Jonathon Catlin

The Los Angeles Review of Books published a collection of quarantine reflections by a wide array of intellectuals, ranging from a hilarious domestic scene by the affect theorist Lauren Berlant to this sobering meditation on medicine and racial inequality by Saidiya Hartman: “Many of us live the uneventful catastrophe, the everyday state of emergency, the social distribution of death that targets the ones deemed fungible, disposable, remaindered, and surplus. For those usually privileged and protected, the terror of COVID-19 is its violation of and indifference to the usual distributions of death. Yet, even in this case the apportionment of risk and the burden of exposure maintains a fidelity to the given distributions of value. It appears that even a pathogen discriminates and the vulnerable are more vulnerable…Who lives and who dies? I fear the answer to such a question. I think I know what it is.”

Samuel Clowes Huneke, “An End to Totalitarianism,” Boston Review. A helpful post-mortem on the concept of “totalitarianism,” which was employed by Cold War thinkers including Hannah Arendt and Carl J. Friedrich to conflate fascism and communism. The term long ago exhausted its analytical usefulness for historians but has recently witnessed another popular revival to describe Trump and leaders who seek to exploit the Coronavirus crisis for authoritarian ends. Huneke aptly characterizes the danger of this terminology: “The ideological work that the term totalitarian performs is significant, providing a sleight-of-hand by which to both condemn foreign regimes and deflect criticism of the regime at home.”

Andrew Marantz, “Studying Fascist Propaganda by Day, Watching Trump’s Coronavirus Updates by Night,” New Yorker. A profile on the Yale philosopher Jason Stanley, who has become a notable public intellectual in recent years for his books How Propaganda Works (Princeton, 2015) and How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them (Random House, 2018). Among its insights: “Trump’s habit of extolling the heartland while decrying urban squalor ‘makes sense in the context of a more general fascist politics, in which cities are seen as centers of disease and pestilence.’ Stanley couldn’t have known that many American cities were, in fact, about to become centers of disease, but he could have predicted that Trump would use such a development to his rhetorical advantage. ‘Some people would like to see New York quarantined because it’s a hot spot,’ Trump said, late last month. ‘Heavily infected.’”

Federico Marcon, “Historical Knowledge, Historians’ Categories, and the Question of ‘Fascism,’” in the critical Asian studies journal positions. A historian of knowledge in early modern Japan, Marcon reflects on the challenges of writing a history of the concept of fascism, a topic a few centuries outside his area of specialization. Criticizing a recent flurry of works on fascism, Marco makes a strong case against the “generic concept” model that sees “fascism” as applicable to our present. Fascism, he writes, “is a term that is, one the one hand, overloaded with meanings and, on the other, is, at closer investigation, surprisingly fuzzy and meaningless.” Against the proliferation of the concept, Marcon concludes, “the name ‘fascism’ is ultimately a disadvantage for our understanding of the different forms of voluntary dis-emancipation of the last hundred years.” His broader reflections on the historical discipline identify him closely with the Theory Revolt collective the JHI Blog has covered in recent years: “In today’s post-theoretical age, in which the naïve notions that historians’ job essentially consists in reporting archival findings and that archives give historians unmediated access to the past seems once again pervasive, reflections on the cognitive practices of historians are preciously untimely. Self-reflection, once the province of ‘theory’ and today largely disavowed, has the important function of accounting for historians’ cognitive labor and its consequences.” How, Marcon asks of those historians putting too much stake in the inconsistent—even incoherent—category of fascism, does one’s conceptual apparatus contribute to creating the past one strives to reconstruct?

Exemplifying the “generic concept” approach to fascism Marcon criticizes, the New School historian Federico Finchelstein has published an excerpt from his new book A Brief History of Fascist Lies (California, 2020) at Public Seminar.

The Chronicle of Higher Education asked scholars including Maya Jasanoff, Steven Salaita, Samuel Moyn, and David Halperin for their favorite scholarly book of the decade.

