“Whoever you value, you exhibit. You can tell who institutions value by what they display”

By Nuala P. Caomhánach and Rashad Bell

On September 9th 2020, five experts discussed botanical museums in the virtual workshop Decolonizing Living Collections sponsored by Science Museum Fridays at New York University (NYU). The interdisciplinary conversation included DePrator, educator, biophiliac, New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) volunteer; Wambui Ippolito, founder of the BIPOC Horticultural Working Group; Rashad Bell, Special Collections Librarian at the LuEsther T. Mertz Library (NYBG); Laura Briscoe, Collections Manager at the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium (NYBG), and Nuala Caomhánach, Ph.D. candidate in the History Department at NYU and visiting scientist at the American Museum of Natural History The following essay was written after the event because the Science Museum Fridays program, organized by Professor Elaine Ayers of the NYU Museum Studies Program, is a safe space for discussion, and thus, not recorded. The questions asked during the session were sent to the participants post-event to answer.

This is the second part of a two-part conversation.

Read the first part of this conversation here.

Part II Black Botany: The Nature of Black Experience

In February 2020 Black Botany: The Nature of Black Experience exhibition opened at the The LuEsther T. Mertz Library in the New York Botanical Garden to celebrate Black History Month. The exhibition opened a pathway to discuss how to decolonize botanical collections and specialist libraries and at the same time to challenge who was considered an “expert” on making knowledge and meaning. The virtual workshop emerged from the launch and reception of this exhibition. Rashad Bell and Nuala Caomhánach co-curated the Black Botany exhibition.

Ayers: Can you explain the genesis of the Black Botany: The Nature of Black Experience exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden? How did this installation come about and under what circumstances? Why did the exhibit feel important to you at the time that it did?

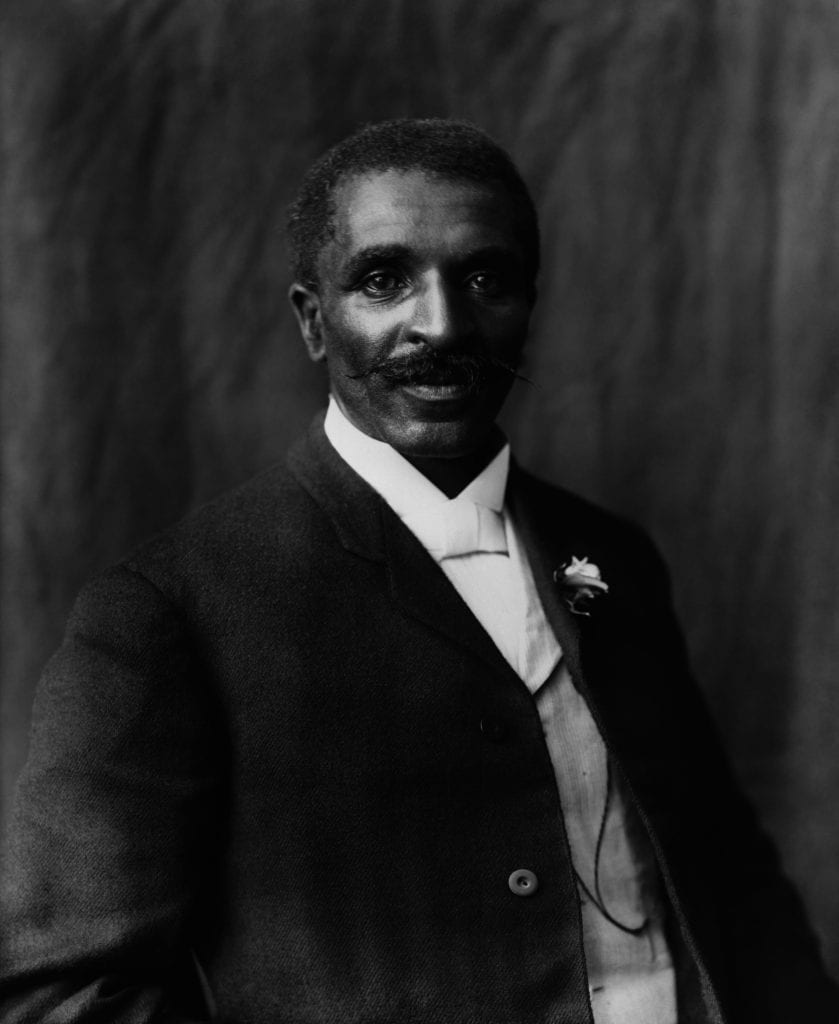

Bell: The exhibit came about when I encountered Nuala in the library stacks researching ebony trees. If you search “ebony” in the Mertz online catalog the first result you will see is George Washington Carver: God’s ebony scientist by Basil Miller. Last I checked ebony isn’t a great way to refer to a black person. While the book is from 1943 and obviously uses antiquated language, this caused me to wonder aloud if the garden was doing anything for Black History Month. I expressed to Nuala that Black History Month didn’t seem like as big a deal as it used to be when I was younger, and I was curious as to her perspective as an immigrant. The conversation continued with Nuala suggesting that we put something together.

