by Daniel Wortel-London

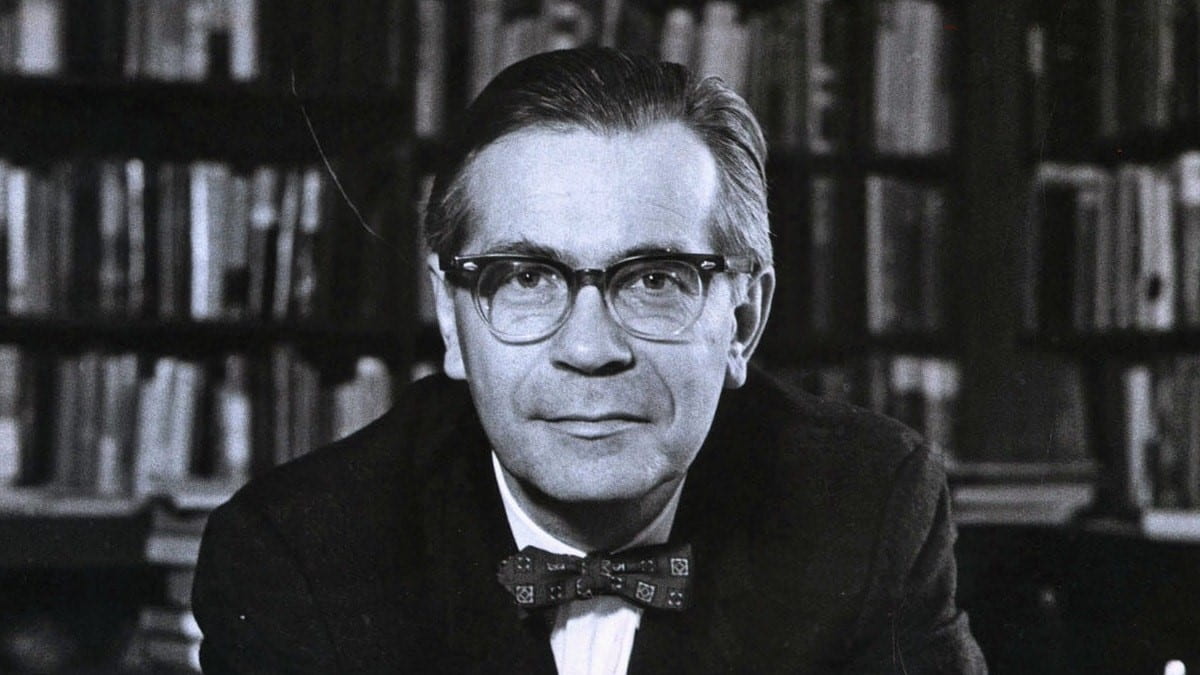

Richard Hofstadter (1916–1970) was a prominent historian of American political culture. He taught for many years at Columbia University, was twice awarded the Pulitzer Prize, and is remembered for works such as Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963) and the essay collection The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1964). Beginning his academic career as a man of the left, by the 1950s Hofstadter had become associated with the postwar “consensus” school of historiography—a label he was never entirely comfortable with. In his many books and essays, Hofstadter paired his appreciation for historical irony and complexity with iconoclastic criticisms of both leftist shibboleths and liberal complacencies. It was, however, above all to the American conservative tradition—which he lived to see take new and virulent forms in the later 1960s, before his death of leukemia at fifty-four—that he devoted his attention and analysis.

Then as now, Hofstadter’s focus on the cultural and psychological dimensions of right-wing politics have attracted both praise and controversy—particularly as, since 2016, commentators have once again debated the political valence of populism, the purported psychological roots of partisanship, and the nature of both consensus and polarization in American politics. This has prompted the Library of America to publish a three-volume new edition of Hofstadter’s major works, reportage, and unpublished essays on American politics and culture, edited by Princeton University historian Sean Wilentz. The first volume appeared in April 2020 as Richard Hofstadter: Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Uncollected Essays 1956-1965. Daniel Wortel-London interviewed Wilentz about Hofstadter and this new edition.

