By Nuala Caomhánach and Jonathon Catlin

Text

From May 8–9, 2020, thirty leading historians of medicine presented in the virtual webinar “Pandemic, Creating a Usable Past: Epidemic History, COVID-19, and the Future of Health,” sponsored by the American Association for the History of Medicine and Princeton University’s Department of History. Keith Wailoo, a historian of medicine and Chair of Princeton’s Department of History, opened the event by noting that while there has been much talk of the unprecedented nature of Covid-19 in popular media, for many historians this epidemic seems remarkably familiar. Participants presented on diverse aspects of pandemics past and present, including differential health outcomes for particular groups, literary depictions of disease, the history of social distancing, the invention of public health, different concepts of political and medical “success,” and asking how to locate the moments of when and for whom a pandemic is declared over. They were joined by over one thousand guests, who posed questions digitally.

Explaining Epidemics: The Past in the Present

Presentations began with remarks by Charles Rosenberg (Harvard), whose influential article “What Is an Epidemic? AIDS in Historical Perspective” (1989) argued that epidemics are social “events” with “a dramaturgic form”; they elicit “immediate and widespread response,” unlike other slow trends to be retroactively excavated by historians. Drawing upon his reading of Albert Camus’s 1947 novel The Plague, Rosenberg wrote, epidemics “follow a plot line of increasing and revelatory tension, move to a crisis of individual and collective character” that mobilizes “communities to act out proprietory rituals that incorporate and reaffirm fundamental social values and modes of understanding.” In his remarks, Rosenberg said that differing symptoms and lethality of various infectious diseases shape the social impacts that turn them into “phenomena” or historical “events.” AIDS, for example, was “surreptitious and idiosyncratic,” a slow-moving disease that was at first difficult to detect, while cholera was the opposite, a disease with “melodramatic” symptoms that could be fatal within hours of infection. Hence certain outbreaks like cholera become events—“a signal”—while other diseases like tuberculosis that killed many more people often remained “background noise” that he likened to auto fatalities today. Dramatic epidemics like cholera “questioned society in every dimension” and led to discussions about the appropriate role of the medical professionals, individuals, and governments.

Speakers identified the 1832 cholera epidemic as a social and political turning point in the rise of modern public health. Keith Wailoo said that there was a pervasive sense that this so-called “Asiatic” cholera wouldn’t affect Europe or North America; but when it did, it underlined existing bemoaned social conditions including poverty, filth, and “intemperance.” Wailoo saw echoes of this in the present, in what he called the “magical thinking” of “it’s not going to affect us,” the illusion that disease will not affect one region or group for one reason or another, for example the governors of rural states in America saying “we’re not New York,” and then waking up to an outbreak. Rosenberg noted that such popular cultural views played an important role in the early stages of the AIDS epidemic, when it was considered a “gay disease” and elicited attitudes toward urbanism, gender, and sexual behaviors. It also activated religious views about transgressing god like cholera had in the nineteenth century. He criticized the pattern he called, “it’s them, not me,” be it “because they’re dirty or lazy or Roman Catholic in 1832 or gay or Haitian in 1984.” “Change is hard,” he reflected. Wailoo similarly criticized a tendency to blame sick groups for their own illnesses; often this included the poor, but also particular ethnic groups, like Irish Catholics in New York’s 1832 epidemic, “identifying people who were already stigmatized and available for different kinds of scapegoating.”

Nancy Tomes (Stony Brook) said that historians frame diseases based on their exposure to past ones, and she lamented the fact that many in the media today don’t even have lessons and patterns from the HIV/AIDS epidemic in mind. She apologized for her remarks veering toward the “dystopian end of the spectrum.” Outbreaks of disease, she said, often function as “great revealers,” of social problems that have gone unaddressed. “That’s not news!” she said: Historians have identified this pattern “over and over again.” Yet seemingly just as often as lessons are learned, they are unlearned or forgotten. Her book The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life (Harvard, 1998) she said, asks, “How do you live your life when germs are everywhere?” She focused on the “Spanish” flu pandemic of 1918, which was used to develop a plan for pandemic preparedness, though these plans “sat on the shelf” until today. Tomes said historians could contribute to a “balancing” of public perspectives. Public health spending never recovered from the 2008 recession, she said, so things were already going in the wrong direction, and historians could call attention to the consequences of this.