Caomhánach: My research focuses on the concept, meaning, and construction of biological time and space across three bodies of scientific knowledge—ecological, Malagasy, and phylogenetic– as applied to conservation ideology and policy from the late nineteenth century to present day. That day in the stacks I was aiming to locate sources about the last stand of Ebony Trees (Diospyros) in Madagascar. Although knowing that behind the search engine is some “object” algorithm, it did seem absurd that the first entry was a Black scientist.

Chatting with Rashad about the ease at which one can dismiss a book such as God’s Ebony Scientist because it was written in a time “where we (white people) did not know any better” not only erased the experience of BIPOC but also enabled a lack of accountability for such racist ideology. We skimmed through the book and it became clear that the author’s take on Carver was that he was a bit odd (“queer”). Whether this is actually a true fact or not, what was apparent was the lack of context about Carver being a Black Man in late nineteenth century American society, and as a scientist within an all-white intellectual community he could not and never free from racism. Carver fascinated Rashad and I because of how different political and activist groups used him as a token for their own cause–it seemed the equivalent of stating today that “I have a black friend” to assert being anti-racist. The author’s tone-deafness was only matched by the NYBG’s lack of programming for Black History Month. As an academic (and then NYBG Mellon Fellow), I was allowed immense latitude to challenge this position as scholars carry a form of “freedom” to speak up. As a scholar who wishes to elevate Malagasy knowledge systems, it felt hypocritical to not use my privilege to elevate the voices of those who could not. Rashad and I hatched some plans, and I went to talk to Vanessa Sellers, Director of the Humanities Institute. Vanessa said “let’s do it” and jumped in to get the wheels turning. It was a magical moment.

Ayers: Conceiving of an exhibit is one thing, but receiving support for it is another, and I understand that you faced some major institutional challenges in bringing Black Botany before the public. Could you speak in more detail about the obstacles that you encountered in working on this exhibit? Where did you receive push-back, and from whom?

Bell: I was initially hesitant when Nuala suggested that we do something for Black History Month because in these situations I know what the response will be; a myriad of excuses disguised as reasons “we already have something planned for February (Ferns in this case), you have other work to do, exhibits are someone else’s responsibility, etc.” followed by “write a proposal”. Working in an academic space where I am the only black person on the library staff and at the bottom in terms of organizational hierarchy, and understanding that unconscious bias does play a role in decision making, I didn’t have high expectations that anything would come from my suggestion. I’ve been in enough situations in my career to anticipate the answer being some form of a polite but firm “no”. Sympathetic to my reluctance, Nuala offered to present the idea to the staff, which, to my surprise was met with enthusiasm. The library staff is an amazing team and we all worked together to put this exhibit together within a limited amount of time. This is the part of the story where I will point out that my past negative experiences combined with my own internal biases caused me to expect the worst. My informed decision would have been to do nothing and go about my business and we would all be the lesser for it.

When Vanessa gave our project a huge thumbs up, our next step was deciding what stories to tell. Rashad and I wanted to “go fresh” with creative stories about BIPOC, however, in an institution such as NYBG –a space that had yet to acknowledge the legacy of colonialism– we made a mindful decision to start there. We wished to explore how plants are not passive actors in the making of history, a mere backdrop for the drama of the natural and human world, but can shape key societal systems—such as labour. For example, cotton (Gossypium) stood at the center of the most exploitative and violent production complex in human history: slavery. The cotton plant was grown in very tight rows and the bolls ripen from the lower to the upper stems. Thus, enslavers managing plantations thought Black women and children offered the best means to maximize harvesting output. We wished to present a thought-provoking exhibition that acknowledged the limits of the archive while bringing materials together in a way that carefully and creatively invites the visitor to see and think beyond those limits . Sources about African people and people of African descent often are incomplete, steeped in colonial bias against all people of African descent, as well as heterosexist biases against women across race. Thus, we had to be mindful of how we framed these stories, especially for Black women who are almost wholly erased from the archive.