A new podcast by Jacobin, Casualties of History, discusses E.P. Thompson’s seminal The Making of the English Working Class (1963), with Alex Press and historian Gabriel Winant.

David Kettler and Thomas Wheatland speak on the podcast New Books in Intellectual History on their new book about an often-neglected member of the Frankfurt School, Learning From Franz L. Neumann: Law, Theory and the Brute Facts of Political Life (Anthem, 2019).

Pranav Jain

The title should be enough to convince you to read this most fascinating of articles. If not, consider what happened in Paris when Hans and Parkie, two elephants brought in from Sri Lanka, refused to copulate:

“The institutional efforts reached their apex in a professional concert performed on 10 prairial of the Revolutionary Year VI (May 29, 1798) by musicians from the Parisian Conservatoire de la musique, featuring some of the most renowned contemporary performers. Following Hans and Parkie’s earlier reluctance to engage in the desired activity, it was thought they could be stimulated by a rich musical program played from a purpose-built platform behind them. The concert for the elephants included, among other pieces, extracts from Rameau’s opera Dardanus, his rival Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Le Devin du village, Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, a symphony by Haydn, and Revolutionary songs like “Ça ira.” While Rousseau’s music seemed to excite both elephants “into joyfulness,” it was the third performance of “Ça ira” (in D Major and with multiple voices) that reportedly rendered the female particularly aroused. The male elephant seemed to play along for a while before losing interest”

Luna Sarti

Spending time in the house, my attention has increasingly (perhaps dangerously) been shifting toward the invisible processes that are necessary to produce the privilege of a safe domestic space. The topic is complex and difficult, but I started with Maria Kaika’s City of Flows, particularly chapter 4, where the author discusses the invisible network of piped waters and their role in the making of “the detached, self-contained space of the home” (50). Thinking about cold water pipes, water heaters, and domestic sewage puts Latour’s discussions of infrastructures in Paris: Invisible City into new light. While there is a tendency to think about “invisible” infrastructures as universal objects, the materiality of such infrastructures is weirdly entangled with local cultures and economic systems. In spite of international building codes (such as the NEC, the NESC, or the IEC for electric and the IPC or Eurocodes for plumbing), in fact, local amendments, aesthetic sensitivity, and shifts in the market contribute to rearrange the components of infrastructures in ways that can be readable, but unpredictable. With these texts in mind and a network of “unknown” infrastructures making the “envelope of space” around me (Kaika, 50), I started reading Norman Pounds’ Hearth and Home: A History of Material Culture (Indiana University Press, 1989) and Maureen Ogle’s All the Modern Conveniences: American Household Plumbing, 1840-1890 (Johns Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology, 2000). In spite of its questionable use of the wonder narrative, I also enjoyed watching David Massar’s historical documentary Plumbing which was originally broadcast on the History Channel. Being increasingly aware of my dependence on people who have both theoretical and practical literacies in the infrastructures I live with/on, I also started diving into blogs that offer insight into those sets of knowledge.

Nuala Caomhánach

Bullshit. Bad science. Charlatans. Fake news. Coverups. Trust. Conspiracy. UFO’s. Way back when I taught an undergraduate course called “Science and Pseudoscience”. The course was a broad survey of a hodge-podge of themes, concepts and categories—from The Death Star, Psychic Phenomenon, Evolution, Climate Change to Alien Abduction–and was one of the most engrossing teaching experiences I have yet to have. For what it’s worth, the student population was ethnically diverse and male-student dominated (25 male: 5 female). The students approached this dichotomy as a simple demarcation problem, however, the security of their own knowledge systems quickly morphed into a quagmire of crises as the stability of their culturally and socially informed worldview collapsed.The dichotomy of science and pseudoscience often devolved into arguments over whether or not the data was “right” or “wrong”. This stamp of validity was their gold standard for Truth or Non-Truth.