Daniel Wortel-London: Hofstadter understood himself as a political historian, but one of a particular type. While initially attracted to “orthodox political history” (“History and the Social Sciences,” 1956), he admitted that his work largely forwent its classical questions: how public institutions are formed, how political and economic power is structured and distributed, and the “who gets what, when, and how” considerations of political life. Instead, his main objective was to understand the “ideas, moods, and atmosphere” that conditioned “who perceives what public issues, in what way, and why” (Introduction, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, and Other Essays, 1964). Nonetheless, Hofstadter’s treatment of ideas tended to differ from the “unit-idea” approach of Arthur Lovejoy and contextual approaches later developed by Quintin Skinner and J. G. A. Pocock. How would you characterize Hofstadter’s approach to the history of ideas?

Sean Wilentz: Richard Hofstadter was a political historian deeply attuned to ideas and, to some extent, an intellectual historian deeply attuned to politics. His approach arose in part from his undergraduate training in philosophy at the University of Buffalo. It also owed a great deal to his interest in literature and literary criticism. His connection to his close friend Alfred Kazin as well as his admiration for critics like Edmund Wilson were very important to his own intellectual style. Above all, his work originated in his lifelong confrontation with the Progressive historians, especially Charles A. Beard, who became something of a fixation. Whereas Beard emphasized conflict and saw material forces, or certain material forces, as determining politics, Hofstadter discerned continuities and unities, and he saw ideas, and in time ideologies and social psychology, as crucial as well. None of it directly originated in any particular school of intellectual or cultural history: it came chiefly out of his growing up in the 1930s amid the Great Depression, his early interest in Marxism, then his disillusionment with and reaction to what he beheld as the dogmatic idiocy as well as the bad faith and treachery of the Stalinist Left. I included in the Library of America volume a section from a hitherto unpublished memoir where Hofstadter laid all of this out, describing what he called his mode of “analytical” history. Later on, he became very interested in the writings of Karl Mannheim as well as the Frankfurt School—especially Theodor Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality (1950)—which was part of the intellectual ferment in and around Columbia that was connected to the world of the New York Intellectuals. You can’t fully understand Hofstadter’s use of categories like “status anxiety” or “pseudo-conservatism” without appreciating his immersion in the foundations of what became known as Critical Theory.

One point on politics: although not so much drawn to writing about the mechanics of institutional politics, that side of things—elections, campaigns, and so forth—interested him as well, as some of the essays in this new volume show, notably one on the election of Herbert Hoover in 1928. Hofstadter knew his “orthodox” political history inside out. His abiding interest in these things shows up most clearly in what I sometimes think will be his most lasting, if not necessarily his most striking work, the undervalued The Idea of a Party System (1969). A study of how a party system based on comity as well as conflict came into existence, it brilliantly illuminates the transition from the founding era, which deemed parties evil engines of ambition, to the age of Jackson, which deemed them as absolute necessities in a popular democracy.

DWL: Hofstadter includes a surprising variety of types within the ranks of “intellectuals.” That category encompasses both “experts” (for example, postwar social scientists with their claims of nonpartisanship, pragmatism, and disinterested knowledge) and “ideologues” (Communist Party members with their outright partisanship and millenarian vision, various strands of Bohemia such as the Beatniks of the 1950s and the Greenwich Village radicals of the 1910s). How does Hofstadter define “intellectualism”—or, conversely, “anti-intellectualism”—in American life?

SW: There is a strong passage in the book, maybe my favorite, where Hofstadter distinguishes most clearly between what he calls intellectual practice and expertise: “It accepts conflict as a central and enduring reality and understands human society as a form of equipoise based upon the continuing process of compromise. It shuns ultimate showdowns and looks upon the ideal of total partisan victory as unattainable, as merely another variety of threat to the kind of balance with which it is familiar. It is sensitive to nuances and sees things in degrees. It is essentially relativist and skeptical, but at the same time circumspect and humane.”

Notice that the definition is imbued with liberal values—compromise, shunning absolutes, sensitive to nuances—that cut across conventional politics labels of liberal and conservative but renounce perfectionism and, for want of a better term, political eschatology.

