Cynthia

It’s been a long hot summer here in New York, and we are only halfway through the season.

Paul Fusco died on July 15th. Two days later, on July 17th, John Lewis died.

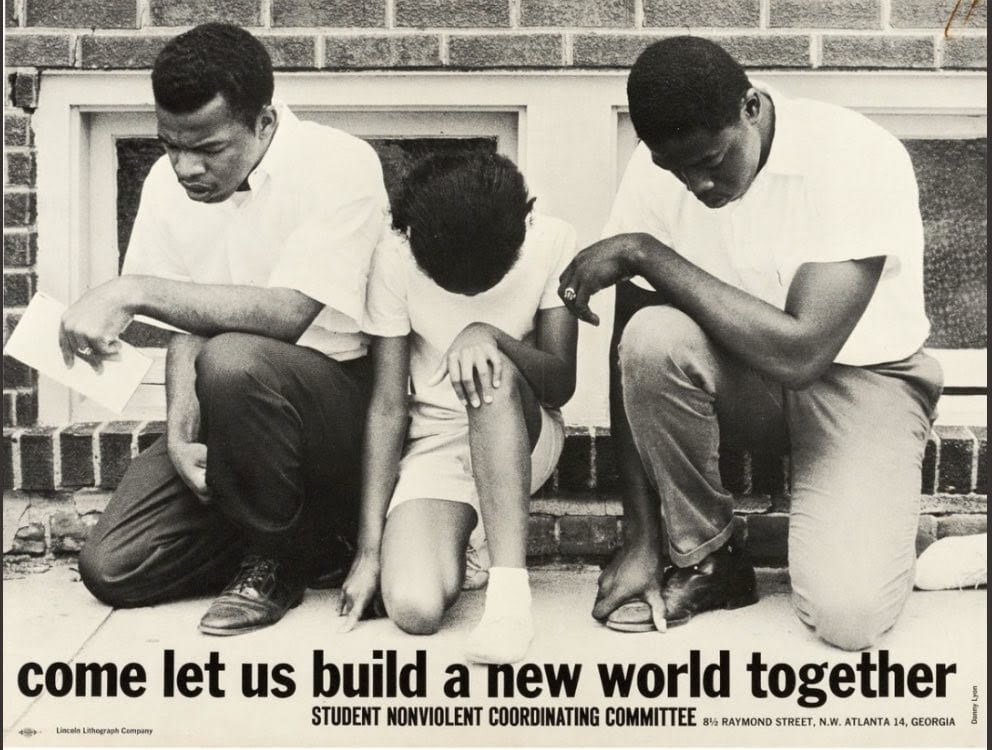

John Lewis needs no introduction. By now, you’ve probably seen this 1963 Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee poster, featuring a young John Lewis:

In the midst of another long hot summer, Danny Lyon hitchhiked to a small town in Illinois called Cairo. It was 1962. As Lyon recounted in an essay for the New York Review of Books, “One of my classmates, Linda Pearlstein, had been arrested in civil rights demonstrations in Cairo, Illinois. With contacts from Linda, I put my 35 mm Nikon F reflex into an old army bag, asked my sister-in-law to drive me to Route 66 at the city’s edge, stuck out my thumb, and hitchhiked south. I thought I was just going on an adventure.”

Lyon made this photograph on his second day in Cairo. He followed “a small group” to “a segregated swimming pool that sported a “Private Pool, Members Only” sign.” The group knelt to pray, and Lyon saw before him “a sublimely beautiful moment: the grace of the three, the two men kneeling at each side, the child in the middle.”

Lyon met John Lewis in Cairo. The two would go on to work together in the SNCC, and they also became lifelong friends. You can see the two in conversation in this interview from 2016, on the occasion of Lyon’s retrospective, “Message to the Future.” Lyon recalls how he found his calling as a photographer that same hot summer: “[When I arrived in Albany, Georgia,] over my shoulder was a Nikon F reflex. “You got a camera,” James Forman—then SNCC’s executive secretary—said to me when we met at the Freedom House. “Go inside the courthouse. Down at the back they have a big water cooler for whites and next to it a little bowl for Negroes. Go in there and take a picture of that.”

Go in there and take a picture of that.

*

Paul Fusco had a long and productive career as a photographer. He began as a staff photographer for Look magazine in the heyday of magazine photography. After LOOK shut down, fusco joined magnum photos. Fusco is perhaps best known for his photographs of Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral train. Kennedy was shot on June 4, 1968. After the funeral on June 8th — held at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, where for 2 days crowds lined up for blocks to pay their last respects — a slow train carried RFK’s casket from New York to Washington. D.C. Fusco was also on that train. “All I was thinking about was how to get access when we got to Arlington,” he said. “Then, when the train emerged from beneath the Hudson, and I saw hundreds of people on the platform watching the train come slowly through — it went very slowly. I just opened the window and began to shoot.”