Today, the coronavirus pandemic has created novel sites for misperceptions, misinformation, and the uncomfortability of listening to friends, families, communities and nations arguing along anti-intellectual, anti-science and anti-”truths” lines. Having sat performing judgment-filled inner-eye rolls to suppress my allergic reaction to an uncle’s argument that God sent this plague for those who have sinned—-as my brother loudly preaches that the pandemic is part of a global political hoax—I squirmed as i wondered why I had ever assumed my logic was more “Truth-ful” and more rational than theirs. The copious amounts of over-brewed tar tea did not settle my unease, and left me wondering–what comfort and control do we both “get” in digging our heels into our closed-off (and perhaps smug) opinions? How is information, care and safety constructed and maintained during national crises for groups of people with different value systems? And why are there no biscuits left for this cup of tea?

“Bullshit is a widely recognized problem” stated sociologist Joshua Wakeham, in Bullshit as a Problem of Social Epistemology (2017). Wakeham offers the reader 20 pages of “bullshit” as a primer to reframe this concept as a problem of social interaction. This fascinating read highlights the tension between the individual pragmatic need to have “true” beliefs and the social pragmatic desire to “get along” and not rock the boat. The paper explores how naturalized this concept has become within everyday social spaces– the workplace, social media, colleges, and politics. His analysis asks ”[H]ow do we decide whose claims to believe?” Wakehams study suggests that an individual’s own experiences play a limited role, and we rely on a series of value systems from our social context to evaluate the credibility of secondhand knowledge. Thus, notions of authority, self-worth, presentation and trust operate rapidly in whether the individual absorbs this information as an accurate claim. Wakeham argues, however, that these heuristics operate as a positive feedback loop as the very social pathways (or social norms) that we rely on to make these risk/benefit evaluations are not designed for the task of epistemic vigilance.

In The roles of information deficits and identity threat in the prevalence of misperceptions (2017), political scientists Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler explore how diverse populations within the United States hold misperceptions. The authors present three case studies to explore the mechanics of human misperceptions–the troop surge in Iraq, job change under President Obama, and global temperature change. This fascinating study found that providing information in graphical form reduced misperceptions and lessened the threat to an individual’s self-conception or worldviews. Their results suggest that misperceptions are caused by a lack of information that melds with the feeling of a psychological threat, factors that offer more pathways to understand how individuals hold their worldviews in the face of new and opposing information.

The following books are teacher and student-friendly books to critically engage with issues surrounding what defines good, bad and ugly science, and how we trust what we think we know about the world. Michael Shermer offers a starting point for the neophyte in Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (2002). The book covers many complex issues–such as cults and Holocaust deniers—to explore the human reasons that draws people to their belief systems. Shermer himself is a curious fellow–a former theology student, a self-identifying skeptic, and an incredible writer–that many students in my own course were unable to locate Shermer’s own biases. A must for critical thinking skills.

The Historian of Science, Michael Gordin offers the beautifully written and engrossing The Pseudoscience Wars. Immanuel Velikovsky and The Birth of the Modern Fringe (2002). The book centres on Immanuel Velikovsky, a Russian-born psychoanalyst, who settled in the United States in 1939. His book Worlds in Collision (1950) rewrote the early history of the world using a wide selection of non-science sources that Velikovsky argued mapped out the real historical events. He argued that Venus was a cometary ejection from Jupiter and that the orbital instability of Venus, Mars, and other planetary bodies was a consequence of as-yet-unexplained electromagnetic forces between them, counteracting the effects of gravity. Astronomers were outraged for two major reasons. First, Velikovsky’s claims about Venus seemed un-scientific and implausible, and second, it was not “science” so why did the division of the Macmillan Company publish the book at all. Gordin’s narrative traverses the rise and fall of Velikovisky from a scientist, a pseudoscientist, and a martyr to an anti establishment movement in the context of the Cold War, the McCarthy era, Lysenkosim and the sudden rise of American science to unprecedented prominence. Gordin’s book is an excellent example of the history of demarcations. Two other books that are useful teaching-textbooks are, David Raup’s The Nemesis Affair: A Story of the Death of Dinosaurs and the Ways of Science (1999) and Massimo Pigliucci Nonsense of Stilts. How to Tell Science from Bunk (2018)

Lastly, a selection of recent articles that touch on the topics discussed above. In Dealing with Conspiracy Theory Attributions (2020) social scientist Brian Martin analyzes the methods, effectiveness and audiences of academic myth debunking efforts. In Coronavirus: the spread of misinformation, medical surgeons Areeb Mian and Shujat Khan discuss the disconnect between scientific consensus and scientific communication with the public on topics such as climate change, vaccine science and safety and the shape of the earth.

