By Jonas Knatz and Anne Schult

Stuart Elden is Professor of Political Theory and Geography at University of Warwick. His publication series on Foucault includes Foucault’s Last Decade (Polity, 2016), Foucault: The Birth of Power (Polity, 2017),The Early Foucault (Polity, forthcoming), and The Archaeology of Foucault (Polity, forthcoming). Beyond Foucault, he most recently authored Shakespearean Territories (University of Chicago Press, 2018) and Canguilhem (Polity, 2019). He runs a blog at www.progressivegeographies.com.

Jonas Knatz / Anne Schult: The current Corona pandemic has engendered a heated debate about Michel Foucault’s oeuvre and its contemporary relevance. In late February, Giorgio Agamben and Jean-Luc Nancy publicly debated the Italian declaration of a state of exception. Commenting on this debate, Roberto Esposito turned the discussion of government authority in times of crisis into a reexamination of the Foucauldian “paradigm of biopolitics.” In a similar vein, Bruno Latour saw us “collectively playing a caricatured form of the figure of biopolitics that seems to have come straight out of a Michel Foucault lecture”, for which he was criticized by Joshua Clover. Panagiotis Sotiris took this one step further and reflected upon the possibilities of a democratic or even communist biopolitics. Philipp Sarasin, meanwhile, suggested that Foucault’s three-tiered model of governing approaches to combating pandemics, which he developed out of the historical cases of leprosy, plague, and smallpox, offers a more relevant tool of analysis than biopolitics, which was a term only fleetingly used by Foucault himself. Do you find Foucault’s writings a useful starting point for understanding the contemporary moment?

Stuart Elden: I’m very grateful for the interest in doing this interview, so I’m sorry to start off with a refusal to answer the question! I have been collating various pieces by philosophers, geographers, sociologists and others on my blog Progressive Geographies, but I really don’t have anything of my own to say. Like everyone else I’ve been fascinated and horrified by what is happening, and obsessively checking news and social media feeds. Putting together a few links on the blog quickly grew into something more, as I found more pieces, or was sent links. But I think there is something of a tendency to rush to have something to say, and much of what I’ve seen has been hurried and sometimes with a quick application of an existing theoretical position, often without much detailed knowledge of the specific moment. I’ve just turned down a request to write a chapter in an edited collection on this topic. At the moment I think it is public health voices we need to hear, epidemiologists and others. The time for more humanities and social science reflections will come, but I don’t think that is now – at least for me.

Foucault’s work is naturally seen as relevant and here it is not simply the case of connecting his work in a tangential way. As you indicate, he really did write about clinical medicine, what went on in hospitals, different approaches to diseases and public health. There is the well-known beginning of the ‘Panopticism’ chapter of Discipline and Punish, when he discusses the spatial and political order of a plague city. There are some remarkable lectures he gave in Rio in 1974 on public health and medicine, developing from some collaborative work on hospitals as ‘curing machines’, which is where his essay ‘The Politics of Health in the Eighteenth Century’ was first published. My Warwick colleague Daniele Lorenzini has just written a really good piece about all this. There is the work on leprosy, smallpox and so on in other lectures, in Paris and elsewhere. But most of this work was historical, looking back at periods with a view to discerning trends and patterns. And Foucault was always very cautious about seeing too easy parallels between the past and the present. There is also something of a general wish to ‘use’ Foucault’s ideas in an instrumental way, when most of his concepts and tools were developed to make sense of quite specific times and places, and when he turned to different histories and geographies he developed new ones. Part of what I’ve been trying to do with Foucault the past several years has been to resituate his ideas in their contexts, rather than see them as approaches that can be easily used in other settings.

JK / AS: In 2016, you published Foucault’s Last Decade, in which you trace Foucault’s development from 1974 to 1984. Foucault: The Birth of Power, which came out in 2017, complements this study by examining the years from 1969 to 1974. In addition, you are currently working on a third volume in this series, which offers an analysis of Foucault’s work from 1949 to 1961, and you recently announced that you agreed to publish a fourth, final book about Foucault’s intellectual activities in the 1960s with Polity Press. Do you consider this series an intellectual biography—or rather, as you suggested on your blog regarding the first volume, an observation of the genesis of Foucault’s intellectual milestones? In what ways would you describe your undertaking as different, especially with regard to methodology, from the more “traditional” portraits of Foucault offered by Didier Eribon and David Macey?

