By Tamara Maatouk

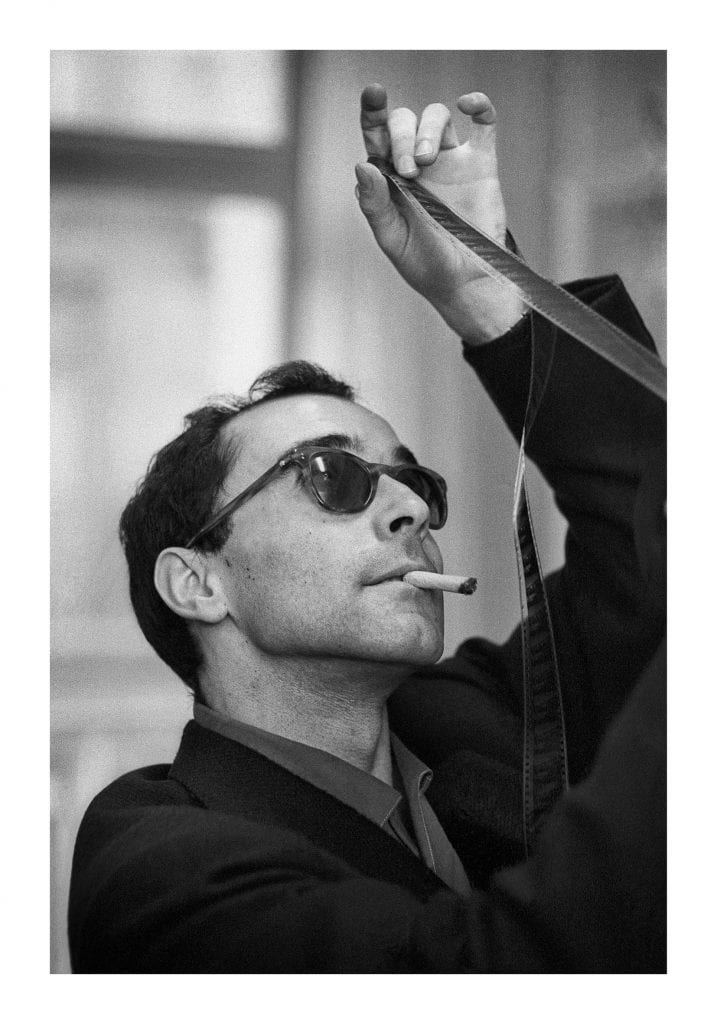

An author, Michel Foucault wrote, is a “founder of discursivity” whose work establishes new modes of discourse, from which further texts can be formed. Jean-Luc Godard, I argue, is such an author, a film author to be exact; he has produced a new and distinct cinematic language, with unique aesthetics and recurring thematic concepts, that other filmmakers used, built upon, and transformed. A renowned French-Swiss cineaste and a pioneer of the French New Wave, Godard blatantly rejects established cinematic conventions and norms. His films are known for their nonlinear narrative, self-reflexivity (showing the filmmaking process as well as referencing other films and texts), existentialist themes, and Marxist outlook—all of which form a distinctive ‘Godardian’ style and have culminated in his masterpiece Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998). In Histoire(s), as well as in films such as Ici et ailleurs (1976) and Le Livre d’image (2018), Godard speaks to his immediate present, interrupting cinematic time and juxtaposing different temporalities, as he chronicles the world around him. In so doing, I argue, he transcends the technical boundaries of a filmmaker and instead begins to resemble the history-laden figure of the flâneur.

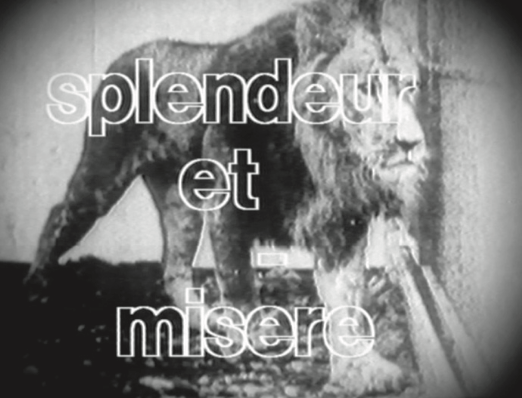

© 1988/1998 Gaumont

In the late 1970s, Godard started working on Histoire(s), which he initially conceived of as a series of lectures on cinema and published in 1980 as Introduction to a True History of Cinema and Television, only to turn it into an eight-part audio-visual essay later on. He produced the first episode (Toutes les histoires) in 1988, which was screened out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival in that same year, and the last episode (Les Signes parmi nous) ten years later in 1998, which premiered as part of Un Certain Regard at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival. Heralded as one of his most complicated projects, Histoire(s) recounts the history of cinema from its birth in the late 19th century to the late 20th century. To this end, Godard superimposes film excerpts with paintings, photographs, illustrations, texts, musical tracks, and audio commentary, weaving together a critical and reflective assessment of cinema, its relationship with other arts and modes of expression, its (mis)representations, manifold transformations, and failure to adequately address the major problems of its time.

