By Bennett Parten

On a visit to Philadelphia in the fall of 1841, a friend handed the African American abolitionist William H. Johnson a recently printed “Human Right[s] Circular” and asked for a response. The document had apparently called for a World’s Human Rights Convention, news the Pennsylvania abolitionist received with great enthusiasm. In his public reaction, published in The Liberator and addressed to fellow abolitionist Henry C. Wright, the circular’s probable author, Johnson claimed that such a convention was long overdue. “If the anti-slavery cause had been productive of no other good,” he wrote, “it has led to the inquiry of the nature of all those various relations of human beings, commonly known by the name of human rights.” Despite exciting “a deep and abiding interest,” these inquiries had, until now, been “very limited,” Johnson admitted, and he believed it was time to make the “equality of human rights… a great central, practical truth, and not a mere rhetorical flourish.” Such a “complex subject,” he told his friend and colleague, “was worthy the attention of the world.”

Much to Johnson’s dismay, the World’s Human Rights Convention went off like a lead balloon. It turns out that organizing a global conference designed to fight slavery and end oppression across the globe was harder than it first seemed, especially considering that its chief organizers were a penurious team of self-published writers, reformers, and itinerant speakers. As a result, the convention lived and died in a matter of months. The movement, well, moved, quickly setting its sights on new projects and ideas. Historians have thus only ever seen the World’s Human Rights Convention as a minor footnote within the history of a movement that never lacked for idealism and never stopped arguing long enough to pull off something of that order and magnitude. Yet even if only the germ of an idea, the planning of the World’s Human Rights Convention deserves pausing over, for it is perhaps the earliest expression of human rights thinking in American history.

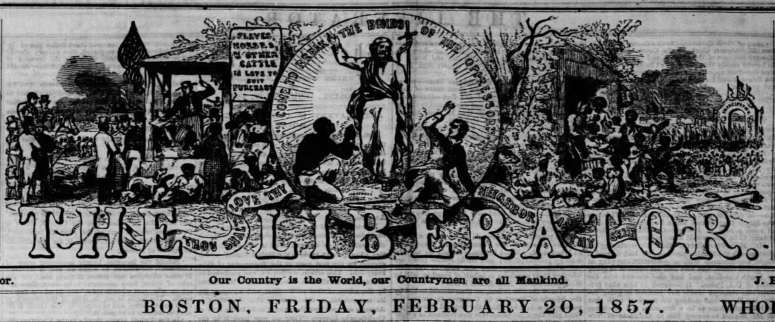

Understanding the convention requires understanding the abolitionist imagination from whence it came. Henry C. Wright, the mastermind behind it all, was many things: pacifist, anarchist, feminist, utopian. He was also a Garrisonian. So-named because of their leader and bespectacled editor of The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison, Garrisonains were the most radical anti-slavery faction of all. Their abolitionism was not “gradual”; it was “immediatist.” They were not just anti-slavery; they believed in racial equality. And as a rule, most Garrisonains were not just religious; they were Christian perfectionists, whose activism aimed at revolutionizing hearts and minds as much as ending slavery.

Most notably, to be a Garrisonian also meant hewing to a strict no-voting stance.

To vote, after all, was to effectively endorse a Constitution that enshrined the right to hold property-in-man. According to Garrisonian thinking, such a right made the Constitution illegitimate and evil, which is why Garrison himself once publicly burned a copy of the constitution and routinely referred to the document as “a Covenant with Death, an Agreement with Hell.” This refusal to vote has historically cast Garrisonians as little more than religious kooks and political cranks—men and women capable of moral indignation, but never effective reform. Historians have since rethought this position. Scholars now see the utility in the Garrisonian method, arguing that the no-voting stance allowed them to press the system from the outside and raise the public’s moral consciousness through abstention. Yet often lost in this discussion over means and ends is that the Garrisonian position stemmed from a particular political philosophy, the fundamentals of which formed the basis of a nascent vision for human rights.

This politics of Garrisonianism drew on two adjacent ideologies. The first was an ideology known as ‘non-resistance.’ An off-shoot of pacifism, non-resistance denounced any form of violence or coercion as contrary to the teachings of Christ. Garrison and his followers thus reasoned that since nations exist largely through their ability make war, it was therefore sinful to participate in electoral politics and associate with institutions capable of state violence in the broadest of forms. This commitment to non-resistance aligned with a corresponding ideology known as “comeouterism.” Drawn from the perfectionist teachings of John Humphrey Noyes, leader of the Oneida commune, a socialist utopian community in upstate New York, “comeouterism” held that Christians should try and perfect their world as if the Kingdom of Heaven had already arrived. To do so required that believers “come out” of institutions that failed to meet this ideal, which prompted Garrisonians to disavow religious organizations with any taint of slavery, denounce the U.S government, and condemn that “covenant with death” known as the Constitution.

Although it never came together, the attempted organizing of the first ever “World’s Human Rights Convention” was the result of Garrisonians extending their faith in both ‘non-resistence’ and ‘comeouterism’ into the realm of rights. As historian W. Caleb McDaniel has argued, the convention rested on the Garrisonian belief in the degeneracy of nation-states—a conviction that ultimately led Wright to renounce his “nationalism” in favor of the “high and heaven-erected platform of HUMAN BROTHERHOOD” (113-115). The planned convention encapsulates this anti-statist vision for human rights in three important ways. First, the convention was truly global in scope. “Better than Congress of nations, it would be a Congress of humanity,” wrote Maria Weston Chapman in a separate response. Like most Garrisonians, Chapman saw herself as a citizen of the world and viewed the convention as a means of making good on the famous Garrisonian mantra: “Our Country is the world, our Countrymen are all Mankind.”

Second, when it came to human rights, the Garrisonians knew they had to establish a credible foundation before proceeding ahead. This meant deciding not only what human rights were, but inquiring into the “causes of their violation” as well as “the means of their restoration and protection.” Chapman hoped that the convention would eventually become an annual body, and Wright himself imagined that the convention would evolve into a standing tribunal, which would hear and try cases of human rights abuses from around the world. The point is that they imagined the convention as the first step in establishing a global counter to national authority, an institution that might parry away and correct the sins of the state.

Lastly, the Garrisonians made this rejection of state citizenship and national allegiance the central precept behind the entire convention. “In our estimate of man’s relations, rights, duties, and responsibilities, geographical lines and national boundaries must be set aside,” wrote Wright, for as he put it: “Human love is not bounded by longitude or latitude.” Drawing on his commitment to non-resistance, he then went on, “We [the convention] would meet, not as States and nations, to talk about national rights, but as the human race, to consider human rights.” As he explained, he imagined the convention as one where a claim to “HUMANITY” would be the “only certificate of admission, the only wealth, the only badge of honor, the only patent of nobility.” “In the name of humanity,” he concluded in typical Garrisonian gusto, “let us unfurl, in the sight of all nations, the banner of HUMAN RIGHTS…Let us demand an instant, a perfect, practical recognition of human rights and human equality.” He never managed to unfurl this banner on a global stage; Philadelphia was about as far as his message would ever reach.

The irony of it all, so to speak, is that the Garrisonians had the right string but the wrong yo-yo. While there is something identifiably modern in their rights thinking, high-minded rights talk was not what ended slavery in America. Ending slavery required elections, it required bullets, and it required mobilizing the full force of the American state, for emancipation came amidst a terrible civil war, which saw the federal government exercise its war powers to enact military emancipation, the largest liquidation of property in American history. In short, the forces Garrisonians set their rights vision in opposition to were the same forces that paradoxically clinched the future they longed to achieve. The greatest weapon in the war against slavery, it turns out, was never the abstract dream of human rights, but rather the raw, unvarnished tools of state power.

This otherwise tragic paradox speaks, in part, to why the World’s Human Rights Convention drifted off into obscurity. It also helps us understand why American abolitionism has a somewhat perplexing place in the history of human rights: it was a brief burst of energy and ideas soon eclipsed by massive armies fueled by the power of the federal state. Most of all, however, this paradox captures just how rooted, how gargantuan, and how fixed of a problem slavery was and how both it and its abolition shaped the nineteenth century and thus American’s entry into the modern age. Its shadow—as dark and bloody as it is long—extended into the twentieth century and has followed us here, still haunting us from the grave.

Bennett Parten is a PhD student in 19th century US history at Yale University.

Featured Image: The Liberator, February 20, 1857.