Here’s what our editors have been reading lately:

Jonathon

Dark Lens: Imagining Germany, 1945, by Françoise Meltzer (Chicago, 2019). A fascinating study of the ethics of visually representing catastrophe, based on photographs taken by the author’s own parents, an American man and French woman who met in the ruins of Berlin in 1945. Meltzer starts from the positive fascination with ruins developed by the 18th and 19th century Romantics and still evident in the writings of Sigmund Freud—a frequent traveler to classical ruins in Greece and Rome and an avid collector of antiquities. She argues powerfully that such romanticization of destruction becomes untenable “after Auschwitz” (Adorno) and after the mass murder of millions of civilians through air warfare in the Second World War. Meltzer uses the detached, ethically leveling quality of photographs of destruction to show that if all lives really are of the same value then war against civilians can never be ethically justified.

History in Times of Unprecedented Change: A Theory for the 21st Century, by Zoltán Boldizsár Simon (Bloomsbury, 2019). The argument of this provocative new work in theory of history is summed up in its two sentences: “Contrary to common belief, history is not concerned with the past. It is all about novelty.” Zoltan Boldizsar Simon develops a theory history for the “end of history” that is fundamentally based on disruption rather than conventional models of narrative continuity and progress. This book thinks at the cutting edge of an important contemporary epochal change that historians have not yet been able to grasp: The Anthropocene. An open-access excerpt from the book on how impending ecological catastrophe exemplifies the work’s broader thesis defining history as “bringing about the unprecedented” can be found here.

The Anthropocene: Key Issues for the Humaniteis (Key Issues in Environment and Sustainability), by Eva Horn and Hannes Bergthaller (Routledge, 2019). An impressive “conceptual map” designed to introduce students and scholars alike to the latest research on one of the most important concepts for virtually all fields in the humanities today. The challenges of understanding the unfolding ecological catastrophes of the Anthropocene are many: unprecedented planetary scale, altered visibility and invisibility, diminished sense of human agency, and a new relation to history, all unfolding through new and unstable temporalities. Chapters provide a historical genealogy of the concept (and its competitors, like Capitalocene), a theory of the Kantian sublime of planetary aesthetics, a reconsideration of the politics of the “anthropos,” and reflections on “deep time.” This work provides a much-needed, if tentative, guide to conceptually grasping the unfolding reality of ongoing climate catastrophe.

Spencer

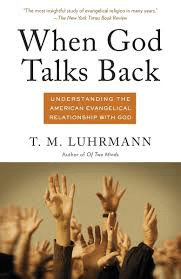

Tanya Marie Luhrmann’s aptly titled When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God (2012) interrogates a remarkably common experience in contemporary American life—two-way conversations with the Almighty. A distinguished anthropologist, Luhrmann spent years immersing herself in the world of the Vineyard, a fast-growing movement within global evangelical Protestantism, for whose members God is powerfully, palpably present in every moment and every choice of their day-to-day lives. Guidance from on high is forthcoming on career moves and medical crises, to be sure, but also on the right outfit for the day and the best muffin recipe. More than a fascinating ethnography of American evangelical culture, When God Talks Back brilliantly draws out the nature of religious belief, anywhere and anywhen, as a practice one learns and hones, a practice often strikingly at odds with the evidence of our senses and our common sense.

A rather different take on the nature of belief came from Richard Rorty’s Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979), a devastating critique of philosophy’s centuries-long assumption that the mind is a representation of the world, a mirror (sometimes well-polished, usually not) reflecting reality. This has been, for Rorty, the source of no end of misery for philosophers and their readers, with many of the “fundamental” problems of the discipline revealed as the artifacts and unintended consequences of this conceptual habit. For me, the encounter with Rorty was a salutary reminder that disciplines—not unlike Luhrmann’s analysis of faith—are languages one must learn (and practice). My philosophy is rudimentary, and rusty at that.

To round out my reading in suitably Trinitarian fashion with a third book on belief, I devoured Ann Leckie’s The Raven Tower (2019). A towering figure in contemporary science fiction, Leckie has now trained her talents on fantasy, producing a novel of political intrigue and wars waged with magic that is simultaneously a thoughtful reflection on divinity and the meaning of worship. What does a god owe their worshippers? And how do gods die?

Simon Brown

About a week ago the University of California fired 54 student workers at UC Santa Cruz after a prolonged wildcat strike. The strikers refused to post grades, teach or research until they received a cost-of-living adjustment that could ease the punishing rent burden of living in such an expensive city, on such little pay, in the midst of a housing crisis. Since then our UC campuses have been abuzz with graduate students rallying, petitioning and insisting that they, like any workers, deserve to make enough to live here. In the midst of these conversations I return again and again to the question of that relationship between the student and the worker in our own intellectual labor. We are fortunate to have a new guide to help us think through it. I’ve been reading a new edition of Max Weber’s Vocation Lectures, presented here as “The Scholar’s Work” and “The Politician’s Work,” edited by Paul Reitter and Chad Wellmon, translated by Damien Searls and published in the New York Review of Books Classics series. Weber opened his famous lecture on the scholar, after all, not with his influential discussion of “disenchantment,” but with a sober account of the working conditions, hiring structure and low pay of academics up and down the scholarly hierarchy.

The Introduction (a version of which was published by the Chronicle Review) recreates the context in which Weber delivered his lectures to a group of liberal students in Munich, the first at the height of war and the second in the political instability of its aftermath. With attention to those moments Wellmon and Reitter read Weber as neither a nostalgist for intellectual life before disenchantment nor as an advocate for technocratic specialization. Rather, he resisted the calls from both liberal students and conservative critics to return education to the imagined project of moral cultivation. The modern scholar ought to be a specialist in a disciplined community of colleagues, and that expertise did not extend to the deepest moral question. Still, he required those religious virtues, like faith that his work would have value, that he associated with Protestant “Vocation.”

We might feel such a balance, or tension, when we work as student instructors or as student researchers. We might feel called to this work, and we might feel responsible for students’ education. Weber’s lecture, and this brilliant new edition, help us see that that does not diminish our status as workers, or make that work any less modern.