That definition is obviously of urgent importance today, amid the raucous anti-intellectualism coming chiefly from the right but also from the activist and academic left. Some of that spirit—I wouldn’t presume to speak for all of the signers—informs the recent open letter in Harper’s, which I was proud to sign. Several critics have denounced that statement as a declaration by privileged, successful people against the voice of the excluded, or the righteous, outraged masses. Thus the firing and blacklisting of people whose words violate a rigid, self-regarding orthodoxy gets justified, perversely, as a blow against elitism. Thus the hunting down and punishment of heresy becomes equated with the vindication of truth. I can think of no better current example of the clash between intellectualism and anti-intellectualism as Hofstadter described it more than fifty years ago. Remember, long before the McCarthyism of the 1950s, Hofstadter had to contend with the Stalinism of the 1930s; his idea of intellectualism saw common elements in both. So we are faced with versions of both today. Between Trumpism and the heresy hunters among the social justice warriors, it’s hard to miss how significant anti-intellectualism remains. And to be clear: by “anti-intellectual” I don’t mean opposition to writers acclaimed as intellectuals, although resentment of accomplishment certainly enters in. I mean something closer to opposition to open debate, with a presumption that one’s adversaries and their ideas are not merely mistaken but morally reprehensible.

DWL: Hofstadter argues that anti-intellectualism is partly the product of “benevolent impulses” towards equality and egalitarianism. Expertise, for example, can be equated with hierarchy, pursuit of nuance can appear synonymous with political inaction, and personal experience can be seen as more “honest” than abstract facts. As a result, he argues that anti-intellectualism can only be contained and checked “by constant and delicate acts of intellectual surgery which spare these impulses themselves” (Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, p. 23). How can this surgery best take place today, particularly regarding those whose “benevolent impulses” might lead them to join progressive or radical social movements that seek to challenge several additional (and in my view, far more powerful) factors Hofstadter identified as threats to intellectual life: the influence of powerful business groups wary of criticism and an unimaginative and complacent political class?

SW: In his early writing, Hofstadter seemed more sympathetic to agitators than political leaders. The one figure in The American Political Tradition who broke with the dominant democracy of cupidity is Wendell Phillips, the “golden trumpet” of abolitionism and later a supporter of the labor movement. At one level, that portrayal allowed for a consistent radicalism in American politics but also sketched the limits of its power. Long before a younger generation of scholars began dog-earing copies of Antonio Gramsci, Hofstadter laid out what he saw as a kind of liberal capitalist hegemony in American politics. And in that respect, his work has sometimes ended up encouraging a cynical view of American mainstream politics, in which social movements do all the good, only to be coopted and ultimately defeated by more progressive liberal elements of the ruling class. Hofstadter never subscribed to that view: he still found Jefferson, Lincoln, and the others honorable and valuable. But the distinction between movement politics and party politics was certainly implied in his early work.

The McCarthyite experience helped shift that. Whereas he had previously criticized Popular Front myths by debunking their sentimentalized depictions of Jefferson, or Jackson, or Lincoln as champions of the people, he later came to criticize the sentimentalized view of popular movements themselves, above all the Populists. Along the way, he began having more sympathy for mainstream reformers. Compare, for example, how The American Political Tradition (1948) handles FDR with how The Age of Reform (1955) does. Hofstadter was still working out his critique of social movement politics in Anti-Intellectualism (1963) and The Paranoid Style (1964).

I think that toward the end of his life, he was trying to find a way to handle the kind of surgery you talk about. You see hints of that in The Idea of a Party System (1969), where professional party politics becomes more than an anti-intellectual engine of greed. You see other hints in America at 1750 (1973), a stark portrayal of the suffering among slaves and indentured servants that lay behind what he saw as an essentially middle-class society. I imagine that he intended the multi-volume history of the United States on which he had embarked at his death in part to explore when those acts of intellectual surgery in politics you’re referring to succeeded and when they failed.

DWL: Hofstadter understood postwar conservatism as fundamentally reactionary, motivated by fears of “moral laxity,” the decline of “entrepreneurial competition,” “the welfare state,” “urban disorders,” “bureaucracy”—as he puts it, the “whole modern condition” (“Goldwater & His Party,” 1964). This argument conflicts with more recent work on conservatism that emphasizes the economic self-interest of powerful private groups as a driving force for right-wing politics, as well as future-oriented ideologues bent on “liberating” the market. How well, do you believe, does Hofstadter explain the motivations and constituencies of postwar conservative and right-wing politics?

