By Nile Davies

Years before it became the Schomburg Center—a treasured repository for research in Black culture and history—the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library on 135th St was a site of institutional abandonment: an emblem of the neighborhood in which it stood. As Audre Lorde noted in her 1981 interview with Adrienne Rich, its shelves received “the oldest books, in the worst condition.” (722)

It was a place where a librarian like Lorde might observe the material manifestations of neglect as ordinarily as she would in her poems, or as faculty on the SEEK Program at the City College of New York, where she taught alongside Rich, in the campus overlooking St Nicholas Park. Even from the depths of childhood memory, for Lorde, the image of the library is lucid and lingers without explanation: how the brutalized books themselves indexed a wilful indifference at the hands of some anonymous actor, at once unspoken and overt.

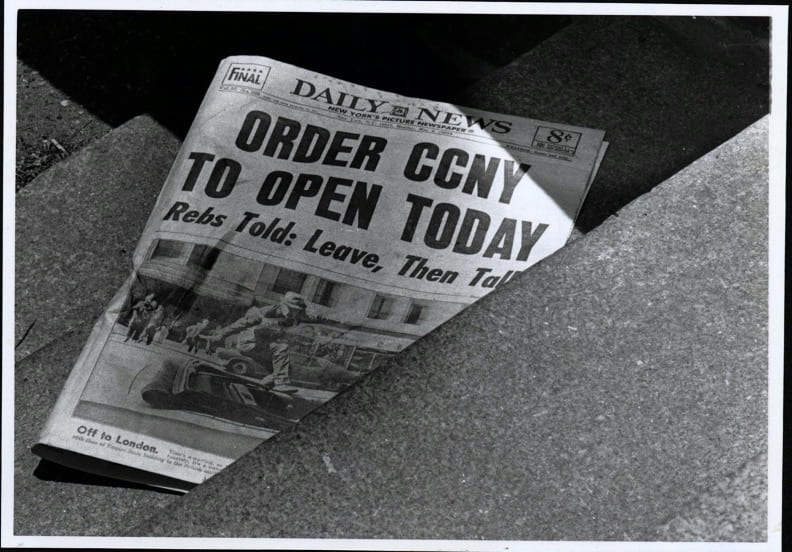

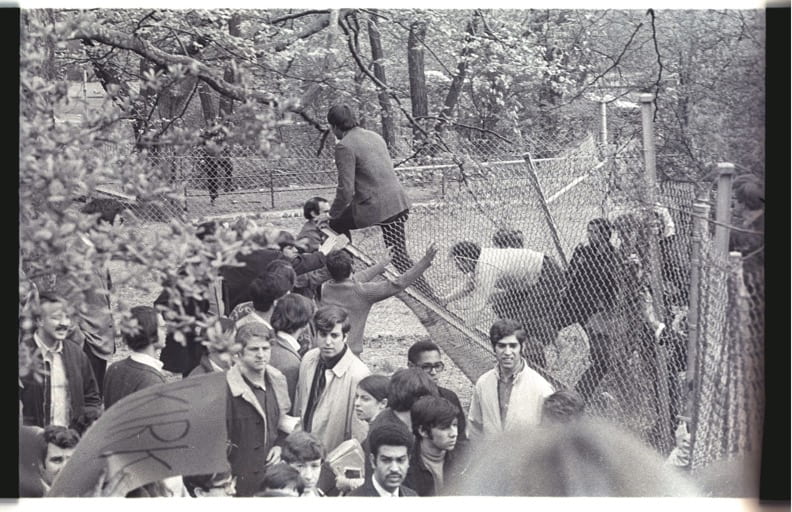

SEEK stood for “Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge.” In the late 1960s, the program would emerge as another kind of emblem, feeding into ongoing struggles for ethnic integration in American public schools and colleges: “a nucleus for counteracting the institutional inequalities entrenched in its admissions, curriculum, value systems, and relationship to the surrounding area.”[1] Under immense pressure from local residents, by 1970 the City of New York was compelled to adopt an open admissions policy for the universities under its administration, transforming what it called its “standards of access” in order to meet political demands for representation and inclusion: desires that the institution should reflect—in some concrete, if inescapably symbolic way—the world outside its walls.[2]

Decades later—after Lorde passed away from cancer in 1992—Rich offered her own reflections on her experiences and the whiteness of institutional life while teaching on the SEEK Program: How her faculties of observation were increasingly enmeshed with those of her interlocutors and students in Harlem. And how, in Harlem, the same forms of neglect that manifested themselves in the city’s libraries and schools could be sensed in the lives of those who passed through them, and whose embattled presences revealed their nature to Rich, as teacher turned student:

Walking up to Convent Avenue from Broadway, and in the classroom, I saw much that became part of my own education, having to do with the daily struggle of poor African-Americans and Puerto Ricans to live and, if possible, to love and, where possible, to put love into action.

