By Shireen Hamza

“Without desire, …research would never take place: we would be unable, literally unable, to discover anything. But at the same time, we have to bring this under control.”

— Carlo Ginzburg, Twelve Snapshots from a Conversation with Carlo Ginzburg

“For too long, Black trans people have fought for our humanity, and for too long, cis people have been acting like they know what the fuck are talking about.“

— Ianne Fields Stewart, rally in Brooklyn, NY, on June 14th, 2020

In the year 952 AH/1545-1546 CE, writes the historian al-Muḥibbī, ‘Alī ibn al-Rifā’ī, a brown-skinned boy who had yet to grow a beard, was binding books in the Damascene district of al-Qaymariyya. A man named ‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ẓannī was passionately in love with ‘Alī. By the end of al-Muḥibbī’s tale, ‘Alī – now a woman called ‘Aliyyā – had given birth to several children with ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, and most of Damascus could attest to this. In al-Muḥibbī’s telling, ‘Alī’s gender shifts after both doctors and the jurist presiding over the court declare ‘Alī to be a woman, ‘Aliyya. However, the marriage contract that would have been drawn up for them would likely have shown a neater and more normative reality: that a man named ‘Abd al-Raḥmān wed a woman named ‘Aliyya. Reading about ‘Alī/’Aliyya makes me wonder: how many other stories of “non-binary” Muslims are hidden in plain sight in the documentary record of Islamic history? What keeps historians from seeing them? And who stands to benefit from an increasing awareness of the history of sex and sexuality in the Islamic world?

Many scholars of Islamic history acknowledge that gender and sexuality are historically contingent, and that the process of gendering people was enacted primarily through “social and legal discourses,” for example by Islamic law. However, scholarship on the premodern Islamic world often rests on the implicit assumption that there are, now and historically, only two “real” sexes – which many historians would contest. The process of premodern “sexing,” or medical sexual differentiation, was determined by physicians whose understanding of the body was rooted in a largely Galenic paradigm in which “ideas about conception easily explained nonbinary sex,” and the determination of sex “did not necessarily depend on genital morphology,” but also on a variety of other physical attributes.

Physicians’ understandings of sex did not automatically sort humans into men and women but included other sexes in between. These views in turn influenced jurists as well as authors of lexicons like Ibn Manẓūr and popular encyclopedias like al-Qazwīnī, for whom sex differentiation could lead a fetus to develop into one of five sexes: woman, masculine woman, khunthā, effeminate man or man. Thus, their discussions of surgery on a khunthā’s body are not described as corrections of sex or gender, but rather seek to relieve discomfort, enable intercourse for married people, and overall, to serve “an individual’s health and religious needs.” Paired with the understanding that one’s sex (and depending on whether this caused social disruption, perhaps also one’s gender) could change through the course of one’s life, medieval Islamic understandings of sex start to seem quite different from biological sex.

