By Saara Penttinen

This blog post was supposed to be about something else.

Being inspired by the ongoing coronavirus situation is not something I expected or wished to happen. In fact, I feel conflicted about even admitting it despite many rather stimulating articles written in apparent lighting speed exploring, for example, epidemics and plagues in history, sprouting up in recent weeks. There might never be a return back to ‘normal’ – everything might have changed before we got a chance to say good-bye. There’s nothing else to do except to adapt, as people have done countless of times in history. I haven’t been able to write in about a month, but today I felt it was the time. Perhaps this is me, adapting.

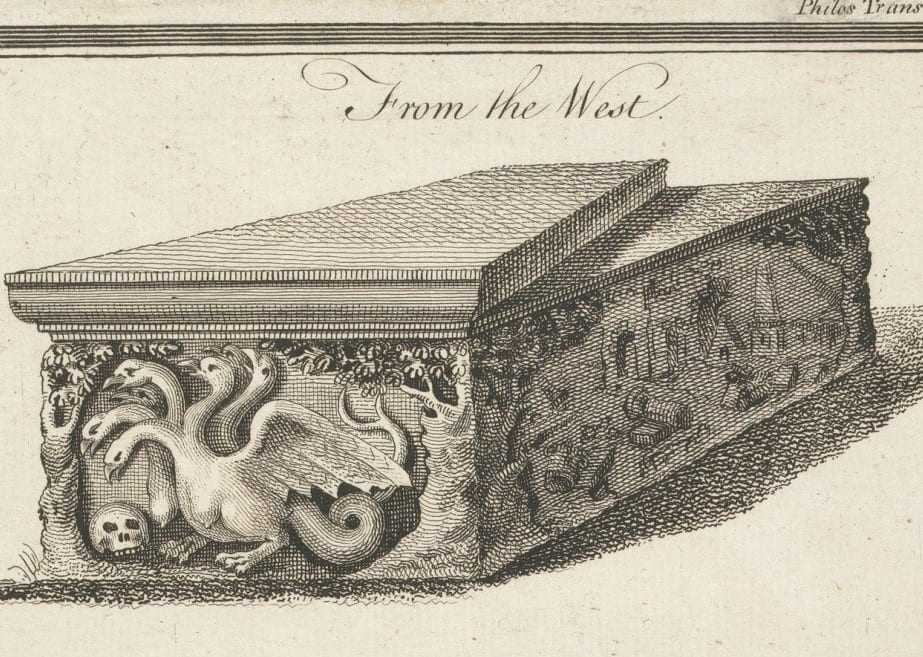

Nevertheless, I’ve had some difficulties in centering my scattered thoughts, especially since the focus of this text has changed so drastically. But I want to start from the beginning: in the original marble lid of the famous Tradescant tomb in Lambeth. Since the early modern collections commonly known as cabinets of curiosity became a popular research subject in the last decades of the 20th century, the inscription – dedicated to father and son John Tradescant, eager seventeenth-century curiosity collectors – has been quoted in numerous publications The most quoted lines go as follows:

By their choice collection may appear

Of what is rare, in land, in seas, and air:

Whilst they (as HOMER’s Iliad in a nut)

A world of wonders in one closet shut.

Especially the last line describing the Tradescant collection, aptly called The Ark, as “a world of wonders in one closet shut” has been perceived to sum up nicely the microcosmic nature of these collections; in other words, they were understood as worlds in a miniature form. But how exactly were they ‘worlds’? What was their relationship with the wider world, the macrocosm? Were they considered substitutions of the real thing, simulations, or worlds in themselves? Since asking these questions in the beginning of my PhD studies, I have fallen deeper and deeper into the abyss of early modern ambiguities and analogies. Especially one of my key concepts seems to evade me. This concept is virtuality.

Virtuality is one of those terms that gets thrown around a lot nowadays – I mean a lot. It has been used so much especially since the beginning of the internet age that it has lost its novelty and started to appear commonplace, even mundane. Despite its popularity, virtuality as a concept is more often than not taken for granted and not actually understood very well. What does virtuality, in fact, mean?

Nowadays everything seems to be virtual from shopping and entertainment to therapists, maps and communities. Through a huge array of avatars on different social platforms also our social lives and most intimate communications are, at least partially, virtual. But this was the situation only in February – it is nothing compared with were we are right now. If there ever was a time for virtuality, that time is undoubtedly now. How to be present without being present – that is the question on everyone’s lips. How to work, or go to school? How to visit elderly relatives? How to stay sane, or to feel connected with the world, even just a little bit? How to substitute the experiences that were taken away from us? Is it okay to drink a bottle of wine alone, if you’re doing it on Zoom?

Virtuality as a term holds many futuristic connotations, even if the future seems, to some extent, to be already here. The virtual future might mean an era of connectivity, shared experiences, and democratic opportunities. It can also mean a time of blurred lines between right and wrong and losing the touch of reality. Though many things are arguably gained in the current dystopia, many are also lost, perhaps for good. Besides the devastating human and economic cost, some of the loss happens in the very translation of the actual to the virtual, never to be recovered again.

Despite the futuristic connotations, and the contemporary usage of the term, virtuality has a history just like everything else. The first associations for most people are the different technologies, such as virtual memory, simulations, and virtual realities. The history of virtual reality is usually stated to have started in the 1930s, sometimes with a mention of earlier technologies, such as 19th-century stereoscopes and panoramas. The main function of virtual reality technologies seems to be in creating a sensory immersion of a kind – essentially, in fooling the eye and sometimes other senses too to feel like the experience is taking place somewhere completely different. Oliver Grau’s 2003 book Virtual Art takes a media history’s point of view and traces the history of illusory techniques in art from modern days all the way to Antiquity. My own research period, the seventeenth century, had a huge array of ‘virtual art’ alongside a multitude of devices for creating spatial and optical illusions. In general, the early modern period can be described as an era of un utmost interest in modifying the sensory experience.

