By Jonas Knatz

Rüdiger Zill is a philosopher and program manager at the Einstein Forum, Potsdam. He works on intellectual history, theory and history of emotions, and aesthetics. His most recent publications include Der absolute Leser. Hans Blumenberg: Eine intellektuelle Biographie (Suhrkamp, 2020), Poetik und Hermeneutik im Rückblick. Interviews mit Beteiligten (co-edited with Petra Boden, Fink, 2016) and Metapherngeschichten. Perspektiven einer Theorie der Unbegrifflichkeit (co-edited with Matthias Kroß, Parerga, 2011).

Contributing editor Jonas Knatz interviewed him about his work on Hans Blumenberg.

Jonas Knatz: In 2017, Paul Fleming noted that “a Blumenberg renaissance is taking place in the United States.” (119) And there is ample evidence that this trend has not come to a halt yet: Last year, the Journal of the History of Ideas devoted a special issue to the 50th anniversary of The Legitimacy of the Modern Age, this blog organized a forum on Hans Blumenberg and political myth, and a new translation of Blumenberg’s central writings was just published with Cornell University Press. This trend in North American academia mirrors the renewed interest in Blumenberg’s philosophy in Germany which, spurred by this year’s centennial of the philosopher’s birth in Lübeck, saw the publication of numerous new books and articles. What motivated your own work on Blumenberg and how would you explain this increased attention to his philosophy in both Germany and the US?

Rüdiger Zill: My own interest in Blumenberg’s work was sparked by my dissertation on models and metaphors. My idea was to bring thinkers from different countries who try to explain the power of metaphors into conversation with one another and thereby to transgress national and cultural barriers: German thinkers were very late in their reception of English and French theorists (Anselm Haverkamp’s edited volume Theorie der Metapher from 1983 was a milestone in this regard), and the English speaking world was (and still is) not very familiar with German approaches either. Just one recent, surprising example: even a philosopher like Charles Taylor, someone very familiar with the German philosophy of language, completely ignores Blumenberg in his book The Language Animal (2016), despite the proximity between his central idea of significance (translated as “Bedeutsamkeit” in the German edition) and Blumenberg’s concept of rhetoric in general and his theory of the absolute metaphor in particular.

Starting with the Metaphorologie, I began to familiarize myself with Blumenberg’s other books, and when I discovered his unpublished papers in the Marbach archives in 2008, it was clear to me that they provided us with an extraordinary opportunity to observe a thinker at work. These papers include not only a huge bulk of unpublished manuscripts (some of which have been edited and published in the meantime) but also the instruments of Blumenberg’s thinking, a minute self-documentation which provides information not only about the books he read (including the exact date and sometimes his rating), but also about which part of his manuscripts he worked on what day. There is also, of course, his Zettelkasten (card box) with quotes and remarks. In short, the archive provides a glimpse into Blumenberg’s machinery of thinking. I became fascinated by the idea that he not only constitutes an important subject in the history of science, but could also be turned into its object: his papers open up important insights into the fabrication of ideas. So, I combined the perspective from within (his theory) with the view from outside (his modus operandi).

The more I got to know about his work and its driving forces, the more I got the feeling that a number of misinterpretations shape our understanding of his philosophy. But only in 2016, when I happened to be part of the crew of Christoph Rüter’s documentary Hans Blumenberg – Der unsichtbare Philosoph, did I begin thinking about adding a biographical dimension to my work on his philosophy.

Blumenberg was not really a big name during his own life-time. Of course he was known and extremely respected by his colleagues, which is exemplified by how his fellow members in the research group “Poetik und Hermeneutik” initially paid court to him. His lectures in Münster were extremely popular and drew a broad audience that also included his colleagues and a philosophically interested public, and he was known for his essays in the newspapers Neue Zürcher Zeitung and Frankfurter Allgemeine. But he was far from being a preeminent figure. His books sold well but were rarely read: too many pages in his very ornate style. Actually, only the later books that were smaller, like Shipwreck with Spectator, Care Crosses the River and Matthäuspassion, won over a wider readership.

Only after his death did he become an object of growing fascination, a process spurred on by a host of posthumous publications: compilations of his shorter essays as well as impressive studies on general topics like Description of Man. Now everybody could see what the well-informed circles in Münster had known already: the breadth of his work’s scope. And this process is far from being finished, we still are witnessing the rise of a new continent of ideas.

And this is why his reception in the United States is in its infancy. Some of his most important works were already translated during his lifetime, such as the Legitimacy of the Modern Age (1983), The Genesis of the Copernican World (1987) and Work on Myth (1985)—but these books constitute huge thresholds for readers. The smaller books, which are easier to approach, were initially not translated; Paradigms of Metaphorology (orig. 1960) made its way into the English-speaking world as late as 2010. But at least partly, Blumenberg himself is to blame for this as well. In the 1980s, he turned down a plan by his translator Robert Wallace to publish an English volume with articles on metaphorology and rhetoric. Blumenberg rejected this idea because he felt that his older texts like Paradigms were insufficient, and that an English translation should start with a reformulated version of his metaphorology. This reformulation happened exclusively in German and remains unfortunately incomplete: in 1979, Blumenberg published Schiffbruch mit Zuschauer (Shipwreck with Spectator, translated by MIT Press only in 1996), followed by Die Lesbarkeit der Welt (The Legibility of the World, still untranslated). Therefore, I am not sure that Blumenberg’s work enjoys a renaissance in the United States today: for the most part, it seems to be more of a first encounter.

But there are obstacles to the continuation of this trend. On the Anglophone book market and in the North American discussion about European philosophy, Blumenberg’s oeuvre resists easy integration. He was far away from the new French philosophers, and even from German thinkers who are well discussed on the other side of the Atlantic, such as the Frankfurt School. This is why he is approached via other thinkers like Hannah Arendt or Carl Schmitt, household names in American cultural theory that, however, were far less important for Blumenberg’s own intellectual life than we are made to think. And when it comes to philosophy proper: there is no way to bridge his philosophical writings and analytical philosophy; even in Germany Blumenberg’s texts are more often found in literary and cultural studies or among theologians than in philosophy departments.

JK: You specifically chose to write an intellectual biography of Blumenberg—a genre which, as you write in your prologue, poses the methodological challenge of determining the link between text and context. The resulting work, titled The Absolute Reader, is split into three parts, of which the first offers a description of Blumenberg’s life while the third traces the process of his philosophical development. Why did you choose to pursue a clear separation between Blumenberg’s private and his philosophical life? And why did you decide to approach his philosophy in the form of an intellectual biography?

RZ: Of course, there is no clear cut between private life and philosophical development. Even in the first part—where I am dealing with his biography in the narrow sense—I had to include theoretical anchors, sketches of representative texts. Conversely, there are also links to Blumenberg’s political and social situation in the third part, because his ideas respond at least in certain respects to their non-theoretical context. One of the central texts I interpret in part III is Blumenberg’s 1949 talk “Philosophy Facing the Questions of our Time” (“Philosophie vor den Fragen der Zeit”), and of course he is not referring to quantum theory here but to political and moral challenges. These sketches are junctions, connecting points.

Still, some people think this separation is artificial. Jörg Später, for example, the author of an exceptional and very successful biography of Siegfried Kracauer, wrote that reading my book felt like first watching a film without the soundtrack, then listening to the soundtrack on its own, and afterwards reading the script. And of course, if you want to understand Blumenberg and his work, you have to eventually combine these strands.

Nevertheless, I am convinced that there are some good reasons for using this “tripartite” structure. If you ask what determines the development of a theoretical corpus, you always encounter different forces of influence. Certainly, in the case of philosophy, personal experience plays into it, for it is not physics or any other highly abstract science: it is nurtured by the “questions of the time,” political, social, historical or even very personal circumstances. Being a student in the second half of the 1940s in Germany meant dealing with the recent past. But then experiences and questions are one thing, and intellectual instruments to answering these questions are quite another. What kind of theory is at hand to deal with these questions? What is within the horizon of a 25-year-old student who grew up in a basically National Socialist surrounding, influenced by the then-prevalent ideas, but who also had to suffer prosecution and even hide for some time? What are the philosophical tools he encountered up to this point? These intellectual instruments have their own history and their own logic. So, personal and historical experience is one thread of determination, the theoretical options of response is another. Biography and history of ideas are connected but should not be conflated. There is always the pitfall of writing a caricature of intellectual history: it is rarely missed to mention that Blumenberg, the author of a book titled Cave Exits, had to hide at the end of WW II in a secret room. But what does this really explain?

Apart from following these two threads, I wrote a shorter second part on Blumenberg’s art of thinking and writing, his actual method of producing texts, the kind of philosophy in action that you can study in his papers. And I think it is important to realize that Blumenberg was a playful mind; he experimented a lot with his texts, not only producing articles and books from the material that was originally collected in the card boxes, but also formulating and reformulating certain ideas, arranging and rearranging piles of text. And again: this, too, developed its own logic, not to be explained as the result of a prefabricated plan.

What I wanted to show is that we can only understand a corpus of philosophical texts as the result of these three interacting lines, which nevertheless are governed by respective internal logics that have to be sketched out separately. But I have to confess: this approach to Blumenberg’s work was not a given when I started the project but in itself became the result of a longer experimental engagement with Blumenberg.

JK: Already in its mere form, an intellectual biography of Blumenberg challenges the prevalent public image of the German philosopher as a recluse writer—a myth that your book tries to dispel by showing Blumenberg’s long-standing attempts to become a public intellectual as well as his active role in shaping Germany’s post-WWII educational landscape. You argue that Blumenberg’s withdrawal from public life, which starkly shaped his public image, occurred only at a very late stage in his life. What motivated his exit from the public sphere?

RZ: Blumenberg’s public life follows the movement of a hyperbola, with the years in Gießen und Bochum in the 1960s marking its climax. What motivated his exit, his withdrawal from the public sphere is difficult to say—we can only guess and follow some hints he left behind. Blumenberg was already 45 when he published his first proper book, Die kopernikanische Wende, in 1965, basically a compilation of older articles he had previously published in the journal Studium generale. Up to this point, he was fighting with the complexity of the material, at least if we choose to believe what he says in some letters to his colleagues. But he was convinced that he had a lot more to say and that he was running out of time, lifetime. And indeed, from this point onward, he published a number of big books.

This perceived shortage of lifetime was accompanied by a feeling of suffering failures. He was disappointed by the results of interdisciplinarity, in particular within the research group “Poetik und Hermeneutik,” and by his unsuccessful attempts to take part in the process of German universities. He felt rejected by his colleagues in the philosophy department in Münster, obstructed by the academic administration, and harassed by the student movement, which in part reminded him of the Nazis in Lübeck. So he increasingly yearned for reclusion and, in the end, hardly left his house. After his retirement, he was eager, as he said, “to bring in the harvest,” which in his case meant to arrange his papers, sometimes to rewrite parts of the manuscripts, and to prepare them for future publication by somebody else. That there would be someone doing this, this he was convinced of.

JK: Judging from your biography, Blumenberg seems to have had a very complicated and ambivalent relationship with Germany and particularly its National Socialist past. In 1939, he was removed from the position as a valedictorian because of his Jewish mother. At the same time, the valedictorian speech, which he had already drafted and which was subsequently given by one of his classmates, constituted an attempt to philosophically reconcile humanism and National Socialism. In addition, on May 8, 1945, the day of German surrender, Blumenberg read Ernst Jünger’s Storm of Steel, only days after the British invasion of Hamburg allowed him to leave his hideout and months after he was coerced into forced labor. In 1996, he wrote to Uwe Wolff, a former student of his, that Germany had never stopped being “uncanny” for him because “nothing has evaporated that made Hitler possible.” But here again, he refrained from openly criticizing philosophers that had been implicated in National Socialism, such as Carl Schmitt or Erich Rothacker. Instead, when he attacked them for their support of National Socialism, he disguised his critique as a debate about secularization in the, as Falko Schmieder has argued, “political Nirvana of late Medieval gnosis and its second overcoming.” In his review of your biography, Micha Brumlik suggests that Blumenberg’s philosophy can partly be understood as a “work of suppression,” written by someone who has been heavily traumatized by his persecution under National Socialism. How would you characterize Blumenberg’s thought about National Socialism and its afterlife in the Federal Republic?

RZ: Here again, Blumenberg’s “thought” was changing over time. The uncanniness he mentioned in the letter to Uwe Wolff and in other letters as well is a feeling of his later years. When he tried to convince Hans Jonas to accept a professorship at Kiel University in 1955, which for Jonas would have meant to re-migrate from the US to the country which had sent his mother to Auschwitz, Blumenberg was convinced that “the political development of the Federal Republic, the successful overcoming of the ideological remainders of the horrible past” would allow for a new judgement on whether or not “people of your and my personal and familial fate” could gain “a positive sense of life” in Germany. And his own judgement was affirmative.

I don’t think his point of view in the secularization debate was a critique of National Socialism in disguise. He certainly knew about Carl Schmitt’s past, but he refused to be the “Last Judgment,” and with Erich Rothacker he felt some kind of friendship and even admiration as we can see from the obituary he wrote for him in 1966. Hermann Lübbe reported that Blumenberg was not interested in the personal past of his contemporaries but in their present-day behavior. If they had believed in Hitler before 1945, he did not waste any words about it, but he was extremely alert if somebody remained a Nazi after.

I try to use the concept of “resonance” in my book, in the sense that past and presence resonate with each other. “Resonance” is different from “reaction” or even “echo,” it isn’t something that simply responds to a past experience (let alone a psychological effect of a former cause), but a new experience that chooses some older experience (from a number of possibilities) because it fits the present one. As soon as Blumenberg felt rejected by his colleagues and other people, he began to reevaluate his past. And so the past experience explains, substantiates, empowers the present one. It is a process of going back and forth.

JK: In his obituary of Blumenberg, Odo Marquard wrote that the former’s philosophy follows a leitmotif: the attempt of the weak yet creative human subject to gain distance from the burdensome and reckless absoluteness of the real. This assessment has been very influential for Blumenberg’s reception and has featured prominently in introductory texts to his philosophy. Your book cautions against such a systematic reading and, by contrast, argues that his philosophical oeuvre has to be understood as the outcome of an evolving, experimental and restless thought process that followed an immanent movement and responded to external developments. It was also characterized by shifts. Most importantly perhaps, over the course of the 1970s, Blumenberg shifted from an early focus on the history of science, technology and metaphors, to anthropological topics. What was the immanent logic behind this shift in attention and how did it correspond to external events?

RZ: I would say that the turning point occurred in 1970, when Blumenberg left Bochum for Münster. In 1971, he published his first explicit article on anthropology, An Anthropological Approach to the Contemporary Significance of Rhetoric, in an Italian journal. Of course, he read books on anthropology much earlier, including Arnold Gehlen’s Der Mensch, which he studied already in the 1940s. He was interested in anthropology and even gave talks on it throughout the 1950s. But still, when Gadamer invited him in 1968 to contribute an article to his encyclopedia on Neue Anthropologie, Blumenberg refused to do so, arguing that he felt not yet prepared. His main work on anthropology took shape in the second half of the 1970s, the results of which were edited and published by Manfred Sommer in the 2006 book Beschreibung des Menschen.

Some scholars argue that Blumenberg’s work has been saturated with anthropology from its inception. The question eventually comes down to our definition of anthropology, and German “Anthropologie” is different from English “anthropology.” If anthropology means human self-description and self-interpretation, in particular the historical search for self-assertion (Selbstbehauptung), then of course all of Blumenberg’s approaches from the early beginning onward are part of anthropology. But if anthropology is a theory that seeks to explain the conditio humana through its biological constitution and in particular with reference to its evolutionary beginnings, a theory that investigates the human struggle for self-preservation (Selbsterhaltung) and inquiries into the difference between humans and animals, anthropology becomes central for Blumenberg’s philosophy only after 1970. (By the way: this second definition dominated German “Anthropologie” for a long time.)

At the beginning of his career, Blumenberg was interested in the history of science and technology, the practical ways of dealing with the world, and in particular the intellectual and mental predispositions that were necessary for certain inventions and developments. Similar to Max Weber’s search for the religious roots of capitalism, Blumenberg was interested in the philosophical and cultural premises that made human self-assertion possible. Here, the shift from the Middle Ages to Modernity was decisive for Blumenberg, as it was in this moment that science became independent from world-views and gained its own momentum. After that, progress became exclusively the result of inner-scientific developments. After publishing The Legitimacy of the Modern Age and Genesis of the Copernican World, he probably had the impression that there was nothing left to be explained in this decisive period. For all further developments, he had to change his profession. The histories of contemporary physics or astronomy are not explicable with reference to their philosophical foundation, but require attention to extremely intricate inner-scientific problems, and he was certainly not trained for that. In addition, the history of modern technology began to be dominated by Marxist approaches. Although he made very sophisticated contributions to the discussion about their materialist claims, he probably no longer wanted to deal with something that he felt uncomfortable with.

So he started with a “deeper” layer of the human condition, something which seems to be beyond historical development. At the same time, he also started with the reformulation of his metaphorology as a theory of non-conceptuality, a reevaluation of rhetoric that traces the mechanisms of significance (Bedeutsamkeit), free of its practical applicability and exploitability.

JK: In 1983, Richard Rorty wrote in his review of The Legitimacy of the Modern Age that Blumenberg “turns Heidegger’s story on its head, but does not fall back into the totalizing metaphysics which backed up Hegel’s story” – a form of philosophy he characterized as “good old-fashioned Geistesgeschichte, but without the teleology and purported inevitability of the genre.” With its analysis of the epochal change in the 16th century, Rorty argued, Blumenberg’s books resemble Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions(1962) and Michel Foucault’s Les Mots et les Choses (1966), both of which were published around the same time. What do we know about Blumenberg’s reading of non-German philosophy and these two authors in particular? And how would you distinguish Blumenberg from them?

RZ: It is difficult to say anything about Blumenberg’s general reception of non-German philosophy. Of course, he had a wide horizon, but in certain respects his readings were limited. He definitely was not much interested in Anglo-Saxon analytical philosophy, contrary to colleagues such as Dieter Henrich or Jürgen Habermas. But he knew Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and even included it in his list of recommendations for Suhrkamp’s then-new series “Theorie,” to which he was a scientific advisor (alongside Habermas, Henrich, and Jacob Taubes). When it comes to French philosophy, he certainly read Sartre as a young man and also knew Merleau-Ponty’s writings. But he was not familiar with the “new French theory,” except for some rather occasional reading of Foucault. He mentioned Foucault’s postface of Flaubert’s Les Tentations de saint Antoine in his Die Lesbarkeit der Welt (p. 305–309). And he also read the first volume of The History of Sexuality but was upset about it; he even called it a “poor and ridiculous piece of very little content” (“dieses inhaltsarme und läppische Machwerk”). I did not find any evidence that he had read Les Mot et les choses. So we can only guess what he would have said. I think there is one big difference between Blumenberg and Foucault (or even Kuhn): while Foucault emphasizes rupture, Blumenberg was interested in transitions. He always asked for the epochal threshold and what drove people to change their world views. But of course, a closer comparison between these three authors would be interesting. A very early attempt to do that was made by the late historian Heinz Dieter Kittsteiner in his book Naturabsicht und Unsichtbare Hand (1980).

JK: In some aspects, Blumenberg’s philosophy in its attention to the ‘non-conceptual’ resembles Theodor W. Adorno’s Critical Theory. He also attentively read Adorno and, as you point out in the book, devoted one of his few lectures about contemporary philosophers to the Negative Dialectics despite being associated with different philosophical circles in Germany. How would you describe Blumenberg’s relationship to the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt?

RZ: In general, there was no relationship to the Institute for Social Research as such, or to people associated with the project of Critical Theory, apart from very few exceptions. For example, he met Siegfried Kracauer at the colloquia of the “Poetik und Hermeneutik” group and subsequently corresponded with him, among other things about the notion of history. There was some basic agreement, but unfortunately Kracauer died very soon after this correspondence began. Blumenberg’s relationship with Adorno is on first glance entirely critical (Christian Voller called it “communication refused”). Whenever Blumenberg mentioned or quoted Adorno, he either dismissed him or made fun of him. In a posthumously published fragment (»Die Suggestion des beinahe Selbstgekonnten«), for example, he ridiculed Adorno’s style: “Nobody got Adorno, but, after a few pages, everybody understood how it is done. Mannerisms grant success to the extent that they turn into parody—and this then looks like a successful reception.” (p. 89) [1]

But in his only letter to Adorno, Blumenberg concedes that he discovered “amazing parallels” between their respective thinking. And indeed, both re-evaluated rhetoric and were extremely suspicious towards the concept of identity in general and definitions in particular. Take for example a line from “An Anthropological Approach to the Contemporary Significance of Rhetoric,” where Blumenberg writes: “Predicates are ‘institutions’; a concrete thing is comprehended by being analyzed into the relationships by which it belongs to these institutions. When it has been absorbed in judgments, it has disappeared as something concrete. But to comprehend something as something is radically different from the procedure of comprehending something by means of something else.” (p. 189). This line emphasizes that human self-reference is metaphorical, but it also resembles very much Adorno’s dictum that “the incommensurable is cut away.” Another interesting question is: Did Blumenberg read the Dialectics of Enlightenment, and is his Work on Myth a hidden response? There is no clear evidence for this, no trace of Horkheimer’s and Adorno’s book in the reading lists or in any other text of Blumenberg’s, except for one file card in his Zettelkasten that contains a quote from the Dialectics. But this could be something he had found quoted in a text by a third author. But again: This is something which is worth investigating. Sebastian Tränkle wrote his dissertation on the relation between Adorno and Blumenberg, I think it will be published at the end of the year.

Another question is Blumenberg’s relation to Habermas, whom Blumenberg of course knew. He definitely read articles by Habermas but paid very little attention to the latter’s books. Ferdinand Fellmann, one of Blumenberg’s assistants since his early years in Gießen, was the first to compare Habermas and Blumenberg at the end of his book Gelebte Philosophie in Deutschland (1983).

JK: You explicitly state in your book that an intellectual biography can hardly address questions about the topicality of Blumenberg’s philosophy. But do you think Blumenberg should be read at the moment—and if so, where should we start?

RZ: Of course, it would not be of any interest to write the biography of a philosopher whose work is outdated or boring or overestimated. To the contrary: Blumenberg’s oeuvre is so rich that the question of where to start necessarily has more than one answer. It all depends on your interests: metaphorology, theory of myth, history of science or anthropology, to mention only the currently liveliest debates connected to Blumenberg’s work. Felix Heidenreich just published the book Politische Metaphorologie. Hans Blumenberg heute, in which he explicitly asks whether it is possible to use Blumenberg’s ideas as tools for our own questions. His main example is metaphorology, which is probably the field where Blumenberg’s name is most prominent, and which is closely linked to the theory of myth. Is it possible to understand contemporary political myths with Blumenberg? I think this question merits attention.

I also believe that it is still worth reassessing Blumenberg as an intellectual historian. We have to read the Legitimacy and the Genesis again. I personally think that it is less fruitful to work with the anthropological approaches of his later years, at least if they are understood as anthropology in the narrow sense. The evidence Blumenberg relied on was, even in his days, fairly outdated. It is a kind of “speculative anthropology” that is supposed to produce significance (Bedeutsamkeit) for the present situation, but without the detailed historical investigations that characterized his earlier books. It is less informative as far as the genesis of the human being is concerned. But I have to admit that most of Blumenberg’s readers would not agree with me in this respect. They consider the anthropology his most interesting intellectual legacy.

Apart from that, you can read Blumenberg for his literary qualities and start with his smaller essays. There, you will find a lot of unexpected observations, for example on the question of immortality, on boredom or on visibility.

But whatever part of his philosophy (and there are many more to be discovered) you prefer, there is a general characteristic in Blumenberg’s work: it is “narrative philosophy.” I think this is a very productive concept, although he himself used it only occasionally. Sometimes he used “concepts in (hi)stories” (Begriffe in Geschichten). In agreement with traditional Begriffsgeschichte, he stresses the importance of the historical context—that we cannot just define concepts as we like (be it in science or politics), but that we have to understand them as result of their genealogy and their respective milieu. This is completely different, for example, from the theory of metaphor proposed by Lakoff and Johnson.

But narrative philosophy reaches further still: although Blumenberg was aware of the fact that we can no longer produce universally shared and binding world views, he nevertheless knew of the importance of pragmatic narratives to interpret the world, narratives that help us to cope with the world beyond (but not contrary to) practical transformations via technology and science. Modern philosophy very often tries to reduce our relationship to reality to particular moral or cognitive questions and looks for answers in a way that mirrors the natural sciences. But there is always something left unexplained, and this is what Blumenberg was after. This is why Richard Rorty, who knew but a small portion of Blumenberg’s early books, saw him as an ally: even if they are in part speculative, we need narratives, alternative narratives to deal with the world. But unlike Rorty, Blumenberg knew that this is something we can only develop in reflection on the history of our own thinking.

[1] [German original: „Keiner hat Adorno verstanden, aber alle haben nach wenigen Seiten kapiert, wie man es macht. Manierismen liefern Erfolg im Maße ihres Aufreizens zur Parodie—und das sieht dann aus wie die gelungene Rezeption.“]

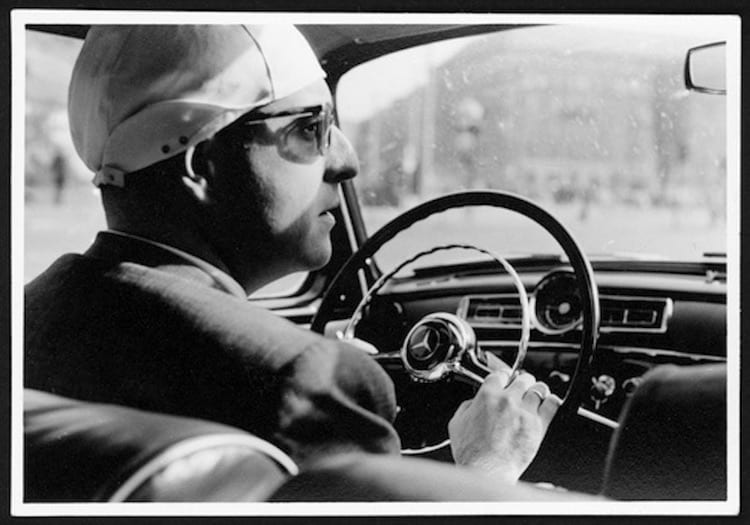

Featured Image: Hans Blumenberg driving a Mercedes, 1958. ©Bettina Blumenberg, courtesy of Suhrkamp