Pannill Camp is Associate Professor and Chair of the Performing Arts Department at the Washington University of St. Louis. He has written on French theatre and dramaturgy in the eighteenth century, and he is currently at work on projects focusing on performance and freemasonry in eighteenth-century France and on the long history of theatrical ideas and social theory. He is interviewed by contributing editor Max Norman about his article, “The Theatre of Moral Sentiments: Neoclassical Dramaturgy and Adam Smith’s Impartial Spectator” that appeared in the most recent issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas (October, 81.4).

Max Norman (MN): In “The Theatre of Moral Sentiments,” you argue that Adam Smith drew on French neoclassical theories of drama in theorizing his figure of the impartial spectator in the Theory of Moral Sentiments. How can we be sure that he was using a theatrical metaphor, and not merely interested in a more generic third-person perspective on first-personal experience?

Pannill Camp (PC): Scholars working on Smith have taken widely different positions on this question. As you might expect, scholars with a literary bent, but also philosophers such as Charles Griswold, have interpreted Smith’s spectator as a sign of a deeply embedded theatrical metaphor. But D. D. Raphael rejects this outright, arguing that Smith would have used the language of “actors” more than he did if the metaphor were intended. Raphael is right that there’s scant hard evidence that Smith overtly relied on a theatrical metaphor, but what is clear is that spectator terminology infiltrated British moral philosophy from Shaftesbury on, and its source was most likely the morally inflected theatre criticism that proliferated in the first decades of the eighteenth century. Polemics concerning the morality of the stage by Jeremy Collier and others produced abundant critical and moral discourse. Strands of that were picked up by Richard Steele and Joseph Addison. You can see in eighteenth-century moral philosophy that the term spectator comes to serve a more or less technical purpose, signifying precisely a third-person morally-attuned perspective, but there’s no reason to believe that the freight of theatre association has been stripped away. When Smith and Hume privately debate finer points of the Theory of Moral Sentiments, they invoke problems in dramatic theory. So I think that in fact, the concepts of dramatic criticism were part of the foundation of British moral thought.

MN: How does the specifically French intellectual genealogy you trace change the way we read the Theory of Moral Sentiments?

PC: There are unique features of French neoclassical dramatic literature. Adam Smith was a proud partisan of French model, and not a fan of Shakespeare. Besides the familiar “unities” of time, space, and action, French playwrights and critics were invested in the convention of rigorously separating stage action from the world of facts. It was important to prevent the audience from losing track of the boundary between the bounded truth of the theatrical representation, and the greater world in which the people you are watching are actors. So for example in the plays Smith admired most, you could not have a soliloquy, because it could be taken for direct address to the audience, and trouble the ontological barrier between the two worlds. This concern with not blending fact and fiction had implications for the way Smith understood sympathy, and impartiality. Smith’s understanding of sympathy (in which we imaginatively project ourselves into the circumstances of others, rather than partaking somehow of direct communion with their feelings) is distinct in part because it does not rely on the real existence of the feelings of others. Just as we can sympathize with someone who is unaware of their pitiable state (Smith cites the insane and the dead as examples), we can feel intense sympathy with actors, who may or may not really feel anything. We can sympathize with entities that don’t exist. And regarding impartiality, Smith repeatedly formulates that relationship as that of having no particular connection with someone. Theatrical representation is an ideal, common sense example of this. My moral feelings about Phedre, for instance, cannot be tilted by my relationship to her. This was precisely the reason why Smith’s French contemporaries, including Diderot, thought that the theatre provided moral education. Even people who were corrupt and unjust in life were thought to get their moral bearings when watching a play, because they couldn’t be influenced by any selfish or indirect interests.

MN: Does it have implications for Smith’s economic theory in the Wealth of Nations?