Nevertheless, virtuality doesn’t only entail technologies, devices, or even illusory techniques. What’s the thread holding it all together – what’s the essence of virtuality itself? Alongside the computer-related meanings, the modern-day definition of virtuality according to a (virtual) dictionary is “in effect or essence, if not in fact or reality; imitated, simulated” while actual is “existing in act or reality, not just potentially”. Therefore, the term could be used in context of something being ‘as good as’ something else – as can be perceived in the everyday use of the adverb virtually.

The etymology of virtual most likely originates from Medieval Latin’s virtualis derived from the notoriously equivocal Latin word virtus, meaning for example, ‘excellence, potency, efficacy’. In a late 14th-century meaning, virtual meant something in the lines of “influencing by physical virtues or capabilities, effective with respect to inherent natural qualities.” In the beginning of the 15th century, this had been concentrated to the modern meaning: “capable of producing a certain effect”, and therefore, “being something in essence or effect, though not actually or in fact”.

Virtual travel is a concept that instantaneously comes to mind when thinking of substituting the real thing with something ‘as good as’. For most seventeenth-century people, travelling virtually was the only way to see the world. Most classes, professions, and age groups rarely travelled. Religions and customs often frowned upon the concept of ‘worldliness’, and people were suspicious about wanderers and rootless people. Even those that were able to travel, usually only got to do one big journey in their lifetimes – such experiences were cherished and relived, and eventually turned into travel writings, plays, and collections for other people’s armchair travel. Experience didn’t necessarily have to be direct; even an ad vivum picture could be made by an artist only consulting a previous representation of the subject.

Before March, I had no idea I wanted to travel (or at least, to wander aimlessly through hardware stores) as much as I do now. A couple of weeks ago, at the pajamas stage of the pandemic, I witnessed a morning show host pointing at the window behind him, and with a straight face suggesting, that for those viewers not being able to go outside, their windows could substitute the world outside. I didn’t know whether to laugh or to cry. The question of substitution becomes especially important when thinking about people who can’t experience things actually: How to replace the world for people confined to their homes? Even before the COVID-19 this was an important issue. For decades, there has been a growing market for technological innovations designed for the lonely, the disabled, and the sick. Now that a vast number of people have found that their world has been taken away, there’s suddenly a desperate need for some kind of a window back to it. If virtual is something that can replace the actual, the question is: what can be replaced, and what cannot?

However, virtuality is not simply synonymous with replacement; according to Wolfgang Welsch, its philosophical roots go back at least to Aristotle’s concept of dynamis, meaning literally potentiality – something later writers, starting from Thomas Aquinas, called virtual. However, dynamis, or Aquinas’ virtual, didn’t mean an alternative to the actual, but a prerequisite; a possibility, in the limits of which reality was able to actualize. In later centuries the nature of the concept changed with different writers, slowly disconnecting virtual from the actual. As the one-two step connection vanished, the virtual realms could in some cases even exist separately from the actual. The eventual actualization didn’t necessarily empty the realm of the virtual possibilities; they stayed alive, in some other realm. At some point, we ended up in the situation we’re in now, with the virtual and the actual existing in completely different, but in some ways, mutually supportive realms. (3–6)

The idea of having something beyond or before actuality, something to possibly support, to substitute or even to replace it, fits well to many phenomena in different eras, cultures, media, and genres: the idea might be generally human and global, a concept larger than the etymology of the term itself. In fact, all time periods and people have had virtual media of some kind, and experienced virtual travel in some form or another: reading books, going to the theatre, listening to stories, daydreaming, playing, and creating – all of them have a quality of substitution, of making plans awaiting realization, of dry running, of conceptualizing. Virtuality might just be a way of life for humans, to some extent.

The multiple nuances of the term enrich (or confuse) my research on the relationships of the cabinets of curiosity and similar collections had with the world: they can be seen, all at once, as representations of the wider world; as private worlds of the collectors; as cultural lenses to the world; or as worlds in themselves. Could the collections, just like the television and the internet nowadays, substitute the world at large, and be a replacement for travel? And whose travel was that – and whose world: the visitors’, the collector’s, or someone else’s?

The research on the virtual worlds in cabinets of curiosity can open up interesting connections to the modern-day conversations on virtuality. There is surprisingly little research that takes into account or even acknowledges the full history of the concept – usually the focus is on some niche contemporary meaning. Virtuality is not solely about technologies and illusionism, but about much larger and more fundamental themes: what is reality? What is experience? What is the effect of different kinds of media to experience and its authenticity? How does cognition work? How do we make sense, simulate, and create worlds?

This new and sudden era of virtuality might be a modern society’s attempt to cling onto an old version of the world; to save it in an ark – in ‘one closet shut’, as the Tradescants did with their collection. At the same time, something brand new is beginning to form. We might even realize that some of the old is not worth replacing after all. Perhaps the situation will force us to re-evaluate our priorities: is it more important to be constantly productive and active, or to take it slow, to keep in touch, to touch, to walk in the park, to be able to sit down outside and watch the spring arrive. What is the right ratio of the actual and the virtual for the recipe of human happiness? What even is real, and what does it mean to be real?

I’m sure that in the end, we will find the balance – we will all, yet again, adapt to the new world we are thrown into.

Saara Penttinen is a PhD Student at the University of Turku department of European and World History working on virtual worlds in seventeenth-century English cabinets of curiosity. She’s currently a visiting associate at the Department of English at Queen Mary University of London.

Featured Image: Engravings of the Tradescant Tomb from Samuel Pepys Drawings, Philosophical Transactions, 1773.

1 Pingback