By Lesa Redmond

It is an exciting time to study the connection between universities and slavery. In the past two decades, scholars have taken up Craig Steven Wilder’s charge in Ebony and Ivy to uncover “the influence of slavery on the production of knowledge and the intellectual cultures of the United States” (10). The resulting research dispels any notion of the objective pursuit of knowledge on college campuses. Slavery defined what colleges could and could not do, whom they could and could not enroll, whom they would and would not hire; it defined what faculty could and could not say, and it defined what students should and should not think.

Strangely, for all this talk about universities and slavery, scholars rarely talk about Black intellectual contribution. Black bodies are certainly present in the literature—in their sale to supplement college financials, in their labor that constructed college campuses, and in their very existence that formed the foundation for a heinous science of race. Yet, undergirding all such scholarship is the assumption that enslaved people, in so laboring, were not intellectually productive. Rather, their sole contribution to the “intellectual cultures of the United States” came in the form of their bondage. In this essay, I aim to uncover the other half of the intertwined histories of universities and slavery. In doing so, I hope to establish that those enslaved produced knowledge of their own and changed America’s higher education landscape as a result.

To answer the question of Black intellectual contribution in higher education, I take George Moses Horton’s life and career as a starting point. For roughly half a century, from around 1815 to 1865, Horton travelled the eight-mile distance from his slaveholder’s home in Chatham to Chapel Hill, North Carolina. While there, he interacted with students, administrators, and professors. He sold fruit first and acrostics (a style of poetry) later on. He delivered speeches on demand for students and, twice, was invited to deliver a formal oration. Horton learned to write in Chapel Hill. Under the instruction of Caroline Lee Whiting Hentz, wife of professor Nicholas Hentz, he perfected his poetical craft. Horton garnered the vast majority of subscribers to his second book of poetry, The Poetical Works of George M. Horton, the Colored Bard of North Carolina, from the University community. Although he gained national recognition for his poetry and attempted to use the money from his books to contribute to his manumission, Horton remained in bondage for the duration of his time at Chapel Hill and, indeed, for most of his life.

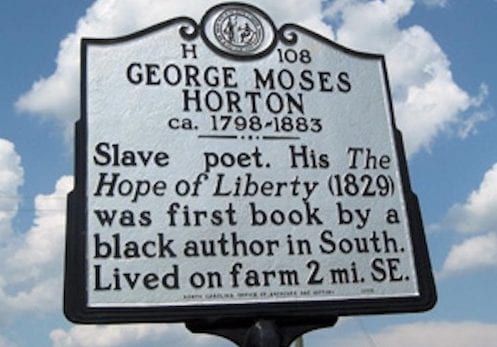

All things considered, Horton’s life is well documented and well discussed. Commemorative plaques (and even a dorm) recognize his unique position as an enslaved literary giant—a self-styled Black Bard, and the first enslaved person to have a published book of poetry in the South. In the literary field, scholars have most often and most thoroughly asked questions about the content of Horton’s poetry. Across his three published works, one finds poetry broaching subjects such as love, death, patriotism and, occasionally, slavery. Whether you interpret his verse as a commentary on the South’s natural world through the eyes of a slave, or as a redefinition of temperance, public space, and freedom, suffice it to say that Horton’s career sheds light on what it means to compose literature in bondage. Not everyone has taken Horton’s contributions to American literature seriously (see, for instance, Richard Walser’s The Black Poet), so such scholarship is important because it places Horton in conversation with his peers. What has been understudied, however, is Horton’s life not only as a poet, but also as a scholar and active participant in the University of North Carolina’s intellectual community. What did he learn from Chapel Hill students? What did they learn from him? And perhaps most importantly, how does the character of knowledge change when it is produced on uneven terms?

What is clear from Horton’s time in Chapel Hill is that in this environment he learned how to marry physical labor with intellectual labor and make a profit from both. In truth, Horton’s manual and intellectual work grew in tandem well before he stepped foot on campus. In the preface to his 1845 book of poetry, Horton narrates how he learned to read. He describes the collaborative effort launched between himself and his mother, brother, and white school children in his vicinity. He outlines the depths of his determination to read: he would “sit sweating and smoking over my incompetent bark or brush light, almost exhausted by the heat of the fire, and almost suffocated with smoke” so that he could steal glances at spelling books during the only free time he had available at night (iv-vi). Thus, starting from age ten, Horton became well versed in working and reading, and reading and working.

When Horton started selling acrostic poetry for students’ love interests at the University of North Carolina in 1815, it was the first time he was able to earn money for the intellectual labor he undertook. At Chapel Hill, Horton found a community that did not preference his physical ability over his mental ability. In fact, when reflecting upon his time at the University, Horton mentions his physical labor only once when explaining how his acrostics for students were “composed at the handle of the plough” (The Poetical Works, xiv). This contrasts starkly with the description of his time in Chatham on his slave owner’s farm. He talks openly of his disdain for work as a “cowboy” for William Horton, how he and his fellow bondsmen preferred to drink to excess over “assist[ing] a prudent farmer in cultivating a field for the space of an hour,” and how his owner “carried me into measures almost beyond my physical ability” (xii).