PC: I believe so. In the Theory of Moral Sentiments Smith suggests that a felicitous moral order can arise from impersonal dealings with others. If my ability to sympathize with you doesn’t rely upon my knowing your inward state, or knowing you or your circumstances intimately, and if my ability to be impartial toward you is in fact bolstered by my ability to regard you as if I had no particular connection to you, then a spontaneous moral order is possible for even a very large society where members don’t all know each other. This is true, critically, because I also need to be able to represent an impartial view of my own conduct in order to guide my own actions, rather than relying upon what others may actually tell me. There’s a long tradition of understanding Smith’s moral thought and his political economy as opposed, if complementary–one concerned with benevolence and the other with self-interest. To the extent that we understand Smith to think that the French ontological boundary between actors and spectators can be applied to real life, as the ideal version of what happens when we engage in social action regarding multitudes of people who we can’t know personally, we can interpret that specific influence upon Smith as an element of his faith in impersonal dealings in general.

MN: As you remind us, Dryden famously believed that theater could provide moral education to its viewers. To what extent does Smith view the act of moral spectatorship as educative or edifying? For Smith, does moral spectatorship merely inform our actions, or does it also work on our moral sensibility?

PC: This is a good question, because it requires us to imagine what Smith would have written about theatre-going itself. There are abundant theatrical citations in the Theory, but they are almost always used as examples of the more general principle he is trying to illustrate about a sort of moral action, and specifically how the mechanics of sympathy operate in that sort of case. So for example he claims that dramatic examples prove that we feel stronger sympathy with emotional suffering than with physical pain. He is concerned with the spontaneous coordination of sentiments based on fundamentally inborn tendencies in human beings, or what arises in social life in general, so we have to guess what he might say about the educational benefits of theatre. But I believe he would say that theatre provides moral education, and not just because the French dramatists like Diderot and Louis-Sébastien Mercier, with whom he agreed on other points, did. Smith claims that if we have had a particular experience, like falling in love, we are more disposed to sympathize with others when we observe them having that experience. This suggests that our moral dispositions are malleable. Furthermore, he believes that we feel intense pleasure when we sympathize with others–even when we sympathize with painful emotions, such as grief. On this basis I would imagine that he would expect that when we are surrounded by an audience feeling benevolent feelings toward a stage protagonist, that we are naturally inclined to indulge in those same feelings. And because Smith believed that we need to engage in a complicated imaginative exercise, summoning the “impartial spectator” to view our own conduct, it makes sense that direct experience with the perfectly impartial perspective the theatre supports would habituate us to seeing real actions in the same way.

Max Norman studied comparative literature and classics in America and England, and now writes often on art and literature for magazines in both countries.

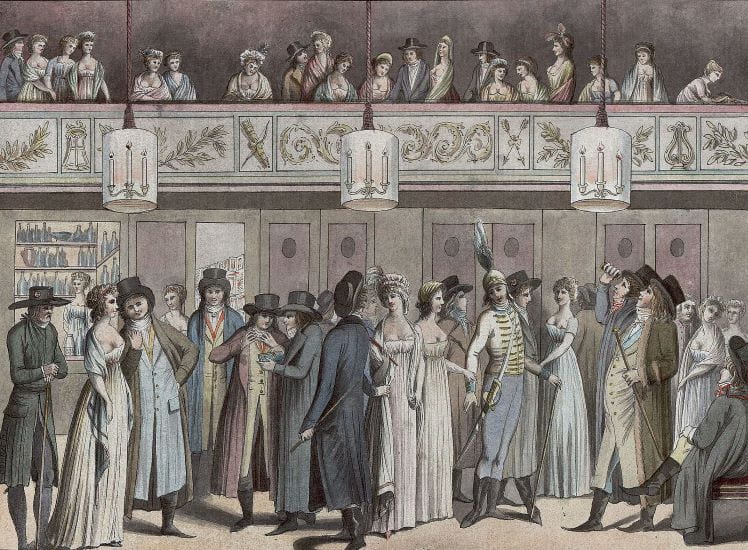

Featured Image: Louis Binet, Foyer du Théâtre Montansier au Palais-Royal. 18th Century. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

1 Pingback