SE: I am full of admiration for the work Eribon and Macey did. I read those books first when I was writing my PhD, in the mid-late 1990s, and thought they were both really useful studies. As I’ve continued work on Foucault I’ve found more and more ways to recognise and appreciate them. They often capture in a few lines or pages what we can now reconstruct in great detail given what is now accessible, but to which they didn’t have access. Eribon in particular established the broad contours of the Foucault story, and Macey was indebted to his work. Both made use of extensive interviews with people who knew Foucault at all stages of his life, and Eribon in particular did some valuable work with archival sources and other unpublished documents. It’s less known in English, since the translation is of the early edition, but Eribon’s book is expanded in its present 2011 French edition with some valuable new material. But both books were written before the lecture courses at the Collège de France were published, and lots of new material has come to light since. I wrote an afterword to the recent reedition of Macey’s biography with Verso that tries to survey some of this, and have been trying to persuade publishers to translate the third edition of Eribon’s text and his 1994 book Michel Foucault et ses contemporains, both of which are invaluable sources.

I have been asked by a couple of publishers if I’d write a new biography of Foucault, given the new material that has become available. But I’ve declined to do this for the simple reason that I don’t think I could do it better than Eribon and Macey. There are huge new resources for writing about Foucault’s work – the Collège de France courses and some other teaching materials, transcripts of radio programmes, the fourth volume of the History of Sexuality and so on. There is a lot more to come, much based on the archives now available to researchers at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. But there are not that many new sources for understanding Foucault’s life. His correspondence is largely unavailable, and much seems not to have been kept – I’ve seen some letters mainly from the early 1950s, but family correspondence is restricted until 2050. And Daniel Defert told me that Foucault usually threw away letters that he received after reading them.

Eribon and Macey had access to a large number of people that Foucault knew – family, teachers, colleagues, students. Foucault was only 57 when he died, and so not only were many of his contemporaries still alive, so too were people of an earlier generation who had taught or mentored him. Foucault would be over 90 now had he lived, and so the majority of people who still remember him knew him in his later years. And memory is fallible – Eribon and Macey were interviewing people within a few years of Foucault’s death. Unless and until the correspondence becomes available, I can’t see how Foucault’s life could be discussed better. But his work – that I think we can say something useful about in the light of these new materials. So, I’ve tried to resist the idea that I’m writing biography, but rather describe it as intellectual history. Though I recognize that there isn’t a clear distinction, and that especially with the earlier periods I’m working with many more biographical materials. This is partly because the resources for this period are more limited – far fewer publications, interviews, records of lectures, etc. – and so I’m making use of whatever materials I can find to tell the story.

JK / AS: Your Foucault series follows a somewhat unusual sequence: rather than telling the story of his intellectual development chronologically, you have consecutively offered “prequels” and analyzed Foucault’s thought process by going backwards in time. To add to this unusual approach, the fourth volume in your series will cover Foucault’s work and intellectual development from The Birth of the Clinic (1963) to The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969), and thus sits between volume two and three of your series both thematically and chronologically. Why did you decide to hold this book on Foucault in the 1960s until now?

SE: Well it’s in large part because I didn’t intend to write all these books. I really did initially intend to write a single book for Polity – a history of the History of Sexuality was the initial idea. I had this thought of using the Collège de France courses to tell the story of how he’d initially planned the series and then what he ended up writing. I had an opening chapter on the first three Collège courses, as a kind of prelude to that study. But the manuscript as a whole grew, and the opening chapter split into two. Overall it was far too long. So, I discussed it with Polity and said I thought there were two options – either one, substantially longer book, or I take out the material in the opening chapters and develop that into a second book. After some discussion we went with the second option. Foucault’s Last Decade became the book on just that decade – 1974-84 – and Foucault: The Birth of Power on the immediately preceding period, roughly 1969-74 and the process that led to Discipline and Punish.

I then thought I would turn to other things, and indeed the next thing I did was to finish work on a book called Shakespearean Territories, which I’d been working on in parallel to this Foucault work – mainly in a series of lectures on different plays and their connection to territory. I had an idea that then I would write one more book on Foucault, the plan being it would be on the 1960s, and that these three books would cover Foucault’s career. But I remember clearly a conversation with Mark Kelly in Melbourne where I said that I’d be writing a book on Foucault in the 1960s, and Mark said: Foucault in the 1950s would be the really interesting book. My initial reaction was that it couldn’t be done – that there wasn’t nearly enough material to sustain a study of that period. But the more I thought about it, and the more the archives opened up, the more it became possible. I’m now nearly done with this work, and it’s actually been a case of more material than I can cover in the depth I’d like. There are some fascinating lectures and manuscripts, and some of the long-available sources seemed worth revisiting, especially Foucault’s work as a translator. And of course, shifting to the book on the 1950s has left a gap between this book and The Birth of Power.