“Somewhere in that time”, she recalls, June Jordan had written the poem “In Loving Memory of Michael Angelo Thompson”, a 13-year old boy who was struck by a city bus on March 23, 1973, succumbing to his wounds after staff at the Cumberland Hospital in Fort Greene refused to admit him entry to treat his fractured skull. “He was killed,” writes Jordan:

He did not die.

It was the city took him off […]

Please do not forget.

A tiger does not fall or stumble

broken by an accident.

A tiger does not lose his stride or

clumsy

slip and slide to tragedy

that buzzards feast upon.

Conveyed in Jordan’s verse is the repetitious insistence of a worldview forged by grief and weary cynicism towards the explanatory narratives in which unvalued lives are routinely snuffed out, chalked up as accidents or exceptions. It is the analytical clarity that resists the innocent notion in which certain harms can be attributed to mere mundane misfortune or anomaly. That when indifference is willfully accumulated in the bodies of certain populations, it is indistinguishable from murder.

These words had a particular resonance for me this past summer, when the substance and visibility of race—as event and as deep structure—appeared to ignite in the collective consciousness the sense that what we were witnessing on our screens was related in some concrete way to the elementary dysfunctions of institutional life; dysfunctions which had, up until that point, gone unresolved, if not altogether unnoticed. Racisms writ large in the form of violent spectacle appeared to draw the gaze inwards, seemingly calling attention to the relationship between what was happening “outside” or “in the streets” and the harms of our more immediate surroundings: in offices and boardrooms, galleries, libraries, schools.

Clearly I was not the only one to observe this feeling of structure—the way the parts appeared to represent the whole. At Columbia, the messengers of racial justice spoke to us, offered guidance and support. “RESOURCES FOR PROMOTING RACIAL JUSTICE AND ELIMINATING ANTI-BLACK VIOLENCE” were made available to us, as if, taking it upon ourselves to imbibe the essence of these texts and their ethics, we might all learn to become otherwise—to fashion new and better lifeworlds, producing new structures in their image. Furnished with lists and syllabi, it seemed that the intellectual labors of Black Scholarship—that is, the thinking and writing of those who claim blackness as an authorial identity—as well as those whose work considers race and racism as indivisible from their intellectual projects, had suddenly become essential reading: assigned a talismanic function in the teachable moment.

For those, as Lauren Michele Jackson writes, “already predisposed to read black art zoologically,” the promise of political revival to be found in a familiar litany of anti-racist reference texts suggested the approximation of a Black Canon as the engine of personal transformation. In myriad sociologies of racemaking and the carceral state, redlining and reconstruction, lay the promise of a more perfect union still to come. Making joins and connections, revealing the junctures of our contemporary malaise with our tortured history, one could plausibly read themselves towards a greater understanding of the undergirding structure. This much at least seemed possible, even if not undoubtedly true.

At the same time, it felt difficult to square the intimate activity of reading with the political demands of the world outside. To seek radical transformation in scholarship alone suggested a familiar repertoire of moves to innocence and magical thinking made possible in the claim of having simply not yet read the right books. Even as a means for fugitivity or solace, the world on the page and that which confronted us in the realm of the real were separated by more than their medium. We could commit tropes and statistics to memory, rehearse the logical fallacies that buttress ideologies of oppression: that “mere tolerance”, as Audre Lorde knew, constitutes “the grossest reformism”; or that the long-professed linkages between the personal and political demanded the coalition of disparate movements towards a common struggle. But the path from knowledge to power was long and full of obstacles. What would the effects of that education be? And how would they reveal themselves, so that we might know that the spell—the structure—was unworking itself?

It was the summer of the mission statement, of visions for equity and inclusion: the ubiquity of diversity’s poetics in countless sentimental gestures and displays of solidarity. Studded with hyperlinks, such utterances reflected beguiling examples of the affective labor of diversity in institutional life in its various forms, attuning its environments and agenda to encompass the problem identified. Reading public relations to emerge from this moment offered up an opportunity to turn to such texts as method, in Sara Ahmed’s phrase: “to follow the documents that give diversity a physical and institutional form.” (12) In her book, On Being Included, Ahmed tells a story:

I am speaking of whiteness at a seminar. Someone in the audience says, ‘‘But you are a professor,’’ as if to say when people of color become professors then the whiteness of the world recedes. If only we had the power we are imagined to possess, if only our proximity could be such a force. If only our arrival could be an undoing. I was appointed to teach ‘‘the race course,’’ I reply. I am the only person of color employed on a fulltime permanent basis in the department. I hesitate. It becomes too personal. The argument is too hard to sustain when your body is so exposed, when you feel so noticeable. I stop and do not complete my response.

Oscillating between extremes of embodiment and abstraction, invisibility and surplus, the self-conscious forms in which diversity takes shape in institutions are often self-defeating, revealing deficiencies that might otherwise have gone unannounced in the renewal of vows to do more or begin again, or the remorseful recognition of its history (which might not be the same as feeling contrition.) After all, how can an institution be said to feel? At its heart, an institution is a structure that derives stability from its essential changelessness. Its survival depends on novel modes of self-correction and refashioning: familiar and repeated gestures by which it adapts to absorb and mitigate the appearance of harm. Such poetics—in their symbolic, promotional form—draw attention to the paradoxes of the liberal ideal that seeks to obliterate the very notion of difference as a social reality at the same time that diversity’s utility within the public sphere is valorized as its own ethical good.

At Columbia, the acquisition of new human resources to combat the reproduction of racism was described in an open letter from the Office of the President, underscoring the urgency of its commitments to diversity in a blueprint for concerted administrative reform:

The University will immediately accelerate our program focused on the recruitment, the retention, and the success of Black, Latinx, and other underrepresented faculty members as part of our longstanding and ongoing commitment to faculty diversity. This will include (1) new support for faculty cluster hires in two areas: STEM and scholarship addressing race and racism, (2) the hiring of health sciences faculty whose work focuses on the reduction of health care disparities in communities of color, and (3) University-wide recognition for faculty service in support of diversity and inclusion.

What would it mean if such strategies were understood first and foremost as an admission of institutional malfunction, rather than simply as evidence of a commitment to a process of repair that is always already ongoing? In the form of public relations which seeks to make an institution’s transparency visible, signs and speech acts that appear to herald ethical virtues can obscure as much as they purport to let light in, signifying the very harms they claim to remedy. To be assigned a pedagogical role in the wake of social rupture underscores the intrinsic claim and fallacy that strategies for representation threaten to conceal: that the diverse body––on account of its very essence––fulfils a therapeutic function in the institution’s plans for longevity. In the lexicon that imagines an institution through a set of spatial referents (margins, centers, gatekeepers, floodgates), it is as if the proximity of othered presences intensifies the demand for the reorganization of these structures, rushing in to fill the gaps their alterity has levered open.

This is certainly one way of breaking and entering into the institution, even as it calls attention to the elusive “privilege” of the universal––the blank, genderless citizen, unburdened by its body––and the hierarchies of differential personhood that undergird such cloistered spaces. Such an understanding might also hint at the conditions on which the fractious presence of those othered bodies is established: the degree to which their presence is so often made synonymous with “complaints” to overhaul institutional structures and the roles that they have prepared for us.

How might we come to terms with the ambivalent promise of such “liberation” when the cost of being overdetermined from outside (to borrow Fanon’s phrase) is to always stand for something else, for something other than oneself. As Jordan put it in her book, Civil Wars:

My life seems to be an increasing revelation of the intimate face of universal struggle. You begin with your family and the kids on the block, and next you open your eyes to what you call your people, and that leads you into land reform into Black English into Angola leads you back to your own bed where you lie by yourself, wondering if you deserve to be peaceful, or trusted or desired or left to the freedom of your own unfaltering heart. And the scale shrinks to the size of a skull: your own interior cage.

Encompassing extremes of perspective and scale, to speak of the structure as a real and present force in the shaping of an individual life is to acknowledge the impossibility of one’s insulation from the ethical demands of political life: the ever expanding claims by which one is fixed and called on by others. Indeed, one’s freedom might well depend on one’s capacity, or willingness, to navigate those structures and one’s position within them. To write about the worlds we occupy, however provisionally, holds out the promise of illumination in texts and the worlds they render beyond their margins, gesturing towards the structures of institutions and their own, often deeply intimate, politics.

[1] Conor Tomás Reed, Lost & Found: the CUNY Poetics Document Initiative. Series 4, Number 3, Part 2.

[2] In 1969, the composition of CUNY undergraduates was 14.8% black, 4% Puerto Rican, and 77.4% white. By 1974, 25.6% of CUNY students were black, 7.4% were Puerto Rican, 55.7% were white, and 11.3% were members of other racial or ethnic groups.

Nile Davies is a doctoral candidate in Anthropology and the Institute for Comparative Literature and Society at Columbia University. His dissertation examines the politics and sentiments of reconstruction and the aftermaths of “disaster” in postwar Sierra Leone.

Featured Image: The New York Public Library’s 135th Street branch, c. 1930. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.