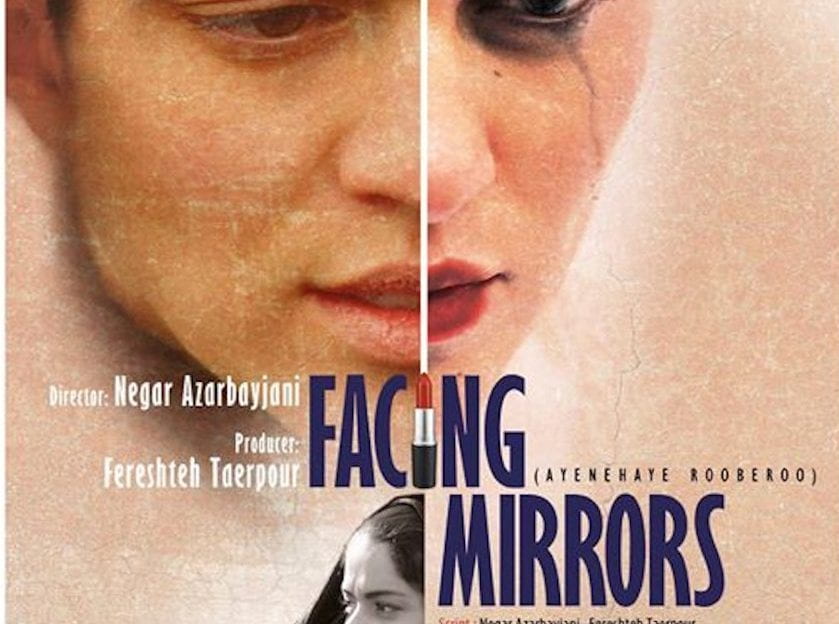

Stories like ‘Alī/’Aliyyā’s and ‘Abd al-Raḥmān’s have great importance for queer and trans Muslims, to whom a range of conservative institutions suggest that Islam and LGBTQI+ identities are incompatible. Iran and Pakistan have received significant attention for their government programs providing specific kinds of trans affirming healthcare (in contexts in which homosexuality is illegal). Such government programs are grounded in a legal synthesis of biomedical and classical Islamic legal understandings of sex. Although official government policy has not led to widespread societal affirmation of trans, hijra or khwaja sira people in these countries, these institutional changes are a crucial part of a broader transformation. Iran’s legal stance on trans people has enabled contemporary Iranian filmmakers like Negar Azarbayjani, director of Facing Mirrors, to tell stories of contemporary trans people cinematically. Historians have the power to access and amplify narratives from the past that may inform both institutional and societal change today.

Historians of the premodern Islamic world study different configurations of law, medicine and state power. The work of historians shows that when the state has intervened on issues of ambiguous sex, the outcomes for those whose sex is called into question are not always positive, as with the wife of Muḥammad ibn Sallāma in 1506 CE. Amīr Ṭarābāy called on women, presumably women with medical training, to determine the sex of Muḥammad ibn Sallāma’s wife. After determining that she was not a woman or a khunthā but a man, the Amīr brutally punished the couple, who died as a result. Although difficult to read for queer and trans people who are subject to myriad forms of violence, this story is nonetheless one which shows that people troubled binaries of sex and gender in the Islamic past, thus suggesting that the presence of gender nonconforming and trans Muslims today is no aberrance.

But these stories are also important for physicians to hear. The history of medicine includes episodes of harm and coercion as well as of care, healing and ingenuity. There is growing historical research on how binary sex and heterosexuality were conceived of and enforced by nineteenth century physicians, scientific sexologists, psychoanalysts, science-writers for the popular press, and many actors of colonial and/or national governance in the Middle East, South Asia, Africa, Latin America, and here, in the settler colony known as the US. There is a history to the “straight” understanding of sex and sexuality – the social and medical views that there are only two true, fixed biological sexes in humans and that heterosexuality is natural. Just recently, as Sean Saifa M. Wall, an intersex activist, says:

Variation in sexual anatomy… should show us how beautifully diverse nature is. It should remind us that anatomical sex is not fixed, but fluid. …But sometimes it feels like debating ethics with butchers. Too many in the medical profession see surgery as their duty.

It is striking how wondrous some writers in the medieval Islamic world considered this fluidity of sexual anatomy to be, while this fluidity has been considered an aberration or monstrosity in other times and places, including our own. Physicians, public health officials and historians are increasingly acknowledging scholarship on the “coloniality of gender” as relevant to their professions – a scholarship which shows how race, gender, sexuality and other emerging categories were co-constructed for marginalized people in both metropole and colony. Physicians in precolonial contexts operated within medical systems that did not rest on binary sex, but within legal and social systems which did tend towards binary gender. Historical accounts of healthcare before colonialism may also provide healthcare workers today with food for thought. While ethicists are calling healthcare providers toward practicing “justice, beneficence and nonmaleficence” by following specific actions in their treatment of trans and gender nonconforming patients in systems not built to accommodate them, the distant past may help us imagine futures beyond the confines of the present.

***

‘Alī was a boy until he was a khunthā; he was a khunthā until she was a girl. In this description, I follow the gender pronouns ascribed to ‘Alī by al-Muḥibbī. No explicit reason is given as to why ‘Alī and ‘Abd al-Raḥmān were called before the judge, Kamāl al-Dīn al-’Adawī, but al-Muḥibbī suggests that it had to do with ‘Abd al-Raḥmān being in love with ‘Alī. The judge said, upon first consideration, that ‘Alī seemed to be a khunthā, and that he “tended towards being female.” He called in physicians to examine him. These physicians discovered a vulva, hidden beneath a (skin) covering with “three small nipples,” which they cut away. The judge ruled on ‘Alī being a woman, and they named him ‘Aliyyā. al-Muḥibbī then starts referring to ‘Aliyyā with the feminine pronouns, to say she was married to her lover, ‘Abd al-Raḥmān.

حكم الحالكم الشافعي بأنوثته و سموه عليا و زوجوها بعاشقها عبد الرحمن

The Shafi’i Judge ruled on ‘Alī’s womanness, and they named him ‘Aliyyā and married her to her lover ‘Abd al-Raḥmān.

al-Muḥibbī offers no explanation as to who this “they” is, but the sentence implies that it was people other than the judge who did so.

In this story, the authority of physicians and the law, combined, officially changed ‘Alī’s gender with almost no surgical intervention. As al-Muḥibbī reports, most of the people of Damascus knew about these events and could attest to their veracity – implying, perhaps, that rather than any public outcry, the story was considered strange, wondrous, marvelous. al-Muḥibbī’s account, and many other stories involving physicians, leave many important questions about medical ethics unanswered. Was the love ‘Abd al-Raḥmān had for ‘Alī requited? Did ‘Alī consent to the examination and intervention by doctors? Did ‘Alī want to live as ‘Aliyyā, and as ‘Abd al-Raḥmān’s wife? And yet, this story – by no means an ideal for doctors and courts today – has the power to unsettle people’s presumptions about sex, gender and sexuality.

Several kinds of texts and documents form a fragmentary and checkered archive for understanding the lives of khunthā, people neither men nor women of a “medial sex” in the premodern Islamic world. Both medical texts and juridical texts speak to what the doctor and jurist should do when encountering someone whose sex is ambiguous. As Saqer Almarri writes in his translation of the passages about khunthā in one such legal text, “evidence of the historicity or the specificity of the lives of people” is rare, but legal manuals still tell us something about the social and cultural contexts that shaped them. Surviving legal documents, however, show us glimpses of law in practice, as records of events like marriage, divorce, business transaction and partnerships, disputes, the purchase or sale of enslaved people, and inheritance. While some kind of narrative emerges from these documents, they are not always as detailed as the one about ‘Alī/’Aliyyā related by al-Muḥibbī above. In practice, as Sara Scalenghe argues, jurists like al-Ramli in the seventeenth-century often “chose to brush aside the evidence of contradictory signs of maleness and femaleness” in order to enable someone to continue living within a gender role, opting for “the least problematic verdict.” Historical chronicles took biography or “life-writing” of exemplary figures, as well as ordinary and even disreputable people, as the unit organizing history. The stories in these chronicles do not often describe the “adjudication by urination” (ḥukm al-mabāl) test that is ubiquitous in legal manuals as a way to determine whether a khunthā is a man or a woman, casting doubt as to how prominently this was used in practice. In short, none of these texts allow us unmediated access to the lives of people categorized as khunthā in the premodern Islamic world. The best work on the khunthā and other elusive archival figures, like hermaphrodites in early modern Europe, has been done by reading across multiple genres.

The texts and documents themselves may give us reasons as to why some genres are forthcoming, and others entirely silent, about the khunthā. To the best of my knowledge, the mention of someone as a khunthā in marriage or divorce contracts is rare or nonexistent because, as both the historical and juridical manuals show, jurists tried to resolve cases by declaring a khunthā to be either a man or a woman. This enabled a khunthā to live as either a man or a woman, sometimes with a lover who had previously been forbidden, as in the case of ‘Alī/‘Aliyyā’s marriage to ‘Abd al-Raḥmān. Databases make digitized documents in Arabic and Persian, including marriage contracts, increasingly accessible, but this additional awareness of historical realities is also necessary when approaching these kinds of documents. Otherwise, the silencing, first enacted in the creation of the archive, is repeated by the modern historian. As scholar Indira Falk-Gesink says:

Twentieth-century academic prejudices colonize and efface the sexualities of the past, overwriting authors’ words with “corrective” translations, in the process constructing a palimpsestic narrative laden with heteronormative cisgender assumptions that invalidate the efforts of contemporary Muslim activists to reconstruct authentic bases for pluralism.

Let us rid ourselves of these prejudices in our engagements with people, past and present.

***

Recently, the Trump administration sought to establish a definition of fixed, binary sex based on genetic science, thereby making irrelevant “what the medical community understands about their patients – what people understand about themselves.” The administration tried to eliminate transgender civil rights protections to nondiscrimination in healthcare in the middle of a pandemic, and on the anniversary of the massacre at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando. Transgender people have long faced refusal of care and harrassment in medical settings, and if not overruled by the Supreme Court, the suggested changes to the definition of sex would have made discrimination against trans people legal.

I am not arguing that there is a direct, linear correlation between reading stories of sex and gender diversity in the Islamic world and affirming and accepting behavior towards people today. There is no shortage of literature, scholarly and otherwise, about the ways certain pious Sufis flouted norms of gender and sexuality in their search for earthly and divine love, but this is a vision of the Islamic past that is increasingly decried and censored. And as previous generations of scholar-activists have done, today’s scholars of Islamic Studies need to pair research on past marginalized lives with advocacy for those in the present.

And for those who are interested in providing medical care that fully addresses the needs of queer and trans Muslims to be affirmed in body, mind, spirit, and history, a collaboration between historians, medical workers, faith workers, archivists and community organizations may be necessary. Too often, LGBTQI+ Muslims are presumed to have automatically left faith behind. Those working in healthcare may find that – despite the gruesome reputation that premodern and especially medieval medicine has in popular culture – there are yet reasons to reflect on these past encounters. There may be resources available therein to stimulate conversations about how to better serve the needs of queer and trans Muslims.

Most Islamic bioethics is rooted in the literature produced by jurists and ‘ulamā’ broadly, rather than considering the words and actions of ordinary Muslims, insofar as we can discern them, to be a resource. But to the many Muslims living on the margins of the umma, there may be other voices that are important for historians to attend to and amplify, and for bioethicists and physicians to consider. For example, stories like ‘Alī/‘Aliyyā’s are meaningful to many queer and trans Muslims today — although the use of terms like LGBTQI+ to describe people in the past has been interrogated extensively by historians, who prefer us to learn the terms used by those past people, when we can. But the affinity of many queer and trans Muslims with different kinds of “deviant” and marginalized people in the Islamic past runs deeper than finding lexical similarities with the identities some people use today. This June, a month of pride, is also one of the remembrance of ancestors, and mourning for those lost – whether to murder, to suicide or to the indifference of governments during a pandemic.

Historians bring our own desires to the texts we read. No longer do those in the ivory tower claim a view from nowhere, an objectivity – this claim, too, has been historicized. The desires of LGBTQI+ Muslims today for stories that may have a bearing on the community’s intense marginalization should be heard as a call to action for those of us with the time, privilege and skillset to be able to heed it. This desire is one to center and respect in our research, whether one believes one works on sex and gender or not. It is a desire that has been, and will be, generative – not only for research, but for the lives of everyday people.

Shireen Hamza is a doctoral candidate in the History of Science at Harvard University, working on the history of medicine and sexuality in the premodern Islamic world. She is also a managing editor of the Ottoman History Podcast and editor-in-chief of Ventricles, a podcast on science, religion and culture.

Featured Image: Poster of Facing Mirrors. Directed by Negar Azarbayjani. Facing Mirrors is defined by The Film Collaborative as “the first narrative film from Iran to feature a transgender main character.”