So, the final book will be on the 1960s – the working title is The Archaeology of Foucault. The order I’ve written these books has been in large part a product of the availability of the material. When I began Foucault’s Last Decade they had published most of the mid-1970s and 1980s courses, and there were indicative dates for the remaining volumes. The courses from the early 1970s were some of the last to be published, in part because there were no tape recordings extant and so they had to use the course manuscripts. The papers left in Foucault’s apartment when he died were sold to the BnF in 2013, and have become available to researchers over the past several years. But the material on the early years is part of another collection of material, left in Foucault’s mother’s house, and that has been made available only recently. There isn’t an inventory of this material, so I worked through the boxes in sequence and there were lots of surprises. The courses and other manuscripts from the pre-Collège de France material are now being edited and published – one volume is out, and another should be out soon, though has been delayed by the current pandemic. So, my studies have been partly written in this order because of availability of sources. Until recently, there was very little material from the 1960s that hadn’t been published by Foucault himself. Now we have some courses from Clermont-Ferrand and Vincennes published, there are others in the archives being edited for publication from those places and Tunisia, there are drafts of books and so on. So, I now think the 1960s story can be retold in what I hope is an interesting and worthwhile way in the light of this material.

JK / AS: In The Birth of Power, you situate Foucault’s methodological development alongside his increasingly sophisticated theory on the relation between power and knowledge. Specifically, you argue that while established scholarship has long suggested that Foucault abandoned archaeology for genealogy as a method to “get at” power over the course of the 1970s, he actually thought of the two as distinct but not necessarily unrelated or contradictory approaches. Can you explain the difference between archaeology and genealogy in Foucault’s eyes and in how far he thought them complimentary? How does this revision help us see broader continuities in Foucault’s work?

SE: I think if we just read Foucault’s books the changes between them can seem quite abrupt. There is a quite dramatic change in content and style between History of Sexuality Volume I and then II and III, for example; or between The Archaeology of Knowledge and Discipline and Punish. I have sometimes started my books by marking what appears to be a stark discontinuity between Foucault’s books, and then tried to show how if we use other sources – shorter writings, interviews, lectures and so on – that we can see that there is actually quite a lot of continuity, or at least a much more gradual shift of focus.

I think the relation between archaeology and genealogy is one such apparent discontinuity, and it’s certainly true that Foucault doesn’t really use the term genealogy until the early 1970s. His essay ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’ is often seen as a key marker, though there are traces of this in his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France in 1970, and his first course there, Lectures on the Will to Know, from 1970-71. But for me at least, I think it makes sense to see that Foucault introduced this term genealogy to capture something which he felt archaeology did not, but as a supplement, an addition, a different perspective, not a wholesale replacement. I think it’s striking that initially on using the term Foucault’s isn’t absolutely wedded to it – he talks of a dynastics as a complementary approach, for example. And the genealogy he initially proposes is not of power, but of knowledge – it’s a new way to rethink the questions he was exploring just a few years before. Indeed, he talks of both a dynastic of forces and a dynastic of knowledge as an approach that develops from his work on archaeology. So, I think the archaeology of knowledge versus the genealogy of power contrast is overdrawn. Archaeology remains important to Foucault in later periods, and there are traces in his lectures but also in the different volumes of the History of Sexuality. And while power obviously becomes an explicit focus in the 1970s in a way it wasn’t before, this is hardly at the expense of an attention to the question of knowledge. So, some of the early secondary literature maybe drew too stark a contrast.

There is a moment in a discussion in Berkeley in the 1980s where Foucault says to his audience that he never stopped doing archaeologies, he never stopped doing genealogies. I think that’s broadly correct, though that doesn’t mean that he always meant the same thing or that there were no shifts. But I think the now available materials show that this is much more complicated and nuanced set of developments. I’m hardly alone in this way of reading him, but it seems to me that the material now published makes it hard to hold to crude periodisations of his work. I’m aware of a tension here, in that my works on Foucault have followed a broadly chronological order, that the splits between volumes have followed some of the traditional ones, and that one book is called The Birth of Power and another has the working title of The Archaeology of Foucault. I’d just say that lines need to be drawn somewhere given I’ve written several volumes, and that within these books there is an attempt to show the slow transitions rather than the abrupt ones. With Foucault’s Last Decade, for example, I was trying to show that the work of the 1980s was not some new, ‘ethical’ period, or a turn to antiquity, but that there was an important shared focus back into the mid-1970s and still earlier.