Yet, Histoire(s) is equally about Godard himself and his place within the history of cinema, as a form of self-portrait—and, as Michael Witt has argued, about “the history of the twentieth century; [about] the interpenetration of cinema and that century; and [about] the impact of films on subjectivity.” As such it is also, as Witt has continued, “a critique of the longstanding neglect by historians of the value of films as historical documents, and a reflection on the narrow scope and limited ambition of the type of history often produced by professional film historians.” Godard’s nonlinear approach to the history of cinema through the lens of cinema, exemplified by Histoire(s), represents an alternative to traditional historiography, namely the singular narratives that focus primarily on the linear progression of formal, literary, and technical elements of cinema. Throughout the making of Histoire(s), Godard transforms from a filmmaker into a flâneur, and from a flâneur back into a filmmaker, becoming a historian of his present along the way. Because of his involvement in the film industry as a passionate observer-participant who is living in the present-ness of his time, Godard is able to visualize the history of cinema from archival material, memory, and lived experience.

The flâneur as a modern urban character was first introduced by Charles Baudelaire in his 1863 text “The Painter of Modern Life.” Fascinated and influenced by Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Man of the Crowd,” Baudelaire described the flâneur as a male “passionate spectator” whose profession is “to become one flesh with the crowd,” and who aspires “to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world.” The flâneur, Baudelaire continued, “rapturously breathing in the odours and essences of life,” commits all of his observations to memory, as he “remembers, and fervently desires to remember, everything” (7-9).

Drawing on Baudelaire’s description of the flâneur while borrowing from other hommes de lettres, Walter Benjamin turned this figure into an archetypal symbol of modernity in his unfinished Arcades Project. Adding many other features to the flâneur as both a literary subject and historical figure, Benjamin arrived at the conclusion that “preformed in [this figure] is that of the detective” (442), whose “social base of [this] flânerie is journalism” (446), who is empathetic and, as Gustave Flaubert contended, “see[s himself] at different moments of history, very clearly” (449); a character who is “industrious,” “productive,” “makes ‘studies’” (453), and who “recognize[s] the social strata of [his] society… as easily as a geologist recognizes geological strata” (434). From Pierre Larousse, Benjamin further borrowed the following description of the flâneur:

His eyes open, his ear ready, searching for something entirely different from what the crowd gathers to see. A word dropped by chance will reveal to him one of those character traits that cannot be invented and that must be drawn directly from life: those physiognomies so naively attentive will furnish the painter with the expression he was dreaming of; a noise, insignificant to every other ear, will strike that of the musician and give him the cue for a harmonic combination; even the thinker, the philosopher lost in his reverie, this external agitation is profitable; it stirs up his ideas as the storm stirs the waves of the sea… (453)

For Benjamin, the flâneur was no longer a passive observer, but an active participant who knows his society very well but is detached enough to study it. Further, if he documents his present observations the way Benjamin did, he may play a role in collective memory formation or knowledge production (and preservation). What makes this possible is the flâneur’s different perception and experience of time and space from that of the crowds on the streets, manifested by his constant need to have “elbow room,” and by his trendy hobby of walking a lazy turtle through the arcades, which he believes “can set the pace for [him]” (54). The flâneur, therefore, has time on his hands and does not feel the urge to keep up with the accelerated pace of change or life in the modern city. Instead, he slows time down, decodes and documents everyday life, and, as Alexis Dumesnil notes, compiles “a record of each individual’s thoughts and objectives at that particular moment […]” (432).

The first to comment on Benjamin’s conception of the flâneur as well as his own similarities to this figure was, most probably, Hannah Arendt, who drew a connection between the flâneur, time, progress, and the meaning of history. “It is to him,” she wrote, “aimlessly strolling the crowds in the big cities in studied contrast to their hurried, purposeful activity, that things reveal themselves in their secret meaning.” But Arendt went even further by comparing the flâneur with Benjamin’s “angel of history,” concluding that as “the flâneur… turns his back to the crowd even as he is propelled and swept by it, so the ‘angel of history,’ who looks at nothing but the expanse of ruins of the past, is blown backward into the future by the storm of progress.“The flâneur, then, lives in the present, fascinated by it; unlike his contemporaries, he experiences the present not as transient moment or a vanishing point, but as his only actuality, with the future figuring only as a most distant concern.