The Mellon and Mertz staff were incredible—everyone bringing their skills to the production of this exhibition. Rashad and I wrote as if no-one was looking using all the “taboo” words (white-washing, rape, colonialism) as we figured the push-back would come from the way we framed this exhibition within these terms. To our utter delight, the Vice President of the Mertz Library, Susan Frazer, and Vanessa Sellers corrected our grammatical mistakes, but they omitted nothing of the content. Here were two white women in leadership positions opening the door that was otherwise locked for good. It was humbling. The obstacles we expected (outright rejection, appropriation of ideas, and office politics) did not occur in the production of this exhibition. That experience was waiting for us in the summer when the NYBG “uppers” wished for us to curate a 12-month long online exhibition.

Ayers: Like all other institutions, the NYBG shut its doors during the onset of COVID-19 soon after you installed the exhibit in the library. How did the pandemic affect and/or complicate your planning for Black Botany?

Rashad: Due to the overwhelming positive response to Black Botany we had received approval to keep the exhibit up through the end of March. Two weeks into the month, NYBG shut down. We were hoping to have additional programming along with the exhibit throughout March such as educational activities for children and community discussions.

Caomhánach: Honestly, it was so disconcerting as the exhibition was gaining visitor engagement inside and outside of NYBG. Rashad and I were giving tours to staff and volunteers from other departments at NYBG which was pretty amazing–the feedback we received from staff and interns of all ages merely reinforced the need for this kind of approach to exhibitions within cultural museums. Currently the NYBG is posting one plant a month from the exhibition on the NYBG Instagram page to highlight the online exhibition.

Ayers: How did your own identity play into your experiences in curating this exhibit—both in feeling the need to bring it before the public, and in the complicated way in which this exhibit unfolded over the spring and summer?

Rashad: As I stated above, Black History Month didn’t seem as big a deal as it was in my youth. As an adult I feel like I’ve had to seek out more content and events. Growing up in a predominantly black community in a city that was pretty much 50/50 black and white, Black History Month always felt like a big thing in my youth. So, when we were bringing the exhibit to the public the underlying idea was to not just respectfully communicate these stories and ideas but to help people understand that these stories are important parts of our society and worth being known all year round, not just in February. These are segments of history from our society. Developments and choices that influence our way of life to this day.

There is also the strange pressure of being a singular person in the position of representing an entire race of people. No race is monolithic and no one person can be everything.

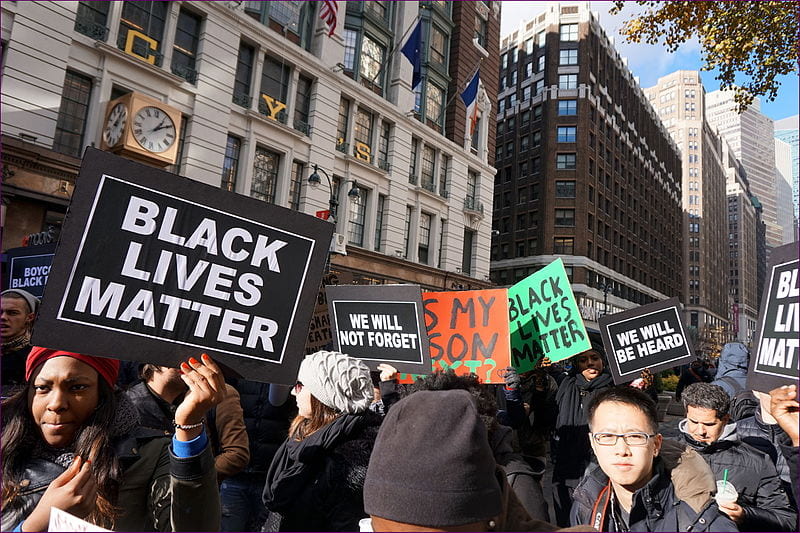

As for the way the exhibit unfolded over the spring and summer… The cultural developments of the BLM protests combined with the pandemic just highlighted the importance of this exhibit and why we need to have these types of conversations. I was cautiously excited when I was presented with the opportunity to expand the exhibit. While I unfortunately cannot speak on what occurred, I will say that it took a very heavy emotional toll on me. I am incredibly grateful to my collaborators who noticed that I had been out of contact and reached out to check on me, they truly helped me fight my way back from the brink.