JK / AS: In Foucault’s Last Decade, you trace his intellectual activities from the day he started writing the first volume of the History of Sexuality in 1974 to his death in 1984, the year in which the second and third volumes of the History of Sexuality were published. Over the course of these ten years, Foucault abandoned his initial plan to write six volumes that would heavily draw from his lectures from the early to mid 1970s and directed increasing attention towards a hermeneutic of the self and ideas of governmentality. Yet, instead of emphasizing this abandonment of the original plan, you argue that long-standing interests of Foucault’s were combined with new insights and that his interest in the Christian practice of confession emerged as a major continuum. Can you elaborate on how exactly this interest in confession connects the work of Foucault from the early 1970s to his writings in the early 1980s, shortly before his death?

SE: It’s a long story and it’s really the puzzle that motivated the book I wrote. Early editions of Volume I announced the titles of the next five volumes, and there are indications in Volume I of how Foucault envisioned it would all fit together. The four constituent subjects of sexuality were the masturbating child, the perverse adult, the hysterical woman and the Malthusian couple, and Foucault anticipated books on all four. And there would be one on The Flesh and the Body as Volume II. To varying degrees, there are traces of work on each in the lecture courses, particularly The Abnormals, and Foucault talks a bit about these themes in the first volume and interviews around this time. Defert had been saying for years that the draft materials for these books had been completely destroyed. We now know that this isn’t entirely the case – while I don’t doubt some material was destroyed, there are sizable fragments of some of these volumes in the archive. These were not available when I wrote Foucault’s Last Decade, but there were some indications of what was there. So, I largely used the lecture courses to discuss this material. It seems Foucault drew on his drafts in preparing the lectures. I was intrigued by what Foucault intended to do, and then why it didn’t happen.

The second planned volume was this one on confession. And from the indications in the first volume, and in lectures at this time, it seems it was to be on the late Medieval church and particularly the Council of Trent. When did confession, especially but not exclusively about sexual desire, become such a focus? The longest discussion by Foucault in this period is in The Abnormals course. And it seems that The Flesh and the Body would have expanded that argument, obviously with a lot more historical and analytical detail. But as he says in various places, this argument didn’t work for him. He began to realize that the trends he was identifying around the sixteenth century could be traced back much further, and so he worked backwards historically to analyse this. I think the material on the Christian pastorate in the Security, Territory, Population course from 1977-78 is related to this reading back through the Christian tradition. And the discussion of the government of souls also relates to this focus. The most obviously Christian lecture course in Paris was On the Government of the Living from 1979-80. And it seems it was around that time that Foucault drafted a new study of Christianity for the History of Sexuality series, now under the title of Les aveux de la chair – confessions or avowals of the flesh.

JK / AS: In 2018, Les aveux de la chair was published as the fourth and final volume of the History of Sexuality series. In Foucault’s Last Decade, you speculated that this volume is “perhaps the key to the whole sexuality series” (133). Has this come true?

SE: Yes, I think it probably is the key. Although it has appeared as Volume IV, and that was the last place Foucault situated it in his plans, it was actually mostly written before volumes II and III. Foucault says that the text as initially written had a long Introduction on pagan antiquity as a prelude to the material on the early Church, but again that he was dissatisfied with it, and that he felt it made uncritical use of the secondary literature. So, he put the material to one side, and worked back through the earlier period himself. At one point Volumes II and III were a single volume, so in different plans what became Volume IV appears as Volume II or III. The first key indications of pagan antiquity in his teaching are in the 1980-81 course Subjectivity and Truth, but it becomes the major focus of all his remaining teaching. There are other, parallel and intersecting projects in this period too, and Foucault changes his mind about how to present the material – there are several, not always consistent reports that I try to disentangle. But I think a key focus is this question of confession – was it in the sixteenth century or earlier, and how did pagan sources anticipate or contrast with the early Church – that can be seen as at least one guiding thread. He then wrote a new introduction to Volume II which would stand as an Introduction to the three new volumes. That Introduction went through various versions, some of which are published, before taking on its final form in 1984.

Foucault was close to completing the work on Volume IV. Volumes II and III came out shortly before his June 1984 death. Earlier that year he’d anticipated Volume IV would be out in October. One thing I’ve learned in this work is that French publishing schedules, at least for Foucault, were much quicker than is usual now. He could deliver a final manuscript around four months before it appeared in the bookstores. Of course, his illness prevented him from working on this text as planned, and then he died before completing the work. But it was very close to being finished. However, I think Frédéric Gros has done a great job with editing the text. I worked with the manuscripts and typescripts of Volumes II and III, and I know how challenging this can be. Foucault’s handwriting is difficult, with even his own typists struggling at times, and there are multiple versions of chapters. So, I can imagine it was a challenge for Gros to work out what Foucault intended especially since his work had been interrupted.

Les aveux de la chair wasn’t available when I wrote Foucault’s Last Decade, and I was under the impression at that time that while it would be published, it might not be for some time. I thought they would publish the pre-Collège de France materials and that this book, the closest thing to a completed book by Foucault in the archives, would be the final text – the crowning glory as it were. At the time I finished Foucault’s Last Decade in 2015 it wasn’t available in the archives, at least not to me, but the manuscript and typescript have since become accessible. And as we now know, it was published in early 2018. I wrote a long review essay on the text very soon after it came out, as I was excited by the prospect and wanted to see how it delivered on the various promises Foucault made about it. I suppose that in time I might revisit Foucault’s Last Decade in order to take account of it. It would add a lot of detail though I don’t think it would radically change my overall argument of how it came to be written or how it fitted into the overall work in this decade.

***

This is the first installment of a two-part interview with Stuart Elden about his work on Michel Foucault. Continue reading here.

Jonas Knatz is a PhD Student in New York University’s History Department. He works on 20th century European intellectual history.

Anne Schult a PhD Candidate in New York University’s History Department. Her current research focuses on the intersection of migration, law, and demography in 20th-century Europe.

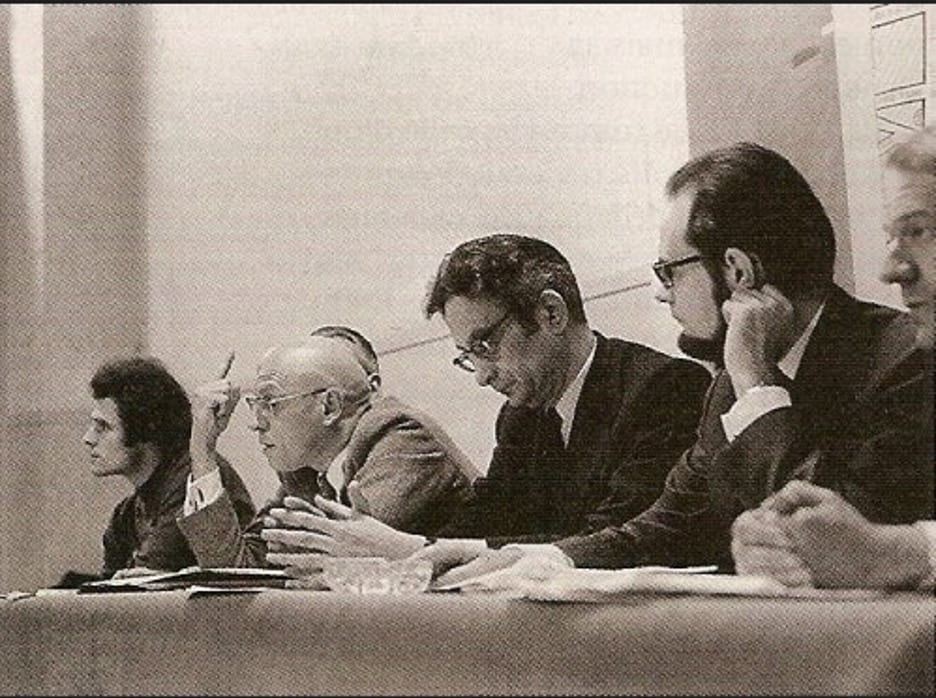

Featured Image: Press conference about the Jaubert Affair, 1971. From left to right: Pierre Laville, Michel Foucault, Claude Mauriac, Denis Langlois and Gilles Deleuze. WikiCommons.