By guest contributor Jake Newcomb

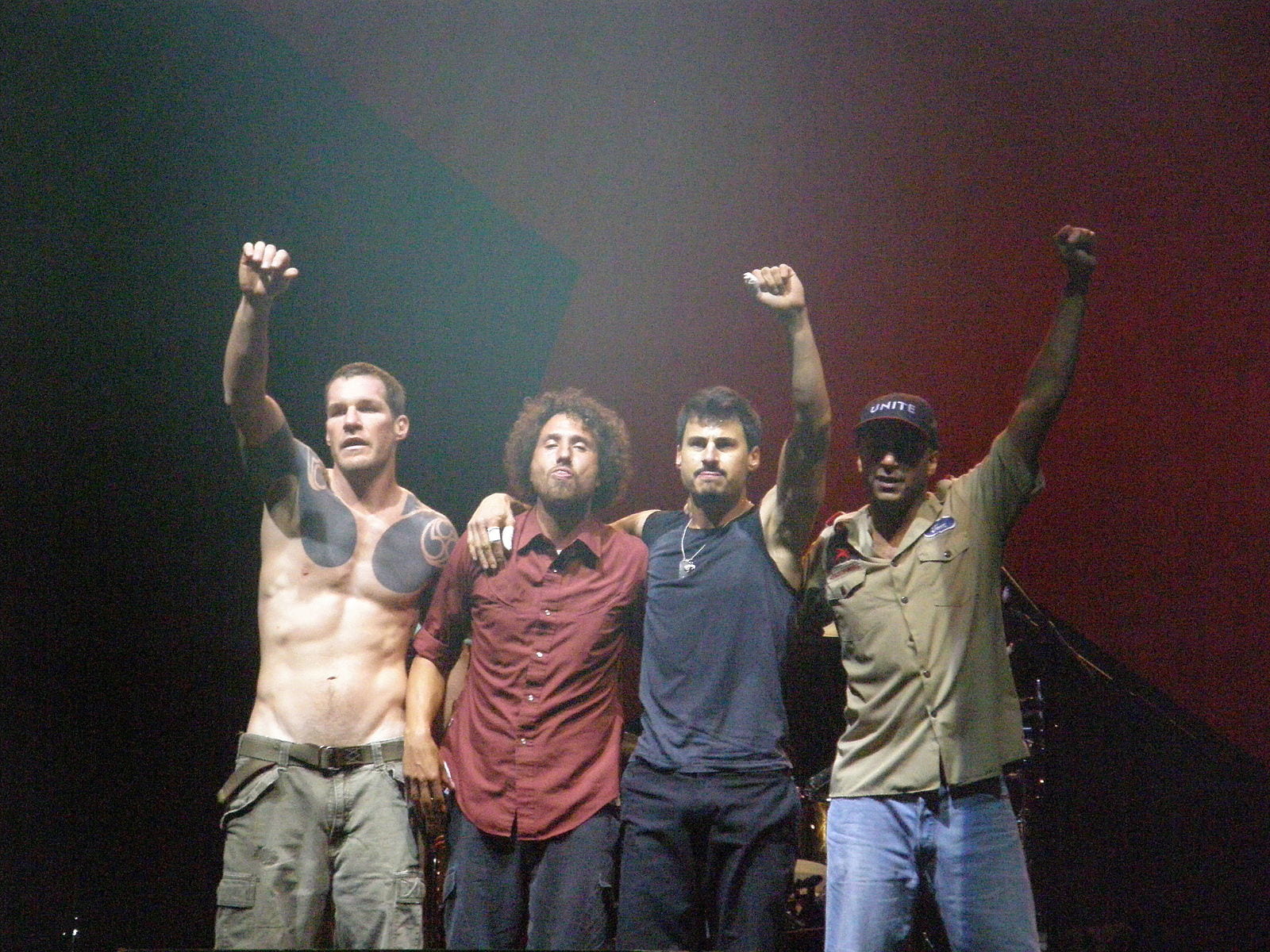

The music world has been abuzz this year with the reunion of Rage Against The Machine, whose reunion world tour includes a headlining stint at Coachella in April. Rumors of the imminent return have abounded since a spin-off band (Prophets of Rage) formed in 2016 to protest the “mountain of election-year bullshit” that emerged that year. Prophets of Rage’s lineup consisted of the instrumentalists of Rage Against The Machine with Chuck D (of Public Enemy) and B-Real (of Cypress Hill) performing vocals in lieu of Zack De La Rocha, the vocalist of Rage Against The Machine. Guitarist Tom Morello stated back in 2016 that they “could no longer stand on the side of history. Dangerous times demand dangerous songs. Both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are both constantly referred to in the media as raging against the machine. We’ve come back to remind everyone what raging against the machine really means.” Prophets of Rage embarked on their “Make America Rage Again” tour in 2016, and they even staged a demonstration outside the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, an attempted repeat of Rage Against The Machine’s renowned performance directly outside of the Democratic National Convention in 2000, on the street in Los Angeles. Now, Zack De La Rocha has returned to complete the reunion. Their “Public Service Announcement” tour was scheduled to begin on March 26th, in El Paso, Texas, as a response to the domestic terror attack there last August, but in light of the global COVID-19 pandemic, they have postponed all the shows scheduled between March and May. The July and August legs of their world tour are, as of now, still on schedule.

Aside from their signature sound, Rage Against The Machine (hereafter RATM) are most commonly beloved and denounced for their commitment to radical politics, which has commanded significant attention by fans and critics alike. Their songs are public stances taken on some of America’s most polarizing topics: police brutality, wealth inequality, globalization, racism, and the two-party system, the media, and education. They also publicly embraced radical movements outside of the United States, like the Zapatista movement against NATO during the 1990s. Culturally, their fame and left-wing politics have seen them associated with figures like Michael Moore and Noam Chomsky, both of whom RATM has