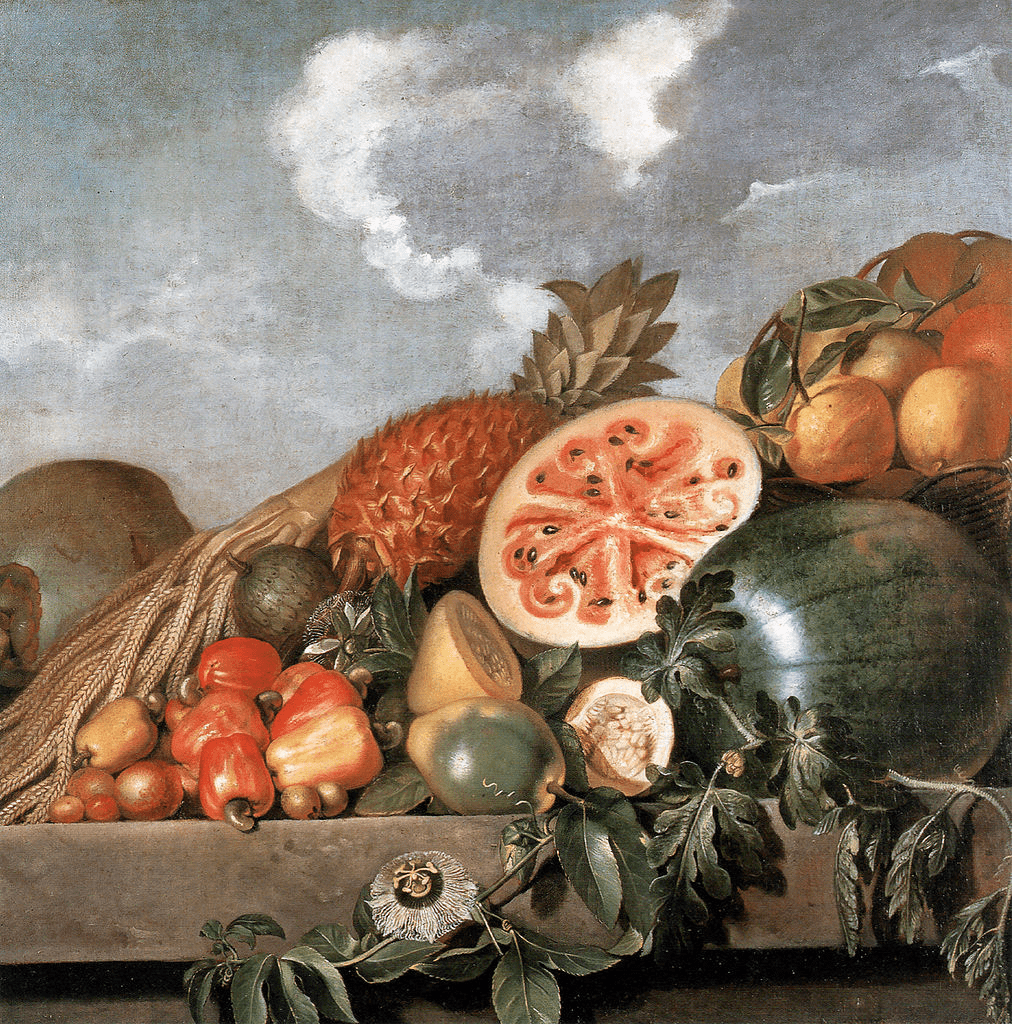

In this idealized vision of the garden, the tools of Block’s work, such as the hothouse, are elided in favor of a more mythical narrative about the bounty of nature with which Block (like the Dutch Republic) is blessed. With the non-native flora, Block mimics a guild tradition of stamping medallions with signs of membership to a network of like-minded specialists (Weinstein, “The Storied Stones of Altona,” 573). Block symbolically joins the ranks of professional naturalists and, like them, collects and fits knowledge into a European framework. Long before pineapples were widely available for consumption, Block assimilates the imagery and disseminates it. Unlike artists like Merian and Albert Eckhout, who traveled to the Americas and painted pineapples as symbols of foreign bounty (Fig. 6), Block’s pineapple is presented as a Dutch product integrated into Dutch gardening.

The modern age of the Anthropocene has inherited this notion that human interventions—from hothouse pineapples to ethylene-ripened bananas—allow us to master and improve upon nature. Yet even with naturalists’ attempts to scientifically regulate and define plants, the living specimen remained inherently unstable and mutable (Arens, “Flowerbeds and Hothouses,” 272). In spite of the advantages afforded by the hothouse, gardening was always characterized by this European struggle to control colonial resources and manage the demands of nature. The visual, however, remained easier to manipulate and, while not her explicit goal, Block patronized work that reinforced the visual scheme of empire. Botanical gardens and natural sciences, long considered politically neutral in scholarship, actively facilitate a Europeanization of knowledge taken from indigenous sources through processes of imperialism. The images that emerged in conjunction with natural histories and accounts of curiosities achieve similar ends, eliding a sense of locality to privilege European centrality. Through her experiments and visual rhetoric, Block similarly displaces the pineapple to relocate it in a European sphere. By placing exotic fruits in her portraits, medallions, and printed material, Block expresses a sense of possession that reflects a Dutch understanding of their relationship to the New World.

Cynthia Kok is a PhD candidate in the History of Art department at Yale University. Her work investigates the global circulation of material and ideas in an early modern Dutch world; she is currently working on a dissertation on mother-of-pearl.

1 Pingback