At Chapel Hill, however, Horton recalls the intellectual labor he did for the students. I use intellectual labor here because, simply, Horton was paid for his acrostics. Looking beyond this monetary transaction, Horton paints his dealings with students and administrators as a professional endeavor. He learned to claim ownership of, and take pride in, the products of his work at Chapel Hill. He learned to brag about his “spark of genius” and the fame it garnered him. In addition to tangible profits, Horton’s intellectual labor also earned him a place within a network of scholars. To be sure, his membership within this network was limited. He would have witnessed how those enslaved around him could be forced to construct college buildings or be hired out to students. In his preface to the Poetical Works, Horton explains how he witnessed his fellow bondsmen being freely “pranked” for the amusement of young college boys. From such instances, Horton learned his ‘place’ within this network at the University. Simultaneously, through his personal interactions with students who purchased his acrostics, who provided him with books to further his learning, and who spread the word about his genius, Horton learned the value of white sponsorship at the University of North Carolina.

But knowledge is not unilateral. Just as Horton learned an immense deal from his white associates, so too did they learn from him. They learned the extent to which they could exploit Horton’s intellectual labor. Students originally intended to belittle Horton by insisting that he “spout,” or deliver short impromptu speeches on demand. Their plans soon clashed with Horton’s own designs. Horton describes how he “abandoned my foolish harangues, and began to speak of poetry, which lifted these still higher on the wing of astonishment; all eyes were on me, and all ears were open” (Poetical Works, xiv).It is clear that he engaged with students on his own terms. Horton’s young proprietors got used to “all eyes and ears” being on him. After all, for many years, carefully listening to this enslaved man was the only option they had for transcribing his oral acrostics into written gifts for their sweethearts. In 1859, Horton delivered his Address to the Colligates of the University of North Carolina. In doing so, he inspired at least two students to lend him their undivided attention for an extended period of time so that they could transcribe twenty-nine pages of his speech. We can perhaps see this speech as an example of students yet again mocking Horton by encouraging a lengthy oration. Or, we can choose to see it as part and parcel of similiar college orations at the time where, as Al Brophy explains, “the political and intellectual leaders raised the next generation of leaders” with their speeches (99). Thus, students learned to listen to Horton’s advice in this address like they did in the case of any other literary address.

However unwillingly and unacknowledged, the collegians whose eyes and ears were open to Horton bore witness to Black intellectual production. They learned that they could not dismiss Horton as a “public ignoramus” but instead had to contend with him as a poet. They exchanged knowledge of their intimate, personal lives with him. Only armed with such knowledge could Horton compose his acrostics for the “tip top belles” of the South in the first place. Indeed, familiar intimacy might be the best way to describe his relationship with Caroline Hentz, wife of professor Nicholas Hentz. Mrs. Hentz learned to trust Horton with her expressions of mourning and grief. When she “strove in vain to avert the inevitable tear slow trickling down her ringlet-shaded cheek” as he dictated a poem about her recently deceased child, Hentz gained crucial knowledge about empathy—namely, that it was not bound up in distinctions between enslaved and free (Poetical Works, xviii). Finally, while the students held no claims of ownership over Horton, they nonetheless transformed Horton into their black bard. As Leon Jackson explains in The Business of Letters, students who paid Horton for his acrostics, or gifted him with books and clothing, acted like slave owners in their patronage, which “persisted for years and endured across generations, creating a sense of familial continuity” (60). With Horton, as perhaps with all of those enslaved on Chapel Hill’s campus, students learned lessons in being purportedly generous masters.

Such observations tell us a great deal about the intellectual community Horton was embedded in at the University of North Carolina. It was a community where an enslaved man could learn to write, sell poetry, and confer with students without the threat of punishment. At the same time, it was a community where an enslaved man could relentlessly launch campaigns on behalf of his freedom and nevertheless remain enslaved and exploited by those who (at least in theory) had the power to free him. Ultimately, Horton’s life and labor at the University of North Carolina expands the knowledge of Southern slavery beyond the scope of the plantation. Horton’s story brings slavery to the door of the academy. In doing so, it exposes the way that intellectual labor worked in tandem with physical labor, and both could be—and were often—exploited by institutions of higher learning.

Lesa Redmond is a Ph.D. student in the History Department at Duke University. To read more about her research on the history of slavery and its connections to U.S. colleges and universities, see her contributions to the Princeton and Slavery project here.

Featured Image: George Moses Horton historical marker in Pittsboro, North Carolina. Image courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill.