By Enrique Ramirez

YOU ARE A VAPOUR TRAIL / IN A TV SKY

— RIDE, VAPOUR TRAIL (1990)

On a cool Spring night in 2014, driving on the Merritt Parkway through the heart of darkest Connecticut, I caught a strange noise through my speakers. It hung in the air inside my car for a couple of seconds before it broke apart into a field of high-pitched static. I detected within that jagged, dissonant burst some notes or chords from a pop song I knew from my youth. There was something else, however. As I focused on the red tail light contrails left behind by the cars and trucks speeding headlong into gloomily somber night, I thought I heard a voice caught in the hissing white noise. I could not understand what was being said, but the sound was unmistakably human, a symphony of glottal stops, fricatives, and sibilants. This voice crackled solemnly and distantly, broadcast from who knows when and where. I then took the nearest exit hoping to chase this human sound, to capture this fluttering pulse of life skipping along the aether.

The previous summer, on a rainy July evening in Chicago’s Union Park, I witnessed a charcoal-black raincloud descend from the sky as Björk took the stage at the Pitchfork Music Festival. I was far away, trying to cover my head as the ground below my feet became a swirl of mud and water. And through the haze, illuminated momentarily by the light emanating from the jumbotrons flanking each side of the stage, I caught a glimpse of the Icelandic singer. She entered in a field of magenta stars projected against three giant screens at the rear. Light glinted from her gold lamé dress. Quills emanated from her head—or at least that is what I thought I was seeing—turning her into a giant sea urchin save for a blank swath that revealed her mouth and face. She was not just from another world, but another world altogether, present, oceanic, suspended in the watery air enveloping the audience. There was a choir behind her, similarly dressed, all clad in platinum wigs, all dancing more or less together but not together, the movement of their arms and legs now appearing like strands of waterweeds carried along by sheets of rain. And then, that voice … so unmistakable. This was 2013.

*

It is 1897, and Albert Allis Hopkins, the future associate editor for Scientific American and a rabid Charles Dickens enthusiast, publishes Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, Including Trick Photography (1897), which contains a description of the backstage interiors of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. His point of view is that of the interloper, a person arriving upon the flotsam and jetsam of a previous evening’s reverie. His inventory of the items inside the “property-rooms” are matter-of-fact, but even the most casual reader may detect a hint of wanderlust in what at first seems to be mere description of objects from another time:

The property-rooms are the most interesting. Here you may see Siegfried’s Anvil, his forge, Wotan’s spear, the Lohengrin swan, or the “Rheingold;” while under the second fly gallery will be seen the parts of “fafner,” the dragon in “Siegfried,” […] the armory is a room containing a vast collection of helmets, casques, breastplates, swords, spears, lanterns, daggers, etc.; while in a case lighted by electricity are the splendid jewels, crowns, etc. which make such an effective appearance when seen on the stage. Here will also be found a model of the old dragon which was burned up in the fire. Hung up on one side of the wall is an elephant’s head with a trunk which is freely flexible, and in the next room will be found the head of a camel which winks his eyes. In here are also stored the shields and weapons which the great artists use when they impersonate northern gods and warriors. Under the property master’s charge are modeling rooms and carpenter shops. (265)

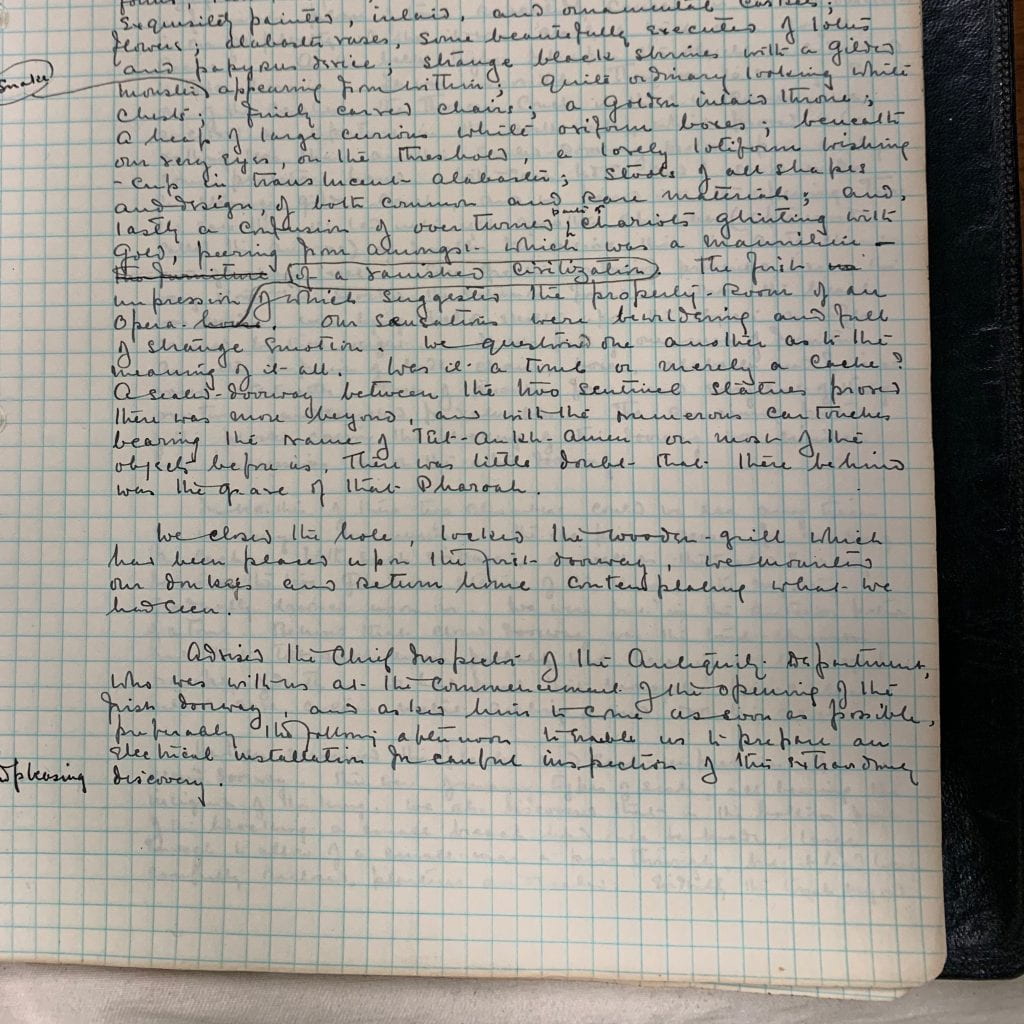

On November 26, 1922, Howard Carter descended by candlelight into an opening underneath the tomb complex of Rameses VI in the Theban Necropolis. He opened a door, which at least in his recollection, bore the “seal impressions of Tut.ankh.amen” when a current of hot air escaped and almost extinguished his candle. It was an exhalation, a release of pent-up memories of roiling sands, of waters diverting and scarring the Wadi bedrock, a remembrance of stars turning overhead in slowly changing patterns as armies ravaged the valleys and floodplains and made way for new patterns of living, for new forms of speech. It was this whoosh of air that whispered a lament for a burgeoning modernity and revealed to Carter a spectacle beyond his own imaginings. When he caught the first glimpses of “two strange ebony-black effigies of a King, gold sandalled, bearing staff and mace” looming out “from the cloak of darkness” and of “gilded couches in strange forms, lion-headed, Hathor-headed, and beast infernal,” Carter thought of the same world that confronted Hopkins in 1897. “The first impression,” wrote Carter of the gilded chairs, thrones, and chariots deep inside KV62, now known as the Tomb of Tutankhamun, “suggested the property-room of an opera of a vanquished civilization.”

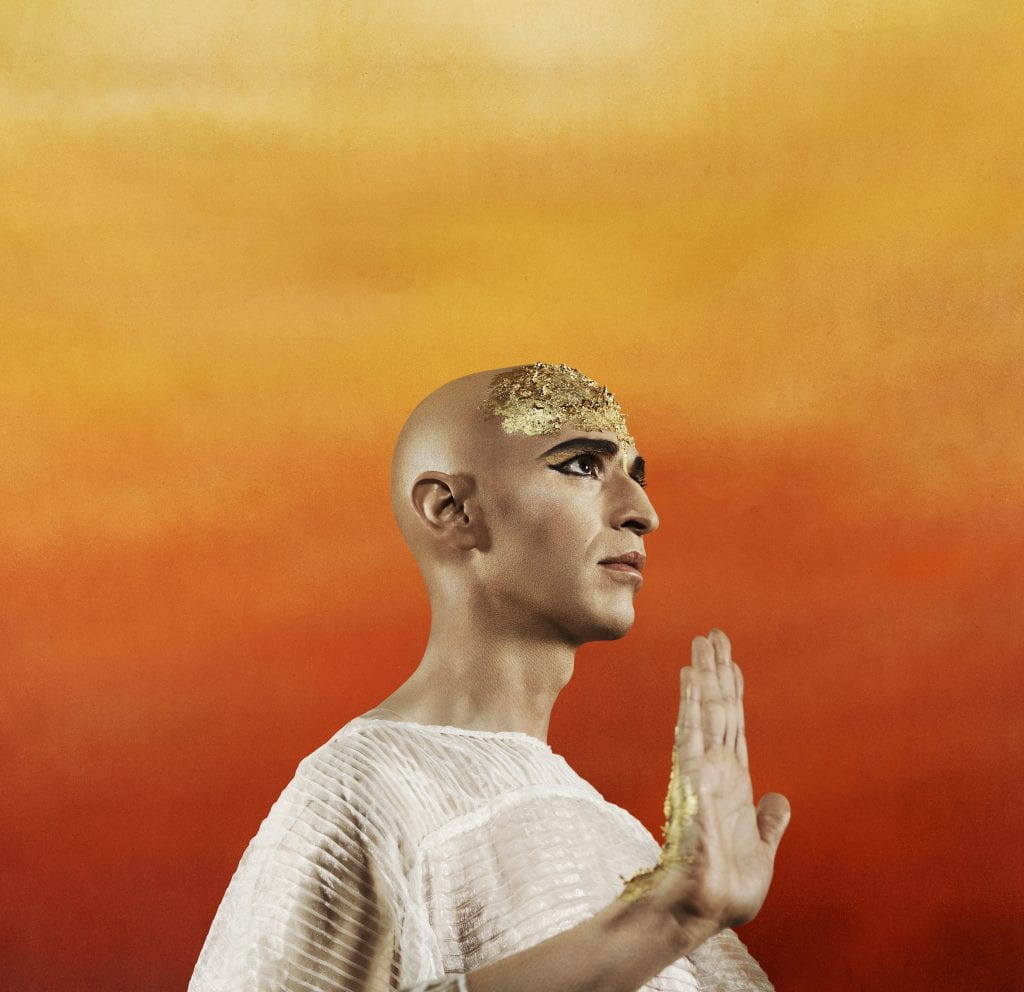

Nearly a hundred years later, in November 2019, I learned about Howard Carter’s discovery during a call with Anthony Roth Costanzo, who was just finishing a stellar run in the title role in the Metropolitan Opera’s performance of Philip Glass’s Akhnaten. To prepare for the role—a demanding one written specifically for a countertenor—Costanzo visited the Griffith Institute at Oxford University. It was there that he found Carter’s diary entry with its description of Tutankhamun’s tomb as a “property-room,” and his excitement at doing so was palpable, as if he were channeling the same thrill that Carter might have felt on that day in November 1922.

Perhaps this was because like Carter, Costanzo experienced the electric charge felt when one catches a glimpse from another world and time. I was reminded of Arlette Farge’s own account of an “impassive archivist” at the Archives Nationales in Paris, encountering her own property-room of sorts, a portal to another temporality. She noted: Time is elsewhere, as the clock has been still for a long time, like the one in the porphyry room of the Escorial where the kings and queens of Spain are buried, sternly laid out in their marble tombs. At the bottom of that dark Spanish valley the long line of the monarchy lies at rest; at the bottom of the Marais in Paris the traces of the past lie at rest. An analogy between the two mausoleums may seem arbitrary, yet on each of her visits to the inventory room she is struck by this memory from across the Pyrenees. For Costanzo, time too is sequestered in archives and rooms, in seemingly distant elsewheres, yet seamed together through the alchemy of his vocal performance.

Allow me to clarify. We talked of two Akhnatens. There is the first, successor to Amenhotep III and known for introducing a monotheistic cult at el-Amarna that replaced the worshiping of the falcon-headed sun god Ra with adulation for the solar Aten, the disk of the sun that appears to hover like a flying object before the new pharaoh. This is the Aknhaten committed to dusty archives and countless texts (including a novel by Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz). Then there is the Akhnaten of Glass’s work. This is Costanzo’s Aknhaten, with a libretto culled from a diverse array of texts and objects, from E. A. Wallis Budge’s translation of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, to the Pyramid Texts from the Old Kingdom, and even transcriptions of boundary stelae found in James Henry Breasted’s A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest (1906). This is more than singing, more than the mere enunciation of words written elsewhere. The artist momentarily inhabits a text and lives out its contours by summoning a “voice within a voice” (per novelist James McCourt), a voice that radiates and ensnares the audience in the feint of historical time.

“Opera time is slower than actual time.” This is Costanzo. In our interview, he is gregarious and friendly, knowledgeable not just about his craft, but also about Glass’s work. His performance at the Metropolitan Opera was not his first encounter with Akhnaten, having played the title role in earlier productions in London and in Los Angeles. I keep this in mind as he describes Glass as an “additive composer” that works with “macro structures,” clusters of time and sound that change ever so slightly to achieve maximum emotional impact. I cannot help but hear the voice of a historian in Costanzo. “The performer’s job is to create the narrative,” he tells me in our interview, as if echoing historian Carolyn Steedman, who remarked how the “practice of historical work, the uncovering of new facts, the endless reordering of the immense detail that makes the historian’s map of this past, performs this act of narrative destabilization on a daily basis.” (48) And Costanzo’s own descriptions of the structures of operatic time are reminiscent of Geoff Eley’s observation that Marc Bloch’s writings “freed historical perspective from simple narrative time, reattaching it to longer frames of structural duration.” (36)

This is not to say that performing historically is a kind of abstraction, a form of intellectual suspension that allows the musician to become lost in the structures and rituals of musicking. As it turns out, the craft of working within macro structures and of creating “longer frames of structural duration” is demanding—musically and physically. For instance, Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians (1974-76) is known as an exacting work. To borrow Costanzo’s own words about performing Akhnaten, it is “repetitive” and “relentless.” Music for 18 Musicians lasts about an hour when played live and is composed of 11 “pulses,” each a small piece of music based around a single chord. Different instruments phase in and out of the piece. In one moment, high-pitched female voices accentuate the downbeat. In another, bass clarinets enter with a low swell—a reedy doppler shift of sorts. The sonic complexity of Reich’s piece has a temporal effect as well. In Parallel Play (2009), music critic Tim Page cites his review of Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians as an important event that foreshadowed his eventual diagnosis with Asperger’s syndrome. Here, he remarks on the perception of time while listening to Music for 18 Musicians:

Minerva-like, the music springs to life fully formed—from dead silence to fever pitch. There is a strong feeling of ritual, a sense that on some subliminal plane the music has always been playing and that it will continue playing forever… imagine concentrating on a challenging modern painting that becomes just a little different every time you shift your attention from one detail to another. Or trying to impose a frame on a running river—making a finite, enclosed work of art yet leaving its kinetic quality unsullied, leaving it flowing freely on all sides. It has been done. Steve Reich has framed the river. (Tim Page 2009, 168)

This brings to light some similarities between Costanzo performing Akhnaten and musicians playing Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians. Both capitalize on extended temporal horizons, and both rely on a double commitment of sorts: there is the time depicted in the libretto and the score, and then there is the time required to perform it. One may even sense that the slight variations in key and fluctuating time signatures have been occurring in perpetuity. You have to wait patiently to experience the tonal changes, to feel the emotional shifts. You have to listen carefully for a similar sense of perpetuity in Music for 18 Musicians. Peel away the layers of voices, metallophones, and clarinets, and you will hear the constant and relentless pounding of marimbas and xylophones. Imagine how tired these performers must be. They have been playing for the past 56 minutes, but as Page noted, they could have been playing for an eternity. They could be playing the first sounds ever made.

*

“Everything made now is either a replica or a variant of something made a little time ago and so on back without break to the first morning of human time.” (2) It is 1962. This is George Kubler, writing in The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things. His eye is cinematic and roving, envisioning—literally—the history of art in terms of “form-classes,” each a sequence of objects whose differences are manifested slowly and deliberately in long, clustering durations of time. Beginning with a “prime object,” they vary and develop across different materialities, becoming the aforementioned replicas, and in some instances, developing mutations. The routes of Kubler’s “form-classes” are registered as if in a chronophotograph or stroboscopic flash photo: a gauzy presence that makes itself known persistently. I hesitate to call these developing forms phantoms, if only because Kubler reserves this ghostly description for a category of objects that exists outside the contours of his temporal purview. These are fashions, objects marked by “duration without substantial change: an apparition, a flicker, forgotten with the sounds of the seasons.”

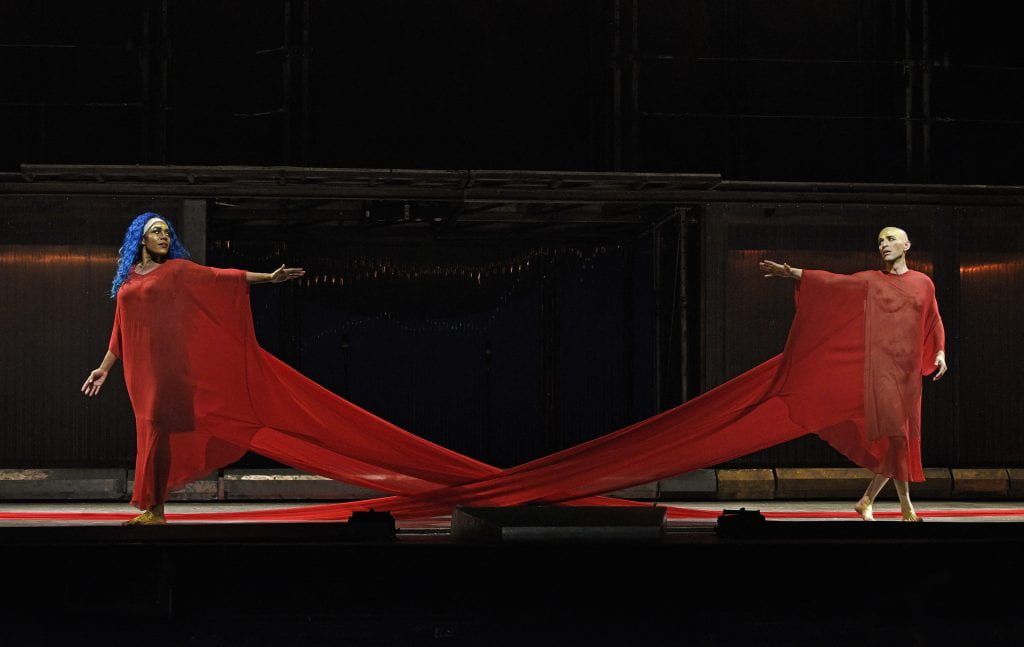

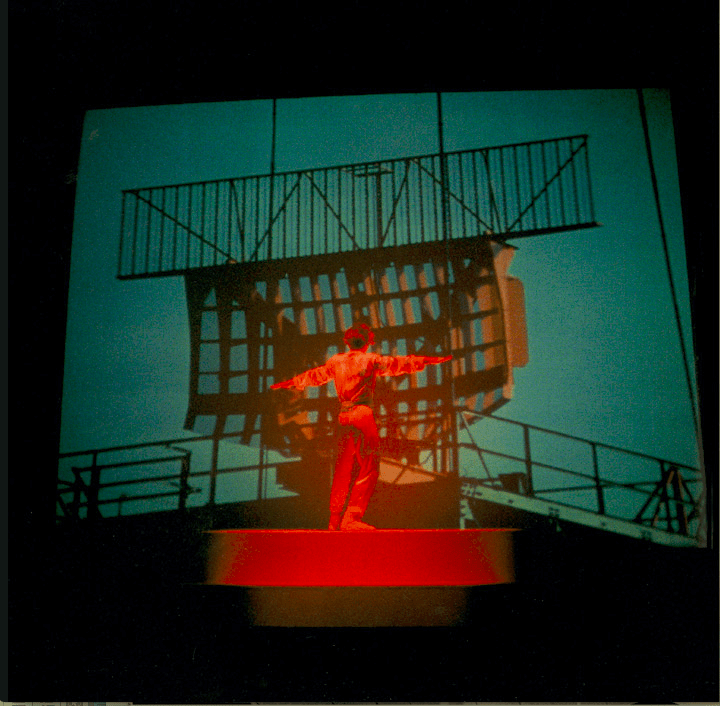

The twin serpents once wound into a diadem encircling Akhnaten’s head are gone. In its place, a toy doll’s face peers from the front of a Deshret, the Crown of Lower Egypt. Above, a Hedjet, the White Crown of Upper Egypt, receives an egg-shaped stone of veined carnelian, polished and shining. Combined, the two crowns rest on top of a headpiece resembling a Nemes, a simple headdress, and here made of EVA foam and shellacked to look like an ormolu casque. Around the pharaoh’s face, blue, red, and green plastic jewels echo the bands of amazonita, turquoise, feldspar, and obsidian found on the funerary mask of Tutankhamun. And the effect is similar. They splinter light in all directions and for a moment, the audience may be lost in what looks like a radiant crown hovering around Akhnaten’s head. On the neck, aligned with the chin, a giant gold brooch appears suspended between lines of pearls fastened to an oversized pauldron on each shoulder. They are covered with more clusters of doll faces. Some of them are ashen, with lips and eye sockets dabbed in lampblack. Others are simply burnt, covered in dark alligator-skin blotches or bubbling blisters from which dead eyes peer at the audience. A v-shaped bodice shrouds the pharaoh’s torso in cascades of gilded crinoline and tulle. It flares out to create a large split skirt with a lower hem made of turquoise ruffs and more doll faces. Seen from the front, the pharaoh cuts a wide figure, part-Kamakura era Samurai, part-Elizabeth I posing for her Spanish Armada portrait. Flanked by Horenhab and the High Priest Aye, Akhnaten holds a crook and flail, confident in his newfound authority. When he is on the stage performing and in this costume, Costanzo is in Akhnaten’s body. This is what he tells me.