*

I invite you to take some time to sit with these photographs.

And then, turn your attention to Danny Lyon’s reminiscences of John Lewis, interleaved between other topics–some heavy, others mundane.

I invite you to sit with these images, sit with the people in them, some of them ghosts now, and look upon them with a regard both raw and tender. Walk through their blind departure. Feel the rush of the past, the still point of the present.

*

Danny Lyon, again: ‘That day in Washington when John showed me the star where Dr. King had stood, I listened to Al Sharpton, the keynote speaker at the 2013 march, as his voice boomed out through the public address system.

“And when they ask us for our voter ID, take out a photo of Medgar Evers. Take out a photo of Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner. Take out a photo of Viola Liuzzo.

“They gave their lives so we could vote. Look at this photo. It gives you the ID of who we are.”’

*

Look upon them with a regard both raw and tender.

Take up the labor they left undone.

Maryam Patton

Early Modern Aristotle: On the Making and Unmaking of Authority

What did Aristotle really believe? For early modern humanists and scholastics, the answer depended, not surprisingly, on whom you asked and to what end they were either defending or decrying his views, and why. Professor Eva Del Soldato’s brand new book Early Modern Aristotle: On the Making and Unmaking of Authority revisits the debate over whether the ‘re-discovery’ of Plato (and other ancients) was the true hallmark of a Renaissance renovatio that triumphed over the stodgy Aristotle of the universities, or whether, in actuality, Aristotle as a thinker was re-imagined and re-figured to serve new ends. She argues that Aristotle, just like any ancient thinker, was a stand-in for a figure of authority and thus was tailored to suit certain, sometimes contradictory, agendas, further substantiating Charles Schmitt’s efforts to illustrate the multitude of early-modern Aristotelianisms. Del Soldato convincingly traces the use and abuse of Aristotle through thematic chapters acting like case studies, beginning with the late Byzantine genre of comparatio and a thorough study of the sheer variety of the conclusions found in early modern Latin comparatio. I especially enjoyed the final two chapters on apocryphal proverbs attributed to Aristotle, and the genre of texts in the vein of “if Aristotle were alive…,” what would he really think?

Stay tuned for my forthcoming interview with Professor Del Soldato and the role of authority in Early Modern Europe, on JHIBlog.

Simon Brown

Karl Marx projected from the 1860s that the capitalism shaping the London around him would concentrate more and more proletarian workers in conditions of immiseration, while also leaving them more and more “disciplined, united, organized.” The factories that now defined the capitalist landscape pulled their denizens out of their domestic workshops, placing their occupants side-by-side with strangers rather than their families (who had also been their coworkers, or subordinates). There was no reason to think that the factories’ magnetic power would not attract more and more people inside, while those workers — and the class condition that unified them — became less and less anonymous to one another. From our standpoint looking back, the turn to remote work out of urgent necessity but likely to continue as a general trend reverses the story of capitalism’s tendency to physically bring together more working people. But computer programmers, grad students and clerical workers have not evacuated factories but rather offices, and the advent of the large office space and the economy that called it into being posed its own challenge to Marxist thinkers that sought to hasten the end of capitalism and the conservative commentators that celebrated its individualistic spirit. That history of how critics thought about the office space and its implications for work and social relations is brilliantly interwoven through Nikil Saval’s Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace (Vintage, 2014).

Saval traces literary representations and critical reflections on the nature of the modern office space and the “white collar” work that it typifies, from “Bartleby, the Scrivener” to Office Space. That intellectual history runs through absorbing accounts of architectural innovations and modern interior designs. Behind nearly every new office layout or skyscraper design was an idealistic aspiration to make work more human, which was subsequently undercut by the financial imperative to optimize limited space and maximize return on profit. The notorious cubicle farm originated in the optimistic “Action Office,” which would allow the “knowledge workers” of midcentury the opportunity to encounter and meet with their colleagues in ample space. We’ve inherited a powerful intellectual tradition from the post-war period that looked askance on offices as incubators of conformity and alienation. But reading this history from our current WFH moment left me longing for a common office space with my colleagues. University campuses aren’t quite the same as offices, though early twentieth-century office spaces like Bell Labs were intentionally designed to emulate the “chance encounters” in university departments, as Saval shows. Those chance encounters aren’t just opportunities to exchange teaching tips (though that’s helpful too). They’re also the occasion to talk about work, what we need, and how we can work together to get it. Marx focused on the factory, but he still saw real political potential in that space of coworking that could never be entirely closed. The office has always left space for those conversations as well, usually to the consternation of the people in the corner offices.

Find more reading suggestions in our July Reading Recommendation Part 1.

Featured Image: Raphael, Portrait of Pope Leo X with two Cardinals (detail). Uffizi Gallery, Florence.