SW: It’s important to remember that between Hofstadter’s time and our own stands Reaganism, which was the outstanding political fact of the last quarter of the twentieth century into the twenty-first. The postwar conservatism Hofstadter described was engaged in a desperate fight against the New Deal and its immediate political legacy, which was still dominant—what Hofstadter referred to as “the whole modern condition.” In a sense, Hofstadter took liberal ascendancy too much for granted, although he clearly began to see things differently even as early as 1965. Reagan’s triumph hardly eradicated that liberal order, but it transformed the terms of politics: with some important interruptions, right-wing capitalism has been in the saddle for a very long time, and has hung on to its power in ever more radical ways since the 1990s.

One shortcoming of Hofstadter’s approach was to focus too much on ideology, which he ascribed to a mass of followers and a certain mass psychology. His writing was less attuned to the powerful forces and sometimes individuals who manipulated those resentments, sometimes quite cynically. McCarthyism, for example, showed a persistence of a certain conspiratorial strain, but it also had to do with a crisis inside Republican Party politics, pushed by elements that had no interest in “a conspiracy so immense” but thought they could exploit the upsurge. The same is true today, however, and not just in the United States. People expend a lot of time and ink trying to figure out the “populism” that has bred Trump, Brexit, and the rise of right-wing authoritarians on the Continent. But instead of mulling over the aggrieved factory workers who elected Trump, more attention ought to be paid to the elites who whipped up those resentful politics and thought they could exploit them. There’s still a book to be written on how the Republican establishment, including the Bush family, dug its own grave by thinking it could ride the back of the populist tiger. Anne Applebaum’s recent book on the threats to democracy makes this point very well.

DWL: Hofstadter does not let liberals off the hook in his writings. Paradoxically, he argues that the very moderateness of the Democratic Party in the 1950s and 1960s, with its “broad centrist position” (Ch. 4, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, 1965), encouraged radicalism in the Republican Party by making it “all but impossible” for moderate Republicans to develop an independent identity within the G.O.P. Moreover, he argues that postwar liberals were generally reconciled with big business and the “style of contemporary economic life” (Ch. 6, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, 1965), in contrast to conservatives who were eager for a restoration of small-scale competitive entrepreneurialism. How would you characterize Hofstadter’s relationship with Liberalism, both as a political philosophy and as manifested in the Democratic Party?

SW: Through the 1950s, Hofstadter was a fairly active pro-Adlai Stevenson Democrat. He saw Stevenson as the embodiment of an intelligent, even intellectual politics that could advance the post-New Deal order in a kind of reasonable progressive way. Between his renunciation of the Communist left in 1938 and his articles on Goldwater in 1964, his most public political stance came in supporting Stevenson’s candidacy in 1952, which actually got him into some hot water with the Columbia administration. He took Stevenson’s defeat by Eisenhower very hard. Indeed, I think there’s a way in which Anti-Intellectualism grew out of that disappointment. More broadly, he would fit under the now maligned category of Cold War liberal, although his own discomfort with labels, his own intellectualism, would have helped him see the contradictions as well as the fatuities in such groupings. Essentially, he was by temperament more of a private intellectual than a public intellectual—far more so, say, than his contemporary Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who reveled in party politics and power, and, to a lesser extent, another great liberal historian of the time, C. Vann Woodward. That is one reason his profusion of writing about Goldwater was so remarkable. He was truly alarmed by what he saw in Goldwater, and it roused him to action with the instrument he handled best, his typewriter.

All of that said, Hofstadter was too much the skeptic to think that post-New Deal liberalism had all of the answers, or even most of them. In the chapter you cite, for example, he notes with characteristic irony how some of the most fervent New Dealers like Thurman Arnold and A. A. Berle had become champions of big business, which they saw as now reined in by various countervailing forces, not least the federal government. A liberal, Hofstadter was always critical of liberalism, arguing from within. And so, he writes the following about the managerial class that emerged in corporate America, with its immense power, economic and political: “This class is by no means evil, or sinister in its intentions, but its human limitations often seem even more impressive than the range of its powers, and under modern conditions we have a right to ask again whether we can ever create enough checks to restrain it.” He goes on to write about how modern “urban mass society,” overseen by the liberal state, “is still not freed from widespread poverty and impresses us again and again with the deepness of its malaise, the range of its problems that remain unsolved, even in some cases pitifully untried.” This, I think, is Hofstadter at his best, seeing the danger of complacency in the face of human frailty, even (or maybe especially) in a liberal political order—a liberal Democrat who believed that liberalism and the Democratic Party could not survive without skepticism, without constantly questioning their own limitations.