A historical figure, like a fictional character, defies death by living across various texts, in different media. It is “a stand against oblivion and despair,” as Ian McEwan tells us in the final moments of his 2001 novel, Atonement. Whether in the guise of a novelist or under the mantle of the seasoned historian, a writer conjures an immortal subject, and does so in multiplicities. The historical Akhnaten and the operatic Akhnaten can exist in the same place and at the same time. So does Helen of Sparta, whose sequestration becomes the flashpoint of a conflagration, a tale of killing fields and captive voices woven into an everlasting refrain born of war and anguish: “Sing, Goddess …” I think of the image of Helen, her eidolon appearing not just in different texts, but in different places. In addition to the Helen in Homer, there is also the Helen in Herodotus and the Helen in Euripides (as well as the Helen in recent novels like Madeline Miller’s Circe and Pat Booker’s The Silence of the Girls.) Helen narrates her own fate, of the Judgment of Paris, and speaks through Euripides: “But Hera, indignant at not defeating the goddesses, made an airy nothing of my marriage with Paris; she gave to the son of king Priam not me, but an image, alive and breathing, that she fashioned out of the sky and made to look like me.” The image of Helen is substantiated not because it looks like her, but because she breathes, and by implication sounds like Helen. She speaks. She laments. She sings. Helen is telepresent. Helen is theatrical. She is more than a trompe l’oeil. She is a trompe l’oreille.

I heard Helen in 2013, listening to the Buggles’ 1979 hit “Video Killed The Radio Star” on a pair of studio monitors. I closed my eyes and heard her in the background. At first the voice was slow, languorous (not the one that goes “Oh-a Oh”). It was almost lost among the sequenced drums and ARP String Ensemble swells, and monophonic Minimoog and Prophet 5 voicings. During the second verse, when bassist Trevor Horn sings, “And now we meet in an abandoned studio/We hear the playback and it seems so long ago/And you remember the jingles used to go,” Helen’s voice stays in the background until the end of the verse when it transforms into a high-pitched scramble as her recorded voice rewinds at high speed. And finally, as the song reaches its coda, I hear Helen singing “You are a radio star,” only getting louder, panning subtly from back to front, changing from mono to stereo.

t is 1987. I hear Helen in Laurie Anderson’s “Blue Lagoon,” a track from the 1984 album Mister Heartbreak. She is marooned on an island, reciting a letter to a distant love as if she were Miranda from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. She addresses her rambles to a digitized male voice skipping above a wobbling synth. The effect is disorienting, and as we listen to Anderson’s voice, hers is one of resignation turned to sarcasm: “Days, I dive by the wreck. Nights, I swim in the blue lagoon / Always used to wonder who I’d bring to a desert island.” Her letter quickly becomes an interior monologue, oneiric musings to the disembodied, electronic voice that sounds almost like the Ariel-like Robby the Robot from Forbidden Planet (1958). She recites Ariel’s song from Act I, Scene II of The Tempest (“Full fathom five thy father lies / Of his bones are coral made”) before riffing on the Epilogue from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, just as the accompanying, irregular rhythms and guitar feedback samples become a swelling chorus of gamelan instruments and steel drums, increasing in volume, as if the song were levitating, invoking a moment when Ferdinand hears Ariel’s singing and asks, “Where should this music be? I’ the air or the earth?”

*

I have heard voices. They are the sounds of ethereal presences eulogized into printed words, relayed station to station. They are compressed vibrations, airborne, wired and ducted into our cochlear nerves. They mimic speech. They are unmoored in time and space. They scatter across electromagnetic spectra, twisted into technicolor coils of visible wavelengths. They fray and recombine once again as dense fabrics of pixels emanating a ghostly haze of narrow-spectrum blue light. These are the voices I have heard.

MALDEN BRIDGE, NY / BROOKLYN, NY

NOVEMBER 2019-MARCH 2020

Enrique Ramirez is a Brooklyn-based writer, architectural historian, musician, and critic. He is currently a critic in graphic design at Yale School of Art. You can follow him on instagram at @riqueramirez

Featured Image: Costanzo. Ascent.