All three speakers emphasized that pandemics bring out existing social problems that have been ignored, swept under the rug, or pose uncomfortable choices. Rosenberg noted that structural racism and inequality had become talking points in recent years but have been acted out during the pandemic in egregious and didactic ways. Pandemics, he said, place a “stress test” on governments to respond. Wailoo noted that analogies to past pandemics also raise the question of what kind of leadership is desired or required in such urgent moments. Andrew Jackson was seen to flop in the 1832 cholera epidemic. Herbert Hoover did the same in the great depression and did not rise to the occasion, but he did lead to someone who could, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who has recently been invoked as an analogous leader to Andrew Cuomo. While “we don’t get to choose our leaders” when pandemics arise, their choices greatly affect health outcomes.

Rosenberg noted that public hospitals originated in alms houses, which, then as now, were usually underfunded, crowded with a diversity of people, and bore a dramatic burden during an epidemic. He referred to this “socio-structural” dynamic of stigmatizing affected and usually under-resourced groups as an “original sin.” Pointing to the devastating health consequences of Hurricane Katrina, he called this the “who knew phenomenon—who knew we had poverty?”

Rosenberg also identified another less predictable didactic moment in the pandemic: the dehumanizing process of how we get modern packaged meat. We realized, he said, that “this inexpensive product has costs that nobody had thought about.” He likened recent revelations to Upton Sinclair’s 1905 novel The Jungle. He also cautioned against over-dependence on vaccines as a cure, noting that we still don’t have one for AIDS, a virus he said revealed overconfidence and scientific exceptionalism about infectious diseases from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Both Rosenberg and Tomes stressed that government response can make a dramatic difference. In Germany, Rosenberg noted, Chancellor Angele Merkel has a Ph.D. in chemistry, which has no doubt affected her tendency to rely on experts in shaping public health policy. Tomes argued that the term “pandemic” is defined not by the sheer number of cases, but by the extent of geographical spread. We’re more likely to use the term “pandemic” now, she said, because we realize and conceptualize the global interdependency of our world, which was already there at the time of the bubonic plague and cholera but is now palpable thanks to the media.

Wailoo praised Tomes’s work on how urban pandemics illuminate “the present state of society,” and how disease can be said to offer an immediate“judgment” on a way of life. Tomes responded that pandemics raise the question, “Who is the ‘we’ in a nation? Who is worth protecting?” These “stress tests,” she said, often reveal which inequalities can be tolerated, resisted, or overcome. Nations’ responses reflect those kinds of beliefs, values, and accommodations. In closing, Wailoo admitted that understanding underlying issues historically is not itself a solution to them, but hoped that recognizing patterns might help us ask more meaningful questions about what could happen next and what kind of society will come out the other side of the crisis.

Epidemics and Urban Centers: Different Cities, Disparate Experiences

Howard Markel (Michigan) offered a brief history of the term “social distancing,” which began to take root around 2005 amidst worries about Avian Flu. While this disease turned out to have limited impact on human beings, a closer analogy to Covid-19 is the flu epidemic of 1918–19. He called it “the worst case scenario” and hence one of the best cases for data collection since the birth of modern germ theory: 10–14 million cases and about 675,000 deaths in the U.S. and at least 50 million deaths worldwide. Around 2005, Markel was called upon by the Pentagon for his experience with “protective sequestration,” or social distancing, which they wanted to apply to defense workers, though the plans were not adopted. A key insight of 1918, he said, is that 23 out of 27 cities he studied had double-humped infection curves, indicating that they likely “released the brakes too early.” Since no city had a second spike while social restrictions were still in place, he concluded that this showed that there was probably a causal relation between such protections resulting in lower cases. Societies in 1918 were also generally more accustomed to outbreaks; roughly 1 out of 5 babies died before their first birthday from infectious diseases.