DWL: Hofstadter’s writings have often served as fodder for political commentators seeking to make sense of right-wing politics in America today. His account of Goldwater’s ascent, for example, seems to mirror a number of other conservative victories in recent decades from the Tea Party to Trump. Many have invoked his arguments in discussing the political valence of populism, the purported psychological roots of partisanship, and the nature of both consensus and polarization in American politics. Nonetheless, Hofstadter’s explanations for American politics remain controversial, garnering accusations of elitism and cultural/psychological determinism. Indeed, by the late 1960s Hofstadter retreated from some of his earlier positions, stating to his editor that the arguments he had made in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963) failed to explain the social and political tumult of his country in the late 1960s. Looking back from 2020 rather than 1968, what are your own thoughts on the “utility” of Hofstadter’s work as it offers both explanations and prescriptions for American life and politics today?

SW: Hofstadter’s work remains not simply relevant but essential in our approach both to politics and to history. Without nuance and seeing things in degrees, without an aversion to sentimental or sensational seduction, without a certain humility as well as humanity, we are lost—and I don’t exactly see a surfeit of any of these either in our politics or in our writing of history. At times current historical work has become so strident, so polemical, disguising dubious claims in a kind of accusatory indignation, that it has reached the point of utter dullness and predictability.

Hofstadter’s impatience with sentimentalism, especially of the Popular Front variety, did lead him at times to be overly suspicious of popular movements; he would sometimes slight their rational political demands in a way that could sound elitist—more elitist than I think he intended. His close friend Woodward, for example, politely but forcefully took him to task for going overboard in his portrayal of the Populists as cranks tinctured by antisemitism. Likewise, his effort to link McCarthyism to the Populist tradition simply did not hold up. And there is some of that in Anti-Intellectualism. His dismissal, for example, of the beats, whom he derides as “beatniks,” and casts as merely destructive, anti-intellectual juveniles—the snooty attitude prevalent on Morningside Heights—shows how unprepared he was, even in 1963, for what we’ve come to think of as the genuinely creative forces of the 1960s. Still, by bringing front and center the darker side of popular movements, his was a necessary antidote to Manichean simplification and idealization.

I do think that Hofstadter, like many of his generation, came to take liberalism too much for granted, which was easy enough to do, say, in November 1964, when Lyndon Johnson crushed Barry Goldwater in a historic landslide. But he still believed that, even if defeated for the moment, the paranoid style had entrenched itself more than ever in our mainstream political life. And you’re correct, he came to have second thoughts about Anti-Intellectualism, a book with which he was never entirely satisfied. Hofstadter’s later work also deserves closer appreciation. His last complete book, on the Progressive Historians (1968), contains a critique of what had come to be known as “consensus” history, a term he always rejected. His compilation American Violence: A Documentary History (1970), edited with Michael Wallace, shows a renewed interest in the terms and techniques of American conflict. The chapters from what was going to be his grand history of the United States, published posthumously as America at 1750 (1973), contain passages about America’s origins as dark and visceral as anything out there today. Yet throughout he championed his idea of intellectualism, notably in his commencement address at Columbia in 1968. Coming as it did, after the University had let the campus revolt that spring get violently out of hand, that speech got quickly pigeonholed as some sort of “conservative” defense of the status quo. Read it again; I expect to include it in a subsequent volume. It is, in many ways, a fitting coda to Anti-Intellectualism and The Paranoid Style: “The possibility of modern democracy rests upon the willingness of governments to accept the existence of a loyal opposition, organized to reverse some of their policies and to replace them in office. Similarly, the possibility of the modern free university rests upon the willingness of society to support and sustain institutions part of whose business it is to examine, critically and without stint, the assumptions that prevail in that society.”

Daniel Wortel-London, Ph.D., (@dlondonnyu) is a historian of economic and political thought based in New York City. His dissertation, In Debt to Growth: Real Estate and the Political Economy of Public Finance in New York City, 1880–1973, examines how changing theories of urban economic development transformed American politics between the Gilded Age and the postwar era. His research, links to which can be found on his website, has been published in The Journal of Urban History, The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, and Dissent.

Featured Image: Featured Image: Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Uncollected Essays 1956-1965. Cover.