I will stress to others, when working on exhibits like this to really think about why. Are you participating in a cultural zeitgeist? Is this something you actually care about? Are you doing it so that you can say you did or do you really want to share this information with a wider audience?

Caomhánach: Without a doubt my identity played out in shaping this exhibition. First, I have lived in the United States for many years and have an Irish brogue. In many ways this enables me to get away with things others may not be able to—some call it “charm”. I think it’s a distraction that allows me to get up to good mischief, such as this exhibition. Second, after many years living in the United States, it became apparent how much was stacked in my favor. I am an immigrant, but not “that kind of immigrant” as I am white, Irish, educated, and people assume I am middle class. I believed that working together to produce the best exhibition possible meant being open to all advice and utilizing everyone’s skills. Interdisciplinary collaboration is a must; this exhibition would not have been possible without the generous support and guidance from the library and herbarium staff. This interdisciplinary model in exhibition production was the mindset Rashad and I had when we were asked to develop a 12-month long online exhibition. Our excitement to include those traditionally excluded from exhibition development, for example, homemakers or high school students from the Bronx, was in part a desire to challenge the institutional category of “the expert”, i.e. those with higher degrees. The expanded exhibition was rejected and I am unable to say much more than that. The Irish have a reputation for being feisty and fighters, and over the summer I leaned into this stereotype. I learned so much over the summer about how many white people wish to seem “woke” or make the black experience a product, but truly do not wish to do the mindful, conscious, inclusive work to elevate those who cannot get their elbows to the table. As the project came to a close, to see the impact on Rashad was so deeply upsetting. We were trying to be inclusive and transparent, and aiming to produce a fresh and rich exhibition to honor and explore the experiences of black men, women and children from the colonial period to today, however, I stood powerless as a witness to institutional gaslighting and badly disguised racism. I think about that a lot, what could I have done differently, what will I do next time this happens, because it will.

Ayers: As a botanist, how have you navigated working between the sciences and humanities to construct fuller, richer stories about the specimens you study? What value and challenges do you see in working across disciplines (or even across collections within the same institution) in constructing these stories?

Briscoe: I feel like museum collections managers have so much in common with librarians and archivists, and yet we are doing similar work without the same kind of formal education in materials and methods. Similarly, my education was in biology, not history or sociology. So trying to tease apart these questions of the human element is of great interest to me, but I don’t have the same tools as colleagues in other disciplines. Which is a disservice to everyone, to try to address issues one is not really equipped to address. And I think it can feel very overwhelming, to have a desire to ‘decolonize’ collections but have no real clue what that looks like or even what questions to start with. But I’m very grateful for forging these new connections across disciplines to be able to better ask questions, find new ways of doing things, and move forward.

Ayers: One of the ways you’ve told deeper stories about the specimens you study has been through the NYBG’s Hand Lens series. Could you tell us more about the Hand Lens, how you’ve approached it, and what’s happening with it now?

Briscoe: The Hand Lens is a public outreach extension of the C.V.Starr Virtual Herbarium. We wanted a way to connect with the public, people from all walks of life, to tell stories about plants and fungi. Every collection has a story. Maybe it’s a story about the species collected, or maybe it’s a story of the person who collected it, or the time and space in which it was collected. We knew from our experience doing open houses and other outreach events, that these kinds of stories are very well received. In the midst of climate change and a biodiversity extinction crisis, people crave authentic connections to the natural world. To me, a venue like The Hand Lens is also a perfect opportunity to share stories previously untold. Plants usually don’t have the limelight afforded to more charismatic vertebrates. But also, whose stories are we telling? I think all museum holdings now have a very clear opportunity to shift their lens, so to speak, away from the white, often male, dominant perspective. What do we know about women who were collecting plants? What stories can we tell about indigenous plant use? Or the many and varied roles plants have played in the African Diaspora? We were so excited to help Mertz Library staff format their Black Botany material for supplemental posts on The Hand Lens, using herbarium specimens to help illustrate their stories. I think for museum collections, there’s a great opportunity and responsibility to take to broaden the lens of which stories are told and to center non-dominant stories whenever possible.

PART III The Limits of Being in the Institution

Ayers: Can you explain the background of the “folders project?” How have folders been used in herbaria to construct, even unintentionally, narratives about geography that appear to be linked to racist categories of humans?