Evelynn Hammonds (Harvard) unpacked ways that native and black populations in America have been disproportionately affected by the virus. She was surprised and disappointed to hear leaders like Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzger admit that racial disparities were a serious concern but also claim that governments couldn’t do much to address decades of health disparities in the relatively short timeframe of the crisis. For Hammonds, such comments recalled a 2000 hearing before the U.S. Senate on health disparities called “Bridging the Gap,” which had identified long-term policies that might have lessened the blow of Covid-19 on minority populations.

Kavita Sivaramakrishnan (Columbia) focused on another at-risk group, “fugitive” populations of migrants produced by post-industrial shantytowns and slums, especially in South Asia. She said that the crisis only exacerbated existing precarities and that poor working conditions themselves need to be changed. She called for “reinventing poverty.” While the condition of slums often gets normalized, she said, in times of crisis it needs to be justified. Referring to “fugitive” laborers who often perform “essential” work that sustains the urban middle classes but themselves live in slums, she asked, “Why are these people still invisible?”

Gregg Mitman (Wisconsin–Madison) spoke on the 2014–15 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and noted that it took about six months for the international community to respond and the World Health Organization to sound the international alarm. The disease itself was very deadly but not nearly as contagious as Covid-19. The total numbers of cases reached about 11,000, but the outbreak was still portrayed as a global health crisis. He noted the irony that some of the same criticisms of African countries made at the time, such as disbelief, fear, conspiracy theories, and rumors, are now playing out in the U.S. regarding Covid-19, though they are driven by different economic and social motives. In many ways, he said, the response of the U.S resembles that of a failed state, the same charge applied to West African nations fighting ebola. He said we might learn from their experience: many African nations are used to “living with viruses” rather than merely “containing them.” Since coronavirus has mostly impacted Europe and North America, he saw a “reverse directionality at play,” with African nations banning travel from the U.S., challenging the stereotype of Africa as a diseased continent.

In the discussion, Hammonds noted ways that poverty had been rendered “invisible” until the coronavirus crisis. Notably, most people do not see the close working conditions of “essential” workers who are now at risk. Stay-at-home orders pose new challenges because it is often impossible for impoverished and vulnerable groups to engage in social distancing, for example by providing space for children to do their schoolwork at home. Markel similarly noted that in the 1918 pandemic some Chicago officials were reluctant to close schools because they knew that children who were homeless or living in tenements would be safer in school, protected from abuse and street violence. During this pandemic, it has become clear how many children rely on free breakfasts and lunch for nutrition, and some cities now provide them at pickup sites.

Panelists also addressed backlash, riots, and violence that have resulted from past containment measures, for example in outbreaks of cholera in New York City in the 1890s and in Italy in 1911. Protests emerged in response to both inadequacy of government and curtailing civil liberties. Yet Markel argued that the term “lockdown” is not accurate today, as long as there are no guards keeping people inside. He said one of the best ways to convince people to follow public health guidelines is to suffuse them with patriotism. During World War I, for example, “do your part” posters created by the Red Cross celebrated helping contain the flu and contributing to the war effort, while the term “slacker” was applied to condemn those who did neither.

The panel concluded with a number of concrete takeaways. Hammonds said that historians could help actively dispel rumors. Mitman advised against exoticizing wet markets and eating wildlife when many Westerners do the same. He also advised that scholars can help archive the present crisis, as his collaborators have done using social media to record social experiences of ebola. Sivaramakrishnan urged that historians should not only be public intellectuals but also activists. Markel noted that during World War I, pandemic teams of medical students and practitioners from leading medical schools were called into duty at home and overseas. Finally, Markel said, connectivity can help educate the public through commentary and pandemic curricula.

Epidemic Responses: Civil Liberties and Public Health Politics

David S. Barnes (Penn) spoke on “Lessons from the Lazaretto,” the first quarantine hospital built in the U.S. in Philadelphia in 1799. He praised its leaders for walking a tightrope between managing disease and managing social backlash and attributed this to the following qualities: being honest and not soft-pedaling bad news to leaders, being flexible in quarantine regulations, and making affected parties feel their concerns were heard. He also noted that in Philadelphia’s past, pandemic-related restrictions have been criticized as a means of voter suppression.

Richard Mizelle (Houston) spoke on “Black Lives in the Wake of Calamity,” noting that nursing homes were also sites of crisis during Hurricane Katrina. He asked how we think about and visualize this disaster: Is it a ball-like virus with spikes coming out of it or graphic images, like those associated with Katrina, of dead bodies floating down the street? In some cities during the 1655–66 bubonic plague, for example, church bells chimed every time someone died. He argued that our view of a disaster should be broadened to include the total number of deaths in a crisis period. Regarding Katrina, Mizelle’s research discusses indirect deaths resulting from problems including routine illnesses and lacking basic supplies like food and insulin. The historian Scott Knowles, host of “COVID-Calls,” makes a similar case in his 2018 essay, “What Trump Doesn’t Get About Disasters,” which argues that including indirect deaths after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico that were not counted in official records raises the death count of that event from 6–18 to about 3,000. “Poverty,” reads Knowles’s tagline, “is the slowest disaster.”

Panelists also discussed the issue of visibility. In the past, having a poc-marked face was a sign of health because it indicated your immunity to smallpox, while in 19th-century New Orleans surviving yellow fever similarly conveyed increased status. The problem of these approaches is that people have in the past become deliberately infected, a worry again today as individuals may seek to get infected to acquire so-called “immunity passports.” Moderator Raúl Necochea (UNC Chapel Hill) recalled living through the 1991 cholera epidemic in Peru, and noted that while it now seems a successful public health response in retrospect, at the time it felt like chaos.

Uncertain Knowledge in Epidemics: How Crises Spur New Therapies, Surveillance Practices, and Dubious Theories

Mariola Espinosa (Iowa) asked, who are the invisible bodies that are not being counted? She noted a recent remark from the chief justice of Wisconsin’s Supreme Court that distinguished the predominantly immigrant workers in meat-packing plants from “regular folks,” a comment that seemed to lay bare the differing values placed on the health of various social groups.

Emily Waples (Hiram College) described differential reactions to the cholera epidemic of 1832: Whereas Europeans tended to centralize control and response, Americans doubled down on individualism, linking the disease to intemperance and failures of self-control, and accusing groups of bringing cholera upon themselves. Again today, she noted, success of treatment depends on the diagnostic awareness of individuals upon their own health and symptoms.

Graham Mooney (Johns Hopkins) discussed John Stuart Mill’s harm reduction principle, which holds that the only purpose for which power can be exercised over a community is preventing harm to others. This framework sets individual rights against the safety of everyone else. He also noted that privacy concerns about tracking coronavirus are not new: At the birth of public health, people usually died at home, so the state wanted access to what happened inside peoples’ homes. He also discussed the problem of conspiracy theories, but said that while they should not be believed it is important to ask, “Why are they believable? Why do people need them?” Conspiracy theories like those during times of cholera suggesting the disease was introduced to kill off the poor spoke to underlying class tensions and poverty that outbreaks inflamed.

After Epidemics: The Challenge of Reinventing Public Health

The final panel offered much intellectual food for thought. Wailoo opened the panel by explaining how diseases such as polio, AIDS, and cholera challenge the notion of humanity controlling nature, and force us to reconsider public health on the local, national, and global scale. Anne-Emanuelle Birn (Toronto) situated the global medical issues facing humanity within the framework of existing national borders and public health policy. In what ways, she asked, has the coronavirus revealed the pores and weak links in the chains across trade, international quarantine and disease surveillance, and the role and responsibilities of international health organizations, such as the WHO?

Dora Vargha (Exeter) addressed the concept of success: What constitutes success in a pandemic, who gets to decide when the pandemic is over, and what does the aftermath look like? Does success center on finding a vaccine or healing the final disease-positive patient? Do medical scientists and politicians view the concept through different lenses, and what is the impact and outcome of such definitions? Is halting the progress of the pandemic the final narrative defining success? As Akwasi Kwarteng Amoako-Gyampah, Nancy Tomes, and Birn engaged this simple, albeit provocative question, the panel addressed the complex and diverging reinventions of public health policy and programs within different countries, which can lead to misinformation and different definitions of diseases and cures. This left the panelists grappling with how we define global public health as historians and the role of history in aiding in public policy.

Nuala Caomhánach is a Ph.D. Student in New York University’s History Department. She works on 19th and 20th century History of Science and Environmental History.

Jonathon Catlin is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM) at Princeton University. His dissertation is a conceptual history of “catastrophe” in modern European thought.

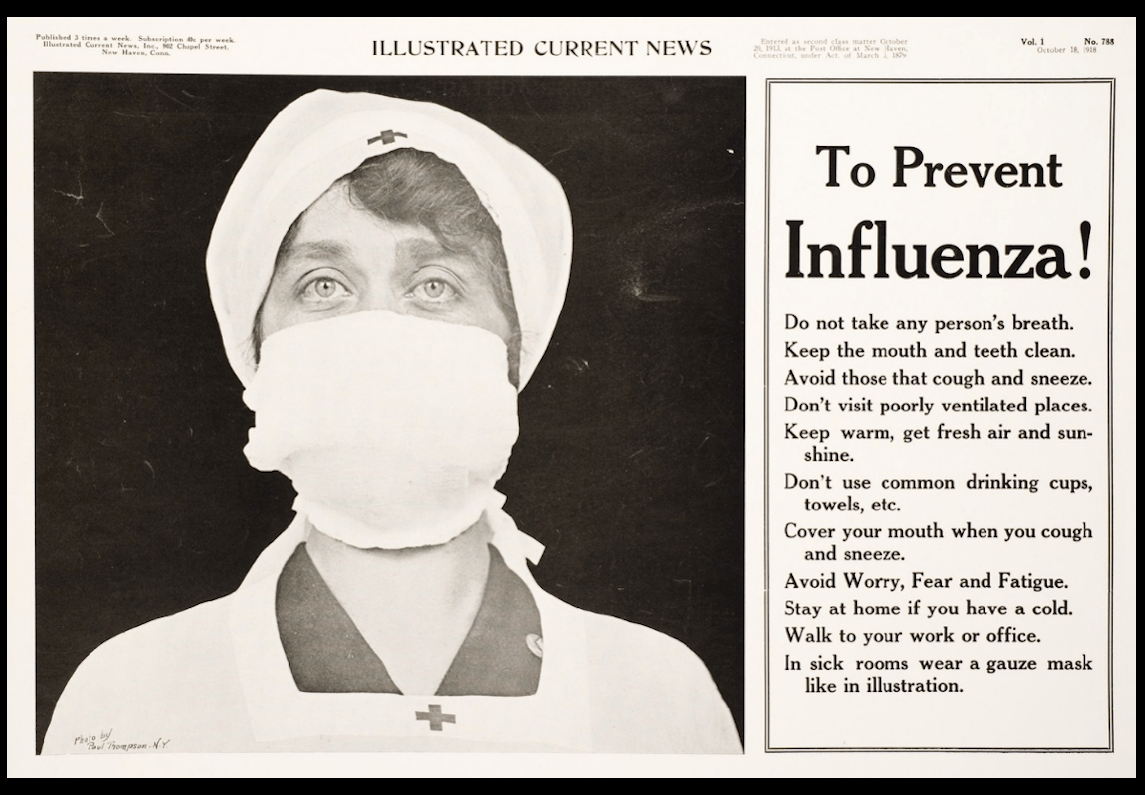

Featured Image: “From the October 18, 1918 edition of the Illustrated Current News in New Haven, CT”, Paul Thomson photographer. Included in the conference poster.