Simon

Edward Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963) has entered the canon of modern historiography through countless graduate seminar syllabi, and that is how I first read it. It was sandwiched between the Annales School and Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, a position which would have likely horrified Thompson. We read it as a response to a “vulgar Marxism” that made no place for workers’ “experience” or “agency” because it had room only for rigid classes and economic laws. Thompson was not writing against this foil, however, but rather against and with a cohort of socialists, particularly in Britain, who were trying to understand the future of their political movement in the midst of rising working-class affluence, a declining empire and a deteriorating hope in the Soviet Union. I’ve been reading The Making of the English Working Class again and trying to understand it within that moment and its debates, and I’ve been doing it alongside the new podcast from Jacobin Radio, “Casualties of History,” dedicated to a close reading of the classic, its context and its critics.

The podcast is hosted by Alex Press, a writer and editor at Jacobin, and Gabriel Winant, a historian at the University of Chicago. Thompson wasn’t writing just for scholars and future historians. He was writing within a socialist movement pulled in different directions by factions, publications and intellectuals to whom activists might look to represent what the left was supposed to be. Thompson’s essays and his Making intervened in contentious debates with Marxist thinkers like Perry Anderson, Tom Nairn and Raymond Williams over the possibilities for organizing a working-class movement in Britain and the role of intellectuals within it. Those issues would have felt particularly pressing to Thompson’s cohort of radical historians who wrote their formative work while teaching in the Workers’ Education Association. The hosts elaborate on their sometimes convoluted series of overlapping debates conducted largely in the pages of New Left Review. When it’s read among a pantheon of the most influential historical works of the half century, this urgent politics of The Making recedes into the background. This podcast explores how the book helps us understand class formation in the early decades of industrialization, and what it has to say to leftists and socialists today

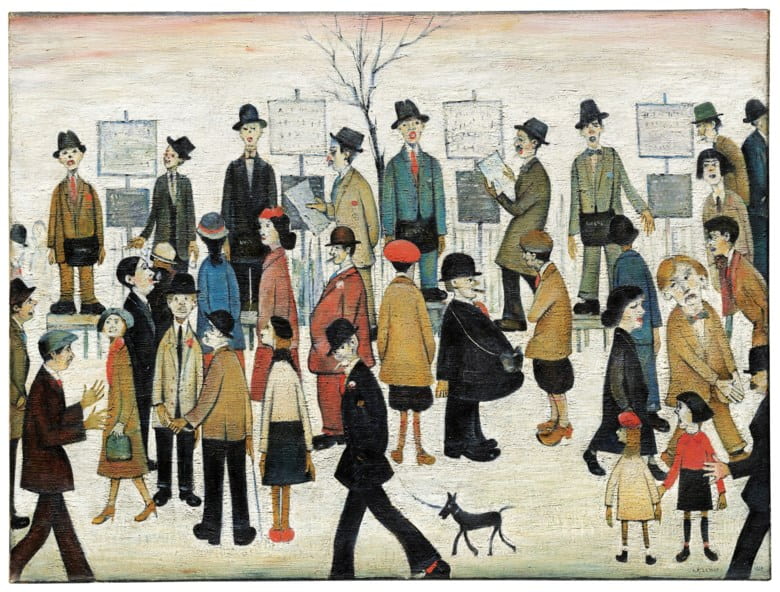

Featured Image: L.S. Lowry, A Northern Race Meeting (1956). Courtesy of WikiArt.