Briscoe: It’s very common for natural history collections to use color coding for geographic regions, so staff and researchers can see at a glance if the cabinet contains material from the regions they’re looking for. In the herbarium this means a map with color coded continents/regions and also physical folders of corresponding colors that store specimens from these regions. But there are really no standards. It could be broken down by states or countries. It could be by continent, or by ecoregions. And no two institutions seem to use the exact same geographic groups or colors. The color scheme used for different continents in the Steere Herbarium was put in place in the mid-twentieth century and used colors that corresponded to racial categories introduced by European scientists in the nineteenth century: Yellow for northern China and Japan, red for India and brown for Africa. The resulting map, featured on every floor of the collections area, was an uncomfortable reminder of racism that was dismissed with humor, but in fact made the Herbarium a hostile work environment. A reminder of categorizations of different parts of the world as “other”, through the lens of historical white supremacy. This was a problem that we inherited, the current staff is not responsible! This is an issue in museum culture more broadly – what can we be held responsible for when so many of the issues predate us? How do we grapple with the legacy and move forward? Something that was clearly offensive was never the top priority to replace, in large part because the privilege of a majority-white staff enabled us to be shielded from confronting the reality that it created a hostile work environment in spite of having recognized it as offensive.

Ayers: What are the practical challenges to changing a system like these colored folders at such large institutions? How did a call for replacing these folders come about?

Briscoe: For the folders project, moving forward comes at a literal cost. It is relatively easy to figure out new colors for a map, to vet those colors against people in our community from different ethnic backgrounds to make sure there are no negative associations. But the cost of tens of thousands of folders is not trivial, nor is replacing that many folders part of the normal operating budget for materials or person-time.

Ayers: You also live in the Bronx. How do you feel that the NYBG has interacted with (or not interacted with) the communities and neighborhood around it? Others have mentioned that the garden has a reputation for being “gated off” from the rest of the Bronx. How do you see that playing out, and/or where has the garden been successful in its collaborations with your neighborhood?

DePrator: Living in the Bronx is a unique experience because of the topography. The most expensive areas are located on the highest elevation. The Valley is literally one. Most essential workers reside in these areas and adjacent areas surrounding the Garden. The idea of “gated off” is literal. Just outside the gated 250 acre jewel are the people who enter on “free day.” A nice gesture recently given to Bronx residents is a “Pass” for ground visits for a year. YEAH! This will allow for more exposure to the changing gardens, the enjoyable experiences, socially and emotionally for entire families, especially during these stressful times. Exposing this opportunity is critical to “opening the gates”. That may be underway. The Garden just reopened. So, I’m hopeful that families will appear more frequently. The Bronx is huge and consists of many distinct neighborhoods. Reaching out to find out what would interest them is essential for regular and special programming. People make a special effort to attend events that reflect their interests and significant heritage strengths.

Ayers: What exhibits, displays, labeling, and public programming have you seen at the NYBG that have been particularly successful in engaging the public? Are there other examples that have fallen flat?

DePrator: NYBG is successful in presenting shows that stimulate interest in some people, some of the time. The deeper the specific cultural focus, probably the greater the success. Visible attendance is a true gage. I believe every exhibit chosen is consciously done to attract a specific audience. European artists have been most displayed during my time there. The attendees are as well. The basic foundation of NYBG is designed around European ideals, architecture, and concepts of beauty. A shift to more conscious and inclusive acknowledgement of the surrounding communities of color will be recognized when the community of artists representing the African Diaspora are also exhibited within the spaces of NYBG. You are what you Do.

Ayers: Another theme that has emerged during this panel has been, on the other hand, a deep commitment to working within our fields—history, botany, library science, horticulture, teaching—and a real love for the institutions within which we work. (As Laura mentioned, we wouldn’t be doing this work if we didn’t love the botanical garden and want it to be better.) Could you speak to these dual drives and tell us why you still do the work that you do, given everything that we’ve been discussing today?

Briscoe: It seems clear that we are at a really interesting place with museums right now, in response both to the Black Lives Matter protests of the 2020 summer as well as the financial constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of the historic legacies of settler colonialism in museums (both exhibits and collections) have been laid bare at the exact same time that the future is very uncertain for many institutions. I feel humbled to be working in collections, and feel a deep drive and responsibility to leave things better than I found them. We know now more than we did a year ago, ten years ago, decades ago.

Bell: I often joke with colleagues that we made the mistake of pursuing careers in fields that we are actually passionate about rather than what would make us money. That’s the long and short of it. When you genuinely care about what you’re doing, it’s hard to stop. Even when the world makes it difficult. For me personally, when someone expresses joy at seeing stories such as those in Black Botany, or thanks me for aiding and encouraging them in their research, or when I did public library work (helping people find jobs or a place to live): that is what I consider success. The frustration comes from knowing that I could do better work if I wasn’t worried about feeding myself and paying bills. If the institutions valued things as they claim they do, they would pay the people who do the work and it would benefit them greatly.