worked with in some capacity. Their politics are often discussed as inseparable from their music (aside from the bizarre case of Paul Ryan, who claimed to enjoy their sound but hate their lyrics) since their political stances and statements are viewed as a key component of their entire act. What is much less discussed, or analyzed by scholars, however, is RATM’s presentation of history. This is surprising, because RATM’s music engages in a “re-casting” of history, not unlike Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, with the past a recurring element of their lyrics. The historical narratives in the songs identify the downtrodden as the protagonist, continuously battling multiple, interlocking spheres of oppression (a.k.a., The Machine) over centuries. This generations-long struggle, and the consistent oppression of the poor and weak, gives urgency to lyrics such as, “Who controls the past now, controls the future. Who controls the present now, controls the past,” a direct homage to George Orwell. Breaking out of this cycle of history is what RATM preaches.

On their first album, released in 1992 as Rage Against The Machine, RATM’s songs argued that the education system, the media, and the state worked in tandem to brainwash the population into believing false historical narratives and fake news. De La Rocha specifically took aim at public school curriculums and teachers that forced “one-sided” Eurocentric histories down the throats of pupils. This false narrative (of American history), accordingly, celebrates and obscures the violent realities of “Manifest Destiny” ideology as well as stripping non-white students of their historical and cultural identities, in order to assimilate them into American society. The true narrative, according to the lyrics, is a history of racial and economic oppression at the hands of both the state and private corporations, who have succeeded in no small part over the centuries by actual and cultural genocide. Further, this false narrative of history interlocks with contemporary false media reports and psychologically-manipulative advertising that keep the population docile, obsessed with consumer products, and supportive of oppressive class and racial relations. They sing that the United States is trapped in a loop that perpetuates injustice, ignorance of that injustice, and ignorance of the history of that injustice. This is the loop they first called their fans to rally against.