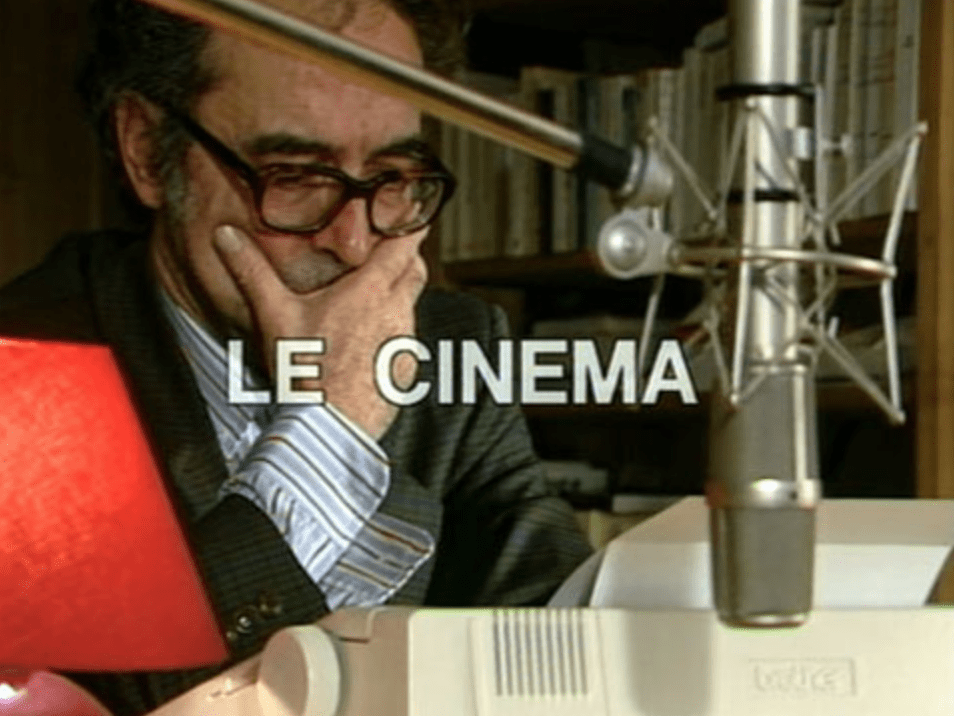

Like a flâneur, Godard acts both as a detective and as a journalist, embarking on an investigative journey in Histoire(s) to explore the origins of the cinematic forms that influenced him. He sees himself at different moments of history, visually documenting observations he made over the course of four decades as a fascinated cinephile and an engaged filmmaker—as both a passionate spectator and an active producer. Godard creates a collage-like visual essay out of clips from various films and other visual arts, moving from one image to the next, from a video to a painting, a text to an audio clip, without giving any explanation, leaving the task of understanding the association of ideas to the spectators, who will have to depend on their visual and aural senses to identify and interpret what they are witnessing. At the same time, Godard inserts a piece of himself into Histoire(s), acting as a storyteller whose voice-over narration complements the visuals he is projecting, recounting, in his words, “what was impersonal in this first-person novel, and personal to everybody” (12-13).

At once at the center of Histoire(s) and hidden beneath its many layers, Godard thus appears productive yet pensive. Being an “insider,” a part of the very history that is the subject of his study, makes it possible for him to chronicle the predominant thoughts, styles, and ideologies at any particular moment. His ability, however, to take a step back and live in the present also allows him to see the cinematic society from afar. Such aptitude helps him to set his own pace, which, in turn, grants him some room to capture more transient images, retrieving the fragmented stories which have evaded his psyche. Throughout Histoire(s), Godard aims to recover and restore the memory of cinema as it is: disjointed, chaotic, multilayered, and, many times, incoherent. Godard then strolls down cinema’s memory lane, inviting his audience to wander along with him, sometimes identifying the material he examines, but other times letting an image or a sequence of images speak for itself. He is fascinated by what he sees and discovers, and not in a rush to move forward—for he fears the death of cinema is imminent. Instead, he wants to stay in the moment and turn toward the past, examining one fragment after the other in hopes of finding answers to the questions of his present, the most recurring of which revolves around the failure of cinema to create social and political change and to “fight the bourgeois concept of representation.”

Tamara Maatouk is a doctoral student at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, where she studies Middle Eastern history. She is the author of Understanding the Public Sector in Egyptian Cinema: A State Venture.

Featured Image: Histoire(s) du cinéma, Director: Jean-Luc Godard. © 1988/1998 Gaumont