Ayers: Can you talk in more detail about the ways in which support has been extended within the group that you felt was missing and, perhaps, unobtainable, at major institutions within which you’ve worked?

Ippolito: It is important to work outside the Academy because we are able to have conversations that we cannot within dominant institutions whose modus operandi has been exclusionary historically. Because we are small, and more importantly because these speakers come from our communities, they are happy to share with us, have us listen to them, and make professional connections. Additionally, because we are people of color, we all understand the trials of working in exclusionary structures. We relate immediately to one another’s issues – if they arise. Members are able to voice how they feel without fear of professional repercussions. We also are working to be able to ensure professional growth for our members outside these structures by connecting with BIPOC professionals based in other countries and locales. Dominant structures operate on a bottom line where profits and conformity are the system. They may in theory be democratic, but are in reality most often exclusionary. We aren’t interested in tearing down those institutions, our focus is on building healthy institutions where all voices and stories are given the same weight. We have worked with one white ally organization and shared our ideas with them.

Ayers: You have recently used social media (especially Instagram) as a way of telling and sharing stories about botany and horticulture that feature African experts, and you’ve connected some of these stories to your own experience as an immigrant to the United States. Could you tell us more about why, and how, you’re using social media to change the narratives that are told about what it means to be a “botanist” and where that work is centralized?

Ippolito: I just tell stories that interest me and I find they resonate with others. Social media is fun for me and I enjoy that others like what I write. All people want to learn something, get a new perspective… It so happens that what I share helps them achieve this. I also learn in the process because I read comments and ask questions, and am led through this, to new insights and information.

Ayers: How do you view community-building within this context? How have you striven to, and seen, community within your institution? How have you formed your own communities outside of these institutions?

Bell: I’ve been lucky enough to encounter people who showed me the value of community building even in oppressive environments. Mostly by taking the time to introduce me to and talk with people at every level. These relationships tend to grow outside of the institutions they were born in.

Briscoe: It is still a challenge to broaden my mostly white network of colleagues. I am so grateful for the internet! It’s such a nice way to seek out and connect to people and groups (like #BlackBotanistsWeek) that would have been much more difficult to find decades ago. I am working to include BIPOC voices in all the projects I’m working on, to get perspective and to help provide opportunities for those voices to be heard.

Ayers: What parting advice would you give to young scholars in your field? What advice would you give to senior staff members at your institutions making decisions that affect your work “on the ground?”

Briscoe: There are so many opportunities for adding context (and value!) to natural history collections, so it’s a really exciting time to be entering the field. Much work is needed to constantly be effectively communicating the basic need for collections, for adequate staffing levels, and for communicating topics that might seem to an institution like difficult topics or topics not in line with their mission statement or public image. I think there’s still some catching up in the museum world to trust that engaging with these topics is not dangerous to institutions, but will earn them even more loyal followers.

Bell: For the younger people: Pursue anything you’re interested in. Don’t limit yourself (others will do that for you), be clever, be honest and genuinely get to know people. Senior staff: See what I said above about actually paying people and get out of the way.

** Title quote was stated by DePrator during the Decolonizing Living Collections Virtual workshop, on September 9th 2020. Permission granted by speaker.

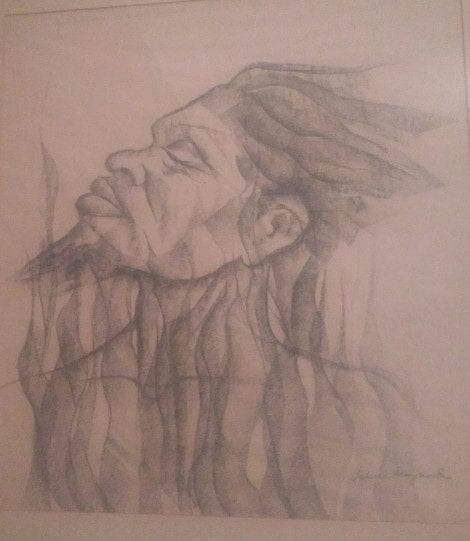

Featured Image: Phoenix Rising by Valeria Maynard. Charcoal, pencil on paper. (courtesy of DePrator).

2 Pingbacks