Despite the unique rap-metal denunciation of “The Machine” that RATM presented on this first album, those familiar with historiography from the 1980s and 1990s will recognize the similarities between their presentation of America’s past and those of others. Compared with popular historiography, RATM presents similar longue durée historical claims as A People’s History of the United States and Lies My Teacher Told, according to which the long-term history of oppression and exploitation in the United States has been long-obscured by false, nationalistic history. Like RATM’s albums, these books were massively successful, although in the latter case, their popularity derived explicitly from their depiction of history. RATM’s presentation of history was present, but it was (and is) obscured by their denunciation of contemporary politics, their revolutionary slogans, and their distinctive sound. Of course, these shifts in popular historiography to initiate a change in the dominant narrative of history also emerged in academic historiography, as with the Subaltern Studies group. Scholars like Ranajit Guha and Gyan Prakash published works on India that tried to move beyond the British colonial and Indian nationalist narratives that obscured the lives of “subaltern” Indian populations and the exploitation they suffered at the hands of colonialism and industrialization alike. Women and gender scholars also prominently emerged at this time to analyze long-term subjugation of women and gender minorities as well as address the lack of women’s historical contributions in academic historiography. RATM’s music can be viewed as an extension of these historiographic shifts into the world of music, specifically the emerging world of alternative rock and rap. Their inclusion alongside this historiography also points to a broader cultural moment, whereby the traditional historical narratives broke down.

RATM continued to expand their historical commentary throughout their initial run in the 1990s, even going so far as to start their second album with the lyrics, “Since 1516, Mayans attacked and overseen…” in the song “People of the Sun.” The song is an anthem of support for the Zapatista movement in Southern Mexico, who De La Rocha visited before writing the second album. While politically the song was written as a song of support with the Zapatistas, the song associates the struggles of the Zapatistas with others in a long history of oppression in Mexico, dating back to Spanish colonization. So on their second album, RATM continued to address long-term historical trends that repeat over time, which they asked their listeners to fight against. They bring the long-term historical trends into the third and final studio album as well, 1999’s The Battle of Los Angeles. For example, in the song “Sleep Now In The Fire,” De La Rocha identifies many difficult historical topics as being aspects of the same long-term phenomenon: violent greed, specifically in the context of colonialism, slavery, and war. The crews of the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria are part of the same lineage as the overseers of antebellum plantations, and the wielders of agent Orange and nuclear weapons. De La Rocha also suggests in the lyrics that Jesus Christ has historically been invoked as the ultimate justification for various forms of greed or intense violence, pushing that lineage back millennia.

While music as history is nothing new (in fact, for some cultures, history has traditionally been expressed through music), it is rare to find such an explicit historical dimension in contemporary popular music in the West (although, some intrepid historians have begun interpreting western music and art as history). Not only did RATM present their fans with a unique sound and highly-charged politics in the 1990s, but they also advocated for a historiographical framing that paralleled changes happening in popular and academic historiography. Along with Subaltern Studies and A People’s History of the United States, for example, RATM asked listeners to shift their historical focus to the lives and stories of the oppressed, instead of glorying the rich and famous. This historical framing, no doubt, was tied to RATM’s political project, as were the writings of Zinn and Guha. And like Guha and Zinn, RATM’s productions (cultural rather than intellectual) became both highly influential and targeted by critics. RATM has not announced any plans to record and release any new albums, so the jury’s out on whether there will be any new takes on history from De La Rocha and co. What’s likely though, is that thousands of fans will pack out stadiums this summer to sing along with RATM’s radical history if the COVID-19 pandemic subsides in the United States and Europe.

Jake Newcomb is an MA student in the Rutgers History Department, and he is also a musician. He can be followed on Twitter and Instagram at @jakesamerica

May 12, 2020 at 10:20 am

Great post, Jake. I agree that popular music is a largely untapped source for historians and how historical views get get out to the general public.

I’ve written on the historical content of a recent Drive-By Truckers album (and they’re often interested in the history of the South): https://erstwhileblog.com/2017/10/25/american-band-drive-by-truckers-and-history/

as well as the environmental content in Neil Young’s catalogue (https://erstwhileblog.com/2020/04/22/the-environmentalism-of-neil-young/). His views are less historically sophisticated, but there’s something to be said for the history he has dabbled in since the 1970s.